The most famous film about a chest-ripping monster is also one of the most beautiful science fiction movies ever made. While some might argue Ridley Scott perfected his cocktail of equal parts depressing and lovely in 1982’s Blade Runner, his first true masterpiece, 1979’s Alien, begins as a sublime, quiet portrait of people getting a bad deal. Today, 45 years after its release, Alien remains a study of artistic precision in both sci-fi and horror, in large part because the movie hides its eventual premise so well.

Because Alien broke ground and spawned a huge franchise, we tend to focus on the first film’s most famous moments: the first chest-bursting scene, Ripley's final battle in the airlock. That leaves the subtlety and beauty of Alien under-discussed. The movie isn’t great because of those scenes; instead, Alien remains brilliant because most of the movie conceals those famous thrills and the now ubiquitous antagonist featured in them.

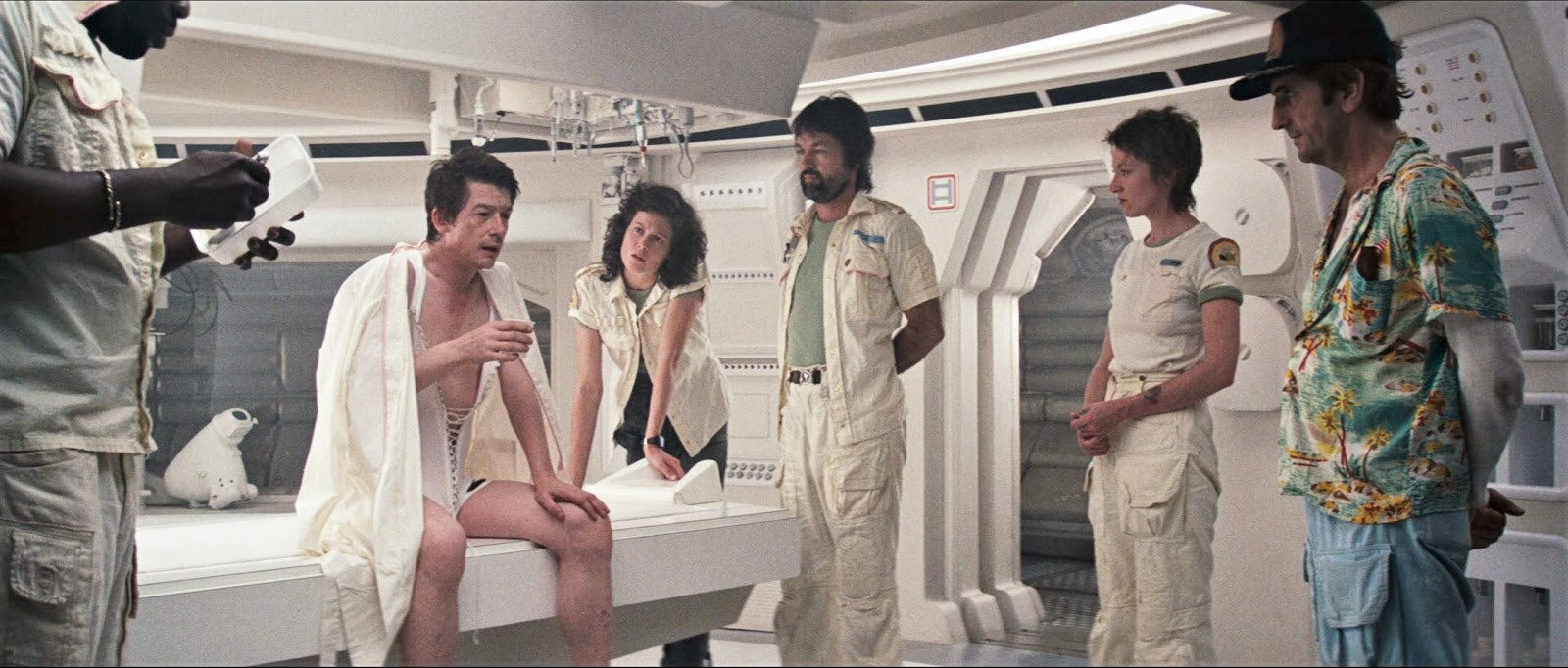

Alien begins in 2122, though the audience barely needs to know that. Scott sets the stage by showing us the space hauler Nostromo. A breeze rustles a book, computers whirr and click, and eventually, a crew of seven people wakes from suspended animation. The moment when these sleeper pods all pop their lids in unison feels aligned with the balletic aesthetic of 2001: A Space Odyssey, but as Kane (John Hurt) wakes up, takes tired breaths, and later chain-smokes cigarettes, the film gives us a nice visual shorthand for its direction. These are ordinary people involved in a doomed space adventure.

Over a meal and coffee, the Nostromo crew talks over each other. These aren’t friends and family, merely co-workers on a long job. Parker (Yaphet Kotto) and Brett (Harry Dean Stanton) are low-key scene-stealers, bantering about their low pay and desire to secure a bonus. When Dallas (Tom Skerritt) orders Parker to his station, Parker deadpans, “Can I finish my coffee? It’s the only thing good on this ship.” This is the kind of detail that makes Alien work. Although we know almost nothing yet, we buy that these are real people. Not heroes. Not even astronauts. Just workers who want to have a smoke and finish their coffee before they get back to the grind.

For the first 20 minutes, both audience and crew are kept in the dark about what’s really going on. The Nostromo was supposed to wake the crew when they returned to Earth, but now they’ve been ordered to check out a strange signal. Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), doesn’t even seem to be the main character, instead emerging as the most reasonable voice because she deduces that the signal they're investigating isn’t an SOS, but a warning. In other horror movies, the voice of reason is usually just another victim.

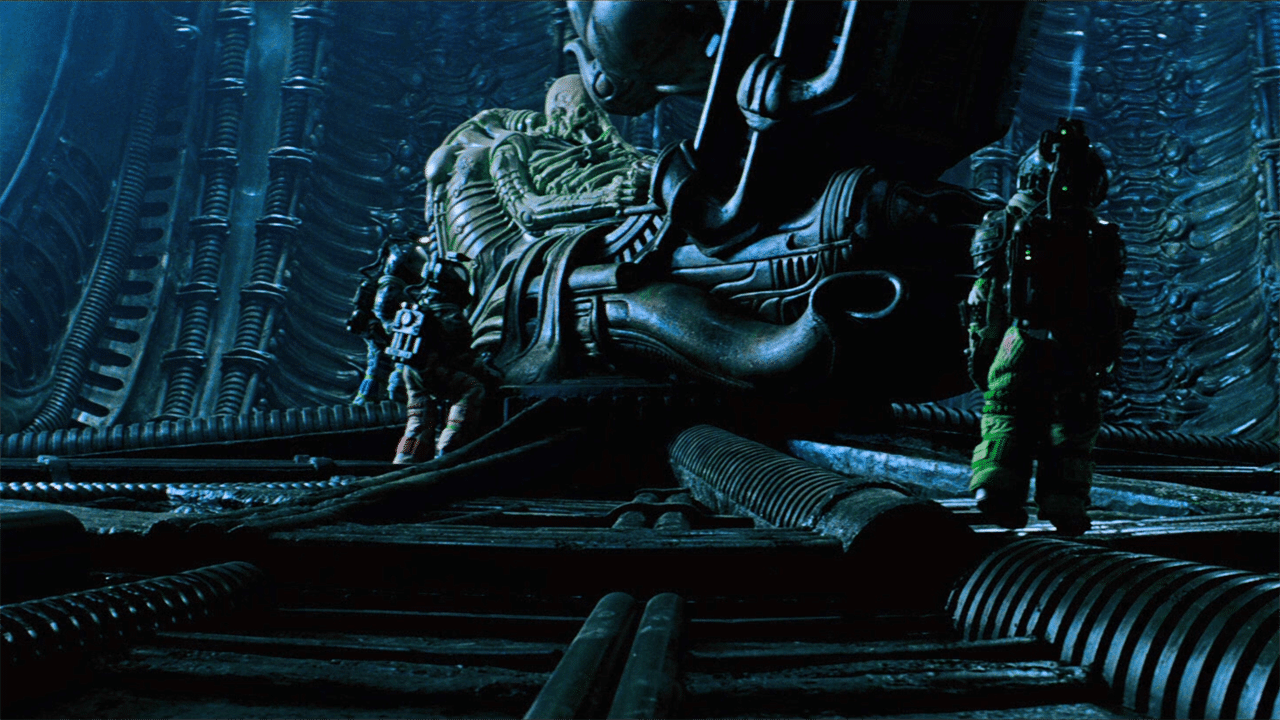

But it’s a subtle plot twist that makes Alien so gripping all these years later. The murderous xenomorph doesn’t come aboard because some hapless human explorers accidentally picked it up; it was obtained on purpose. And, when Ash (Ian Holm) is revealed to be, as Parker says, “a goddamn robot,” Alien layers its world-building in a way that works thanks to a perfect balance of skilled direction, solid writing from Dan O’Bannon, and strong artistic design from H.R. Giger and Chris Foss.

These sensory components of Alien — the sound design, Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack, the creature and spaceship design — aren’t remarkable in isolation, but are tremendously compelling when used together, which is one reason why various Alien sequels and prequels have failed to live up to the artistic integrity of the original. Attempts by Prometheus and Covenant to recreate and retcon certain scenes only prove why the first film is so brilliant; it used its best weapons sparingly. From Sigourney Weaver’s delayed prominence to how little we actually glimpse the alien, nothing is overplayed.

Somewhat famously then, but largely forgotten now, none of the trailers or other press in 1979 revealed anything about the alien. Its appearance was so well-hidden that even the novelization’s writer, Alan Dean Foster, wasn’t given a detailed description, forcing him to spin a vague portrait of the xenomorph.

That’s what truly makes Alien great. The mood of early trailers and photos were enough to get people interested. You could imagine a version of Alien without the alien, and you would still be curious about the Nostromo’s fate. Watching today, the start of the xenomorph’s rampage almost feels like a bonus. The film’s restraint remains remarkable, and for as famous as its tagline, “In space, no one can hear your scream,” has become, it’s easy to misunderstand its meaning. The power of Alien is that it's a quiet movie that sneaks up on you when you least expect it.