Born in Surrey in 1948 and raised in Glasgow, Iain David McGeachy developed an interest in playing guitar in his teens, aspiring to be just like the “baroque” folk masters of the time, such as Davey Graham or Bert Jansch.

In the mid-‘60s – young, confident and already a capable player – he crammed his life into a guitar case and headed south to make a name for himself on the London scene. Once there, he did so, quite literally, rechristening himself John Martyn upon the advice of his first agent.

His new surname gave a playful nod towards that much coveted American guitar brand – just with a slightly spicier spelling – and he reputedly plucked ‘John’ out of the pool of possible first names because of its everyman connotations.

Not long after, the promising singer-songwriter – already a big personality on the circuit – got snapped up by Island Records and became the first white male solo artist on Chris Blackwell’s largely reggae-focused label.

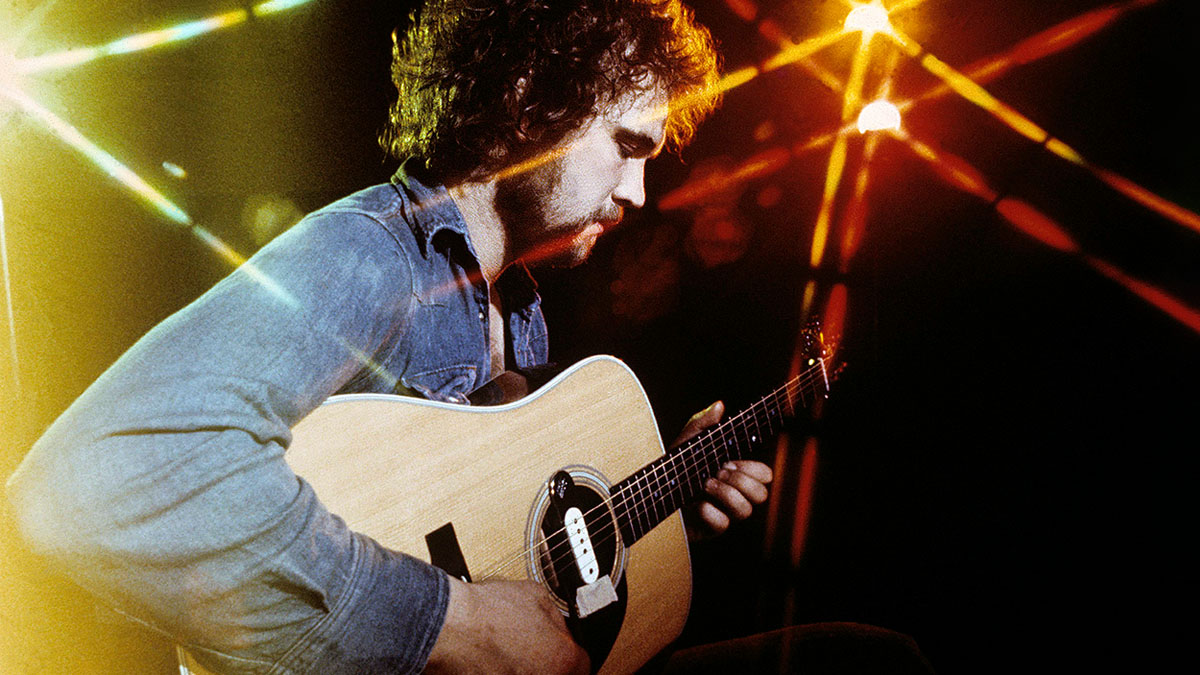

Over the course of 40 years and 23 studio albums, Martyn far outgrew his folk roots, becoming an acoustic guitar innovator who embraced effects designed for electric applications – most notably Maestro’s Echoplex tape delay units – to defy expectations of what a humble acoustic could sound like.

There are also no prizes for guessing which mainstay of his pedalboard got singled out for a special mention, via the medium of double entendre, on Big Muff – a somewhat unlikely 1977 collaboration with eccentric Jamaican dub producer, Lee “Scratch” Perry.

Throughout his career, Martyn also leaned into jazz, blues and world music influences to foster a unique and ever-changing sound.

He even reinvented himself as a suit-wearing, electric guitar playing sophisticate in the 1980s – a move no doubt influenced by the prevailing musical and aesthetic trends of the day, as well as time spent working with Phil Collins on Grace & Danger and Glorious Fool at the front end of the decade.

But no matter the guise, commercial success largely eluded John Martyn. Sadly, it’s quite likely that he earned more in royalties from Eric Clapton’s cover of May You Never than he did from his own stunning original version.

His talents have often been overshadowed by tales of his notorious alcoholism and drug taking antics, partiality for fisticuffs with friends and strangers alike and appalling mistreatment of the women in his life – particularly his first wife Beverley, with whom he’d released two records in 1970 before their relationship soured.

Martyn was a flawed artist if ever there was one. More people may have heard the story of him having his right leg partially amputated to prevent septicaemia - originating from a burst cyst in his knee – from ravishing his entire body than have heard his deep and varied catalogue of music.

In the BBC’s 2004 documentary Johnny Too Bad, Martyn attributed the root cause of this particular ailment to years of uneven weight distribution from playing Gibson Les Pauls, rather than any of his other more toxic lifestyle choices. His doctor may or may not have agreed.

While something of a destructive force upon himself and those who cared to come closest, Martyn’s creative powers on six strings are undeniably fascinating. His influence can be heard in everything from Beth Orton, Bombay Bicycle Club and Ben Howard to Portishead and Massive Attack.

Now, almost a decade and a half since his death, we look back at five ace tunes in the key of John Martyn…

Fairy Tale Lullaby – from London Conversation (1967)

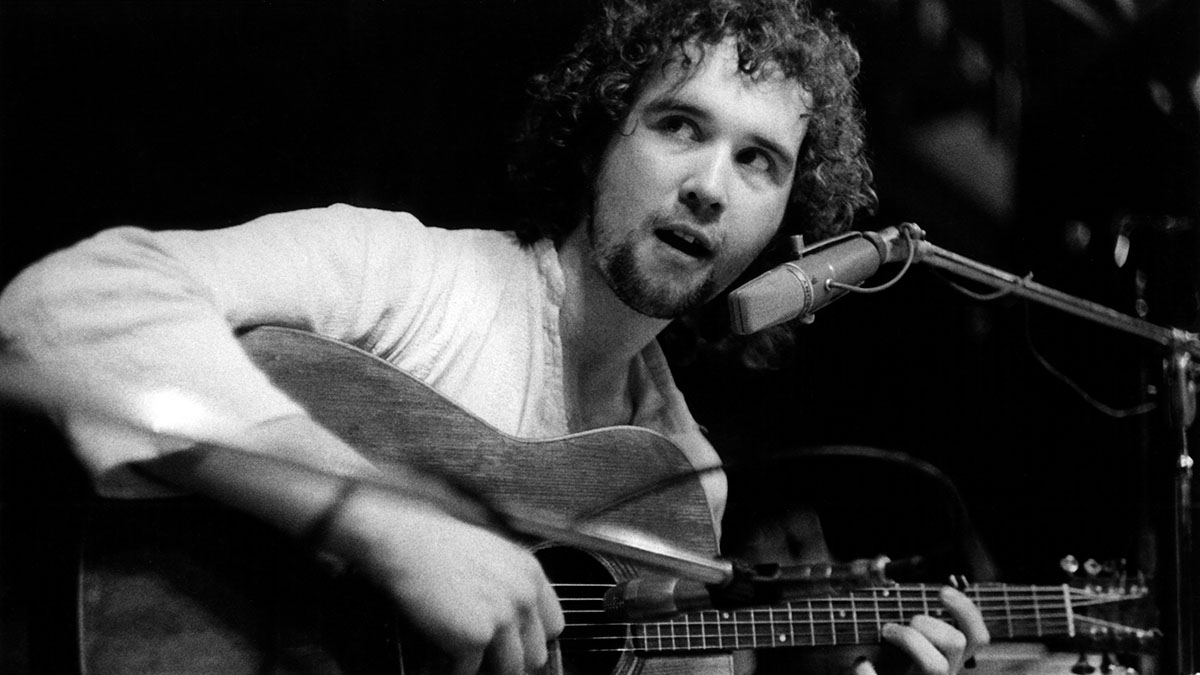

As the opening track of his 1967 debut, Fairy Tale Lullaby was the very first statement John Martyn made to the listening public about who he was as a recording artist.

It's lighthearted, whimsical and uplifting; full of life, optimism and has an endearing level of naivety – both for the wicked ways of the music industry and for life in general. After all, he was just an 18 year-old kid whose dreams appeared to be well on the way to becoming reality when he cut this sweet little ditty.

The whole album, which reportedly cost only £158 to record, is very much set in the folk tradition, with balladic storytelling and no-frills self-accompaniment being the order of the day. An all-acoustic effort, Martyn likely recorded his guitar parts with the same dreadnought he’s seen posing with amid the chimney pots of Chris Blackwell’s West London home on the album’s cover.

Delicate, almost floral hammer-on flourishes give a nod to the folk baroque style that had become popular on the club scene, and the song gets its bright, breezy and decidedly major key sheen from being set in Open D tuning (DADF#AD), with a guitar capo at the fifth fret.

Although rather simplistic compared with the calibre of songwriting and production that was yet to come, the remarkable thing about Fairy Tale Lullaby, and London Conversation at large, is that Martyn had only been playing the guitar for a short while – a matter of months by his own estimation – yet he’d already mastered plenty of the techniques he so admired in others.

With left and right hand autonomy, fluid fingerpicking techniques and an innate sense for melody, rhythm and timing already under his command, the question was: what next?

Hello Train – The Tumbler (1968)

The following year, Martyn released The Tumbler, and his experimental tendencies and some jazzier leanings started to float to the surface for the first time.

Full of drop D drones and the slap of slackened strings, there are sure signs of his signature heavy hitting rhythmic style taking shape on this collection, and four out of the twelve tracks also received an avant garde twist, courtesy of jazz flautist Harold McNair.

Reflecting on the noticeable shift in his sound between London Conversation and The Tumbler in a 1973 interview with Supersnazz 2 fanzine, Martyn explained:

“Well between the two albums I got exposed to London, you see, and at that time all the heroes were about, you know, [Bert] Jansch and Davey Graham, and I just kind of listened a lot to music that I hadn't listened to before, and I met Harold McNair... met loads of people all of a sudden. Between the two I just met all these people that were older and more experienced than me musically. That's the reason for the change.”

Hello Train is a particularly interesting marker of his expanding musical horizons because it makes heavy use of reverse tape effects – AKA playing recorded segments of his guitar backwards – which certainly wasn’t common practice among the folk revivalists and other acoustic troubadours of the time.

Rather, it was a sign of much more experimental things to come and suggested that Martyn had also already begun tapping into the worlds of psychedelic pop and rock for sonic inspiration.

At the time, notable uses of reverse guitar had been made mainly by Jimi Hendrix on Castles Made of Sand (1967), by The Beatles on I’m Only Sleeping (1966) and by The Byrds on Thoughts and Words (1967).

Glistening Glyndebourne – Bless The Weather (1971)

After his first two solo records, Martyn met and married Beverley Kutner and the couple made a pair of albums together in 1970.

Commercially, neither Stormbringer! nor The Road To Ruin made much of a splash, but the recording sessions taught Martyn some valuable lessons in how to interact with a band, and acquainted him with double bassist Danny Thompson (of Pentangle), who would remain a key figure in Martyn’s life and music for many years.

When, at the behest of his label, he returned to his solo career in 1971 with Bless The Weather, Martyn’s outlook and his sound had progressed significantly.

Although still in acoustic mode, the album embraced a broader array of supporting instrumentation, arrangements became looser and Martyn tried to shake off much of the tweeness associated with traditional folk musicianship.

“It was all very cut and dried,” he noted in the BBC’s Johnny Too Bad documentary. “I didn’t like that, never did really although I was quite good at it. I preferred the freedom that I was trying to get across in Bless the Weather because things were not always the same, you know what I mean? It was at that point that I discovered the Echoplex and wobbled off into that direction. That was my hobby at home.”

The six and a half minute, jazz-infused jam that is Glistening Glyndebourne represents Martyn’s first recorded usage of the iconic delay unit, which uses magnetic tape, combined with recording and playback heads, to allow its user to build layers of rhythmic slapbacks and/or long trails of cosmic echoing goodness, depending on the delay time set.

For Martyn, the sonic possibilities afforded by the Echoplex were a game changer. Without having to change instruments – only having to fit a D’Armond electric guitar pickup across his Martin’s soundhole to capture the signal – he suddenly sounded unlike any acoustic fingerstylist who’d come before.

I’d Rather Be The Devil (Devil Got My Woman) – Solid Air (1973)

Released in 1973, Solid Air is typically regarded as one of the high water marks of John Martyn’s career.

Its title track was written for his close friend and fellow tortured musician, Nick Drake, and the LP contains two of his most loved purely acoustic numbers: May You Never and Over The Hill – the latter of which he reportedly recorded using a piece of cardboard instead of a plectrum because, well, he just didn’t have one to hand.

But Solid Air also picked up where Bless The Weather left off in terms of rhythmic and textural experiments. Again, the splice and dice slapback of Echoplex loops are the star of the show on Martyn’s hypnotic reimagining of Skip James’ Devil Got My Woman, which he renamed I’d Rather Be The Devil.

But, before reaching the Echoplex, Martyn also passed his guitar signal through a collection of other effects pedals more commonly utilised by rockers and funksters to alter his dreadnought’s natural tones almost beyond belief.

For example, he liked to use a Gibson Maestro Boomerang Volume/Wah pedal, a Mu-Tron III Envelope Filter, an MXR Phase 90 and an Electro-Harmonix Big Muff to expand his expressive potential, increase sustain and create some seriously squidgy sonics – the like of which you’ll also hear on slightly later tracks like Outside In, Dealer and Big Muff.

It’s well worth checking out his 1973 solo performance of I’d Rather Be The Devil on The Old Grey Whistle Test to get a feel for what he’s actually fretting on the guitar and how much sonic real estate is being filled out by the complex suite of gadgets he’d orchestrated.

Small Hours – One World (1977)

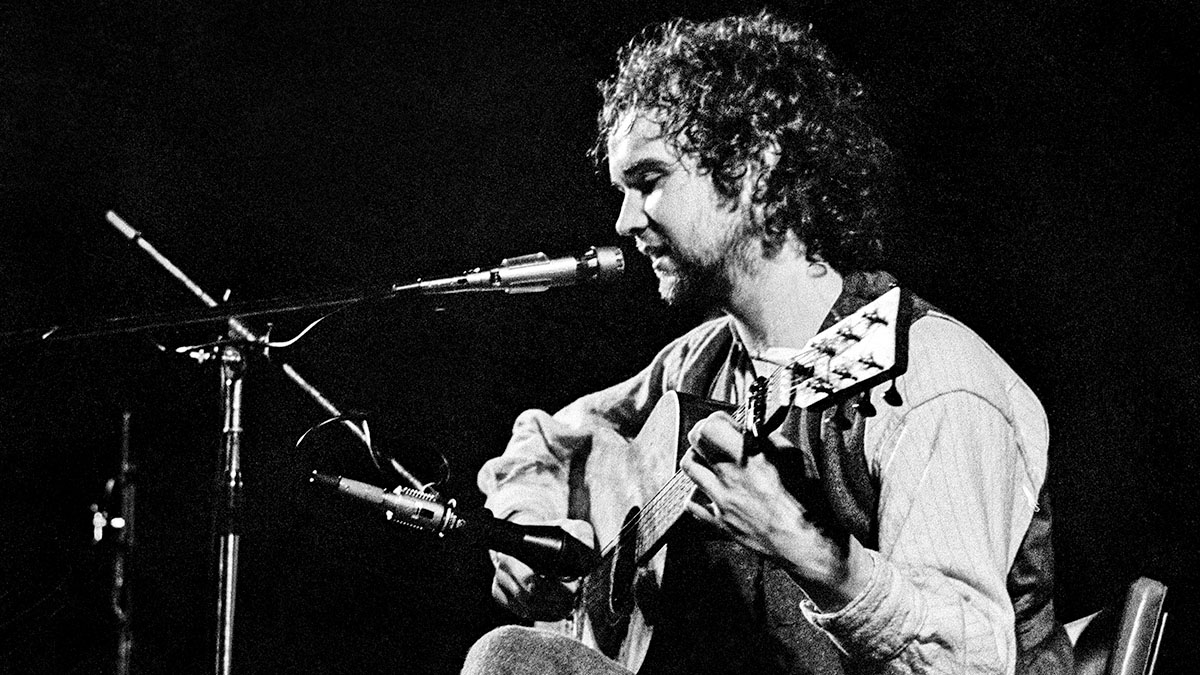

Stretching to almost nine minutes in length, this ambient masterpiece closes 1977’s One World and captures some of the finest and most transcendent guitar work of John Martyn’s entire career.

Interestingly, its downtempo, meditative and infinitely loopable feel has even been credited as a major influence on the burgeoning trip hop movement of the 1990s.

If that doesn’t move you, there’s something wrong with you

Ralph McTell

The piece was recorded outdoors in the early hours of the morning at Chris Blackwell’s rural estate, where the sounds of lapping lake waters and a flock of sleepy geese are clearly audible among the similarly peaceful swells of Martyn’s guitar.

A large outdoor PA system was rigged up by Island Studios engineer Phil Brown to amplify Martyn’s Echoplex-treated chords across the expanse of the lake, with a series of microphones strategically poised to capture the sound as it reverberated back again, along with the gentle movement of the water and the distant murmuring of the birds.

Utilising a long delay time, rather than a rhythmic slap echo, it’s almost as if Martyn had tuned his Echoplex and guitar into the precise resonant frequency of the landscape.

He used his volume pedal to create the ethereal rise and fall of the chords, while minimalist percussion, vocals and some otherworldly Moog contributions from Steve Winwood combine to complete a truly mystical and dreamlike composition. Like a serenade to the breaking dawn, it’s a piece of music that would simply be impossible to replicate in any other space or time.

As Ralph McTell put it in the Johnny Too Bad film, “If that doesn’t move you, there’s something wrong with you.”