Hollywood was built on monsters.

In fact, we can thank the popularity of monster movies for the rise of both blockbusters and cinematic universes. But one monster has loomed larger than most, creating the kaiju subgenre and inspiring numerous films and filmmakers in his wake. We’re talking, of course, about King Kong.

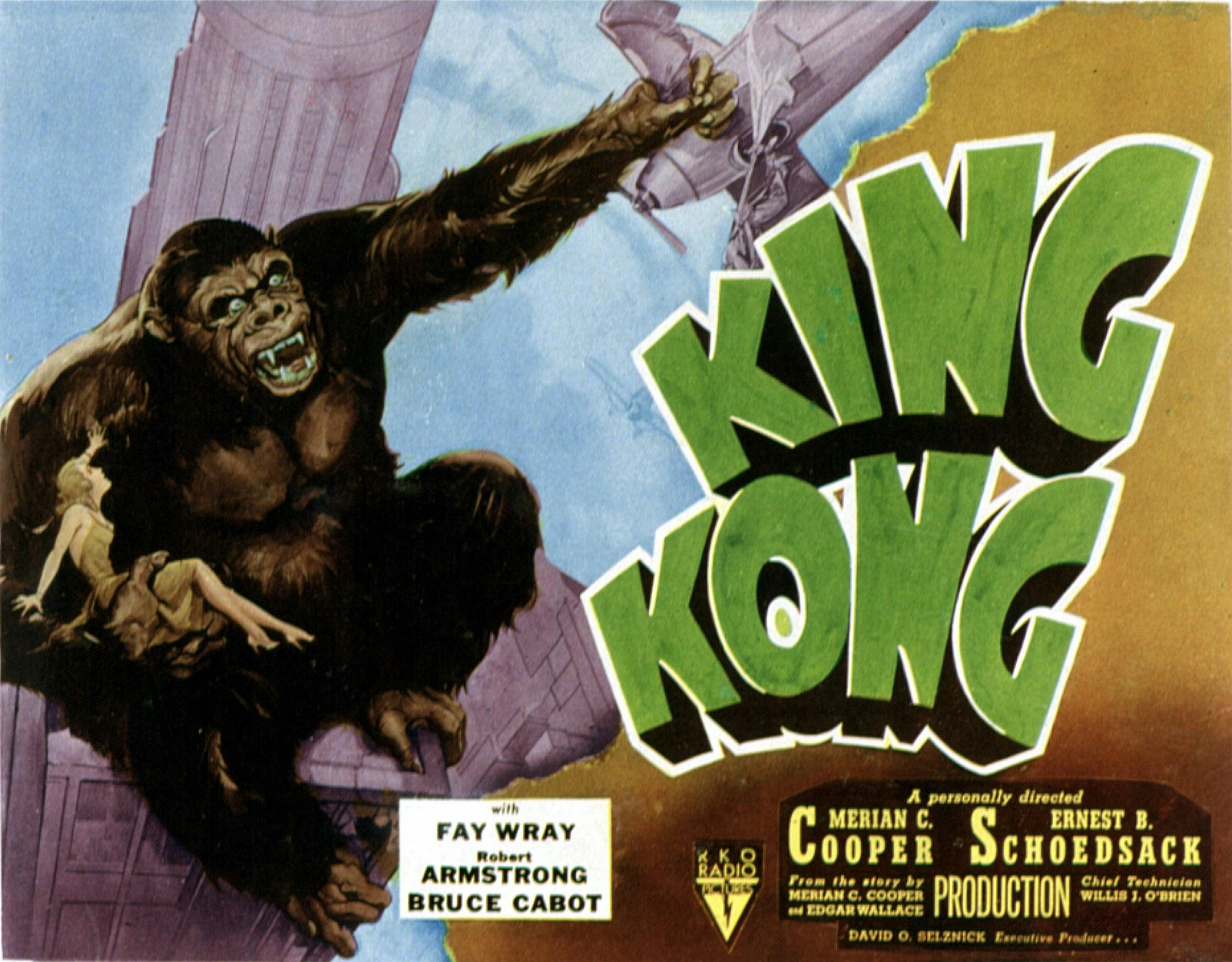

I’ll skip the history lesson, as I’m sure even those who haven’t seen a King Kong film are familiar with the gist of his story: giant ape falls in love with a pretty blonde actress filming a movie on Skull Island. A greedy promoter takes Kong back to the states. Chaos ensues. Buildings are wrecked. A skyscraper is scaled.

So when it came time for Legendary Entertainment to introduce Kong into its nascent MonsterVerse and set up the inevitable showdown against Godzilla, the studio knew it couldn’t just tell the same old story. After several drafts from writers Max Borenstein, John Gatins, Dan Gilroy, and Derek Connolly, something cohesive started to form: the story of Kong before he was King and his first encounter with the outside world, told through the lens of Vietnam.

Kong: Skull Island, directed by Jordan Vogt-Roberts and released on March 10, 2017, follows a group of scientists and soldiers (fresh from Vietnam) tasked by the mysterious agency Monarch to explore an uncharted island — one that happens to be the home of a giant ape, and monsters far worse. The ensemble cast features Tom Hiddleston, Brie Larson, Samuel L. Jackson, John C. Reilly, John Goodman, Tobey Kebbell, Corey Hawkins, Shea Wigham, John Ortiz, Tian Jing, Jason Mitchell, Thomas Mann, Eugene Cordero, and Richard Jenkins.

Skull Island, ironically enough, is the second ape-centric blockbuster to take inspiration from Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now and its textual basis, Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. But where the Planet of the Apes franchise took a darker and more emotionally harrowing route in 2017, Skull Island doesn’t have much on its mind besides having a good time.

Admittedly, Skull Island ranks on the lower end for me in the MonsterVerse franchise, with my preference given to Godzilla (2014) and Godzilla: King of the Monsters (2019) for their more serious character portrayals and the religious depiction of their awe-inspiring monsters. Still, Skull Island has a lot going for it, and it certainly worked for most audiences and critics.

It’s the pulp sensibilities that work in the film’s favor. The choice not to set Skull Island in the present-day gives it the feeling of a ragged 1970s paperback. Cinematographer Larry Fong cements this look, his previous work with Zack Snyder giving weight and believability to the fantastical. A lengthy single shot in which Hiddleston’s gas mask-clad James Conrad cuts through bat-like monsters while poisonous green gas is expelled from beneath the ground is a standout moment.

Hiddleston certainly leans into that pulp approach, playing an adventurous mercenary who eventually embraces his role as a hero. It’s a far cry from his best-known role as Loki, and yet so much of the film’s casting uses the Marvel connection to hook viewers, with Jackson, Larson, and Reilly joining Hiddleston as Marvel cast members. As fun as it is to see all of these actors together in a monster movie, the size of the cast becomes unwieldy. After all, any time John Goodman barely feels like a presence in the film, there’s an issue.

In November 2017, screenwriter Dan Gilroy has revealed that earlier versions of the script featured a more world-weary cast of characters, which makes the appearance of King King all the more powerful.

“She didn't believe in anything,” he told Collider, describing his original vision for Brie Larson’s jaded anti-time photographer. “So the first time she saw Kong, it was like an awakening.”

That lack of world-weariness is my biggest issue with Skull Island. There’s not a single moment where I believe any of these soldiers just got out of Vietnam. They’re all too relaxed, healthy, and optimistic. Compare them to Godzilla’s Brody (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). It’s clear he’s been through hell and left exhausted by the experience. The only Skull Island character who compares is Jackson’s Preston Packard, who gives an Ahab-esque gravitas to his hunt for Kong.

Plenty of people disagree. There’s an entire legion who rank Kong: Skull Island as the best entry in Legendary’s MonsterVerse. And that’s fine. It’s not that Skull Island gets it wrong, it’s just that the approach and tone don’t entirely work for me, particularly as a follow-up to Godzilla.

Where Skull Island works best is the monsters. Vogt-Roberts doesn’t skimp on creating a variety of creatures, citing anime like Princess Mononoke (1997), Spirited Away (2001), Evangelion, and even Pokémon as his inspiration. Whatever complaints I have are significantly eased by the presence of the Spore Mantis, Sker Buffalo, Skrull Crawlers, and, of course, Kong himself. The special effects work is outstanding. Kong’s big battles against a tentacled creature beneath the lake of his territory and later with the Skull Crawlers give the film a rewatchability I can’t resist.

As a thematic piece, Kong Skull: Island doesn’t hit the mark, despite teeing up interesting conversations about conflict, ecology, and religion. But as a giant-monster movie that feels like a kid playing with army men and oversized action figures, Kong: Skull Island is a blast. That is a quality worth celebrating. Because that’s what keeps the monsters alive.