If you watched every single science fiction movie released between December 1979 and December 1984, you would have been confused. Not only did many of these sci-fi films kinda look similar, but they sounded somewhat similar, too. 2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984) and Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) both tried to assert that pew-pew Star Wars action was out, and ponderous, slow-moving space mysteries were in. After adding some massive starships and a dash of ominous music, complete with a cosmic BRAAAM, the recipe was complete. And on December 21, 1979, the there was the strangest Disney movie of all: The Black Hole.

But just like 2010 and The Motion Picture are very different movies once you get down to the details, The Black Hole is also a vintage sci-fi snowflake. It’s long been derided and mocked for its tonal incongruity and scientific inaccuracies, but lurking underneath its problems is a great movie that’s quite literally one of a kind. Forty-five years after its release, it's worth another look.

The Black Hole tells the story of a lost spaceship, the Palomino, encountering another lost spaceship, the Cygnus. The difference is that the Cygnus has been lost for two decades, and now sits cozily next to a black hole, maintaining its position with bespoke anti-gravity tech created by lunatic genius Dr. Hans Reinhardt (Maximilian Schell). The small crew of the Palomino consists of a fairly generic group of space travelers, Captain Holland (Robert Foster), Charlie Pizer (Joseph Bottoms), and Dr. Durant (Anthony Perkins). These yawn-inducing non-characters are overshadowed by the only woman in the movie, Dr. Kate McCrae (Yvette Mimieux), the kooky Harry Booth (Ernest Borgnine), and, crucially, Roddy McDowall as the voice of the cutesy but spunky robot known as V.I.N.CENT.

Without V.I.N.CENT. and the hilariously creepy Reinhardt, nothing about the movie would work. Like the original 1956 Forbidden Planet, the characters in The Black Hole are almost entirely forgettable, except for the cool robot and the megalomaniacal baddie. Critics have compared Hans Reinhardt’s behavior to that of Captain Nemo in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, but thanks to the omnipresent film score from John Barry, Reinhardt scans more like a Bond villain in a sci-fi movie that forgot to include James Bond.

If all this sounds like The Black Hole is a bit of a mess, that’s because it is, as the basic concept went through several writers and directors before becoming the first PG-rated live-action Disney movie. It just doesn’t know what sort of movie it wants to be. Is it a family-friendly space romp in the style of 20,000 Leagues? Or is this a darker, more twisted horror story that just happens to have a cute robot?

The Black Hole is both and neither, and it's in those contradictions that the movie is accidentally brilliant. Ultimately, The Black Hole is great because it’s a space mystery. Why is Reinhardt still on the Cygnus? What’s the deal with his zombie-like android servants? How come the blade-spinning enforcer robot, Maximilian, is such a jerk? While the film answers some of these questions, others just become the fabric of the movie, making constant strangeness part of the viewing experience.

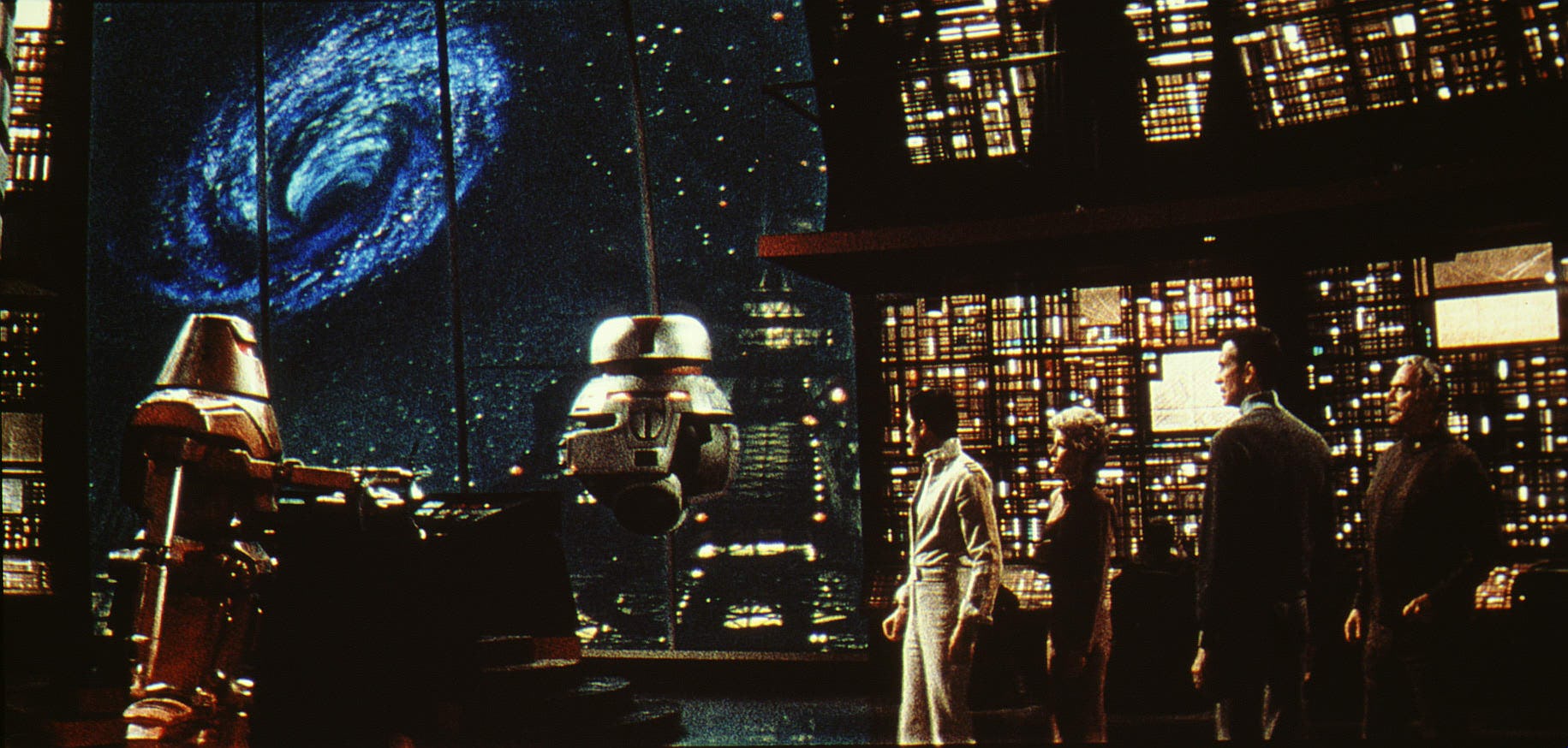

The big twist is not only fun, but one of the grisliest moments ever put in a Disney movie. The biggest reason the movie is worth watching, however, is for its aesthetics. There’s a lavish use of matte paintings created by legendary designer Peter Ellenshaw and his son, Harrison, all of which give the film a unique and rich quality. You feel like you’re in a painting for half the movie, which elevates the material into the realm of borderline surrealism. Whether or not you buy anything that’s happening hardly matters when the Cygnus looks this cool. The physics of the black hole is utter nonsense, but who cares when you see how incredible the effect of the vortex looks?

No modern sci-fi movie could look like this, because the techniques used to make The Black Hole were a strange blend of the past and the future. Most movies didn’t use this many matte paintings back then, and you certainly don’t see gorgeous space art in modern sci-fi movies today. Legend has it that 150 matte paintings were created for the film, but that only a handful were actually used. That detail is the perfect way to think about The Black Hole. It’s essentially an exercise in visual and sonic art, but one that wasn’t entirely realized in its final product. The version of The Black Hole that we got is deeply imperfect, but the beauty and strangeness in that imperfection is incredible and unique.