On February 18, 1983, noted mob movie peddler Martin Scorsese’s black comic masterpiece The King of Comedy premiered to mostly warm reviews and negligible box office results. On October 4, 2019, Todd Phillips’ Joker, a Hot Topic King of Comedy knockoff and standalone origin story for Batman’s archnemesis, met bumpier reviews that belied its record-breaking opening weekend haul.

In the 36 years between, the former’s enormous cultural influence paved the way for the latter’s ticket sales, but for their obvious family resemblance, Joker is the mismatched heir to The King of Comedy’s legacy. Who is the Clown Prince of Crime without the Dark Knight? Moviegoers flocked to multiplexes to find out, unwittingly and immediately highlighting an important discrepancy between Phillips’ supervillain character study and Scorsese’s late-night TV satire: their measurements of success.

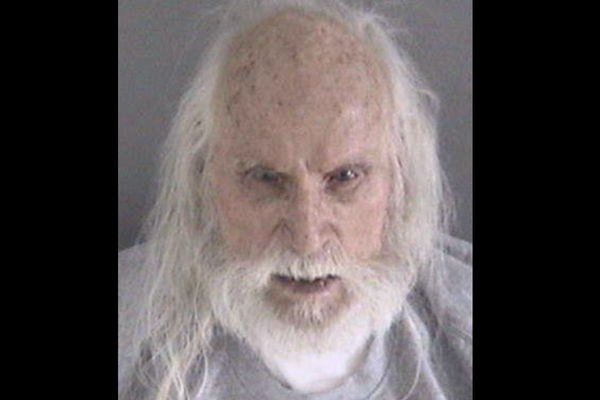

Audiences in 1983 passed on The King of Comedy’s rags-to-prison-to-riches formula, where wannabe funnyman and born loser Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro) stalks, hectors, and finally abducts his idol, megastar comedian and talk show host Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis); the best way break into the big time, Pupkin reasons, is to hold the big time hostage. Like the film itself, Pupkin is brushed off by the public, as well as his mother (never seen, but voiced by Scorsese’s own beloved mama, Catherine Scorsese), his dream girl, Rita (Diahnne Abbott), the late-night TV apparatus, and especially Langford.

At least Langford has a good reason to ignore Pupkin, who makes workaday obsessive fans look easygoing. Pupkin is incapable of taking “no” for an answer to any question he poses, and as good as he is at lying to others, he’s incredible at lying to himself; there’s an especially excruciating scene at Langford’s country home, where Pupkin shows up uninvited with poor Rita in tow, that drives home Pupkin’s self-delusion with blunt force trauma. But 20th Century Fox had no clue how to market that kind of picture, and besides, anti-comedy didn’t complement the national mood at the decade’s onset.

Bombing at the box office suits The King of Comedy, though, given Pupkin’s strained acquaintance with success; there’s no more complimentary reception for this film than a chorus of crickets. The King of Comedy didn’t have to lose millions of dollars for its production company just so Scorsese could make his point. But there’s a kismetic relationship between Pupkin’s arc and the film’s commercial stumble: Pupkin fails upward, the movie flopped, and both reshaped pop culture writ large along their way. A world without The King of Comedy is a world without The Cable Guy, 30 Rock, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Observe and Report, The Larry Sanders Show, The Office, and any flavor of Alan Partridge.

Sidling next to these movies, shows, and comedy acts, Joker looks starkly out of place, which is a punchline unto itself. The King of Comedy echoes through each of these titles by degrees. In contrast, Joker steals its entire blueprint; copy, paste, and make a few minor changes to the plot, and you’ll end up with two virtually indistinguishable synopses. Outside of the Batman comic canon, there is no greater influence on Joker’s atmosphere than The King of Comedy, amounting to colossal wasted effort.

For one thing, Joker has other rich source material to crib from: Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke, which traces the Joker to his days as a stand-up comic aspirant, with fatherhood on the horizon and a wife who loves him unconditionally. Then he has “one bad day,” the catalyst for turning any average Joe raving mad according to no higher authority on madness than the Joker himself, and a legend is born. For another thing, The King of Comedy’s tone is antithetical to the goals of tentpoles like Joker, which makes Phillips’ choice to use it as his film’s basis puzzling at best.

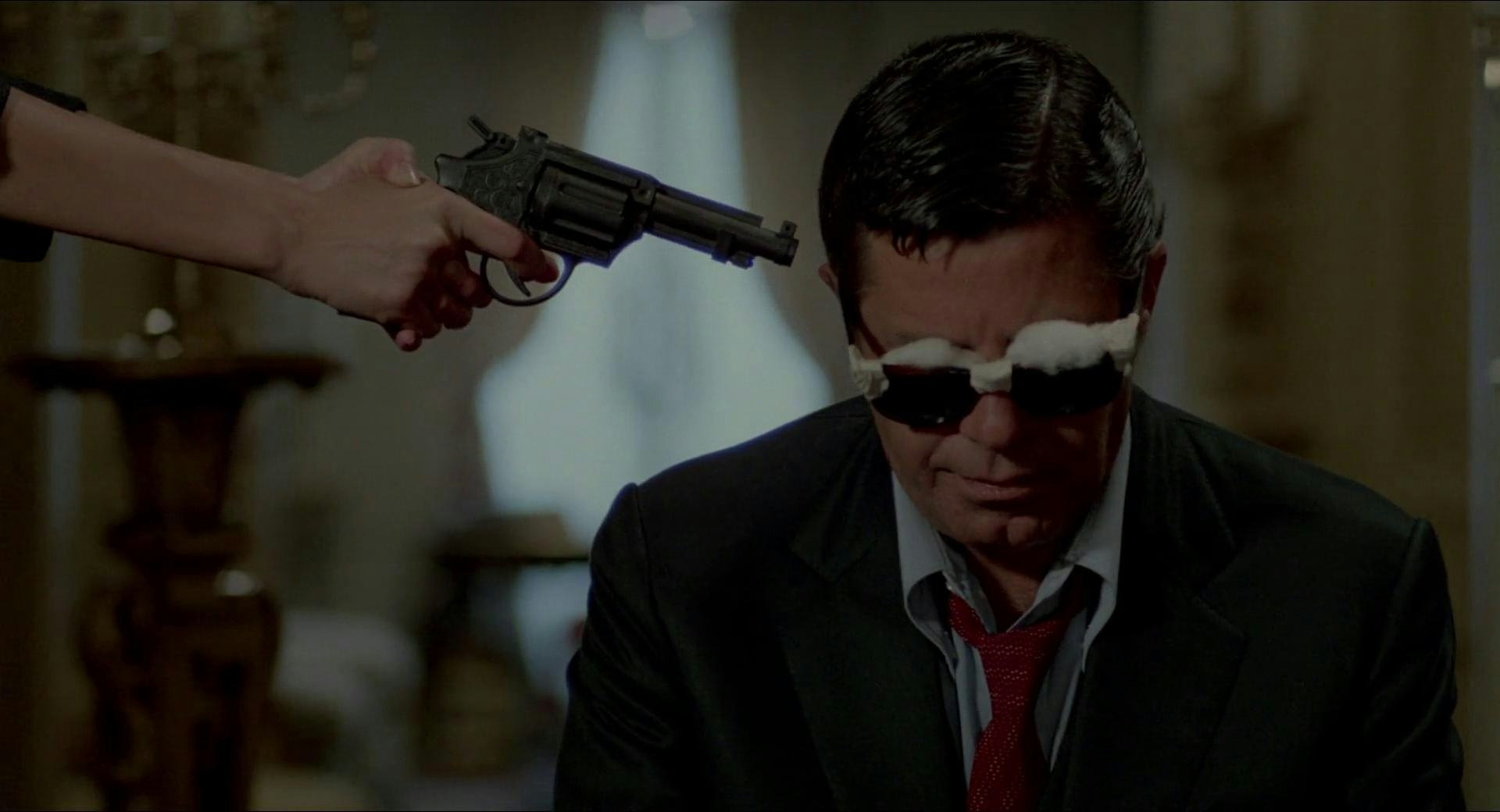

Joker signals its audience how to feel about Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), the man fated to don grease paint and watch Gotham burn, but characterizes him in the interim as the saddest of sacks, like Tracy Jordan’s Oscar-winning prestige drama Hard to Watch filtered through the DC brand. Everything goes wrong for Arthur: he lives in a grungy flat with his sickly mother (Frances Conroy), who isn’t actually his mother and who eventually winds up in the hospital from a stroke; he gets beaten up working his day job, which he promptly loses; he has a disorder that triggers his laughter at wildly awkward moments; the government program he gets his meds from gets shut down.

There is no other dimension to Arthur other than his relentless pitiability, and because there is no other dimension, Joker is hardly The King of Comedy at all, despite being contextualized as its distant kin in any number of reviews from the film’s world premiere at the Venice International Film Festival. Rupert Pupkin, on the other hand, has countless dimensions: sympathetic, psychopathic, clear-eyed, unhinged, gentle, violent, narcissistic, honest, consummately false, charming, grating.

That’s a lot to fit into any character, but Pupkin has the capacity. The Joker doesn’t. He’s a preexisting personality. Attempting to make him in Pupkin’s image creates dissonance in the character as defined by Bill Finger, Bob Kane, and Jerry Robinson; it’s a consequence of using pop cinema as a vehicle for a Scorsese riff. The King of Comedy’s other descendants don’t have this problem. They have their own identities; they’re cousins to The King of Comedy, not botched clones. 40 years after its release, we know who Rupert Pupkin is. We know what he wants. He isn’t the Joker. Or, put the other way, the Joker simply isn’t Rupert Pupkin.