When was the last time anybody knocked out an original sci-fi blockbuster franchise not derived from preexisting intellectual property? The closest qualifying contemporary examples are likely the Quiet Place series, John Krasinski’s alien invasion trilogy, and Avatar, for which the gap between the 2009 original and the 2022 sequel proved no obstacle for attaining massive box office success and critical plaudits

13 years is a long time. 20 years is even longer, 2004 being the year David Twohy ushered The Chronicles of Riddick, the sequel to his lean, mean Vin Diesel vehicle Pitch Black, released in 2000. The Chronicles of Riddick made big promises about things to come for Diesel’s roguish and rough-edged antihero. On account of a dismal box office take, that promise went unanswered. Yes, Twohy and Diesel released a sequel, Riddick, in 2013; no, that film’s back-to-basics pleasures weren’t a satisfying enough consolation prize for The Chronicles of Riddick’s cult following.

It turns out we live in a fair and just world, though, and while 12 years is a long time to wait, a fourth chapter in this series, Riddick: Furya, started production last August. (That’s 12 years at least; there’s no telling at present when the movie will be released.) Rejoice! Then tide yourself between now and Riddick: Furya’s future theatrical run with Arrow Video’s luxurious new 4K release of The Chronicles of Riddick.

For Twohy’s devotees, this disc is a treasure trove, featuring both the 119 minute theatrical cut and the 134 minute director’s cut. Riddick: Furya aside, it’s also a hangdog reminder of how damn close we came in the 2000s to getting a sci-fi franchise cut from whole cloth rather than stitched together from the threads of previously established work. Fortunately, the melancholy only lasts for as long as it takes for you to press “play” on the disc, replaced by the thrill of experiencing Twohy’s meathead Edgar Rice Burroughs riff anew. Pitch Black is a comparatively insular movie, revealing little about its setting, but The Chronicles of Riddick catapults that setting to a level of achievement that remains bafflingly unrecognized 20 years later. Twohy jams a whole universe into the film’s every frame, conjuring up an outlandish and goofy universe, but one he and his cast are so committed to that these details become features to celebrate, not deride.

And yet, derision is what met the film on release in 2004. Audiences rejected Diesel’s work as Riddick, along with Twohy’s vision, and the sight of Linus Roache self-disintegrating in immolating winds. They said “no” to Keith David, an actor whose presence elevates any movie he’s in. Most of all, they said “no” to something original, predating the industry’s late-2000s decision to go all-in on IP with a built-in viewership.

The Chronicles of Riddick is a hunk of Limburger that harkens to the era of Star Wars, Conan the Barbarian, and Heavy Metal. The film’s reference points are clear, and yet it is never referential. Diesel plays Riddick with such lived-in comfort that it’s easy to imagine him roleplaying the character in a home-grown D&D campaign, and that fundamental familiarity couches The Chronicles of Riddick’s narrative and plot within a context all its own. He likes playing Riddick. He seems to identify, on a primal level, with Riddick’s essence as an instinctual survivalist, while aligning with him on a human level through rugged empathy. Riddick puts up a convincing front of apathy. He’s wedded to the freedom afforded to him by his lack of personal attachments, and motivated by endurance. It’s these traits that instill in him a distaste for authority that propels him from “antihero” to just plain old “hero.”

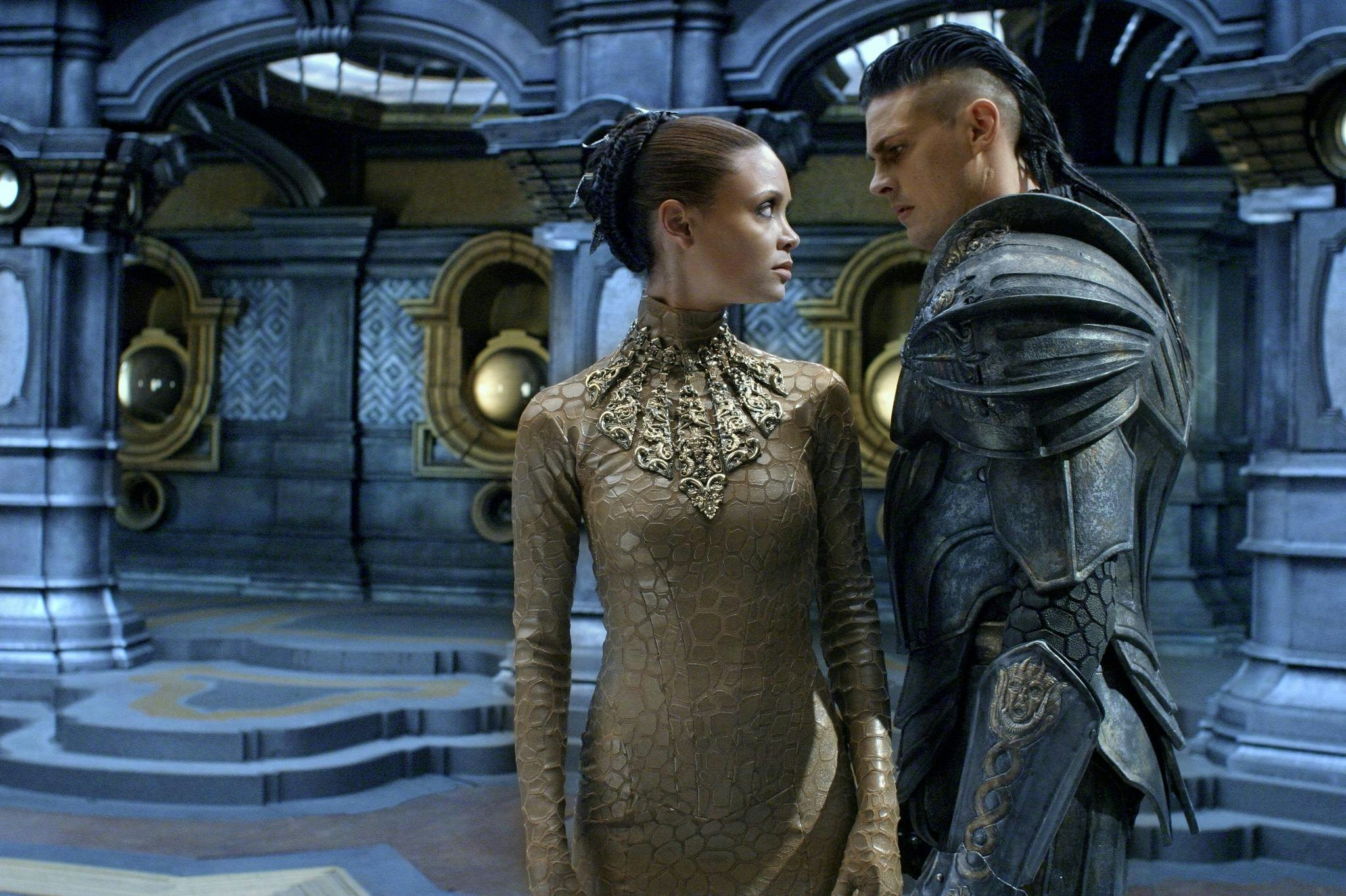

There’s a certain logic and intelligence to The Chronicles of Riddick that is belied by its stupider qualities. Twohy saves most of the former for Diesel, David, and Karl Urban (playing secondary villain, Vaako, with his trademark commanding burliness). The director dumps the film’s nitwitted material on Judi Dench and Thandiwe Newton, respectively playing the Air Elemental Aereon and Dame Vaako (the scheming Lady Macbeth to Vaako’s, well, Macbeth). They’re tasked with giving the film gravitas, and being serious, which isn’t the same thing as taking the material seriously.

Twohy makes the impossible happen, while also managing to tuck that impossibility within a creative vision equally otherworldly. He overwhelms his screenplay’s ill-advised particulars on the strength of its broader foundational ones. The Chronicles of Riddick is a messy movie, as imperfect an example of blockbusting genre cinema as anything produced within the American studio system in the last two decades. It’s a ride. Twohy takes the film to full throttle from the start. He shows no hesitation. He’s too confident that his hands will stay steady on the wheel, and rightly so, because they do. At its most dimwitted, the story maintains determined pace, pushing on to one epic set piece after another at awesome speed; at its best, characters make a mad rush across a volcanic planet’s surface in a desperate effort to outrun the sun.

In another film, this too would have been just one more dumb choice atop a pile of dumb choices. But in The Chronicles of Riddick, this moment, among countless others, triumphs over any intrinsic foolishness through sheer force of will.