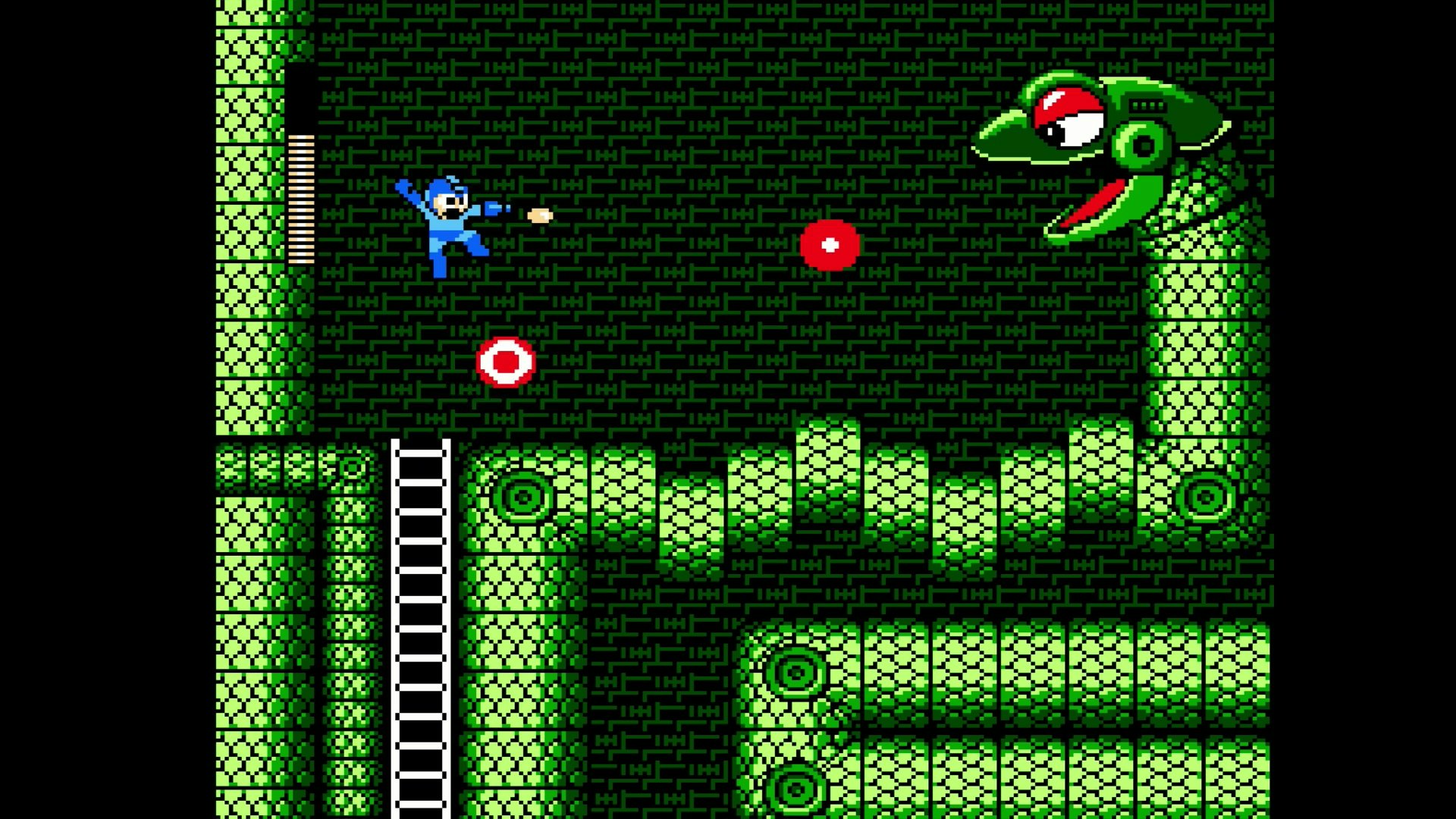

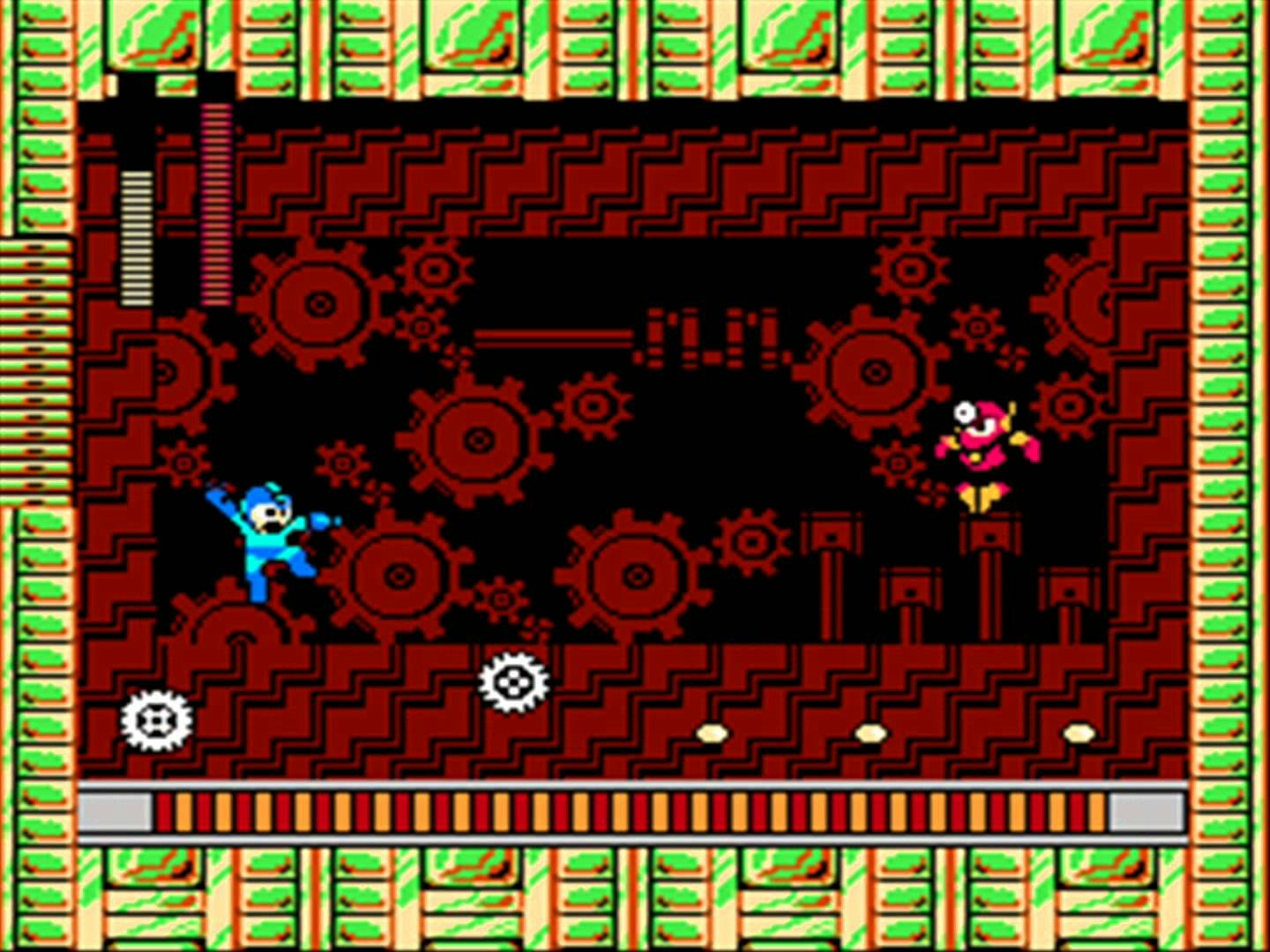

Takashi Tateishi is a genre bender, a melodist who poetizes anomalous grooves. The Japanese composer is best known for writing and recording the music for 1988’s Mega Man 2 – an original 8-bit soundtrack that turned the Nintendo Entertainment System’s limitations into a synth-heavy odyssey that drifts through pockets of Mezzoforte, lo-fi dream pop, and 70s-tinted jazz fusion. It’s noteworthy for the way it flowed an era of piano-orientated compositions into guitar motifs, but as the Blue Bomber sequel celebrates its 35th anniversary this December, it is also a reminder of a transition in experimentation for Tateishi and Capcom at large.

“In my youth, I was confident in my musical talent and I wanted to express the groove of a band’s sound in game music,” Tateishi tells Inverse. “I was in an amateur band and we played pop and rock songs. But the music of Mega Man 2 is very close to the genre I used to play in the band.”

An aspiring keyboardist, Tateishi replied to a Capcom job listing in the late ‘80s. His demo tape fit the company’s desire for “musical knowledge over coding” and his debut project was the 1988 arcade title LED Storm, otherwise known as Mad Gear in Japan. It didn’t sell well, at all, but with Capcom being a tight-knit collective divided into arcade and consumer divisions, Tateishi was able to create alongside Akira Kitamura (Mega Man), Keiji Inafune (Mega Man), and Yoshiki Okamoto (Final Fight), and composers Yoshihiro Sakaguchi (Street Fighter), Manami Matsumae (Mega Man), and Harumi Fujita (Bionic Commando). He adopted the pseudonym “Ogeretsu Kun” and was assigned to Mega Man 2 — a sequel that wasn’t initially greenlit by management due to the Famicom’s design, but with Kitamura and Inafune as leads, was made in just three months.

“The ways to express music are limitless.”

While most synchronized albums are defined by an era, Mega Man 2’s soundtrack inhabits artsy inaccessibility that is versed in decades of experimental jazz-pop fusion. It’s a lesson in margins, modifying the Famicom into an 8-bit love letter to influences such as Toshiki Kadomatsu’s Sea Is A Lady and Yellow Magic Orchestra’s Technodelic while remaining faithful to Matsumae’s original Mega Man tracks. “Crash Man Stage” interpolates synthpop, post-punk guitars, and early 1940s doo-wop; “Heat Man Stage” nods off to duplicated bass tones that would make Daft Punk blush; while the “Air Man Stage” and “Wood Man Stage” themes are 180 BPM frenzies that unfold into illusions of keyboardist Akira Inoue covering Prince’s Controversy. It’s a heady mix, even for an NES release, but it’s also the sign of a music theory student “putting their all into every project”.

To celebrate Mega Man 2’s 35th anniversary, Inverse caught up with Tateishi and Japanese composer Manami Matsumae about the sequel’s legacy, working at Capcom’s Osaka office in the late ‘80s, the process of writing an 8-bit composition, and the evolving importance of creative expression.

Translations provided by Brave Wave Productions’ Mohammed Taher.

Which do you consider to be a more important starting base when it comes to composing video game music: the art, the subject, or the mood?

Manami Matsumae: I believe all three are important. The art helps me feel the movement of the character and the world of the game. The subject lets me understand the purpose for which the game is created and the mood allows me to capture everything, enabling me to compose music that fits the game. So all aspects are crucial.

Takashi Tateishi: I think it's most important to compose music that enhances the player's own experience in the game.

When did you first take an initial interest in writing and recording music?

Tateishi: I started composing simple music around the age of 12 and then I became interested in multitrack recording around the age of 15.

Matsumae: It started after I joined Capcom. Until then, I didn't do any composition or recording; I was solely focused on playing the piano.

With Capcom being a smaller company at the time, what was it like working with the team in the Osaka office? And did your day-to-day life change after the release of Mega Man?

Matsumae: When I was there, Capcom was only a small company with around 200 employees. Our music production department couldn't fit in the main building and we had to rent space in a different building across the street. So there were many people I never worked with directly. After 1987, as Capcom was in a transitional phase with many games in development, my days mostly revolved around commuting between my home and the office.

“Back then, overtime was the norm.”

Tateishi: During my time at Capcom, my main task was to compose and then convert those compositions into game data. Looking back, I remember composing at a very fast pace every day, even compared to the pace of composing in later stages of my life.

Manami-san, how did you first meet Takashi-san?

Matsumae: He joined the company about six months after me as a mid-career hire. He then made a name for himself in the consumer division, while I started working in the arcade division. We were on completely different paths, but I helped him with his music as a sort of break from my own work. It wasn't so much a collaboration of ideas as it was just lending a hand.

Did management approve of sound team members collaborating due to the office’s close workspace arrangements? Or did Capcom’s work culture gradually change over time?

Matsumae: During my time, Capcom was releasing different types of video games to boost its popularity. Therefore, it was common to be working on two or three games simultaneously. I do believe labor standards are more clearly defined now, but back then, overtime was the norm. The work culture at Capcom evolved over time.

With Capcom’s primary focus being arcade games in the late ‘80s and ‘90s, what were the main differences in composing music for an arcade title versus composing for the NES?

Matsumae: The clear difference was in the number of sounds. The Famicom used a chiptune sound source with three tones plus noise, whereas arcade could use an FM sound source with six tones plus one sampling sound.

Tateishi: At the time, I think everyone wanted to work on arcade games because the number and variety of sounds available were overwhelmingly more in arcades.

“Understanding the hardware was necessary to compose better music with limited data.”

What was the process like in composing an 8-bit song for the NES?

Matsumae: First, I created the music using a composition tool, then I converted the notes into numbers to input them into the ROM and created and programmed the tones myself. Since NES music was often short due to storage limitations, it only took a few hours to input and program a single song.

Tateishi: Composing an 8-bit song for the NES was very challenging due to the constraints. It wasn't just about musical talent; understanding the hardware was necessary to compose better music with limited data. It took at least four hours to convert a song into notes to be compatible with the hardware.

Why do you think video game composers aren’t as famous in Japan compared to the US?

Matsumae: I think it's because of the different ways video games are sold. In the past, strategies differed depending on whether games were sold internationally or just domestically. Now, with Capcom's popular titles like Resident Evil and Monster Hunter being famous overseas, there are a lot more opportunities for others to hear their music. People might wonder who composed the music and look them up, leading to fame. However, this doesn't apply to all video games; only certain composers for specific games are becoming famous.

Is there a specific character or series you would still like to write music for?

Matsumae: I've been composing game music for over 35 years. I believe I have the ability to adapt to any game genre, so I don't focus on specific titles. If I receive a job offer, I'll just compose it without much fuss (laughs).

Takashi-san, have you had thoughts of composing video game music in the future?

Tateishi: I haven't thought about it. I have completely stopped composing now. For the rest of my life, I plan to live as a business executive.

Do you have a favorite Mega Man 2 cover or remix of recent memory?

Tateishi: A great version that I found popular on the Japanese internet is the JAM Project's live performance of “Omoide wa Okkusenman”.

What advice would you give to a music composer who is interested in video games?

Matsumae: In video games, there are various scenes so you have to write music that fits each one. I think it's good to listen to different genres of music and stock them in your mind. This makes it easier to imagine music that fits a certain atmosphere.

Tateishi: The ways to express music are limitless. Continue to create the music you want to make without hesitation.