“Two horrible things happened in the late ’90s: My father was kidnapped and I worked with the Weinsteins,” Guillermo del Toro once said. “I know which one was worse… the kidnapping made more sense, I knew what they wanted.”

Even 20 years after working with the Weinstein brothers, del Toro is showing scars from the experience. Of course, horror stories about the Weinsteins are everywhere. Del Toro spoke at the BFI London Film Festival just a week after The New York Times exposed Harvey as a serial sexual predator. However, he wasn’t talking about the disgraced movie mogul. It was younger brother Bob, and the age-old issue of studio interference, that made his life hell.

Del Toro’s relationship with the Weinsteins started promisingly. Impressed by the director’s 1993 debut Cronos, a bilingual indie horror about the resurfacing of an ancient mechanism that provides eternal life, the siblings asked him to contribute to a proposed three-part anthology dubbed “Light Years.” Del Toro was even allowed to pick the story, and after failing to land the rights to George R.R. Martin’s Sand Kings, the trio settled on adapting Donald A. Wollheim’s Mimic.

An early screenplay draft, co-written with Dragonslayer director Matthew Robbins, showed so much potential that Miramax said Mimic should be a standalone film (another installment in the series, Imposter, was given the same treatment in 2002, while poor Danny Boyle’s contribution, Alien Love Triangle, remains lost in the vaults). This is when the trouble began.

Producers began sticking their noses in before filming even started, insisting the villains of the piece should be cockroaches, not beetles. Del Toro was also forced to add expositional scenes which he believed robbed the monsters of their intrigue, and he faced constant demands to make their appearance more extraterrestrial.

Although del Toro has since established himself as a master of horror, Miramax repeatedly expressed concern that Mimic simply wasn’t frightening enough. At one point, an enraged Bob Weinstein reportedly marched onto the set and gave the future Oscar winner advice on how to make a movie. Only the intervention of leading lady Mira Sorvino, an actress whose own career would soon be sabotaged by a Weinstein, prevented del Toro from getting the boot.

Del Toro still had to compromise, although a director’s cut released in 2011 came much closer to his vision. The filmmaker managed to win a few battles, too.

Take the opening scene, in which the devastating effects of the fictional ailment carried by the roaches, Strickler’s disease, are laid bare in a hospital that looks otherworldly. Producers, hoping for a piece of routine Saturday night schlock, were apparently perturbed del Toro had dared to include any sense of artistic flair. And against Miramax’s wishes, the filmmaker also somehow managed to perform the unthinkable double whammy of knocking off two kids and a dog.

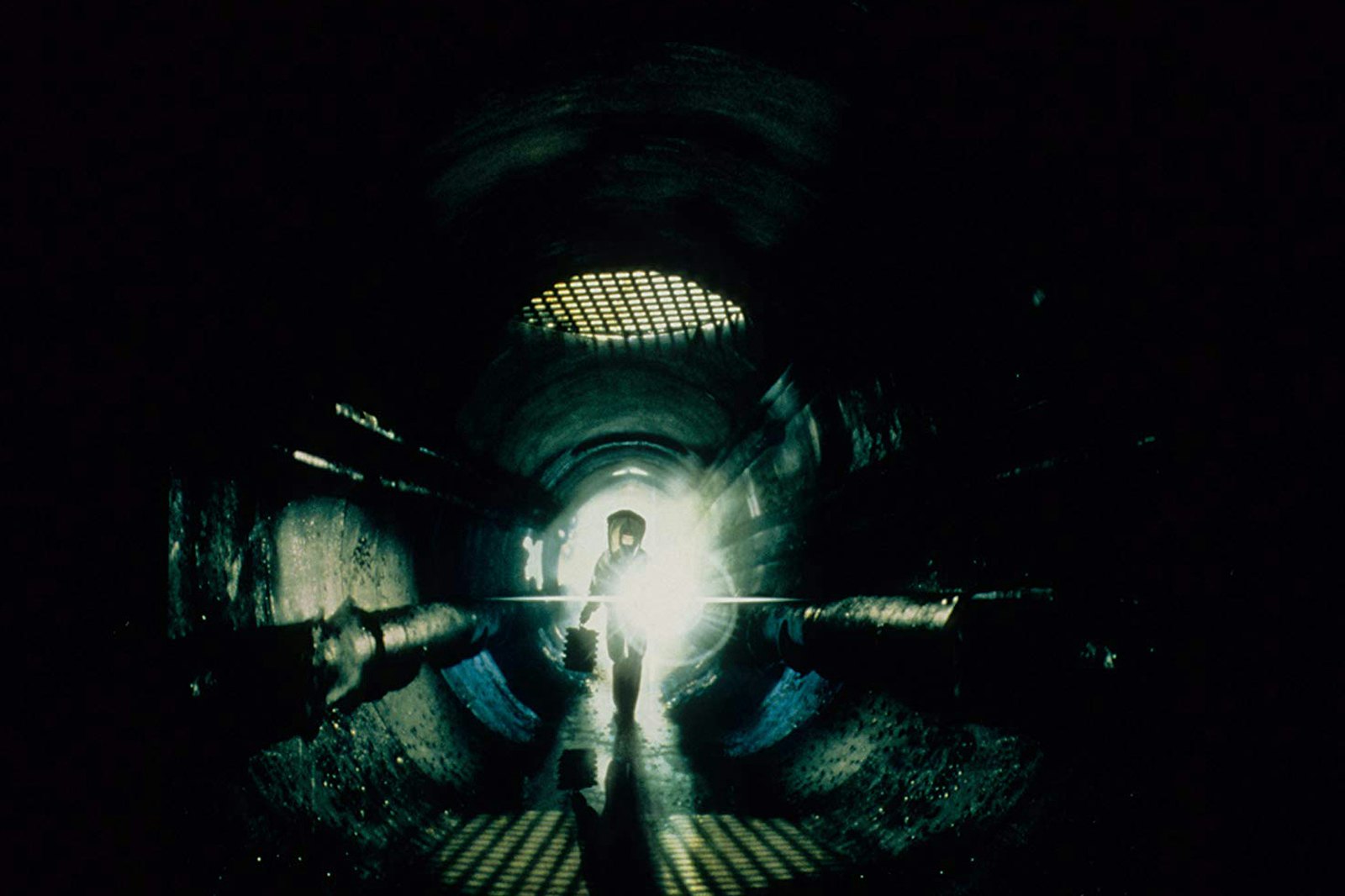

Considering the reservations about its fear factor, Mimic pulls few punches. Josh Brolin’s CDC assistant meets a grisly end at the hands of a Judas, the termite-mantis hybrid genetically engineered to starve the roaches plaguing New York City, but that end up causing far more carnage when they develop an uncanny ability to mimic mankind.

Del Toro’s festival admission isn’t the only time he’s spoken about his Weinstein ordeal. Just four years after Mimic’s release, he told IndieWire that although he developed friendships with Sorvino and Jeremy Northam, who played entomologist Susan Tyler and the CDC’s deputy director Peter Mann, shooting Mimic was unenjoyable. Then in a 2018 interview with The Independent, he said that, thanks to Bob’s meddling, he “never had a single day that was pleasant.”

Yet Mimic’s relentless on-set tensions did result in at least one positive: It helped del Toro form his signature visual style. With Weinstein’s shadow constantly looming over him, the filmmaker developed a more fluid approach to camerawork, ensuring his footage couldn’t be chopped to pieces. It’s why everything from Pan’s Labyrinth to The Shape of Water are such immersive fantasies. He even started hitting the editing suite daily to maintain more control. To this day, he still has a full-length cut of a film within a week of its wrapping.

And while the project deterred del Toro from venturing back into Hollywood for another five years — he’d return to Spanish indie cinema with 2001’s The Devil’s Backbone before taking the reins on Blade II — he still remains proud of its aesthetics. “I lost casting battles,” he said, “I lost story battles, but Mimic is visually 100% exactly what I wanted.”

His pride is well placed. Upon hearing what he’d unwittingly signed up for, del Toro remarked he’d been “condemned to doing the best giant cockroach movie ever made.” Alongside the cast’s committed performances, it’s the auteur’s inspired use of symbolism, color, and disturbing creatures that puts Mimic firmly in that squirm-inducing category.