This year’s Adelaide Film Festival (AFF2024) had something truly exciting laying in wait: a spotlight on Indian cinema.

While many people are familiar with Bollywood, most don’t know about the vast film industry that exists beyond it. And this is no small market; India is currently the most populated country in the world.

This year’s festival delivered a variety of Indian films from regions and directors that remain underrepresented. From award-winning tales, to a poetic nature documentary, to a sweet coming-of-age story from the North East, the program promises to challenge and expand our understanding of what Indian cinema can offer.

Of all the films I saw, these five spoke to me the most.

All We Imagine As Light

Payal Kapadia’s Cannes Grand Prix winner, All We Imagine as Light, was the film that I’d most looked forward to – and it turned out to be as dreamlike as its title promised.

It’s an ode to the city of Mumbai, also known as India’s “dream-making factory” (and where Bollywood is based). Mumbai is where Indians from all states and of all languages come to fulfil their dreams.

The story follows three female nurses, Prabha (Kani Kusruti), Anu (Divya Prabha) and Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam), who come to Mumbai looking for a better life. Yet they find themselves struggling to belong in a city that refuses to embrace them.

As Kapadia explains: “The film is about not being able to see a way out when one is surrounded by darkness […] that hope doesn’t exist if you have never seen it.”

Kapadia’s storytelling brings a kind of realism rarely seen in popular Indian cinema – not through larger-than-life spectacle or the resplendent city skyline, but through the quiet intimacy of shared apartments, poetry booklets, dinner dates, and small joys and defeats. It is simply soulful.

The film blends themes of female solidarity and friendship with heavier topics such as religious differences, migrant struggles, language barriers and class divides – yet it feels as gentle as rain on skin.

While some have critiqued the film for being too slow (and I admittedly felt this at times), this is exactly how Kapadia managed to turn a city with more than 21 million people into a place that feels completely lonely.

Second Chance

Unlike the vibrant image of India we’re so used to – full of colour, song and lively dances – Subhadra Mahajan’s black-and-white film Second Chance is nothing short of breathtaking.

Set in the snowy peaks of Himachal Pradesh, the film follows 25-year-old Nia (Dheera Johnson) as she retreats to her family’s Himalayan holiday home after a painful breakup and the emotional toll of taking abortion pills. Mahajan captures the stark, quiet beauty of the Himalayan landscape, where time slows down and silence seems to heal.

There, she finds unexpected companions through Bhemi and Sunny. Bhemi, the gentle 70-year-old mother-in-law of the home’s caretaker, is played with a captivating authenticity by Thakra Devi, a local resident and non-professional actress. Sunny (Kanav Thakur) is Bhemi’s playful and curious 8-year-old grandson.

At the top of the world, Second Chance crafts a beautiful and intimate space where we are invited to see that there’s always another chance to find oneself – a chance as infinite and expansive as the snow-capped peaks themselves.

Nocturnes

It’s rare to see films such as Second Chance, which are made in the Himalayas. But it’s even rarer to see an Indian nature documentary such as Nocturnes. The film follows a scientist named Mansi and her indigenous assistants as they chase down thousands of Himalayan moths (particularly Hawk moths).

Directed by Anirban Dutta and Anupama Srinivasan, Nocturnes captures the hypnotic rhythms of field study (something that particularly resonates with me as a researcher).

Fluttering wings and insect trills create a serene soundscape. The close-ups of the moths – their textures, patterns and slight vibrating movements – are fascinating to observe – as the the wider shots of the scientists’ glowing setup in the darkened forest, which drew me in like a moth to light.

Nocturnes is a thoughtful, meditative film that reminds us of how our destruction of the climate can impact these ancient residents of Earth. As the voiceover reminds is, “we most likely cannot survive what the moths have been through.”

Boong

Right from the opening scene, Boong pulled me in with unexpected laughs. The titular character Boong (Gugun Kipgen) is a schoolboy who, along with his best friend Raju (Angom Sanamatum), embarks on a risky journey along India’s militarised eastern border to bring Boong’s absent father back home.

As they make their way, we’re treated to views from Manipur, India’s North East state near Myanmar, which we rarely see in mainstream Indian cinema. Boong itself tips its hat to Bollywood a few times, such as when Raju shows his excitement upon hearing the song Lungi Dance from the Bollywood blockbuster Chennai Express (2013), or when the the chief villager’s secret home cinema is adorned with Hindi film posters.

Director Lakshmipriya Devi does a fantastic job showcasing the region’s vibrant yet complex culture. All the while, she highlights some surprising lesser-known facts, such as how Hindi films were banned in Manipur for years in the name of protecting local culture, language and the regional film industry.

While Manipur’s cinematic potential is still largely untapped, Boong is a brilliant step.

In the Belly of a Tiger

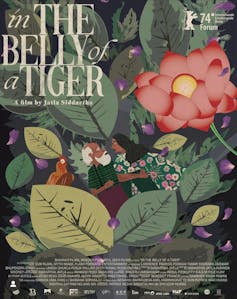

Of the 23 films I saw at AFF2024, In the Belly of a Tiger was a precious gem that stayed with me.

This multinational production (which just won the festival’s Feature Fiction Award) tells a heart-wrenching story of an elderly and desperately poor couple faced with an impossible choice: which one of them will go into the forest to be eaten by a tiger so the other can receive government compensation?

It’s a deeply spiritual and painfully pragmatic exploration of power, sacrifice, love and hope.

The symbolism of the film’s poster hints at its larger themes. Just as Hindu mythology posits the universe emerged from Lord Vishnu’s navel, unfolding like the petals of a lotus, we see how fate, too, blossoms unevenly.

In the film, a poor family in a remote village longs for a better life in the next world, holding tightly to memories of young, innocent love.

Shooting in Hindi, and featuring mostly non-professional actors, In the Belly of a Tiger is both authentic and ambitious. Indian director and cinematographer Jatla Siddhartha collaborated with some of the biggest names in cinema to bring the story to life, including multiple Oscar-winning sound designer Resul Pookutty (who also worked on Slumdog Millionaire).

The music is composed by Japan’s Umebayashi Shigeru, known for his work on Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000) and The Grandmaster (2013). Shigeru’s melodies bring an emotional and magical tone to what is, at its heart, a truly Indian story.

More dreams to share

The films I’ve highlighted here represent some of the most exciting and thought-provoking works coming out of India today.

While the Mumbai-based Bollywood industry is undeniably a huge part of Indian culture, it’s only one piece of the puzzle. These films paint a far richer and more diverse portrait of India, its people, its struggles and its beauty.

They also showcase a glorious future for Indian cinema – one which promises to carry the dreams of a nation eager to share its stories with the world.

Yanyan Hong does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.