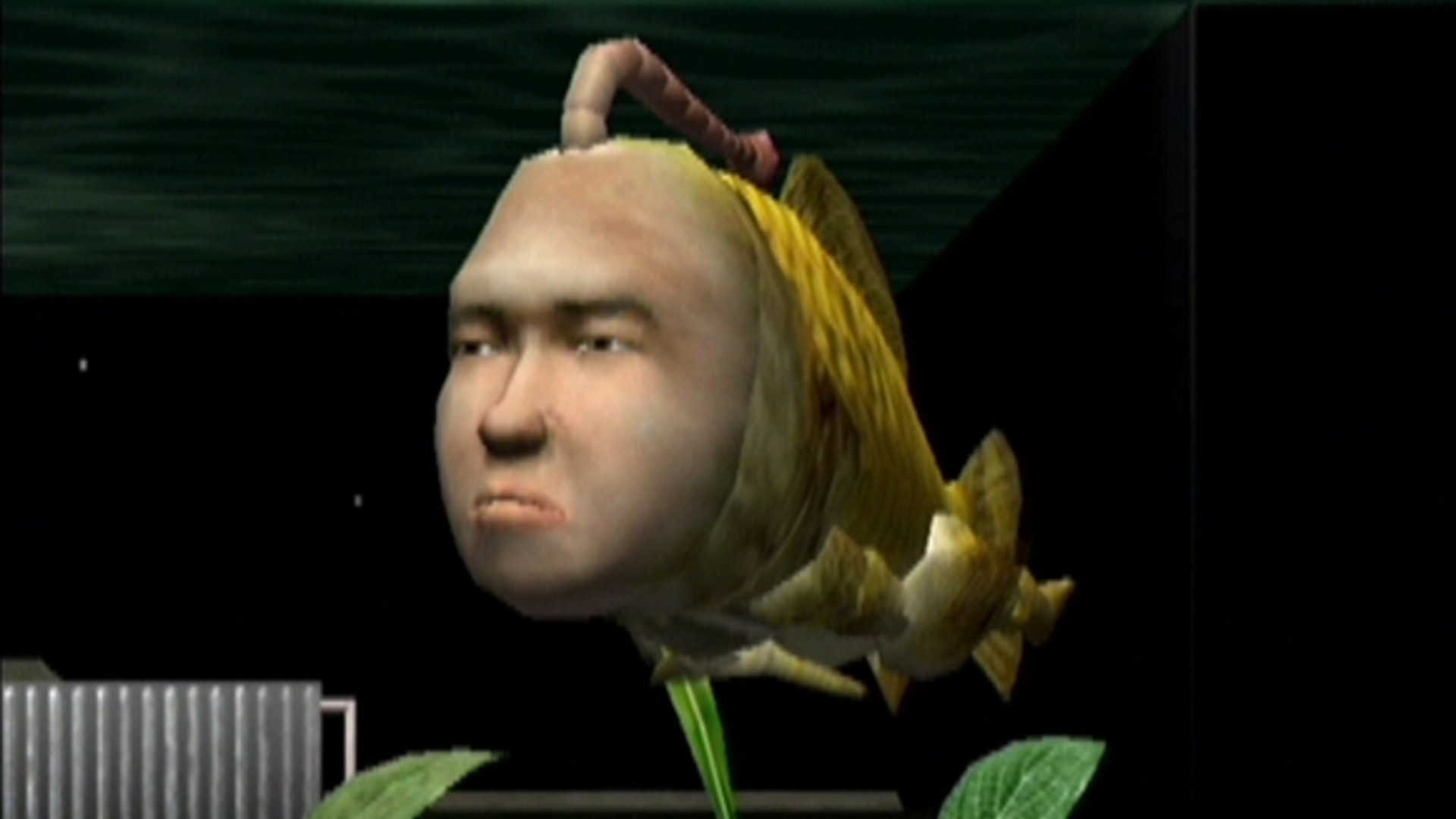

Out of the mouths of babes comes unexpected wisdom. In the case of Seaman, the babe is a fish with the face of an adult man. You've raised it diligently for weeks – hatching eggs, watching amoebae grow into gilled creatures that eat their brethren and then embark upon a secret, more complex third lifecycle – before it comes out with it. "Do you think the Internet is dangerous?" Seaman asks. You enter into a nuanced dialogue. It weighs up the advantages and disadvantages: the potential for conversation free of cultural prejudice or gender bias, the risk that without the need to leave our homes we might forget how to communicate face-to-face. It quizzes you about your views on Internet censorship. In the end, Seaman concludes: "It's up to you humans to figure out how to use the Internet intelligently, so that it won't harm you." Oh dear.

There are tech billionaires today that aren't operating on the same intellectual level. That Seaman would spawn into the world in 1999 is almost astonishing. Even at the time, it was a breath of fresh air. Part of a lineup designed to show off the capabilities of Sega's Dreamcast, Seaman was one of the first mainstream games to tie in-game occurrences to a real-time clock, and to employ voice-recognition technology via its bundled microphone peripheral. (Perhaps unsurprisingly for a game in which you could talk to this creature, it clinched the Gameplay Innovation win over Aliens Vs Predator and Silent Hill in 2000's Edge Awards.) It was ahead of its time. What's more shocking is that, a quarter of a century later, it still manages to feel contemporary.

Deep dive

Then again, creator Yoot Saito was preoccupied with making a game that was as broadly appealing as it was bizarre. Inspired by a silly lunchtime conversation at work, in which Saito and team discussed how they might add intrigue to one designer's tropical-fish simulator prototype, the Seaman project would evolve around "three opposites". First, Saito decided the game should be based not in fantasy but reality (for a given value of that term, at least). Second, your virtual pet would appear to live inside the television, demanding its needs be met daily – and looking directly out at, and addressing, the player. Saito wondered: what continually relevant and interesting activity loop might compel a human of any age, race or gender to boot up their Dreamcast multiple times a day? Easy. Talking about yourself, of course.

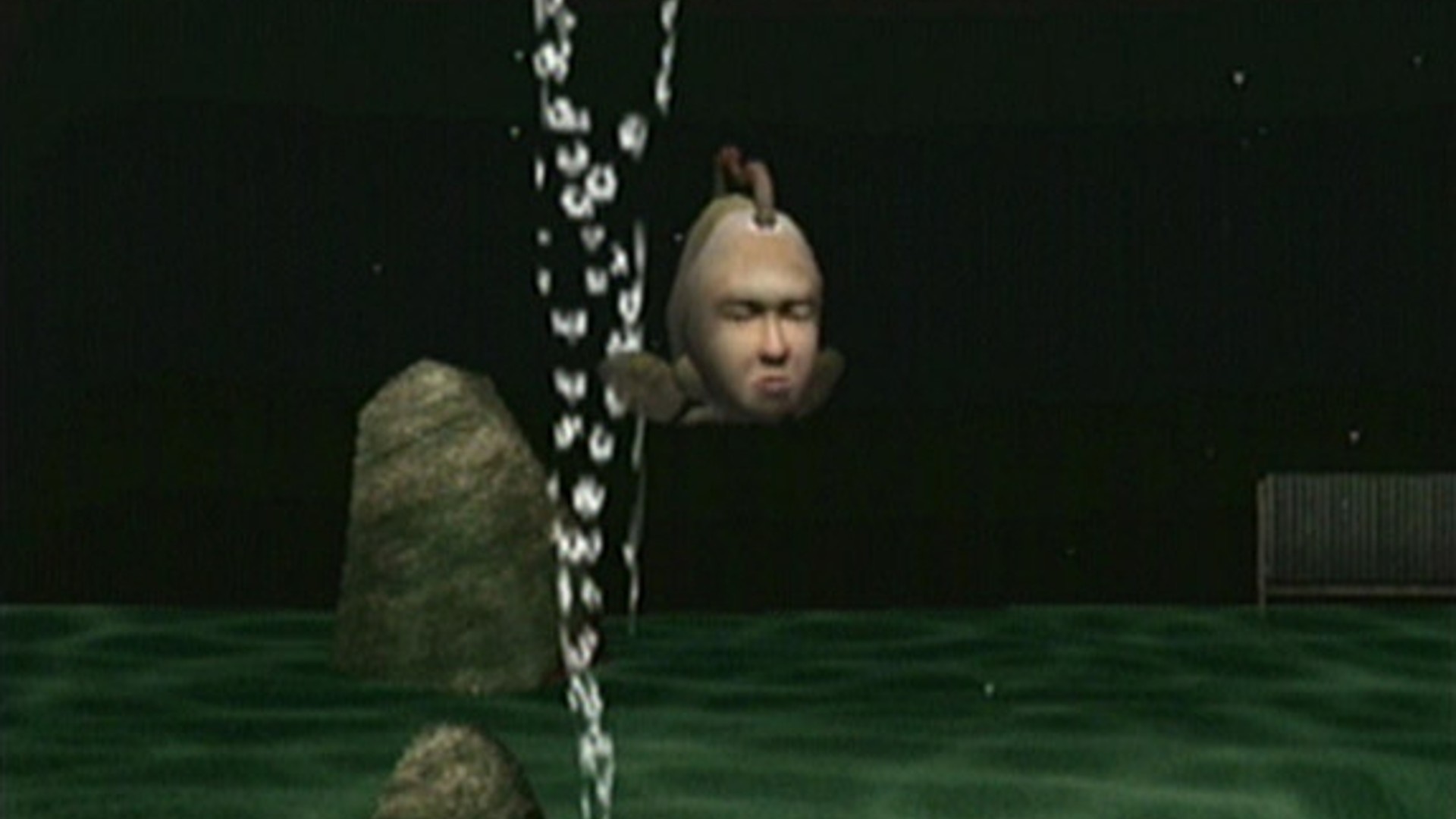

Initially, the game is simply about raising your Seaman: adjusting the tank's temperature, switching the lights on and off, misting a cage filled with larvae to cultivate its food. As it grows and starts to babble nonsense, you teach it language by talking into the microphone. Over time you encourage it to mimic simple words and phrases. But the real fun begins if you manage to keep it alive for multiple days or weeks. Then, Seaman will start asking you questions. How old are you? What's your star sign? What kind of films do you like? How's your relationship with your parents? Are you happy with your job? Do you like yourself?

Amazingly, Seaman appears to have a smart-mouth comment for every one of your answers, furnished with 20 hours of recorded dialogue, recognising a huge number of 'keywords' and remembering your prior responses. It's hilarious, both intentionally and otherwise. (Saito has an obvious gift for humour, but it's worth noting that the excellent US localisation of Seaman was handled by Jellyvision, better known nowadays as Jackbox Games.) If your Seaman struggles to understand keywords – not an uncommon occurrence – it insults you for not speaking clearly. "Why don't you go do something more intellectually stimulating," it sneers, "like eat paint chips?"

This feature originally appeared in Edge Magazine. For more fantastic in-depth interviews, features, reviews, and more delivered straight to your door or device, subscribe to Edge.

Elsewhere, in a conversation about our social circle, Seaman remarks that people sometimes aren't comfortable being by themselves because then they have to think: "I see you don't have that problem." Either it's pleasantly surprised we have friends, or it's telling us we have absolutely nothing going on upstairs. It's probably both – but we get off lightly compared to video game streamer Jerma985. When asked by Seaman, during a 2019 Twitch broadcast, what his biggest insecurity was, the streamer put himself on mute to provide a sheepish response – before Seaman repeated back to a live audience of thousands, "Your height?"

You'd better pray you're not having an affair, because Seaman will grill you on that too, somewhere in between enquiring about your mother's health and transmogrifying into a cannibal tadpole. This thing goes deep, responding with nonchalance if you tell it you're not heterosexual – as one Reddit user puts it, "Gay is the least of your worries. He'll find plenty of other things to judge you about" – and even putting forth a solid Cartesian argument as to why it exists, despite being a virtual entity.

Seaman's artificial intelligence isn't what we understand AI to be today. It's not a conversation engine: while the responses differ according to the time of day, tank conditions and player interactions, its 12,000 lines of dialogue are all prewritten scenarios. But it was well ahead of the curve, not least in its trawling for as much of your private information as possible. "Ha!" Seaman crows at one point. "My knowledge of your family grows ever more complete!"

Shifting tides

"In a 2019 GDC talk, Saito recounts telling his wife in 1997 about his idea for a game about a Sea Monkey with a human face. She initially responded with disgust."

Revisiting the game now, there are some dark laughs to be had at Seaman's prescient yet pantomime villain act, as it plays the robot after your data, your money – there are some great gags about selling you more Dreamcasts – and your job. Meanwhile, its creator has moved away from developing games to found the Seaman AI Research Lab, dedicated to developing a true Japanese conversation engine prototype. Having experienced hours of psychological duress at the hands of the talking fish he made two decades ago, we'll admit that the thought makes our palms a touch sweaty.

Considered purely as a game, however, Seaman's shadiness remains as refreshing as ever. Indeed, the last of Saito's "three opposites" rules for Seaman was that the creature be definitively not "cute". In a 2019 GDC talk, Saito recounts telling his wife in 1997 about his idea for a game about a Sea Monkey with a human face. She initially responded with disgust. But he was surprised when she checked in some time later on how his concept was going, insisting he develop it. He realised that "the opposite of hate was not like, but indifference". She hated the concept, sure – but she wasn't disinterested in it. It was a turning point for Saito: "The more you hate something, the more your mind becomes preoccupied by it." With the context of our present-day media consumption habits, it's another instance of uncanny foresight from Saito and his creation.

According to Saito, Seaman directly led to Dreamcast hardware sales to people new to videogames, and the majority of players were apparently women. Its marketing talked in terms of "raising" a Seaman, rather than playing the Seaman game, and ads were placed in women's magazines. The audience for the game certainly seemed more varied than many other games at the time, even if Seaman didn't exactly set the world alight, particularly outside of Japan. The collective shrug of the US in response to Dreamcast doubtless played a part there, and seeing the mainstream rise of more casual, tend-and-befriend games that accompanied Wii a handful of years later, we can't help but wonder whether Seaman might have had its moment in a different timeline. Wishful thinking, perhaps, for a game whose main character revels in "yo mama" wisecracks, and flings its faeces at you during tantrums.

In many ways, though, it is eerie how on the money Seaman remains today. It's ideal livestreaming fodder, from a time long before such a thing was a reality, and there's a subset of overenthusiastic people on TikTok nowadays who might call Seaman a "cosy game". Honestly? They're not totally wrong. In among all the infuriatingly precise animal husbandry, miscommunications and withering put downs, you will find there are plenty of touching conversations that leave you thinking about your fishy dependent long after the television is turned off. And then there is the game's ending – should you manage to get there.

At this point – whether it's through devoted daily play or time-skipping via the console's clock settings – you're rewarded with a rare moment in which Seaman's petulance and selfishness briefly falls away. It thanks you for taking care of it and conversing with it, its goodbye tailored around information you've shared over the course of your time together. And then, after a small meditation on freedom, it hops away in its frog form into the sunset. You might well find that you miss talking to Seaman as part of your routine. But there's a saying about loving things and letting them go, and this bittersweet ending captures how worthwhile it feels to have nurtured something into existence, even as it ultimately disappears into the wild. Even if what you've raised is a bit of a weirdo.

We wonder if the game's creator might have similar feelings. The difference between Saito and countless others joking about their strange ideas over lunch with friends is that he actually set out and made it. The result is a curiosity that struggled to succeed commercially. But it's one that, love or hate, no one could be indifferent to, with a timeless attitude and innovative spirit that lives on as a cult favourite. As Saito put it in 2019, to his audience of game developers: "Swim against the stream. Do not try to predict the future – just make it."

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more fantastic features, you can subscribe to Edge right here or pick up a single issue today.