It’s nearly impossible to determine the highlight of Fred Olen Ray’s exhausting filmography. The prolific B-movie maestro, inadvertently responsible for kickstarting Quentin Tarantino’s career, has racked up more than 200 credits as a producer, writer, and director since the early 1970s. But 1988’s Deep Space must be a prime contender.

Arriving the same year Ray brought an army of power tool-obsessed Egyptian prostitutes to the screen (Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers) and sent David Carradine on a wife-rescuing mission with only a disgusting, disembodied head for company (Warlords), its tale of a genetically-engineered monster causing havoc across Los Angeles appears relatively conventional in comparison. Yet the sci-fi horror, which began as a follow-up to 1985’s Creature, still contains enough idiosyncrasies to set the WTF gauge off the scale.

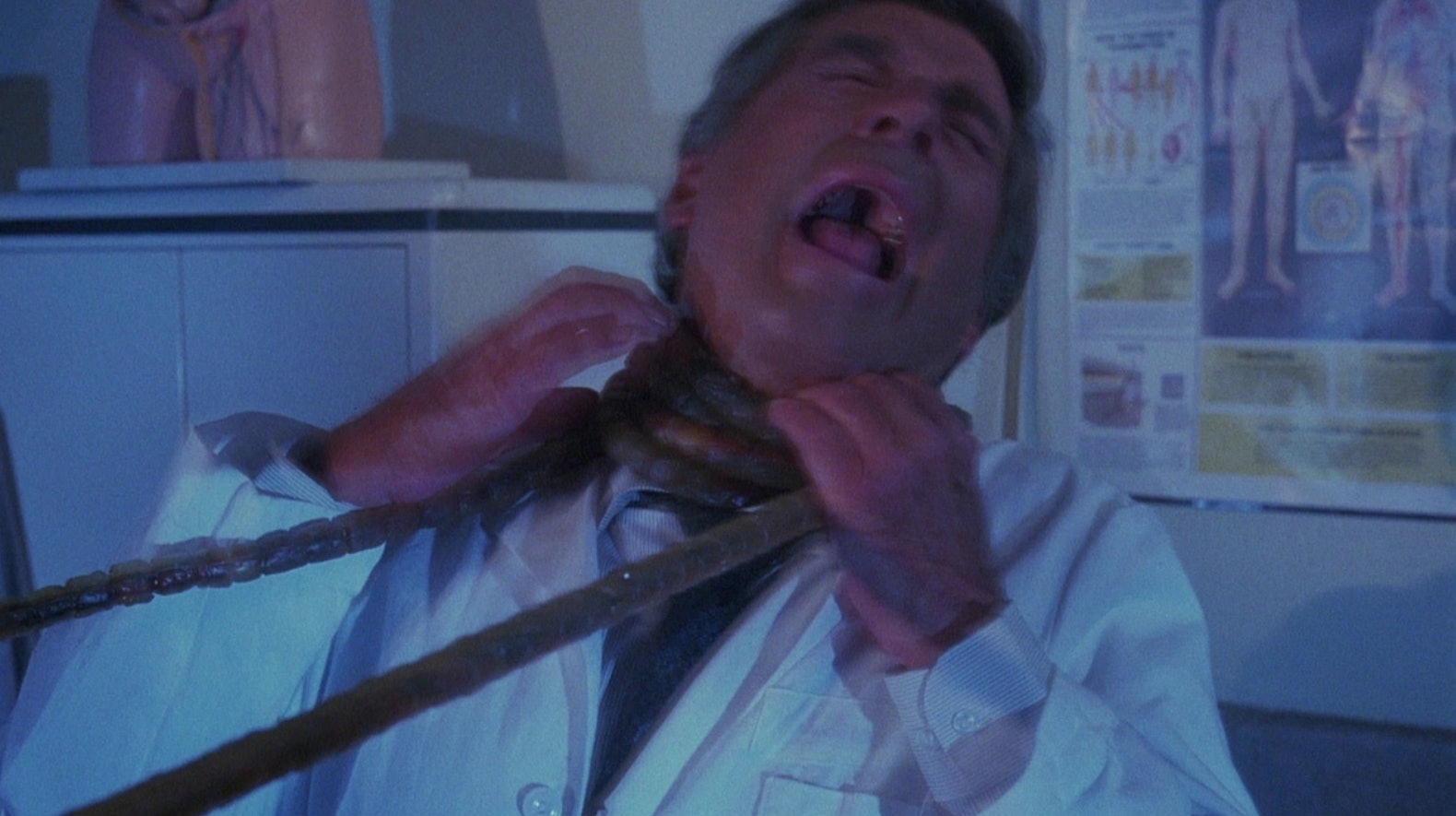

The chaos begins when a government satellite storing said mutant crashes spectacularly in an airfield, in the only scene with any relevance to the title and intergalactic artwork. While investigating the wreckage, a teenage couple in the middle of a domestic dispute discovers that not only is there a survivor, it has a fondness for wrapping its gross intestinal-like tentacles around human heads.

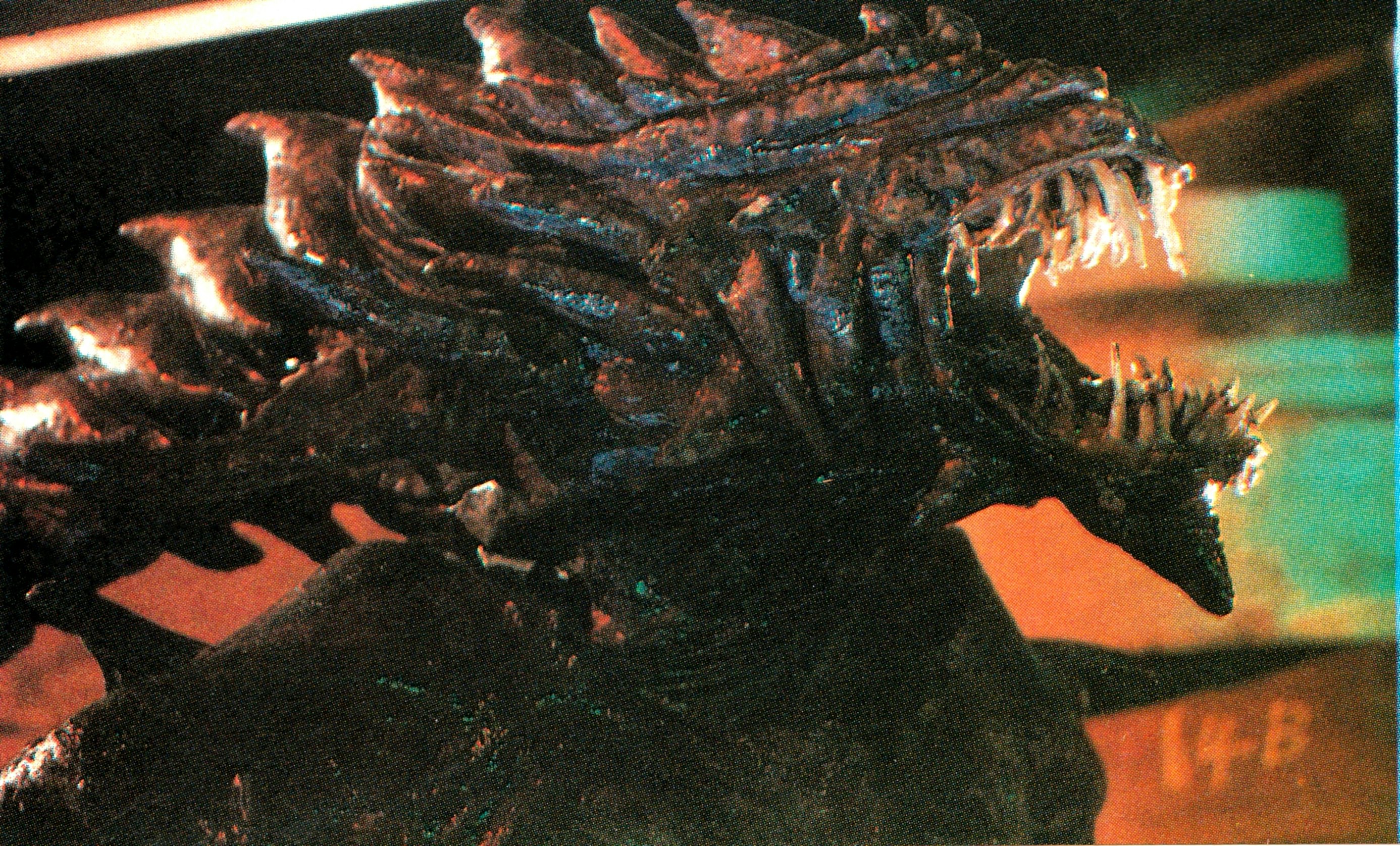

Reportedly given more money than ever by the famously low-budget Trans World Entertainment, Ray was able to present a relatively convincing monster. Metamorphosizing from a sentient slab of rock to a hideous amalgamation of slimy limbs, razor-sharp fangs, and protruding spikes, the unnamed beast is a blatant Xenomorph rip-off (look out for the carbon copies of Alien’s cat scene and iconic chest-burster). Yet unlike many of the studio’s creature features, it could still scare the pants off any youngsters who’d sneakily rented a copy.

The beast, who later births a couple of equally murderous critters, is initially contained in a lab before killing two scientists and, despite its gargantuan size, escaping into the streets without anyone noticing. It’s also a selective killer, heading straight for the poor drunk who witnessed its fireball arrival. In fact, its body count is restricted to those who are either responsible for, or already aware of, its existence.

But Deep Space has more to offer than its eyeless, elongated villain. No doubt taking its cue from the recent success of the first Lethal Weapon, it also boasts a charismatic buddy cop duo in the shape of womanizing detective Ian McLemore (Charles Napier) and wisecracking partner Jerry Merris (Firefly’s Ron Glass).

McLemore is a particularly engaging character who sits somewhere between the “doesn’t play by the rules” cockiness of Mel Gibson’s Riggs and the hapless antics of The Naked Gun’s Lieutenant Frank Drebin. At one point, he manages to prevent a baby alien from devouring a scientist, only to throw the gelatinous blob onto the face of his love interest cop Carla (Ann Turkel). Then in one of the film’s several zingers, McLemore is asked whether the rock is extraterrestrial, responding, “No man, it’s from outer space!"

This is a film with its tongue placed firmly in cheek. Who knew aliens needed to be read their Miranda rights? In another nod to Ellen Ripley’s escapades, the slobbering alien sidles up aside McLemore and, for a few seconds, is hilariously unaware. And then there’s the seduction scene, one of the most bizarre ever committed to celluloid. In an attempt to woo Carla, McLemore changes into a kilt before showing off his skills on the bagpipes. “It’s supposed to make you take your clothes off,” he says. “It’s the only way to stop me playing.” Remarkably, it works.

Sadly, getting turned on by the sound of Scotland’s national woodwind is all Turkel has to do. This being the 1980s, her female cop has to let the men be the heroes. In the climactic scene, set in a dim, smoke-filled warehouse that looks primed for a hair metal video, Carla is relegated to both damsel-in-distress and incompetent klutz; at a vital moment, she drops a chainsaw that nearly slices McLemore’s most sensitive area.

You could argue, however, that it’s another woman who saves the day, even though she never leaves her room. Camping it up as a psychic who can somehow envision the monster’s whereabouts, screen legend Julie Newmar nearly steals the show with a few phone call warnings that largely fall on deaf ears. “Last night, something came from the stars,” she tells an uninterested cop in the breathless style of Marilyn Monroe. “Something more terrible than death itself.”

Deep Space didn’t need quite as many tête-à-têtes between our two intrepid cops and their chief (Bo Svenson), or the constant squabbling between the men of science and the men in power. There are also plot holes and leaps in logic galore; one victim brings their demise on themselves by unfathomably bringing a piece of the killer alien rock marked as evidence home with them. Still, this doesn’t detract too much from a film that, although misleadingly marketed, is ’80s horror at its schlocky best.