Conventional wisdom dictates that a well-written song will stand up even when reduced to simple chords on acoustic guitar. But at some point, we’ve all heard songs in which complex or unusual chord voicings form an integral part of the harmony.

Alternatively, both these approaches might co-exist within the same song – namely, regular major and minor chords overdubbed with a layer of more unusual or extended voicings. This can sound particularly appealing when played on two acoustics, panned left and right, to form a stereo spread.

As players it’s worth having some of these chords at our disposal to further broaden our own musical horizons. A solid knowledge of some expansive chords that can take you beyond regular major and minor shapes is a must for any player, and can help facilitate greater experimentation with compositions, aid the rearranging old tunes, or just help you get to know the fretboard on a deeper level.

The following chords will give you food for thought and help you do just that. Every key is represented, with a major and a minor chord for each. Also included within the 30 are six ‘bonus’ chords, for which there are no particular criteria, apart from sounding nice!

The possibilities are virtually inexhaustible, so these examples should just act as your starting point. And the good news is that there are always more weird and wonderful chords to be found.

Some of the examples provided below are movable to any key/position on the fretboard, but since we’re concentrating on acoustic guitar here, I’ve decided to lean towards ringing open strings, making many of these unique to one position. In these cases, a capo and/or the willingness to experiment with alternative tunings is very useful.

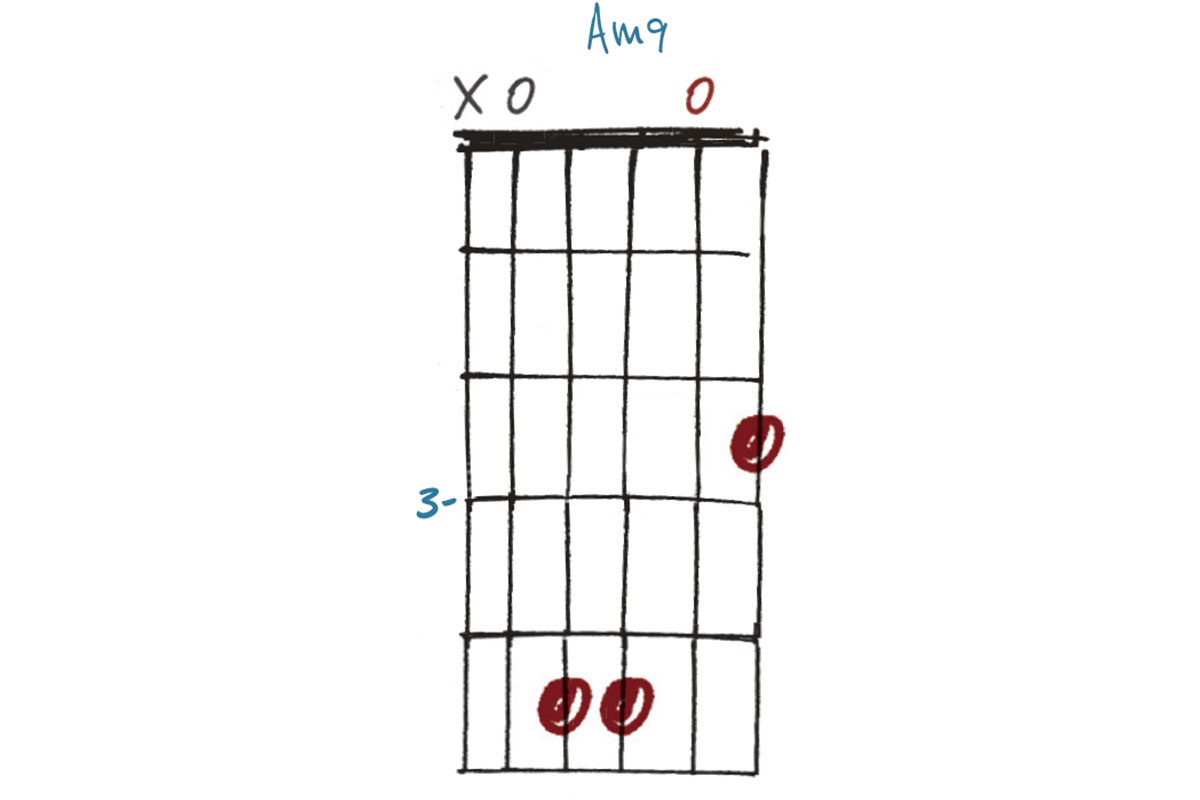

Example 1. A minor 9

This A minor 9 makes use of the jangling open second string (which gives our 9th, B). The semitone interval to the C fretted on the adjacent third string also adds a nice dissonance. Shapes such as this aren’t generally movable, but it’s always worth a try – check out Example 2.

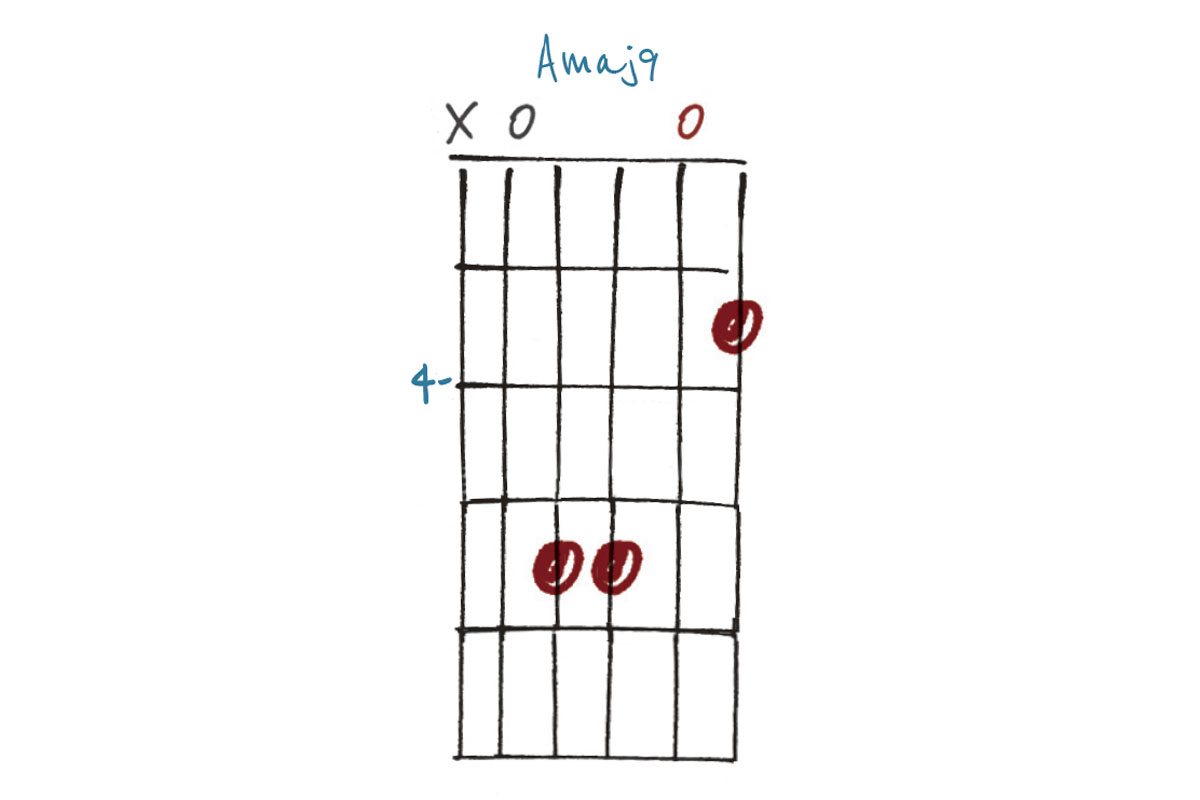

Example 2. Amaj9

Moving the shape from Example 1 up a semitone/fret gives us this A major 9. The term ‘major’ here refers to the major 7th (G#) found on the fourth and first strings. The 9th (B) is the open second string as before – its relationship to the fretted notes remains the same in this instance.

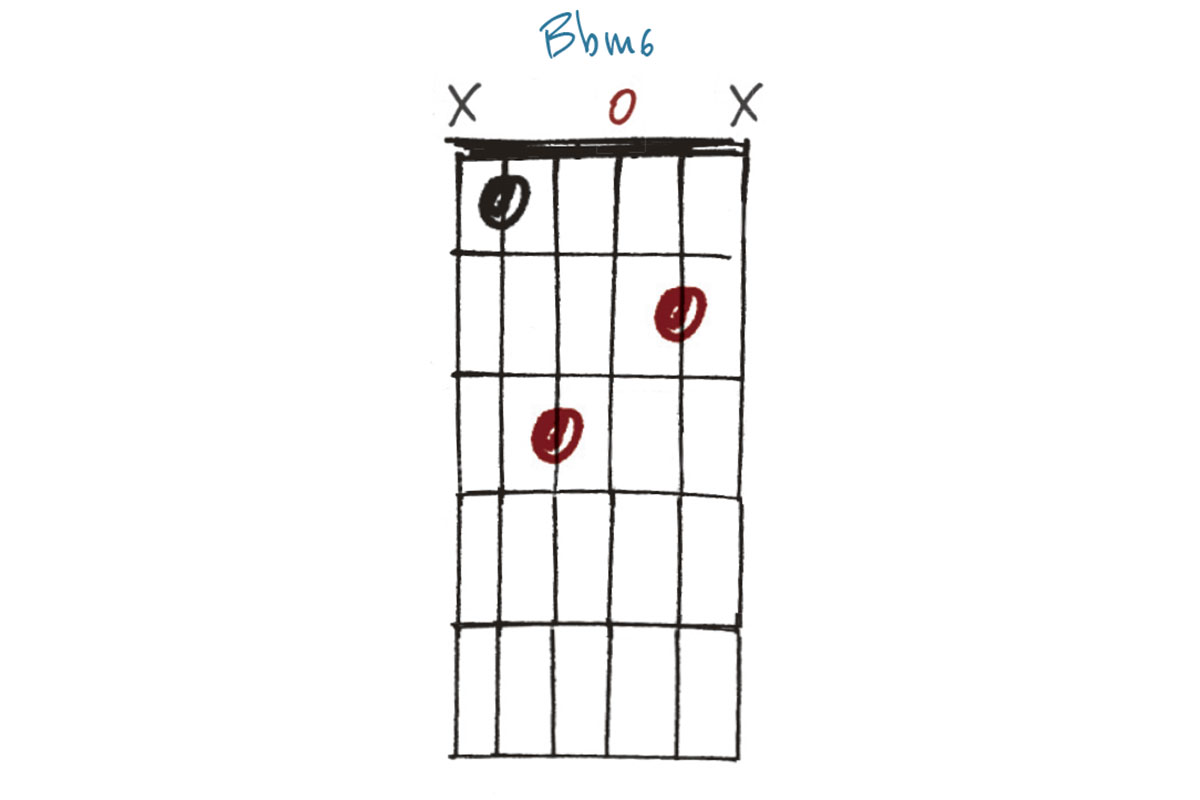

Example 3. Bb minor 6

You’ll need to mute the first and sixth strings carefully on this Bb minor 6 – unless you’re looking for a particularly jarring chord! The open third string gives us the 6th (G), which combines with the fretted notes of the Bb minor triad to give the name. If only naming chords could always be this simple!

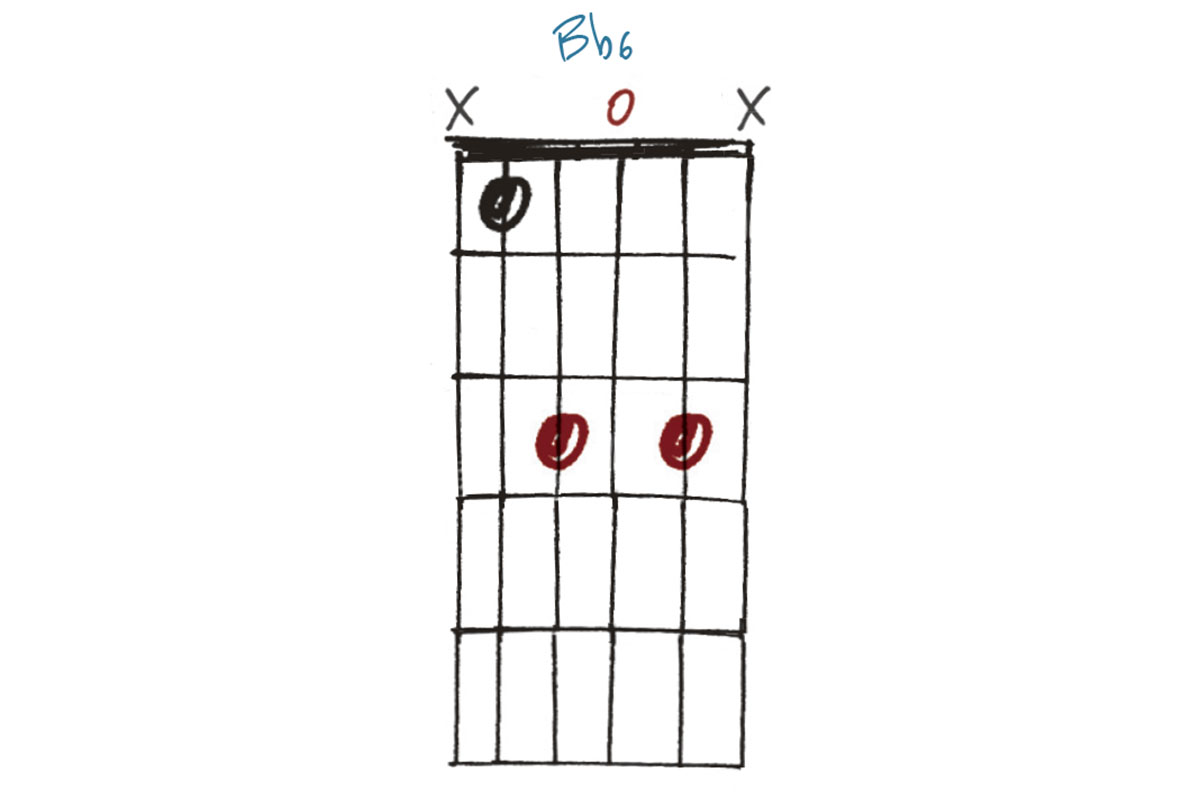

Example 4. Bb6

The same basic idea as Example 3 but with the minor 3rd (Db) being moved up a semitone/fret on the second string to give us a D, for a Bb6 chord. The open third string still functions as the 6th. This makes for an interesting movable chord, with the open G acting like a ‘drone’ in various positions.

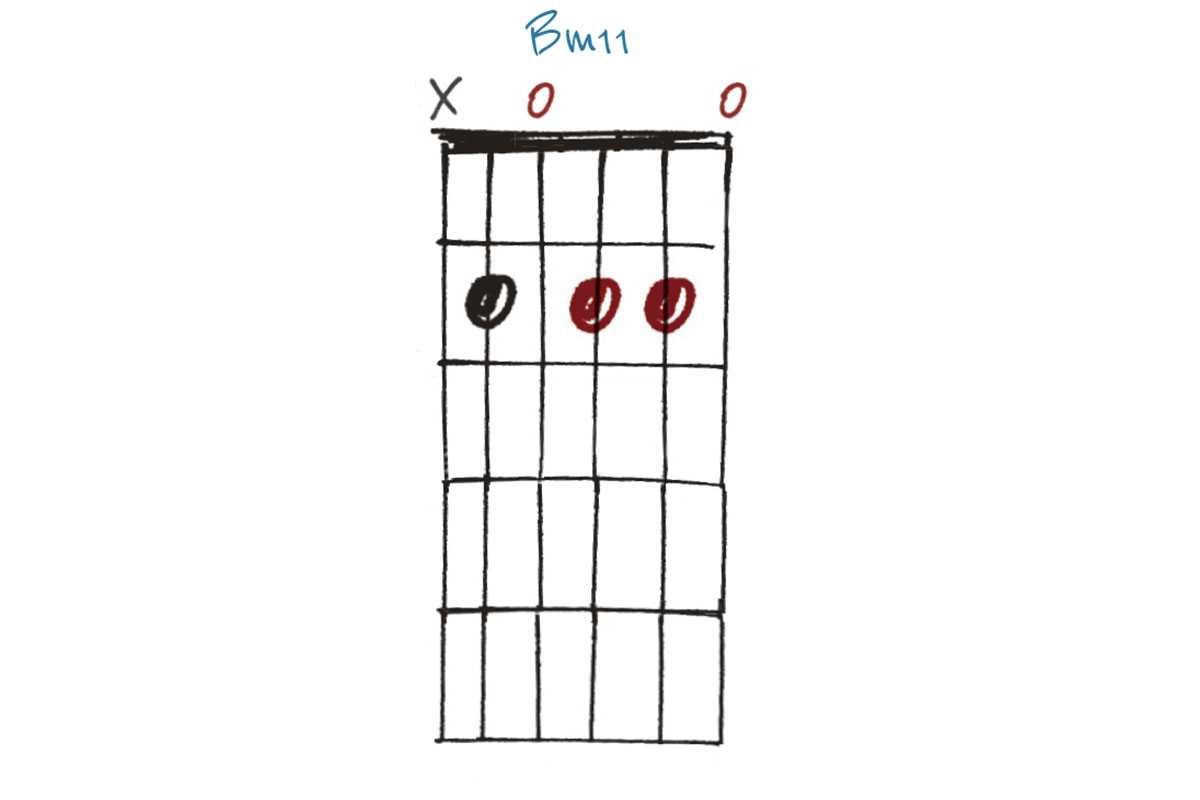

Example 5. Bm11

This B minor 11 is an extended minor chord but could also be viewed as ‘polychord’ – part B minor and part A major. It has an A triad on the third, second and first strings over a B root on the fifth string and its minor 3rd (D) is on the open fourth string.

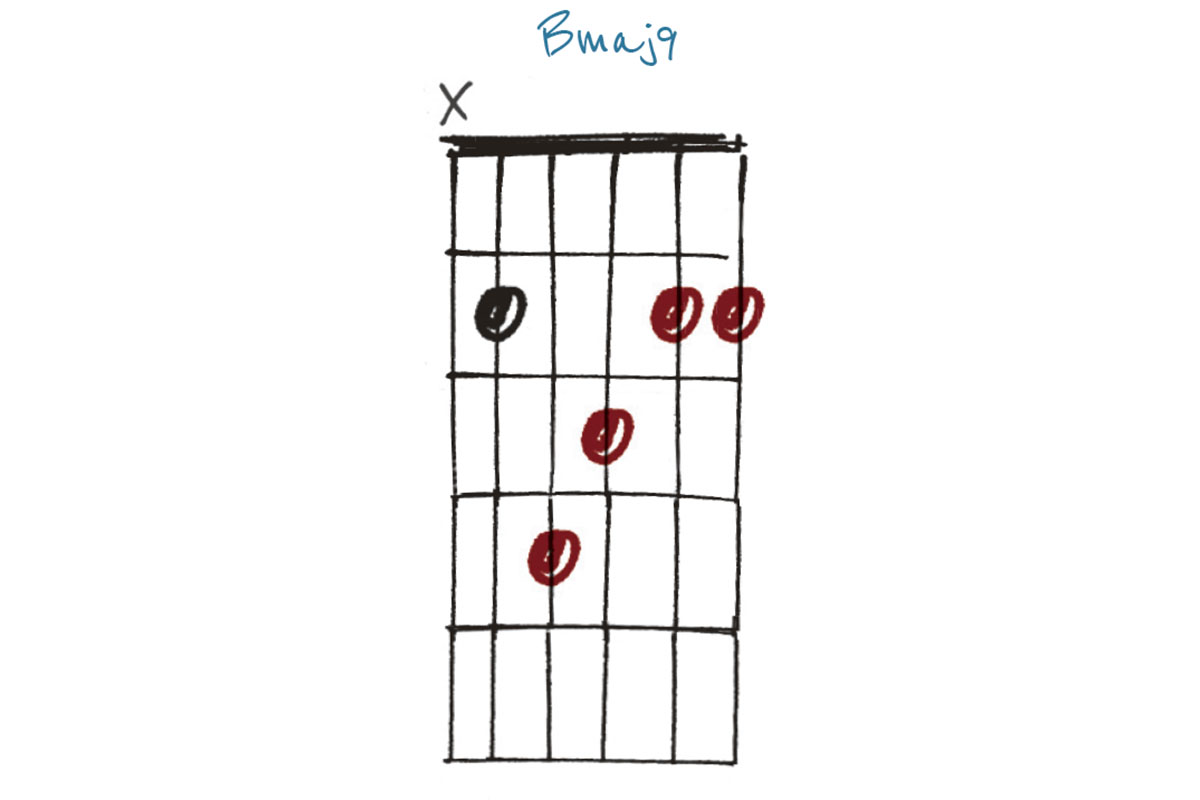

Example 6. Bmaj9

This B major 9 is a barre chord and so can be moved to any position or key with its intervallic structure undisturbed. Continuing with the concept of polychords from Example 5, in an overdubbing scenario you could view this as an F# major chord over a B bass note.

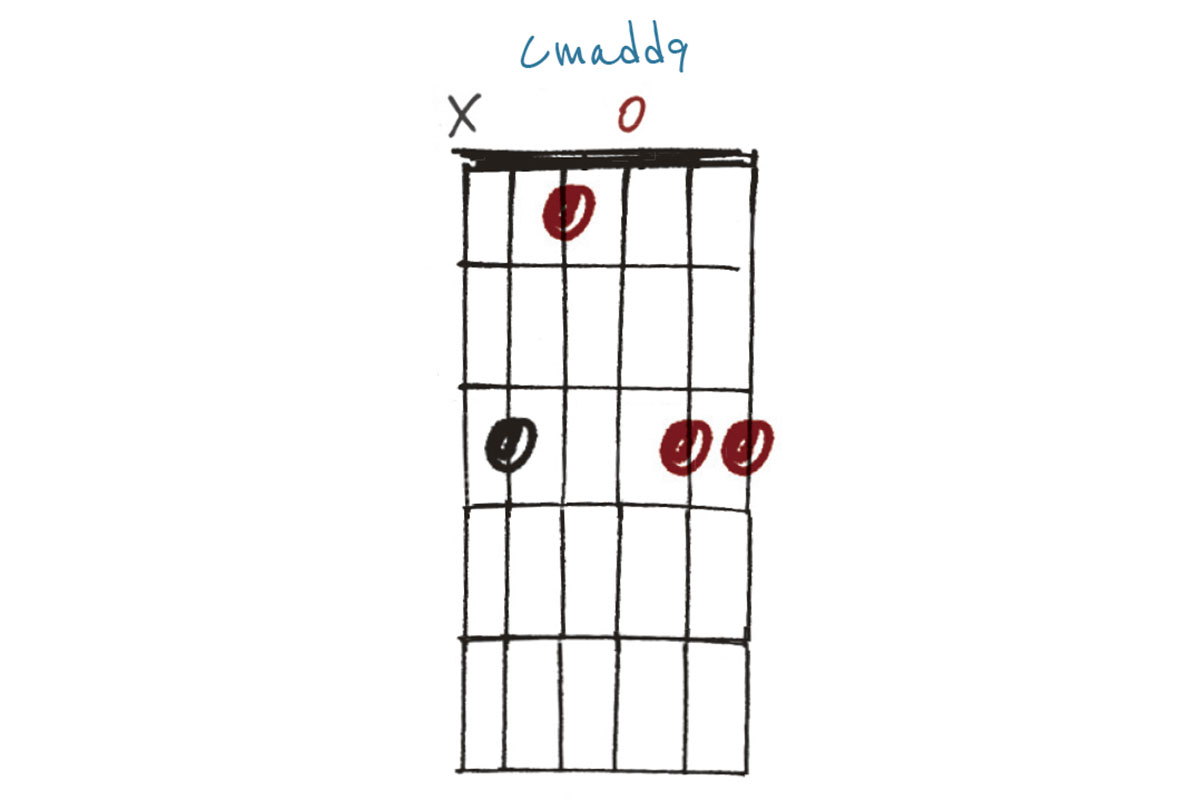

Example 7. Cmadd9

This C minor add 9 allows you to create harmonic complexity using regular open-position chords. This is very useful if you’re creating a track bed using strummed open acoustic chords and want to keep consistency, which can be lost when jumping between open and fretted positions. A little bit of a stretch at first, but it gets easier!

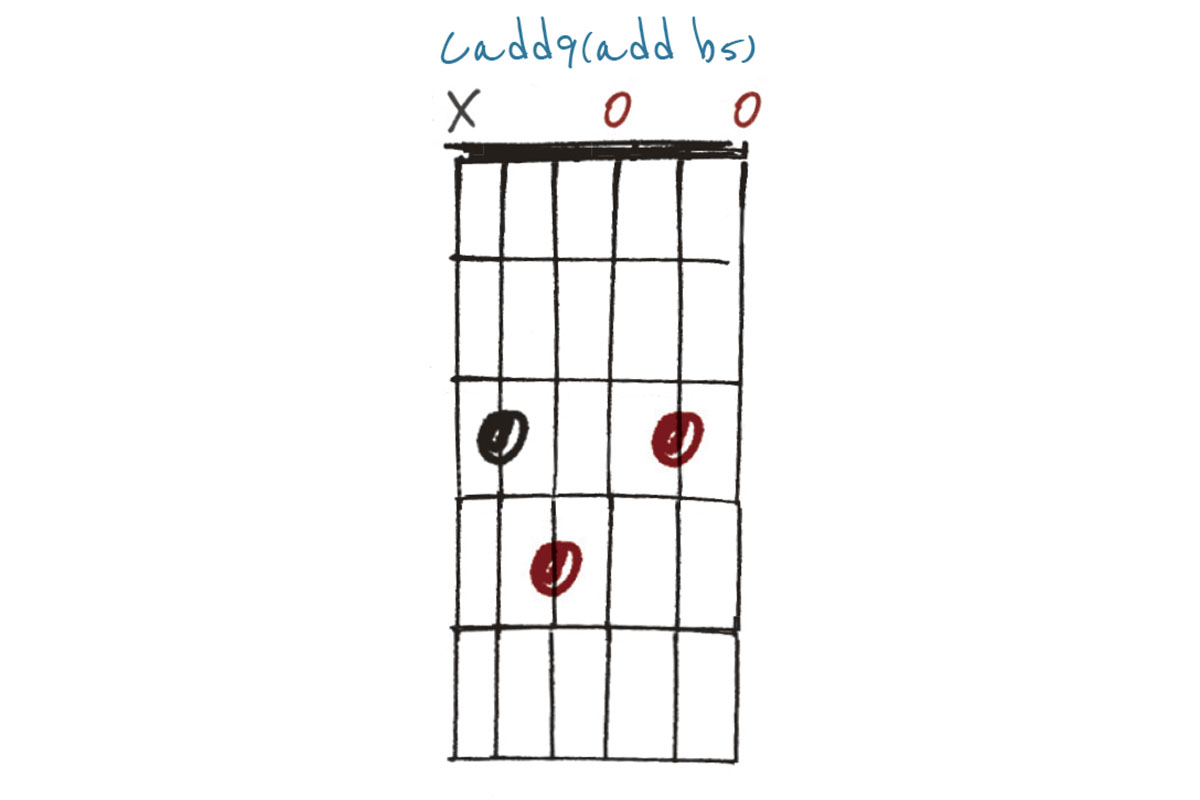

Example 8. C add9(add b5)

This C add9(add b5) demonstrates that a chord doesn’t have to be hard to play to have a complicated name! This is particularly good for fingerstyle playing where a regular C major sounds too ‘ordinary’. The add9 (D) appears on the second string, with the b5 (Gb) on the fourth string.

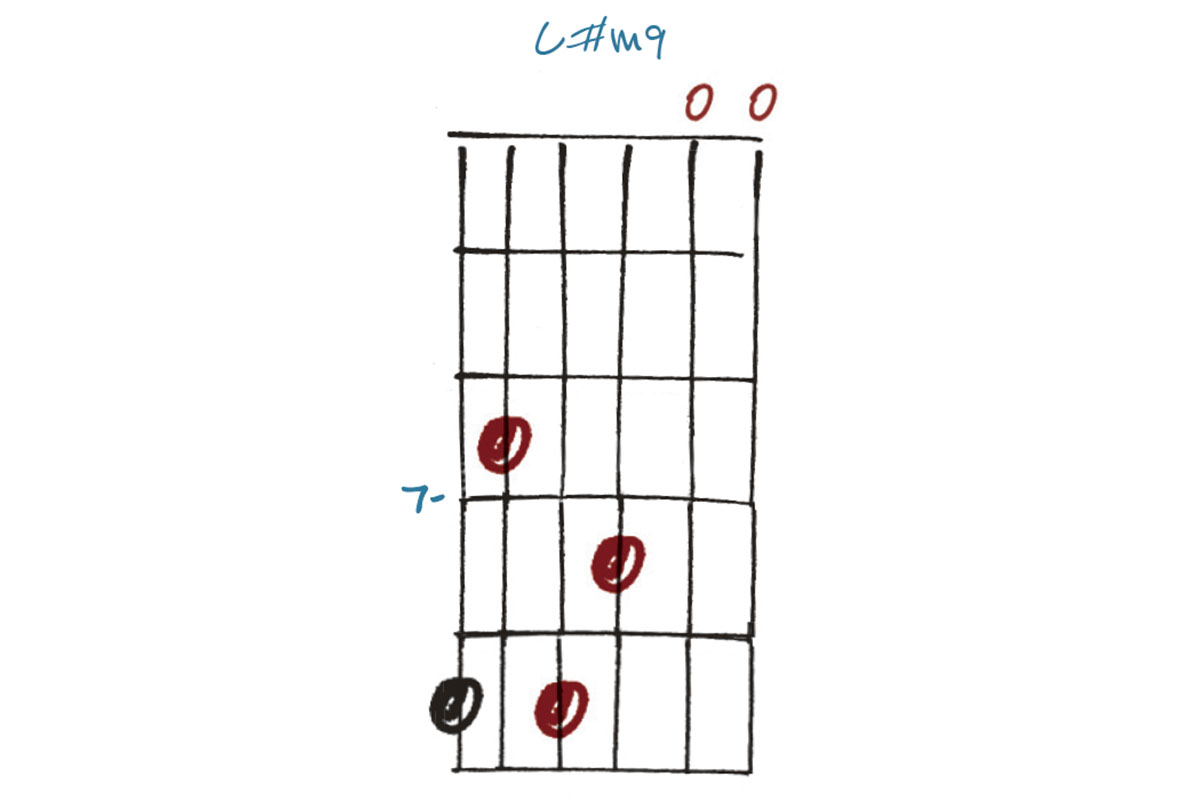

Example 9. C#m9

This C# minor 9 combines fretted and open strings, using all six to make this a great chord for strumming. This is another one worth moving to different positions for some nice surprises. The intervallic relationships will change with each move, but it can be fun to work these out.

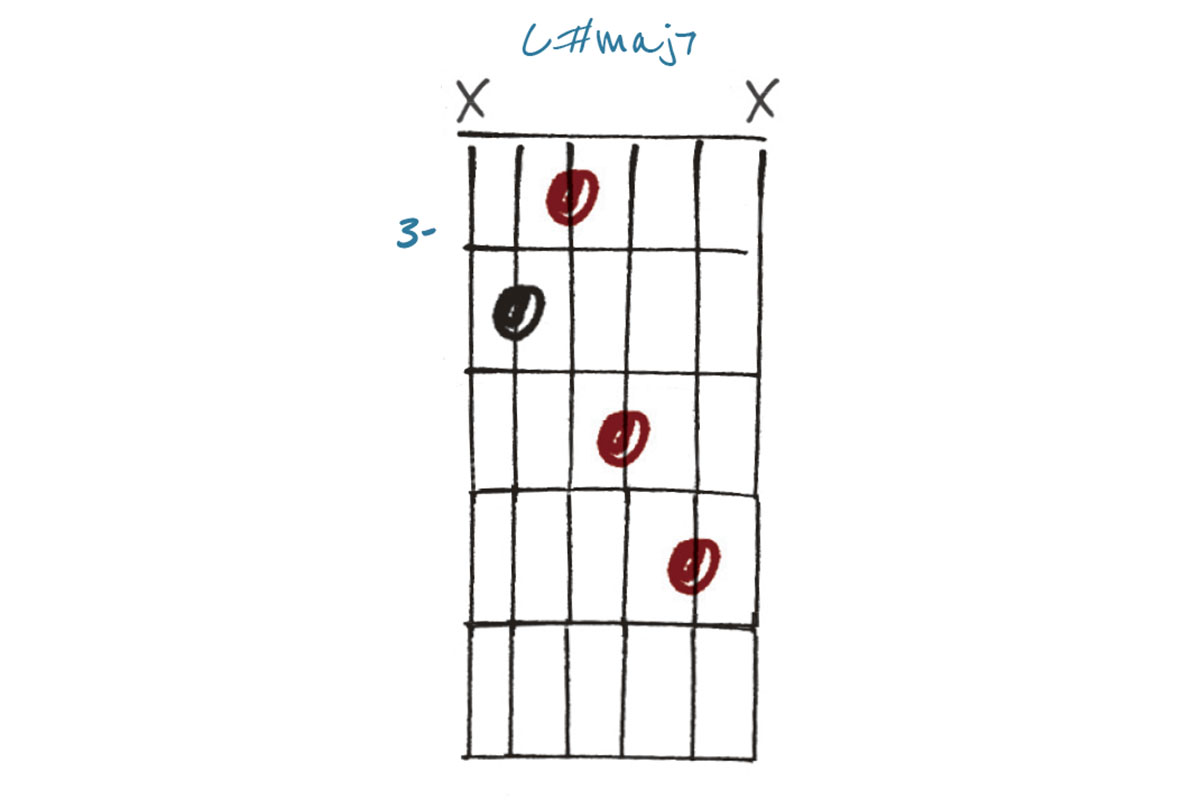

Example 10. C#maj7

This C# major 7 doesn’t use any open strings, but what you lose in open string ‘jangle’ you gain in movability. You may notice that the 5th (G#) is absent; this is a commonly used device in jazz chords. In comparison, a C# major 7 with a 5th sounds more ‘rock and pop’.

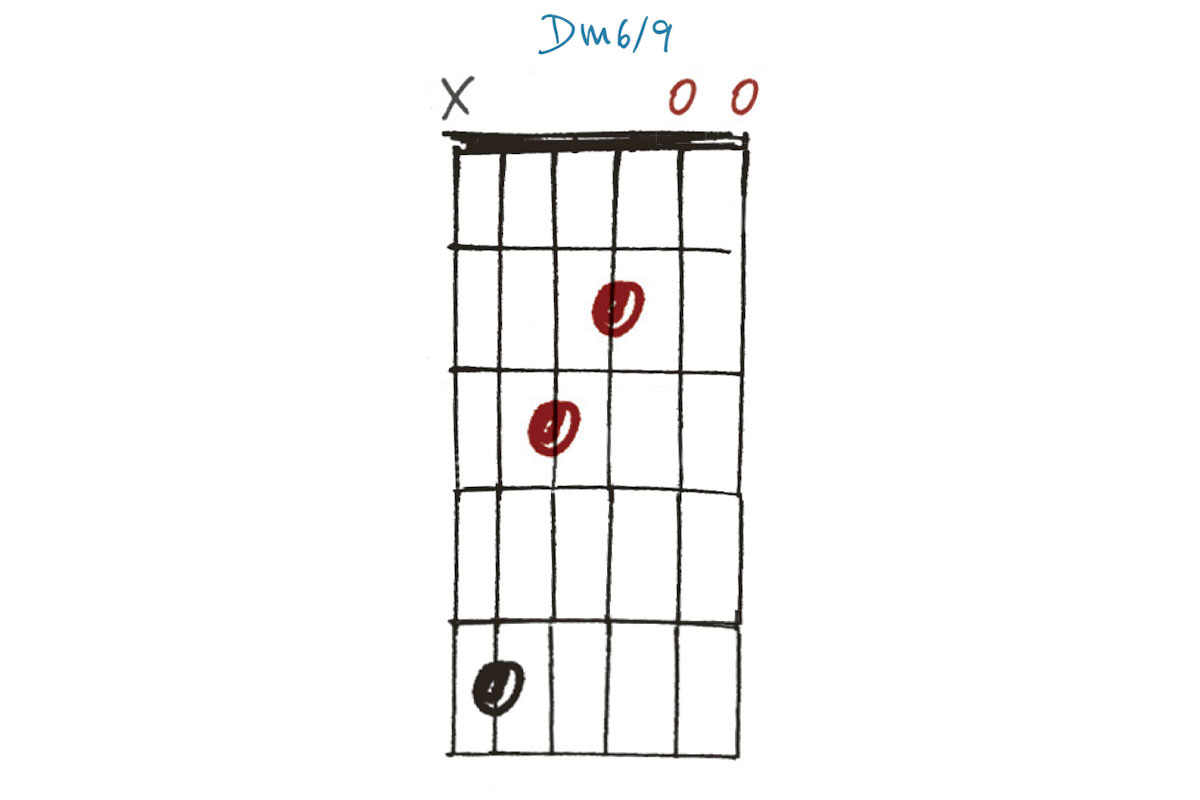

Example 11. Dm6/9

Playing a D minor triad on the fifth, fourth and third strings (D F A, in that order) and combining this with the open second string (B) gives us a 6th and the first (E) gives us a 9th. Technically, this is a D minor 6 (add9), but most chord charts will abbreviate this to D minor 6/9.

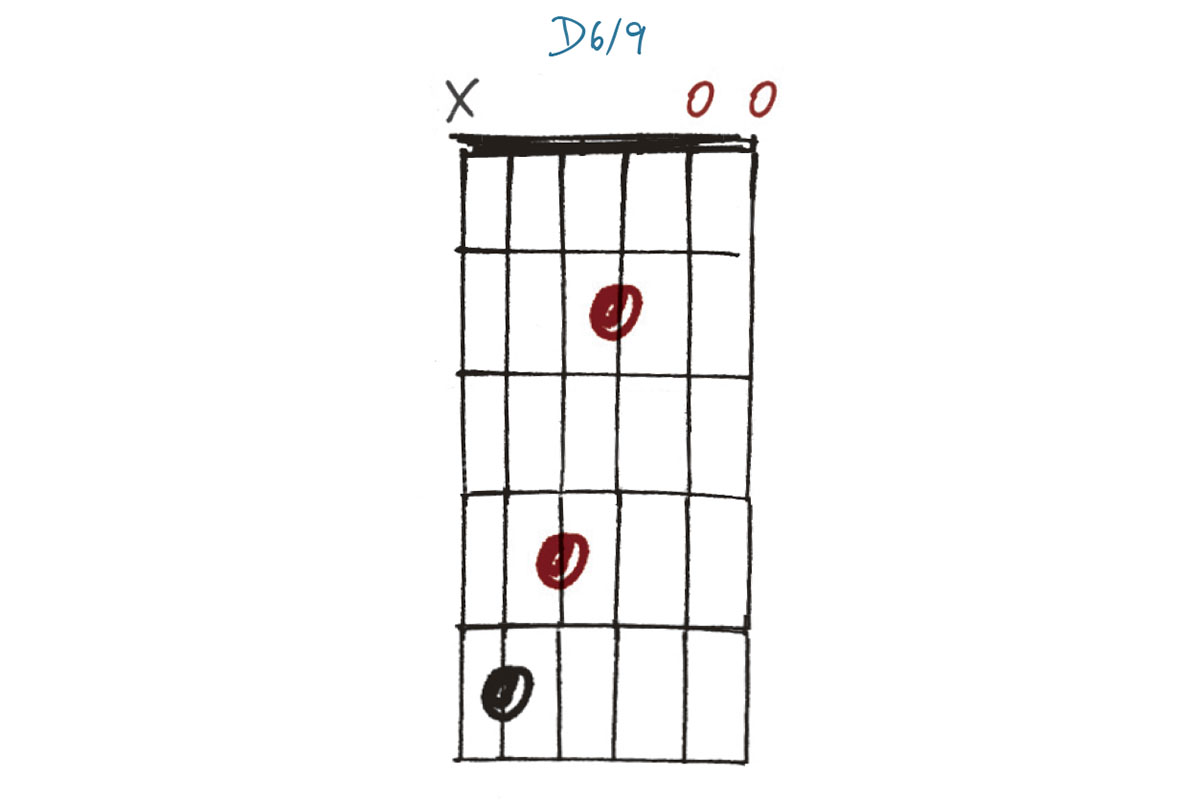

Example 12. D6/9

As Example 11 but changing to a major 3rd (F#) on the fourth string, this gives a very different sound and mood. The naming convention remains the same: D6 (add9) shortened to D6/9. A bit of a handful but great for preserving that ‘open-string sound’ when combined with some of the other ideas here.

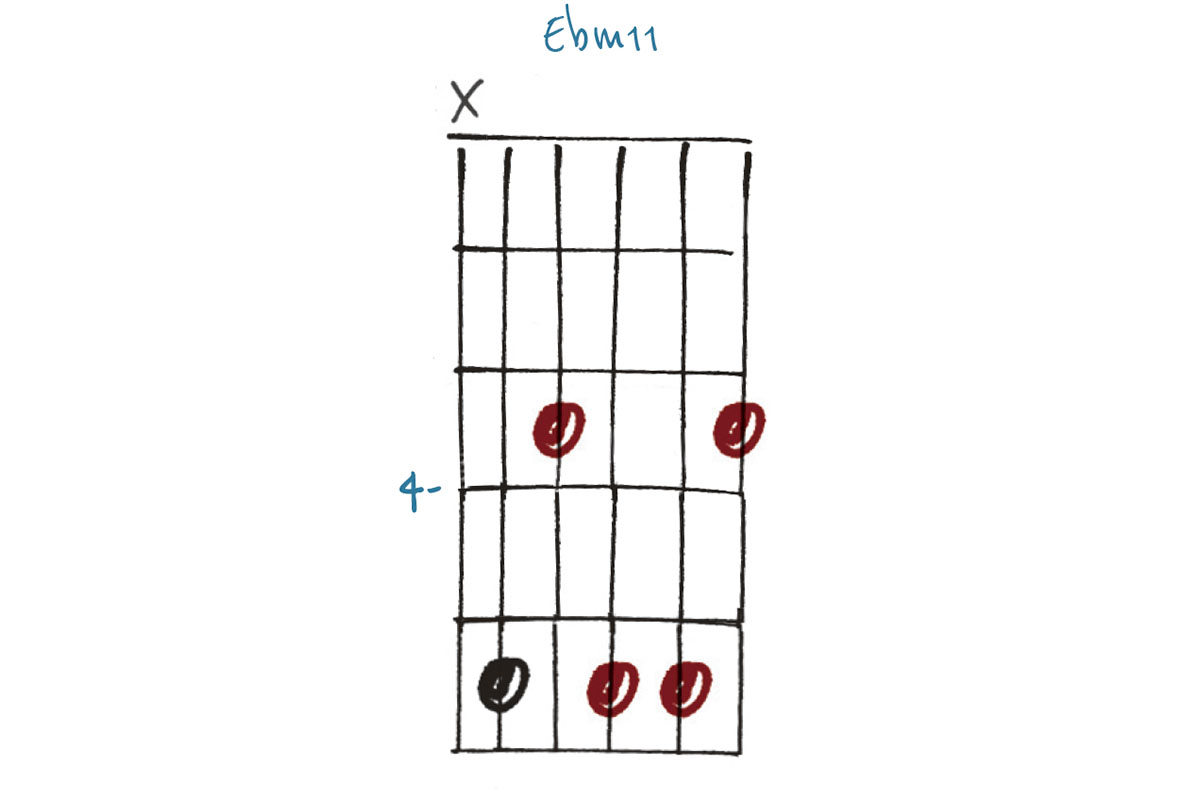

Example 13. Ebm11

This Eb minor 11 chord has its root on the fifth string, then ascending we find the minor 3rd (Gb), b7 (Db) and 9th (F) in that order. What differentiates this from an Eb minor 9 chord is the 11th (Ab) on the first string. Note the complete Db triad hiding in plain sight here!

Example 14. Ebmaj7

This voicing of Eb major 7 doesn’t have a lot going on in the bass but is useful for keeping consistency with other open chords. In a band context, fingerstyle or alongside another guitar using regular voicings, the lack of bass notes wouldn’t matter.

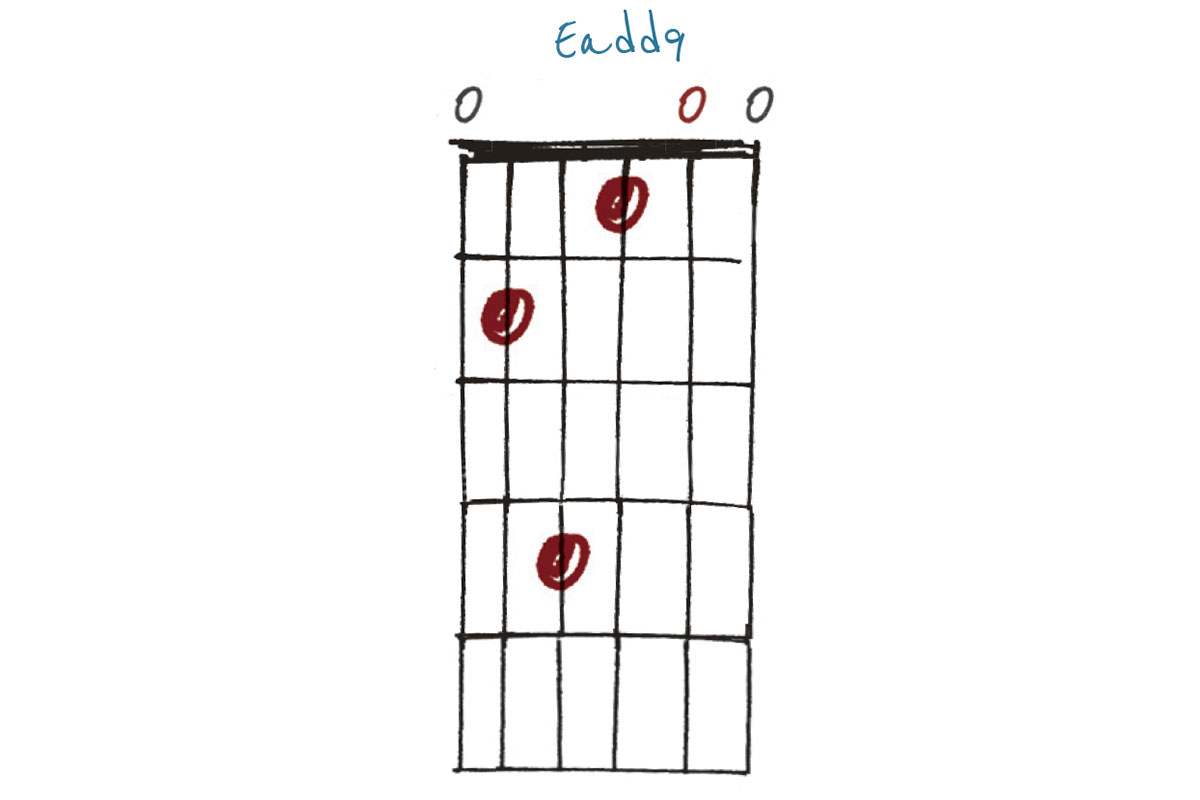

Example 15. Emadd9

This E minor add9 is a frequently used chord but manages to avoid sounding hackneyed – and it really suits the acoustic guitar. Try moving it around for some other pleasing options, both strumming and fingerpicking.

Example 16. Eadd9

The major counterpart to Example 15, this E add9 features the major 3rd (G#) on the third string. Like Example 15, this can also be moved around the fretboard, albeit to a slightly lesser extent, giving some very pleasant and sometimes unusual alternatives.

Example 17. Fm9

Not an open chord but using all six strings for a ‘wide’ sound, this F minor 9 manages to retain enough ‘jangle’ to sit among more open chords. Removing the G (9th) from the first string gives us F minor 7 as an alternative.

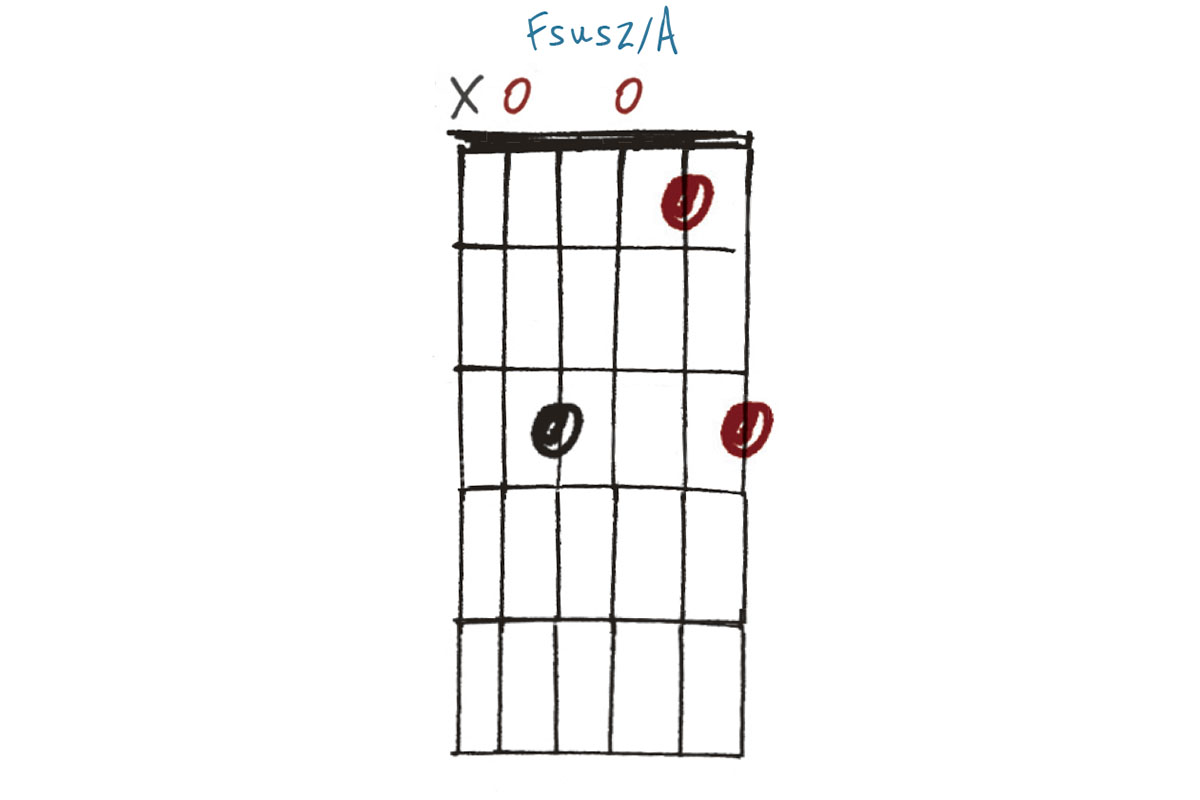

Example 18. Fsus2/A

If you don’t enjoy playing the full F barre chord (and this isn’t uncommon!), why not try this F sus2/A? It won’t work in every situation, but if you can do without the A at the bottom, it becomes more versatile – and can be moved around with some nice results.

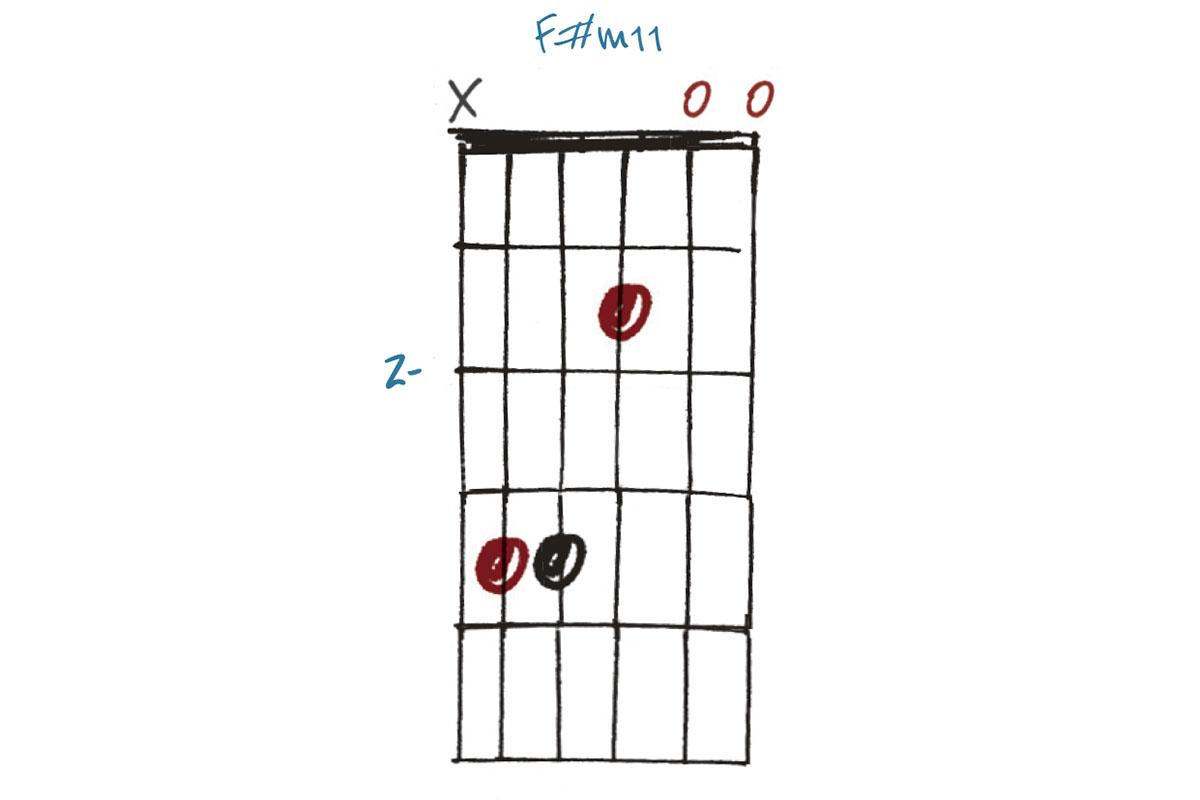

Example 19. F#m11

If your fretting-hand thumb is flexible enough, you can add the root to this F# minor 11 at the 2nd fret of the sixth string. It still sounds nice as it is, though, and will sound very full against a band mix or a regular F#m on another guitar.

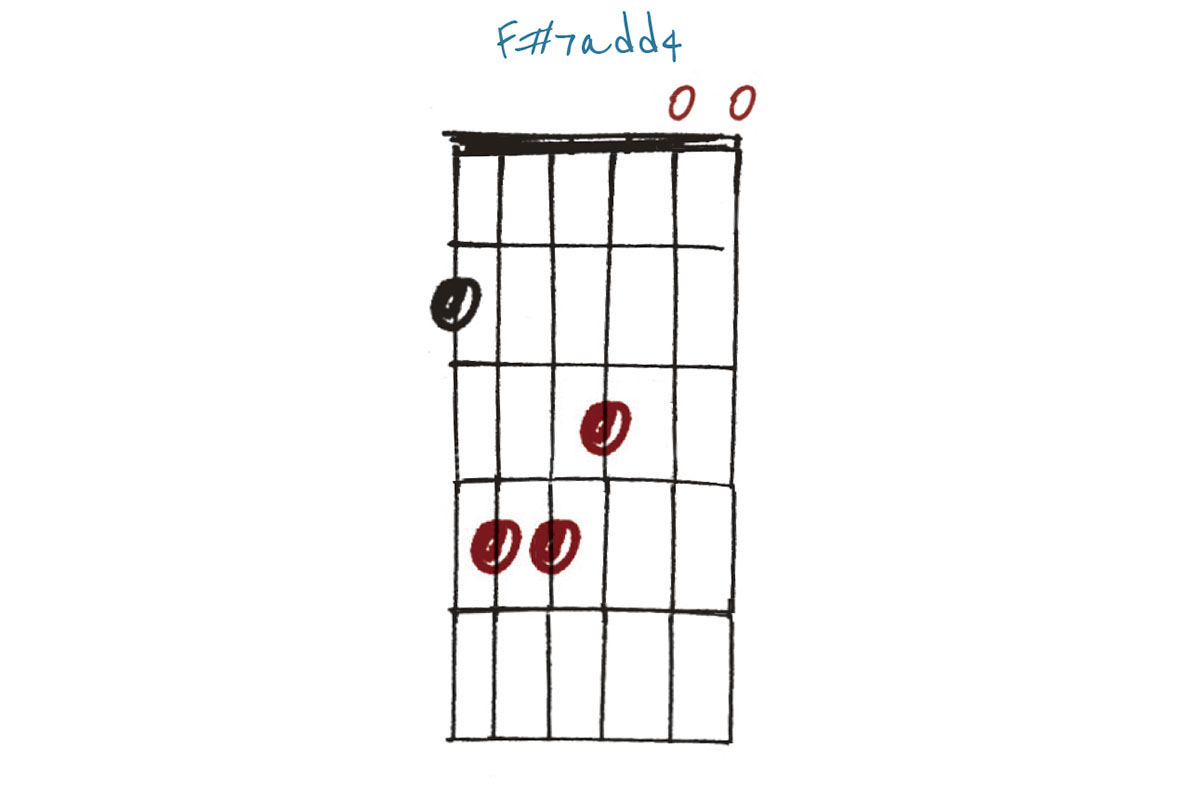

Example 20. F#7add4

Most associated with Alex Lifeson of Rush fame, this F#7 add4 makes a great ringing acoustic chord and, as Alex would certainly tell you, can be moved around the fretboard to good effect, offering an interesting alternative to more than one barre chord.

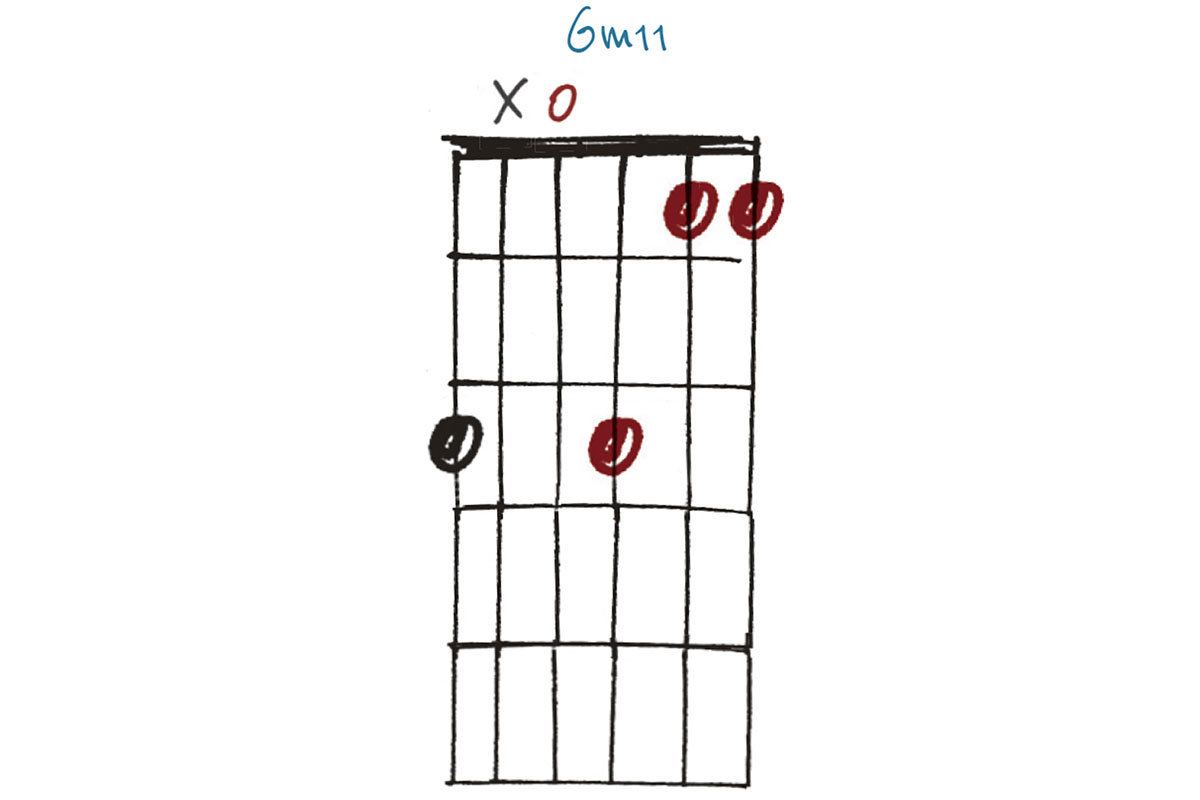

Example 21. Gm11

Some chords can only be strummed with careful muting in place, and this G minor 11 is one such example. A nice alternative or overdub to a regular G minor/G minor 7, this can also be moved to one or two places for some interesting sounds according to taste.

Example 22. Gmaj7

This G major 7 doubles up on the maj7th (F#), featuring it on both the fourth and first strings. For a less harmonically dense alternative, try leaving the fourth string open for a more ‘Eagles’ vibe. Like Example 21, the fifth string is muted.

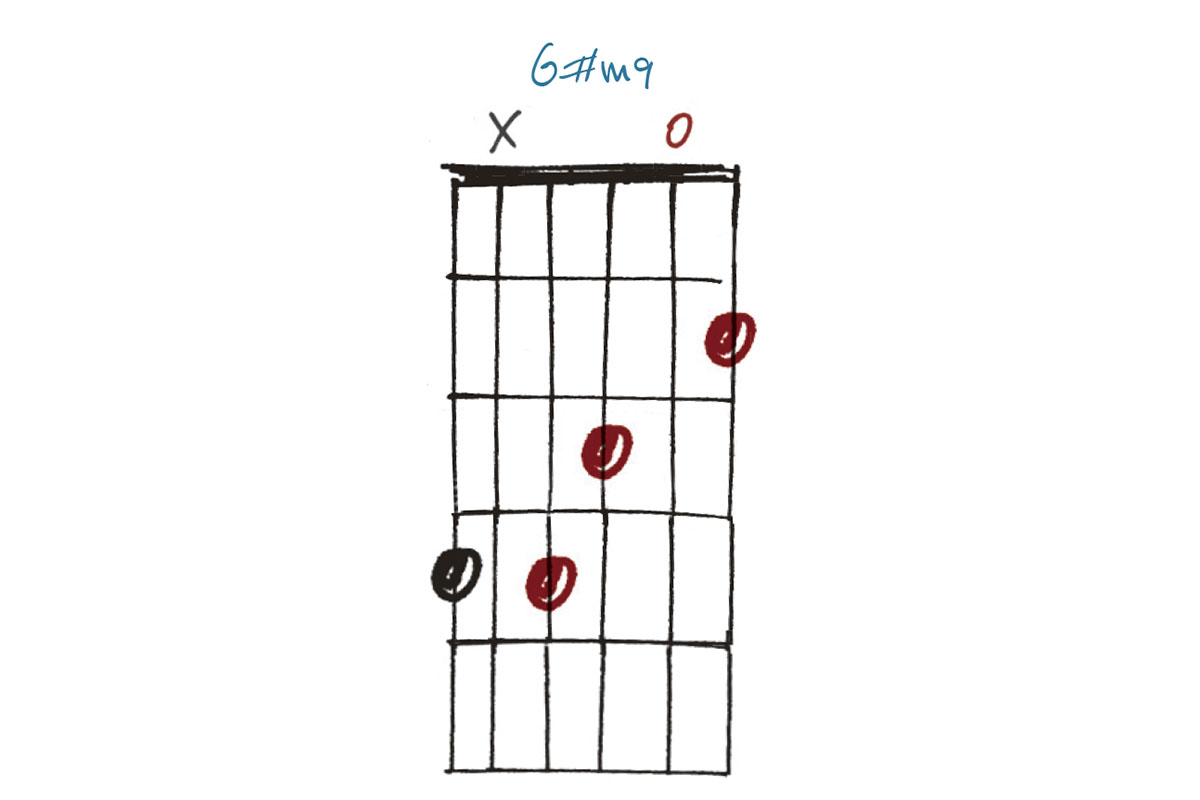

Example 23. G#m9

Keeping that fifth string muted, this G# minor 9 gives a ringing, open alternative to what would otherwise be an uncomfortable barre chord. By moving this around to different positions, you can conjure up various Steve Howe or even Joni Mitchell vibes.

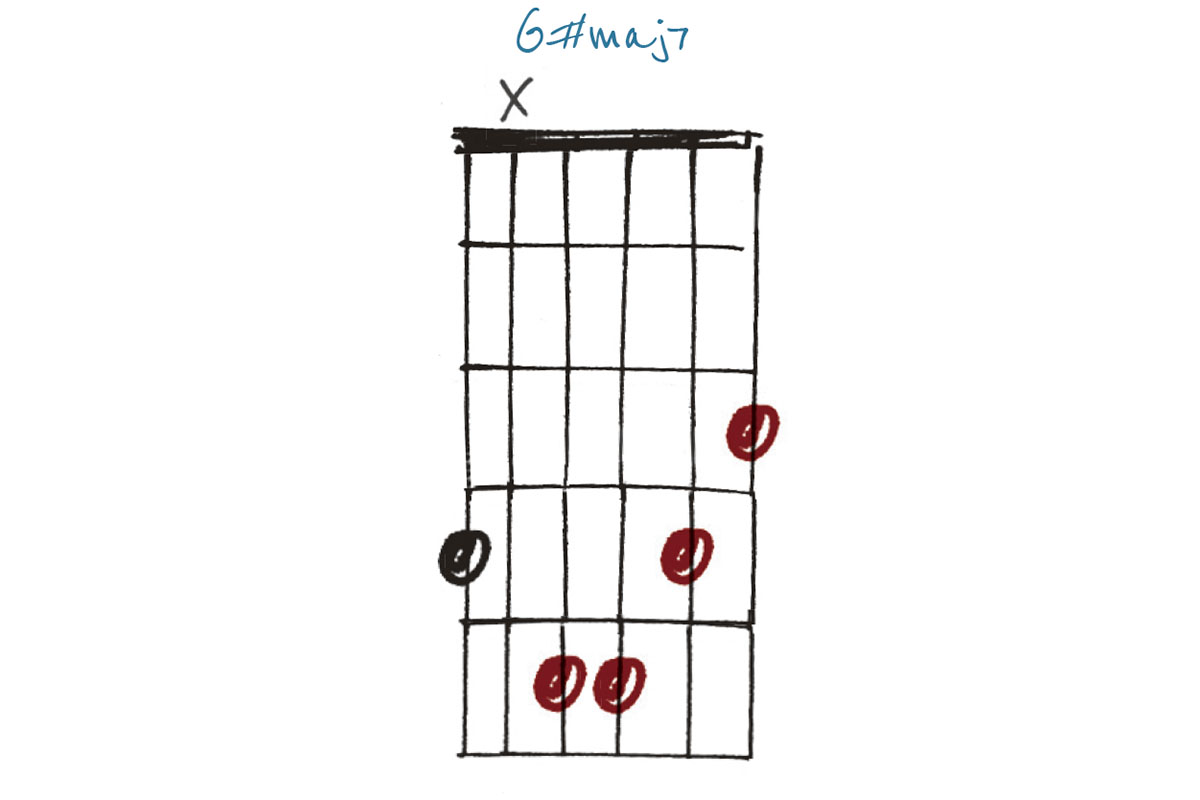

Example 24. G#maj7

This jazzy G# major 7 is an oddball with the muted fifth string and slanted barre to catch that F# (major 7th) on the first string. However, it’s worth persevering as this movable version of the major 7th is a nice alternative to add variety to your playing.

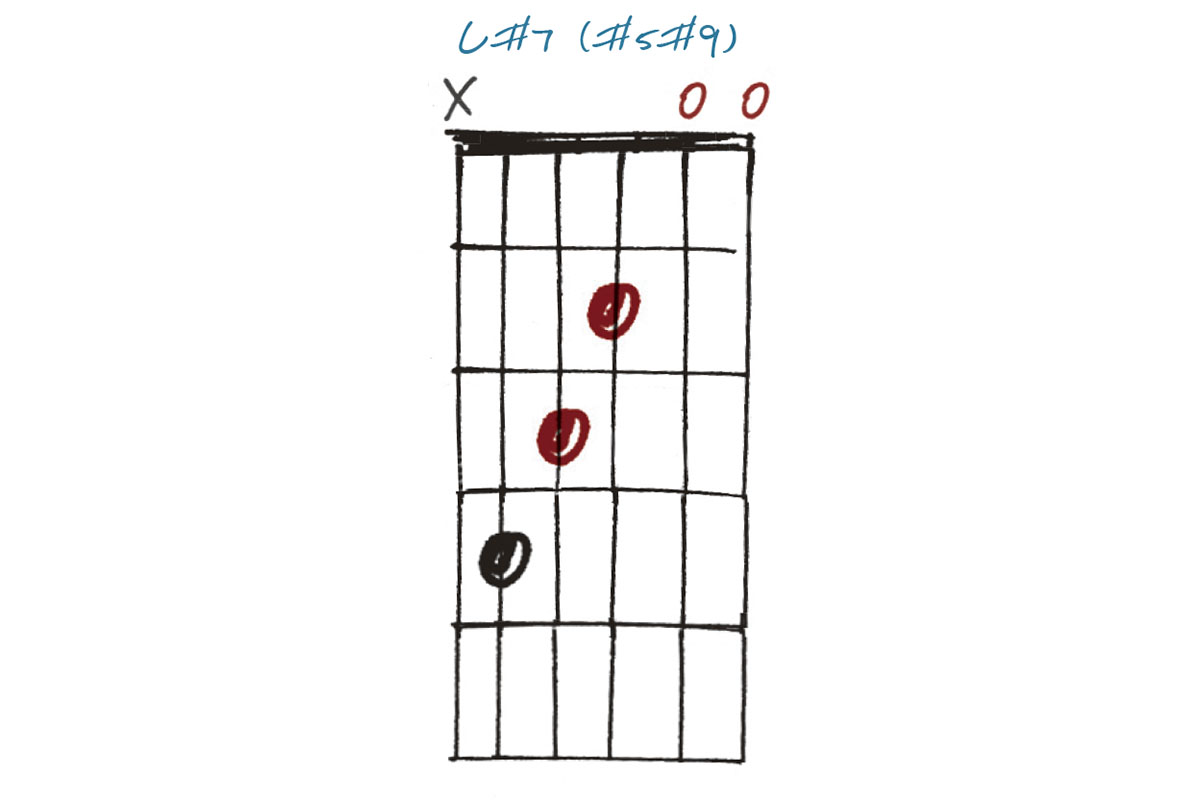

Example 25. C#7 (#5#9)

The first of our ‘bonus chords’, this C#7 (#5#9) is another great example of an easy to play chord with an intimidating name. Great for resolving to F# minor 11 (see Example 19), you’ll find the #5 (A) on the third string, with the #9 (E) on the open first string.

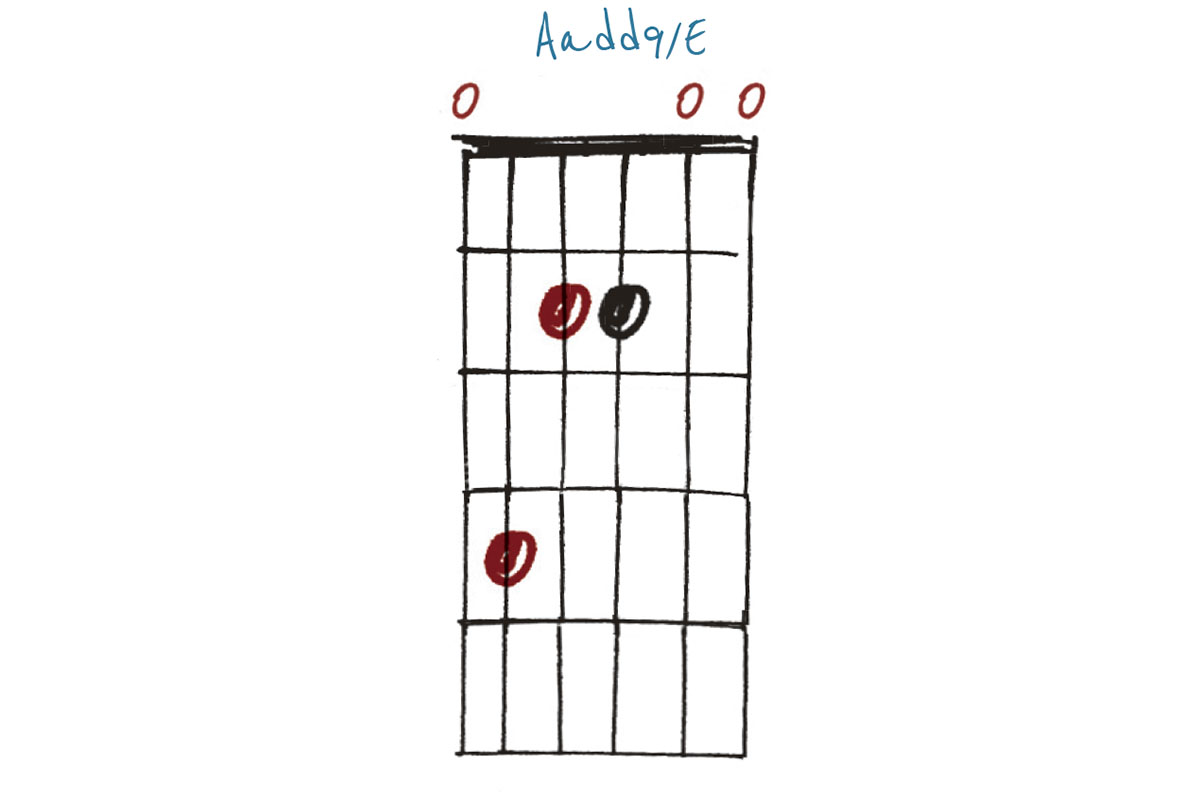

Example 26. Aadd9/E

This A add9/E sounds as though it could be in an open/altered tuning, but it’s easy to play and in a convenient open position. Try combining it with Examples 25 and 19 and you’ll be well on the way to creating a chord progression that keeps that strummed acoustic sound we all love – but with a twist!

Example 27. Em9

This voicing of E minor 9 is often used alongside or instead of E minor add9 (see Example 15), though be aware that adding that b7 (D) on the second string limits the movability of this chord – no harm in experimenting, though!

Example 28. Em11

E minor is one of the greatest chords on acoustic guitar, so no apologies here for yet another version! This E minor 11 features a barre at the second fret, giving us our 11th (A) on the third string and the 9th (F#) on the first string. By omitting the open sixth string, you can move this voicing to any key.

Example 29. F#m11(b9)

This dramatic F# minor 11 (b9) can be moved around to give everything from ‘bad guy walks into the bar’ to Jeff Buckley and more. We’re basically combining a powerchord on the lowest three strings with the remaining strings open and jangly. Great for strummed rhythms.

Example 30. Em/maj9

We finish with the ultimate ‘ending’ chord. This E minor/major 9 is not something you’ll hear on the acoustic every day, but perhaps that should be changed – starting from today!