When the Covid-19 pandemic hit Hong Kong nearly nine months ago, sending everyone away from offices and schools and into their tiny flats, architect Marisa Yiu Kar-san started thinking about how even the smallest things could make a big difference when your life has shrunk to the size of your home. She decided to put out a call for interesting ideas.

“These are small objects in response to the pandemic,” says Yiu, the co-founder of Design Trust, a charitable organisation that promotes design. “They should fit in the palm of your hand.”

The response was enthusiastic, with a total of 76 submissions from designers, artists and architects in Hong Kong and around the world. Faced with travel restrictions and closed borders, British designer Sam Jacob made a globe printed not with a world map but with diagrams of interior spaces. Hong Kong textile artist Movena Chan was also inspired by the newly inaccessible world beyond her home; she shredded maps and wove them together into a small tapestry.

These projects and many more are now on display at Soho House in Sai Ying Pun on Hong Kong Island, where Design Trust’s “Critically Homemade” exhibition takes place until October 4. But these objects could survive well beyond then. While Jacob and Chan’s projects are conceptual in nature, others are more practical, and Yiu says Design Trust is looking to work with companies to put them into production.

That’s likely to be the case for industrial designer Michael Young’s contribution to the programme. He took a straightforward approach to dealing with the pandemic by designing door handles that use laser etching to create fluid-repellent antibacterial surfaces. Young says he was inspired by the surface of lotus leaves, which naturally repel water.

“It’s pretty simple – just adding a bit of science to an everyday object,” he says. The handles have already found a home in a meeting room he is designing for Hong Kong-based office design company JEB Group. “I hope to employ the research in future reiterations.”

Aron Tsang Wai-chun and Hera Lui, of Hong Kong-based Napp Studio, tackled another problem related to the pandemic: stress and anxiety. Inspired by sensory toys used for children’s therapy, they developed Tactile Family, a set of objects made from wood, stone, steel and silicone rubber whose shape and tactile qualities are meant to calm nerves. Smiling faces are etched into their surfaces.

“During the intensive lockdown times, we heard my neighbour’s kid screaming every now and then,” says Tsang. “I understand that the stress built up subconsciously is so serious that [people], especially children, have difficulty in letting it out. So we thought about the idea of making some tools as a response. Holding them in your hands is just a sense of pleasure.”

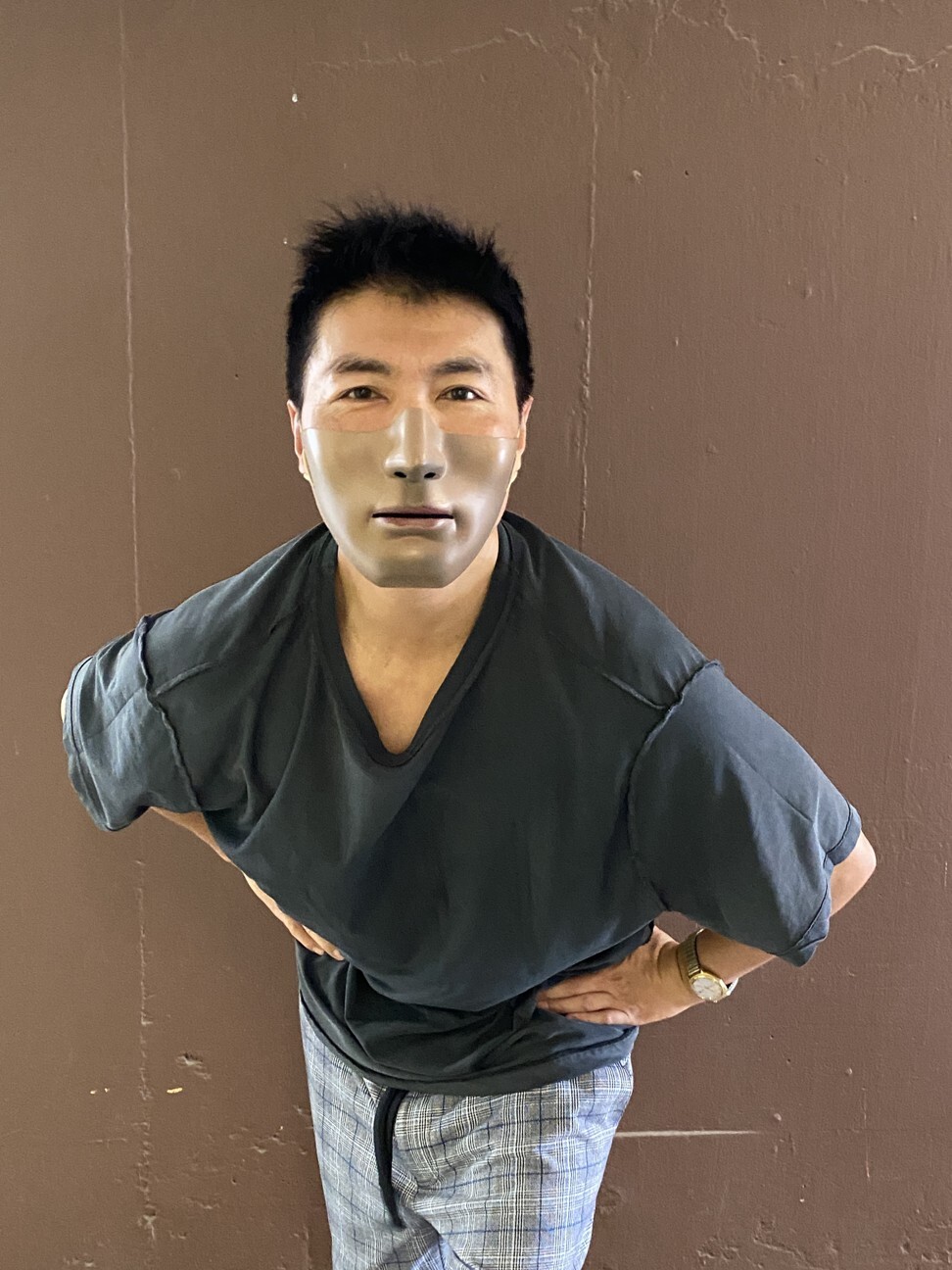

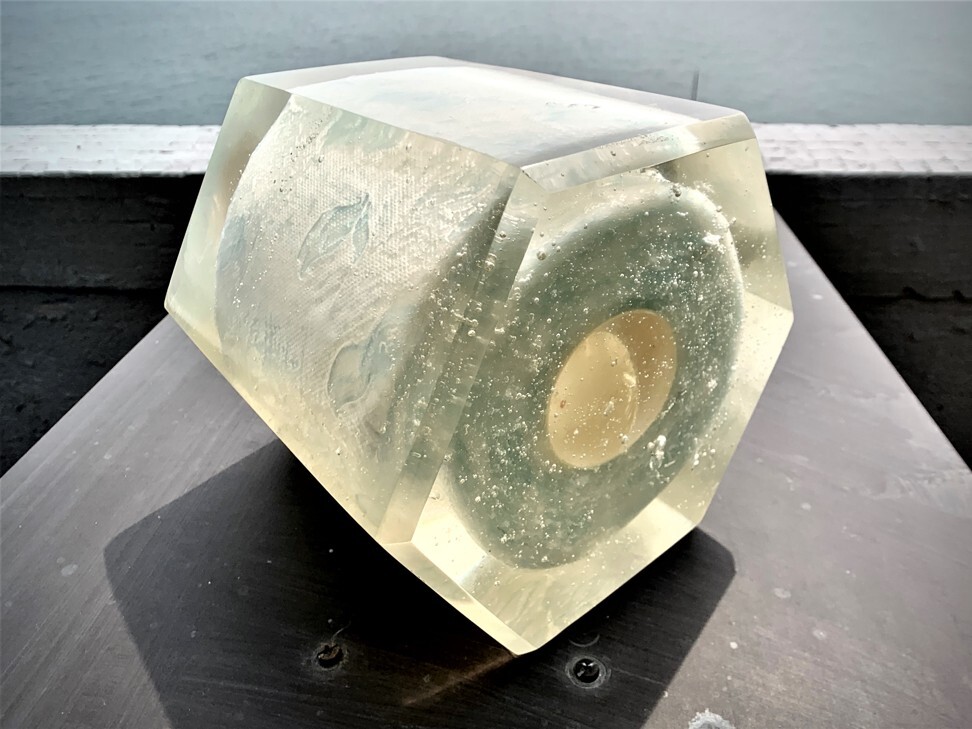

Other projects push the bounds of pandemic-related creativity. G.O.D founder Douglas Young created the 3D Printed (Superman) Face Mask, which allows people to replicate their own face as a covering. Artist Kacey Wong embalmed Covid-related objects, including toilet paper, in resin that is cut and polished like diamonds.

Frederic Gooris and Paulina Chu made a set of home exercise tools out of bamboo, an eco-friendly material. And JJ Acuna , of JJ Acuna / Bespoke Studio, created a takeaway shrine. “ Meditation saved me this year,” he says. “It’s really great for perspective.”

Still other projects used the lockdown experience to connect what is happening on the streets of Hong Kong with the domestic environment. Architects Kevin Mak King-huai and Ken Fung Tat-wai, founders of the group Street Signs Hong Kong, whose goal is to record and preserve the city’s traditional shop signs, created Streetsign-Fashioned, a set of moulds for making cocktail ice cubes.

Each mould is based on the hand-painted calligraphy of vintage signs. They serve as a reminder of the craftsmanship inherent in these signs as well as their rapid disappearance from the city’s streetscape, a result of changes in government regulations.

To make the moulds, Mak and Fung worked with second-generation signboard maker Lee Kin-meng, who created a digital font based on the works of veteran calligrapher Lee Hon. “We used melting of ice as an analogy to the disappearance of the signboard streetscape in Hong Kong, which we hope will receive enough attention and initiate discussion on its preservation before it is too late,” says Mak.

Jesse McLin and Julie Progin, founders of local design firm Latitude 22N, also found inspiration in Hong Kong’s heritage. Their project Pocket Garden is a playset based on the scholar’s rocks that once populated Tiger Balm Gardens, the beloved Tai Hang theme park that was demolished in 2004.

Progin says they used waste materials collected from around their studio, including porcelain, yarn and stale popcorn. Each piece sits atop a brick that can be snapped into Lego bricks and wheels.

Expect to see those pieces for sale at some point in the future.

“We’re not looking to mass produce our concept given that each set of sculptures is unique and handmade,” says Progin. “The project works when every piece we make has its own character, just like each rock tells a different story. The idea would be to start small with a numbered edition and see where it takes us.”

Marisa Yiu says the designs are a sign of how the creative process can thrive in the most difficult circumstances.

“People were willing to share ideas despite personal and professional challenges during these times,” she says. “I’m really hoping some of them can become reality.”

From our archive