The best games don’t just conjure their gameplay out of thin air. They pull on memories, making their gameplay a metaphor for real-life experiences. They may reinterpret their inspirations so fully that the game bears little resemblance to the experience it’s modeled after, but the source remains, buried somewhere in the game’s code to tether it to the real world.

The story of how Shigeru Miyamoto’s childhood inspired The Legend of Zelda is so well known it’s practically a foundational myth of game design. As the story (vaguely) goes, Miyamoto spent his childhood in Kyoto exploring the woods near where he lived, and that experience later inspired The Legend of Zelda.

Miyamoto himself has shared more detailed versions of these events over the years. In a 2010 New Yorker profile, Miyamoto recalls finding a small cavern in a bamboo forest near a shrine in his hometown of Sonobe and peering into the mysterious underground world with a lantern. A 2015 NPR interview includes the story of a hiking trip Miyamoto took in Kobe. On this trip, he scaled a mountain with his elementary school class, where he says he was “amazed” to come across a lake at the top. All of these experiences left their mark — particularly, it seems, the feeling of navigating treacherous, confining terrain to discover a glimpse of natural beauty at the end.

The Legend of Zelda is a story of saving the world, of defeating a great evil, and of saving a princess. Despite the world-shaking events of its plot, The Legend of Zelda’s emotional ambitions hit much closer to home. More than anything else, The Legend of Zelda is a story of childhood wonder. Learning your way around an unfamiliar world, testing yourself against larger-than-life trials, and getting lost in the unexpected beauty around you — these are hallmarks of growing up and pillars of The Legend of Zelda.

Sure, we may not have grown up slaying monsters with a magic sword, but Link’s quest to defeat Ganon mirrors childhood experiences all the same. The parallels don’t need to be one-to-one when the feeling behind the game evokes childhood wonder and discovery at every turn. Navigating the Lost Woods is nothing like getting lost on your way home from school, but the frustration and fear feel the same. You may not know what it’s like to stumble upon a life-saving fairy in an enchanted lake just when you need her, but you’ve probably felt relief and gratitude when a stranger helped you out at just the right time.

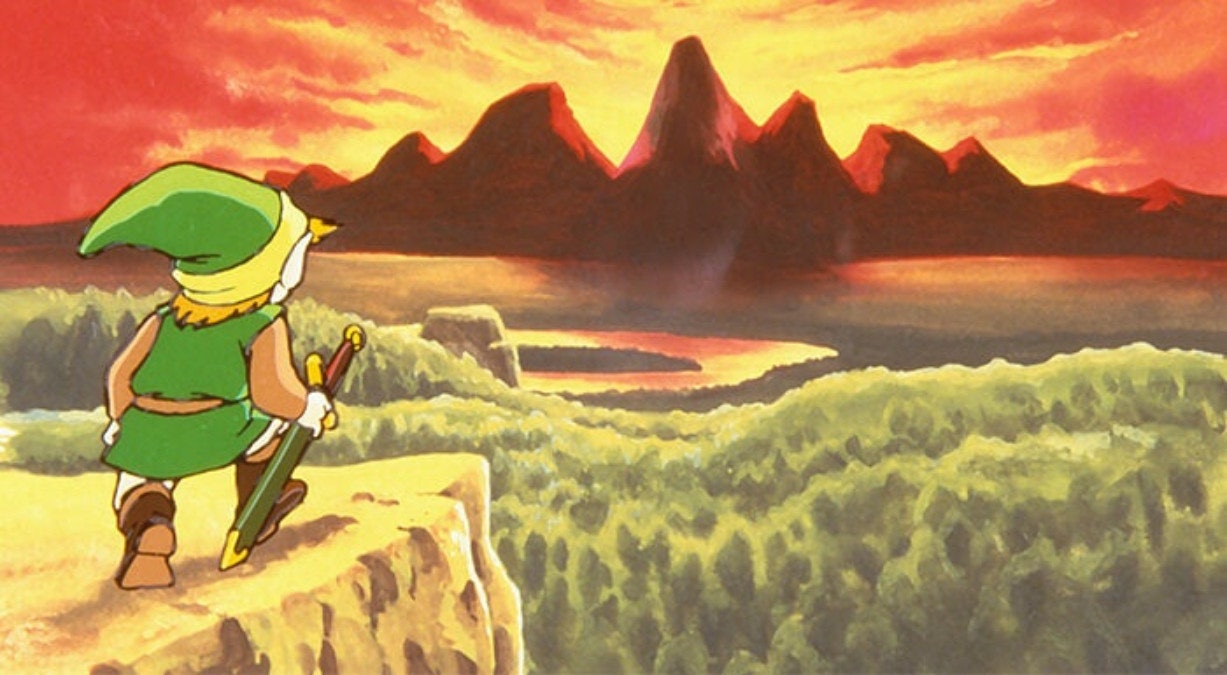

You don’t need to have explored the same Kyoto woods as Miyamoto to see how his childhood experiences formed the foundation of The Legend of Zelda. The version of Hyrule presented in the first game is a mountainous landscape dotted with dark, dangerous caves and serene lakes. Around every corner is a new obstacle, but beyond them lies all the beauty the NES could muster at the time. The Legend of Zelda encourages exploration and experimentation, not just passively taking in the scenery.

Imagine every game you’ve played up to this point takes place in essentially static levels. There might be a secret path or two, but you can’t really affect the environment you’re in. Then imagine you’re playing The Legend of Zelda. On a whim, you equip your candle and send its flame in the direction of one of the hundreds of identical trees filling its world. Instead of harmlessly passing over it, the flame burns down the tree to reveal a hidden set of stairs leading to a mystery below. It may sound mundane now, but when The Legend of Zelda was new, it changed the way everyone looked at video games forever.

Upon its 1986 launch in Japan, The Legend of Zelda was an immediate and overwhelming success, selling 1 million copies on its first day. It came stateside in 1987, becoming the first NES game to pass the 1 million mark in the U.S. by the end of the year. No list of the most influential games today would be complete without it, and the series has only grown more popular as time goes on.

The Legend of Zelda is commonly cited as a foundational RPG, even though Miyamoto might not necessarily agree. In a 1992 interview for The Super Famicom magazine, Miyamoto says The Legend of Zelda is actually a “real-time adventure,” noting that progression is more about player skill than character stats.

Since then, the Zelda series has leaned more into RPG elements, but it still has the spirit of an adventure game. You might find better weapons, add more hearts to your health bar, or power yourself up with magic rings, but real progress comes from practice and exploration, not from increasing a number on your character sheet.

No matter how much The Legend of Zelda has grown and changed since the original game’s release, the idea at its heart has remained the same. Whether your first experience with the natural grandeur of The Legend of Zelda involves riding Epona through the fields of Hyrule, sailing the Great Sea aboard the King of Red Lions, or hang-gliding down from the heights of the Great Plateau, you’ll still feel that spark of childlike glee that elevated the original from a great game to a legend.