Last week, police seized about 80 illegal firearms across Victoria. These included eight homemade firearms, four of which were “military-style weapons”, as well as two 3D printers.

This is the latest in a series of seizures of 3D-printed weapons in Australia:

in 2016, Queensland police discovered a 3D printer in a raid on a “large-scale” firearms production facility

in September 2021, New South Wales counter-terrorism police arrested a right-wing extremist for possession of a digital design file that could be used to print a 3D gun

in June 2022, Western Australia police seized a 3D-printed semi-automatic rifle including metal parts that could render the gun fully operational.

Despite media reports of seizures of 3D-printed guns, very little is known about the demand and availability of these firearms within Australia. The available research, including our own, draws heavily from media reports.

What are 3D-printed firearms and why are they such a threat?

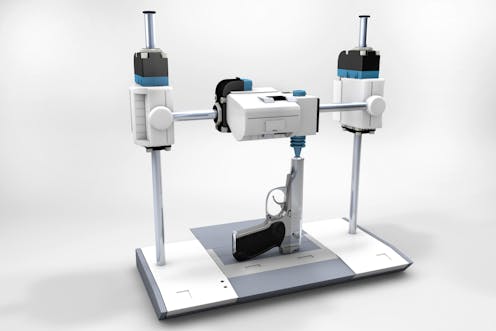

3D printing is used to create a three-dimensional object by layering materials following instructions contained in Computer Aided Design (CAD) files. These files can be downloaded on dark web forums, for example, and shared via online networks.

3D-printed firearms can include handguns, rifles and machineguns. There are also modular or hybrid guns made from interchangeable firearm components (3D-printed or otherwise). This allows for customisation and cloaking of a firearm’s history.

3D-printed firearms do not currently work as well as traditional guns. However, there have been rapid improvements in the reliability of 3D-printed firearms and they are becoming less prone to malfunction.

3D-printed guns pose a significant threat to community safety. 3D printing has evolved to become relatively cheap and easily accessible. Significantly, it allows the manufacture of operational weapons within an otherwise heavily regulated firearms context.

Such guns are untraceable as they don’t have serial numbers nor do they leave ballistic evidence in the same way as conventional firearms. This can undermine police investigations and information systems such as the Australian Ballistics Information Network and the National Firearm Trace Program.

These weapons are potentially available to people who aren’t licensed to own a firearm, and those under Firearms Prohibition Orders. This includes those who could not hold a firearms licence due to their age, mental health, or criminal histories.

What’s more, these weapons are made mostly from plastics, which means they aren’t detectable with metal detectors. Such firearms can bypass traditional security screening measures, presenting serious risks in aviation, public events and locations where security screening is in place (for example mega events, or secure government buildings such as Parliament House). 3D-printed guns are also easier to dismantle and destroy than more durable metal-based firearms.

Police have revealed some organised criminal groups and extremists have had 3D printers and 3D-printed firearms in their possession.

Recent Australian research in which one of the authors, David Bright, was involved, found criminally connected individuals, including members of organised criminal groups, can easily access a range of firearms through social networks. We interviewed 75 people imprisoned for gun crimes and found some had manufactured firearms or firearm parts. However, some interviewees were suspicious of accessing digital design files for fear of leaving online traces that law enforcement could intercept.

Members of extremist groups are less likely to have the contacts required to access the Australian black market for firearms. For them, 3D-printed firearms may be an attractive and low-risk option.

Read more: 3D-printed guns may be more dangerous to their users than targets

How could we respond?

It’s important to note Australia has one of the strictest gun control regimes in the world. Any home manufacture of any firearms is criminalised under existing laws.

Legislative responses to 3D firearms have varied internationally, and across Australian jurisdictions, and are evolving given the dynamic nature of the problem. International responses to 3D-printed guns include:

criminalising the manufacture of 3D-printed firearms

licensing or registration schemes for 3D-printed firearms

introducing new offences for possession of digital design files for 3D-printed firearms.

While Australian states have uniform legislation on the restriction of firearms, different states have enacted different laws for 3D-printed firearms and their design files. NSW is the only Australian state to criminalise possession of digital design files for 3D guns.

There are some alternative legal and policy responses. “Hash values” might be used to eradicate digital design files from the internet. Hash values are codes associated with images and files, sometimes referred to as “photo DNA”.

Police and technology companies already use these to detect and remove child exploitation material. This could be used to restrict access to 3D weapon digital design files. However, unlike child exploitation material, design files for 3D printed guns are not universally illegal.

One innovative approach would be to require 3D printers sold in Australia to recognise digital design files for 3D-printed firearms. This is turn could prevent printing in such cases.

Online censorship, content moderation and website blocking are other possible options. However, these are complicated by the fact the possession or dissemination of design files for 3D-printed firearms isn’t currently illegal (unless you’re in NSW). There are also a range of issues with online censorship, such as free speech, the cross-jurisdictional nature of the internet, and the availability of design files on the dark web.

Another possibility for restricting access to digital design files would involve the development of industry online safety codes. These are codes that regulate access to harmful online conduct, similar to the Online Safety Act.

There’s perhaps a greater role for the e-Safety Commissioner to direct platforms or websites accessible in Australia to remove harmful content such as design files for 3D-printed firearms, or restrict access to those over 18. Again, though, there are a range of issues with online age verification systems.

There is a pressing need for more research on 3D-printed firearms in Australia. Given the relative safety we enjoy in Australia by virtue of our tough gun laws, there are serious concerns about the ease of availability of digital design files for printing firearms. Restricting the capacity to manufacture firearms is our best defence to ensure our safety.

David Bright receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Australian Institute of Criminology.

While employed at the Australian Institute of Criminology, Dr Monique Mann worked on the evaluation of the Australian Ballistics Information Network (ABIN). Dr Mann is Vice Chair of the Australian Privacy Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.