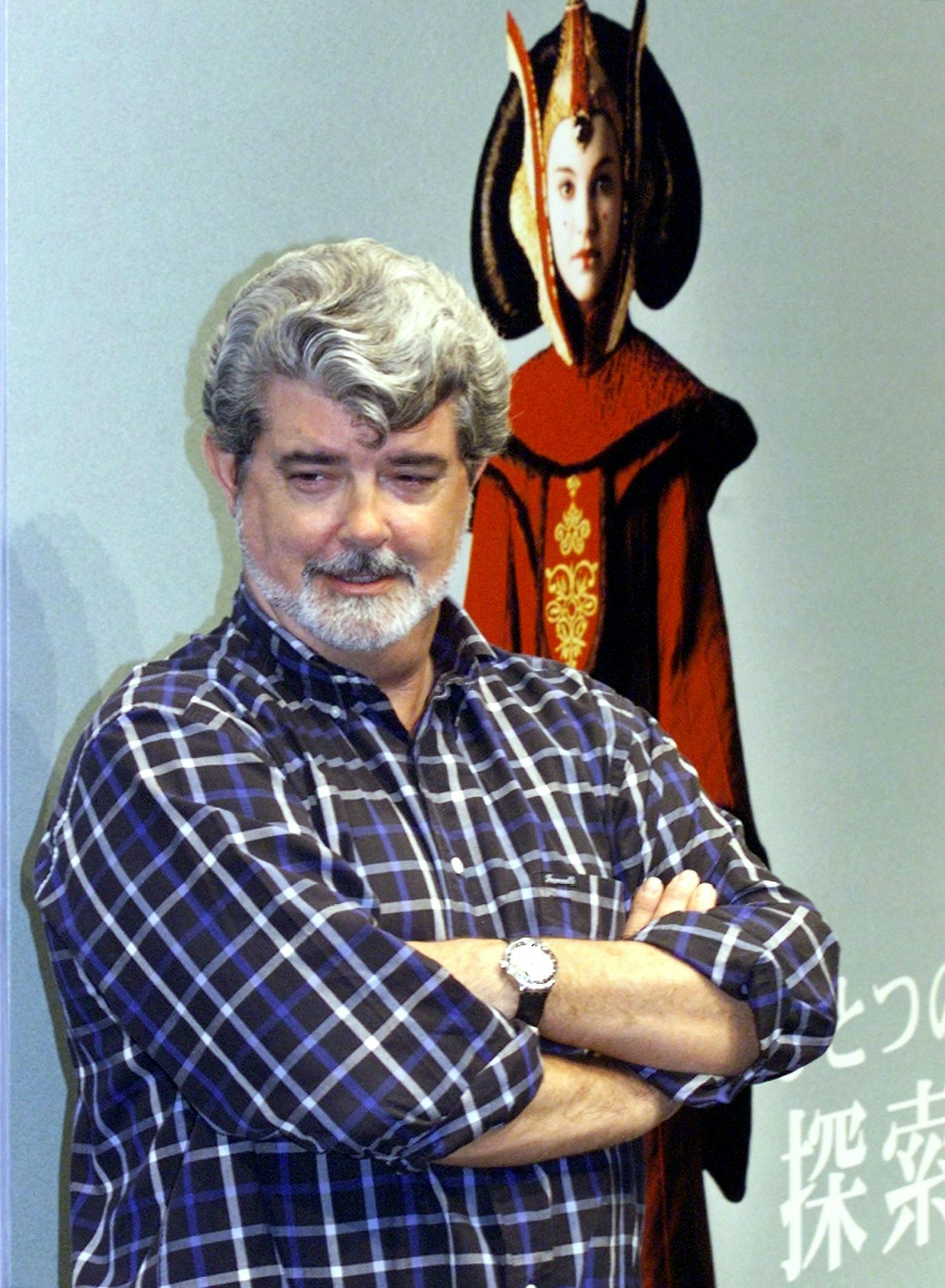

When George Lucas decided to turn his Star Wars backstory into a trilogy of new films, he had to, in his words, “develop an entire world.” That entire new world was Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace, a film that redefined Star Wars by making everything that was old and rundown look shiny and new. The Phantom Menace ditched the cobbled-together Millennium Falcon — a space truck with a supercharged engine — for the chrome-plated hotrod starships of the Naboo fleet. Obi-Wan Kenobi was no longer a bearded, wise old man in the desert; he was a clean-shaven baby-faced warrior played with precision by the indie movie darling of the time, Ewan McGregor.

A clean-shaven, very young McGregor — paired with Natalie Portman’s various ornate gowns as Queen Amidala — is probably the most perfect way to think about what the film did back then. In both 1999 and 2024, the best version of The Phantom Menace is the idea of The Phantom Menace, not the movie itself. This may or may not have been the intent, but as the most divisive Star Wars thing of all time turns a quarter century, the truth of how to love Episode I is to treat it like a brand-new toy that is best enjoyed if we leave it in the box.

Contrary to pervasive myths or fan assumptions, George Lucas did not have the specifics of Episode I laid out back in the 1970s when he crafted the first Star Wars — retroactively labeled “Episode IV” in 1981. In 1999, he admitted that “the story for the three new films was meant to be the backstory of the other films.” Right away, anyone who knows anything about writing at all should have a warning bell go off in their mind. If something was written merely as a backstory (a glorified outline), should that ever have been turned into its own story? Even Lucas admitted that this was not an ideal way to write a screenplay: “A lot of the story points were there. But the actual scenes and many characters were not.”

While many fans assumed Episode I would begin with Obi-Wan Kenobi and Anakin Skywalker kicking ass as Jedi in the good old days, we instead opened with a Jedi Master we’d never heard of: Qui-Gon Jinn, as played by the venerable Liam Neeson well before he became associated with the dad core action movies like Taken. This is the Neeson who had just played Jean Valjean in the 1998 Les Misérables and was nominated for an Oscar for the title role in Schindler’s List in 1994. Ostensibly, Qui-Gon Jinn is the main character of the movie, which is why, at the time, Hasbro released his green-bladed weapon as the first Episode I lightsaber toy.

As Qui-Gon, Neeson brings a chilled-out vibe to the heroics of The Phantom Menace that feels almost more at home with a Star Trek aesthetic than Star Wars. More Captain Picard than Han Solo, Qui-Gon embodies the peaceful zen strategies of the Jedi, which makes McGregor’s Obi-Wan the hothead, by default. This contrast barely works, mostly because Obi-Wan simply isn’t on screen as much as we’d like him to be. Interestingly, the one time Obi-Wan becomes a full-on aggressive, impulsive maniac it’s those emotions that allow him to defeat Sith warrior Darth Maul. For a moment, at the movie’s end, it’s almost like George Lucas forgot what his thesis was: Does allowing yourself to experience anger lead you to the Dark Side, or, in a more honest view, just make you more human?

Still, for all of Qui-Gon’s screentime, and seemingly important role as the character who gets the most done in the movie, our sympathies are supposed to lie with nine-year-old Anakin Skywalker (Jake Lloyd) and 14-year-old Padmé Amidala (Natalie Portman). Much has been said over the years about Lucas’ baffling choice to start the story here, when the most pivotal characters are so young. But upon revising the movie, it almost feels like Lucas is stalling for time. He’s not ready to make either Anakin or Padmé his main characters, so he lets Anakin basically slop into victory, and literally disguises Padmé throughout most of the movie, leaving us relatively clueless as to her true personality. When it comes to character work, The Phantom Menace is nearly all archetypes, with Lucas checking off his Jungian and Campbellian boxes, hoping the rest will follow.

In fairness, both in life and in fiction, George Lucas has never been known as a people person. As Mark Hamill once infamously said, “I have a sneaking suspicion that if there were a way to make movies without actors, George Lucas would do it.” In this way, The Phantom Menace is the most George Lucas-y of all the Star Wars products. He hired stellar actors for the majority of the roles, gave them the thinnest of characterizations, and hoped for the best. Qui-Gon Jinn, Jar Jar Binks, and Queen Amidala don't feel like people the way Han, Luke, and Leia did. They’re just elements of George Lucas’ world-building, which, at this point, regardless of what you think of the classic films, was nonexistent.

Despite how much fans and critics praise the minimalist world-building approach to the classic Star Wars trilogy, nothing really makes a lick of sense in those films. From the Empire’s finances to the way the Jedi work, we all made a lot of assumptions about those movies. In 1999, Lucas gave himself the impossible task of sorting it all out. “There was a tremendous amount of minutia in these movies that I had to consider,” Lucas said ominously, as if aware that in trying to make his galaxy far, far away more explicable, he was doomed to invite scrutiny he couldn’t have possibly wanted.

And yet, if we try to forget everything we know about Star Wars, or at least, try to lighten up on comparing The Phantom Menace to the original films, the reality is that twenty-five years later, it remains the most beautiful of the bunch. The podrace sequence is fantastic and engrossing; something that feels like a climax, and yet, is basically the middle of the movie. The lightsaber fights are kinetic. The score is perhaps the best John Williams has ever done for a Star Wars film, and when the emotional moments need to land — like the passing of Qui-Gon — everything works. There’s a more perfect version of The Phantom Menace embedded in the film we got. Sometimes when you see Doug Chiang’s lush conceptual art for the film, you glimpse that movie, a film even more reliant on its baroque palette than what was eventually released.

Separating the artistry of the Star Wars prequels from its primary artist, George Lucas, is nearly impossible. While unending analysis of the Star Wars phenomenon has generally ascribed the wild popularity to its universality, the paradox is that George Lucas has claimed that the movies, and the prequels in particular, were deeply personal. But when you watch The Phantom Menace today, what does that mean exactly?

Lucas didn’t want to tell the story of Darth Vader’s rise exactly the way we all expected. Instead, he wanted to recapture the same childhood zest for Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers he’d had when the notions of Star Wars first came to him. And so The Phantom Menace is his purest movie because it represents the one Star Wars movie where we can see clearly that he didn’t really compromise on anything. That would change in Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith were made: moments where public pressure, and the simple facts of his narrative, forced Lucas into certain corners. But with The Phantom Menace, Lucas was still content to play. And like all children at play, it’s not perfect, and very often makes zero sense — none of which makes it any less wonderful.