Truly, there is nothing worse than a film that overstays its welcome – that horrible feeling of being in the cinema and checking your watch only to discover you’re less than halfway through. Even a great film will be hurt by an excessive runtime (Killers of the Flower Moon), let alone a bad one (ahem… Babylon).

That said, there are exceptions. In the right hands, a film can and should be allowed to sprawl for as long as is necessary. Take The Brutalist – the 215-minute epic starring Adrien Brody is as poignant as it is prolonged. Brady Corbet’s story of artistic struggle is so long that it comes with a 15-minute intermission, and yet it earns every second of its screen time.

In honour of The Brutalist, which has received 10 Oscar nods after cleaning up at the Golden Globes earlier this month, we’ve ranked 10 of the best movie epics across the ages. You may find there are some arguably glaring omissions – Ben-Hur, for example, is absent, as is Gone with the Wind – but these are the films we feel are worthy of your precious time.

(For the purpose of this list, a film must have a minimum duration of three hours in order to be eligible; sorry, Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, your two hours and 59 minutes doesn’t quite cut it).

11. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003) – 201 minutes

A common complaint of long movies is that they become boring. It’s thought that if a film is long enough, at some point or another there will come an inevitable lag. Refuting that argument with every second of its screen time, every blare of a warhorn and lash of a sword is The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.

Peter Jackson’s fantasy trilogy was miraculous in every sense of the word, an uber-epic that made fantasy lovers out of even the most staunch naysayers. Even more miraculous was that Jackson stuck the landing with The Return of the King, which sees Frodo (Elijah Wood) and Sam (Sean Astin) trek to Mordor to destroy the ring, with Andy Serkis’s Gollum in tow. Could it have been pruned in parts? Definitely – there seemed to be about four endings before the credits actually rolled – but there’s no denying the film’s entertainment value. Colossal in its scale and technically terrific, the film is a worthy finale to one of the century’s most influential franchises. Annabel Nugent

10. Happy Hour (2015) – 317 minutes

It’s wonderful to think that we live in a world where Ryûsuke Hamaguchi is an Oscar-nominated director. He received that accolade for his impeccable 2021 release Drive My Car. If you liked that film, dig deeper into his oeuvre and you’ll find Happy Hour, which clocks in at almost double the length of his three-hour-long Best Picture nominee. That said, it is anything but exhausting: Happy Hour is a refreshingly relaxed slice of slow cinema, focused on four thirtysomething women in a sleepy Japanese city. Your attention may wander – perhaps that’s part of the point – but Hamaguchi’s intimate depiction of friendship will hook you back in time and again. Jacob Stolworthy

9. Trenque Lauquen (2022) – 260 minutes

You might baulk at the idea of watching Trenque Lauquen – even more so when you learn it’s four hours long – but you’d be turning your back on a labyrinthine viewing experience that’s as close to hypnosis as one can get without a pendulum. This distinct Argentine-German drama from Laura Citarella comes in the guise of a straightforward mystery about the sudden disappearance of a botanist (Laura Parades), but slowly evolves into something else entirely: an epic tale split into 12 sections, with shades of Hitchcock and Lynch – while remaining totally unique in its own right. JS

8. An Elephant Sitting Still (2018) – 234 minutes

A pall of sadness hangs over the Chinese film An Elephant Sitting Still, whose director Hu Bo died by suicide aged 29 after completing it. The movie he left behind is an elegiac hymn to hopelessness, its bleakness only exacerbated by its mammoth running time. While you may not be sitting as still as the elephant of its title, four hours devoid of cheer is admittedly a daunting endeavour, but should you feel up to it, you’ll discover a filmmaking masterclass unlike anything you’ve seen. Hu Bo’s sensibility washes over you, leaving a lasting imprint – even if you might never want to watch it again. JS

7. The Irishman (2019) – 209 minutes

Sad, funny, and very violent, The Irishman is Scorsese through and through. The film tells the story of Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro), a Second World War veteran turned Mafia hitman turned union leader, pulling focus on his friendship with Teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino). Gingerly paced, The Irishman deftly shifts between eras using flashbacks within flashbacks and de-aging technology, which manages to feel remarkably un-gimmicky here. Scorsese vets – De Niro, Harvey Keitel, and Joe Pesci – are reunited and on top form, with Pesci especially turning in a superb performance as a man of quiet restraint.

The Irishman has its detractors, as any film over three hours always does, but it earns its screen time in spades. Scorsese is often seen as a fast and furious kind of filmmaker, but in slowing things down, he allows each scene, masterfully directed and acted, to bloom more fully – like algae in water, unfurling in microscopic, careful detail. AN

6. The Right Stuff (1983) – 192 minutes

There’s a scene in The Right Stuff in which test pilot Chuck Yeager, having returned safely to earth after breaking the sound barrier for the first time ever, walks away from his wrecked sonic jet, his face burnt black and helmet heavy in his hand. Chills! Philip Kaufman’s 1983 space-race flick certainly does the Mercury Seven justice, giving the epic true story of America’s first astronauts an appropriately ambitious retelling.

It’s strange to think the film flopped at the box office, but that didn’t stop it winning four Oscars – and in the years since, it has been exalted to the heights it always deserved. Sam Shepard is pitch-perfect as Yeager, who slots seamlessly into the pantheon of Great American Heroes, cowboy hat and stiff upper lip included, while Ed Harris, Scott Glenn and Dennis Quaid round out a stellar ensemble cast. That so much of The Right Stuff stays true to the real story is a bonus – certainly, it’s among cinema’s most entertaining history lessons. AN

5. Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) – 202 minutes

In 2022, when Jeanne Dielman beat Vertigo and Citizen Kane to the top spot in Sight and Sound’s greatest film of all time poll, more casual film watchers were galvanised to experience Belgian director Chantal Akerman’s masterpiece for the first time. On the surface, Jeanne Dielman is a slice-of-life drama depicting the day-to-day routine of a widowed housewife (Delphine Seyrig). But it’s also a fascinating exploration of the experimental, with the repetition of Dielman’s actions (making her bed, washing up, peeling potatoes) taking on a spellbinding form – altering the parameters of your own patience. Some will call it avant-garde, others will brand it boring. But regardless of your stance, Akerman’s film is an essential experience. JS

4. Fanny and Alexander (1982) – 188 or 312 minutes

It’s a small mercy that Ingmar Bergman’s longest ever film is also one of his warmest, with sumptuous scenes of family Christmases and magic lantern shows. That said, Fanny and Alexander is still a Bergman film and so contains all the angst, grief and strife we’ve come to expect from the late, great Swedish director. The film, a deeply personal endeavour for Bergman, takes place in Uppsala in the 1900s and follows siblings Fanny and Alexander, whose upper-middle-class upbringing is rocked when their father’s death brings the fraught arrival of their new stepdad, a bishop played by Jan Malmsjö. The film also boasts an ensemble cast second to none, a roster of indelible characters whose names could serve the title as well as Fanny and Alexander.

For all its bawdiness and comic relief (in Sweden, it is considered to be a Christmas film), the movie is a psychological drama that delves deeply and darkly into themes of abuse and questions of religion. It’s a satisfying, hearty meal of a movie – and for dessert, why not try the unabridged five-hour version? Somehow, it’s even better than the three-hour one. AN

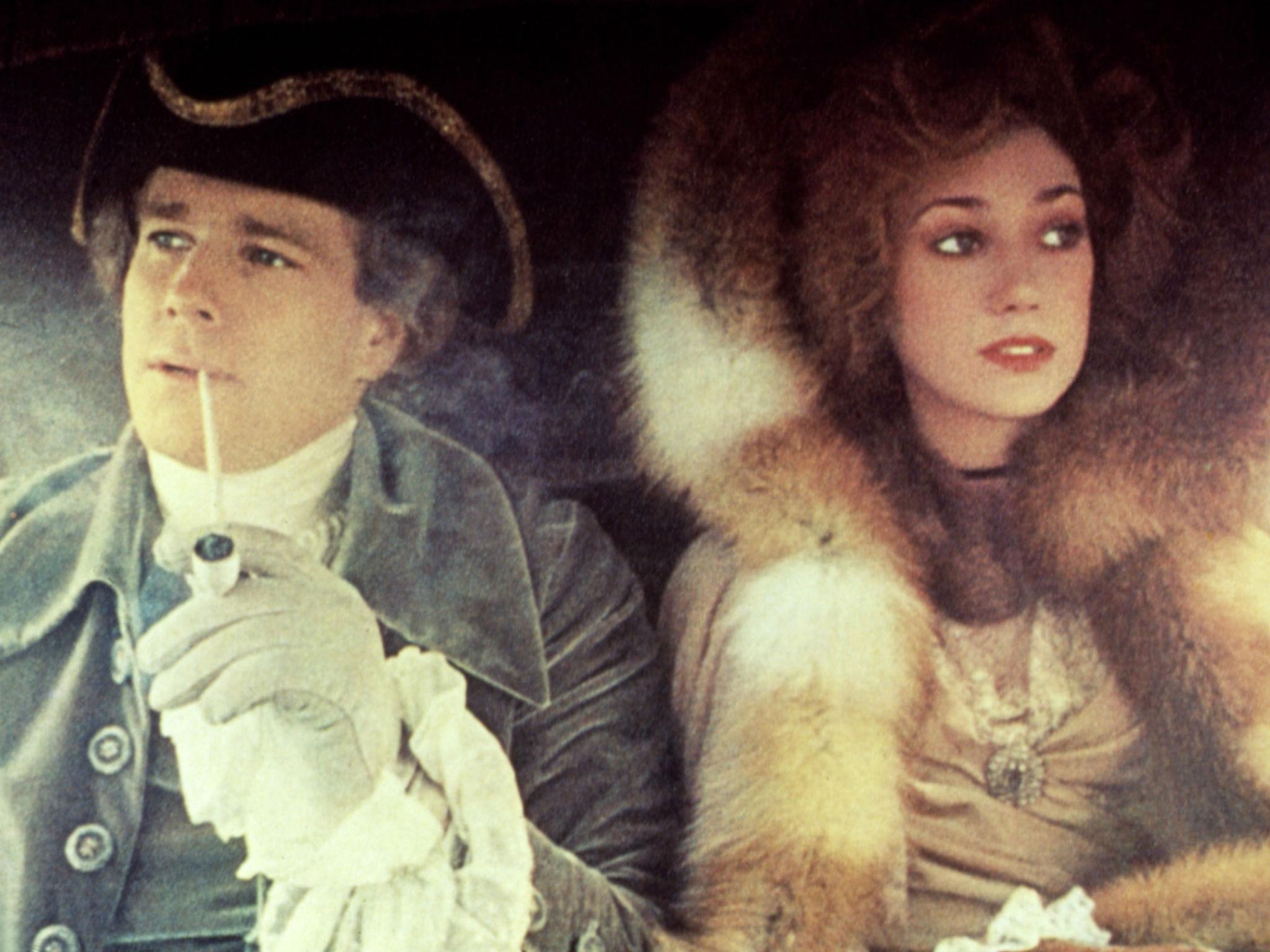

3. Barry Lyndon (1975) – 185 minutes

When people name their favourite Stanley Kubrick films, the populist choice might be The Shining or my personal pick 2001: A Space Odyssey, but Barry Lyndon has increasingly found favour over the years among those cooler individuals whose, say, favourite Beatle is George Harrison. It’s certainly a superior work. Barry Lyndon stars Ryan O’Neal as an 18th-century gold digger whose marriage to a rich widow has everything to do with his desire to climb the social ladder. It’s wonderfully restrained filmmaking from Kubrick, bolstered by the three-hour runtime, bitingly funny and lavish as hell. JS

2. Seven Samurai (1954) – 207 minutes

No list about epic films is complete without a mention of Seven Samurai. Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 period film (or jidaigeki) tells the story of 16th-century villagers who reluctantly enlist the help of mercenaries (can you guess how many?) to protect them from invading bandits. The film is as epic as its story sounds: rain-drenched battle sequences so thrilling they put today’s CGI scenes to shame. As entertaining and brilliantly executed as those scenes are, however, there’s plenty more going on besides the glint of swords. The film deals with questions of duty and social responsibilities, society and standings with an expert hand – unfolding a clear narrative that drives the story much faster than its 207-minute runtime might suggest.

It’s hard to overstate the influence that Seven Samurai has had on cinema; it’s often said that Kurosawa was the first to conceive of a concept in which a team is assembled to carry out a mission – a staple on screen today. Most famously, John Sturges remade the film into The Magnificent Seven in 1960, and later it inspired George Lucas to make Star Wars. Still, Seven Samurai remains singular in its pioneering vision. AN

1. Les Enfants du Paradis (1945) – 190 minutes

Settling down to watch Les Enfants du Paradis on your couch at home, you’d be forgiven for forgetting you’re in your living room and not in a theatre. Curtains are wont to appear on screen in Marcel Carné’s wondrous spectacle, separating the viewer from the magic before they open and – bam! – you’re transported to Paris circa 1830. That Carné made the film under fraught conditions towards the end of the Second World War only adds to its magnificence. The US trailer for Les Enfants du Paradis branded it “the French answer to Gone with the Wind”, the much-loved romance epic starring Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable. Scrap that; it’s even better. JS