The August sun pulsates overhead as my family and I arrive at the doors of our hotel in downtown Victoria. It’s just shy of 7 p.m., the tail end of a long day that included planes, ferries, and a three-hour time difference. For my wife, Elizabeth, our two young kids, Maddy and Max, and their mah mah and yeh yeh (paternal grandmother and grandfather respectively, in Cantonese), this is our first trip outside Ontario since the pandemic. The kids are hungry and exhausted. We need food. Quick.

My family starts unpacking while dad and I hop back into the car to procure some takeout. Chinatown is close by, and I’m keen to check out a modish joint offering an upmarket take on Asian street food. To my dismay, there’s a line, of seven or eight people, curling outside the restaurant. I pull out my phone, ready to deploy Google Maps to throw up another option. But like at so many other times in my life, my father has the answer: Don Mee.

To many people in Victoria, Don Mee is an institution. It opened for dining in 1940, but its roots in the community stretch back much further. A gentleman named Lee Gan started the Don Mee animal feed store on Government Street in 1922, the year before the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. Two years later, he opened a butcher shop at 538 Fisgard Street. Eventually, he expanded the store to include a dining room on the floor above. By the 1960s, Lee Gan had stopped running the feed and butcher shops, but Don Mee the restaurant remained. For people like my dad, Andrew Chiu-Kun Ma, this place was a haven.

He came to Victoria from Hong Kong in 1973 as a seventeen-year-old. Back then, it was common for Chinese families—at least the ones who could afford it—to send their kids to schools overseas, believing a Western education would open up more opportunities. My dad, following in the footsteps of his elder brother, George, enrolled at St. Michaels University School, a prestigious boarding school with military heritage. He was one of a handful of non-white students and wasn’t immune to racist jibes. The first six months were the hardest, he recalled, pining for his family and the only life he had ever known. He would later tell me his father made a smart decision by limiting his weekly allowance to $2 even though his family could afford more.

“Because two bucks a week was enough for pocket money at the time but not enough to save up for a plane ticket,” he said.

The money would often go toward a meal from Don Mee. He and the other Chinese boys would pool their spare change and order delivery to their dormitory when they could. On rare occasions, they would take the bus into Chinatown and eat inside the restaurant, happy to hear their native language.

When we arrive, the place is a third full, the average age of the diners around sixty. My dad starts a conversation in Cantonese with an affable, middle-aged server named Gary as I study the paper takeout menu. The menu reflects Don Mee’s origins as a restaurant striking a balance between classic Cantonese dishes—like pork hock with shredded jellyfish or, a personal favourite of mine, crab and fish maw soup—and fare more amenable to Western palates—like egg foo yong or crispy fried ginger beef (which Alberta can lay claim to creating in the 1970s).

My father asks if they have herbal chicken feet soup. Upon learning that it hasn’t been on the menu for years, he tells the server he used to eat it at the restaurant fifty years ago.

This delights Gary, and they swap stories about living in Victoria. When our food is ready, we promise to return later in the week with the rest of the family.

Back at the hotel, the kids tear into sweet and sour pork, dumplings, and chicken fried rice. The food itself is nothing special. But sitting there, surrounded by my kids, my wife, my parents, and an ocean-cooled breeze blowing through the open windows, I know I am having one of the most perfect meals of my life.

We could have gone anywhere for our first family holiday after the worst of COVID-19 had passed. But three generations of my family have travelled to British Columbia for a reason. We’re here because I’m searching for something I felt I had lost a bit of during the pandemic: my sense of belonging, my connection to this country, my very identity as a Canadian. We’re in Victoria, where my father first arrived in the country, to show my children exactly where our family’s Canadian story began.

I was born in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1983 and grew up nearby in the predominantly white, leafy suburb of Ancaster. Like my father, my mother is also originally from Hong Kong. I was one of the few—sometimes only—students in class from a visible minority group. Much of the time, I didn’t get the impression that my life was very different from the lives of any of my friends, who were all white. We listened to the same music, played the same video games, and saw the same movies. But I clearly recall many moments that entrenched within me a sense of otherness: a jerk in a parking lot shouting racial abuses at my parents over who got to the spot first, kids at school making fun of their accents, jokes that I shouldn’t be let near someone’s dog because “you people” eat them. In my hometown, I was the Chinese kid who couldn’t play during the day in the summer because his parents made him go to Cantonese school and who brought “weird shit” for lunch in his Thermos. (For the record: it was usually my mom’s soy sauce and ginger chicken, which was legitimately wonderful.) I didn’t want to eat Chinese food all the time; I wanted stuffed-crust pizza. I didn’t want to learn to speak Chinese; I wanted to play the guitar and start an angsty rock band. As I got older, I felt like I had to pick a lane. I stopped referring to myself as Chinese Canadian for a while. Couldn’t I just be Canadian?

When I was twenty-one, I gained a different perspective after visiting Hong Kong to help my yeh yeh make the fifteen-hour flight to Toronto. My childhood best friend, Matt, tagged along on this occasion, and travelling with him made me see Hong Kong from an entirely different perspective. We ate, drank, and explored our way up and down the city, from the bustling district of Wan Chai to the street markets of Kowloon and the walled villages of the New Territories. I came home with a renewed admiration for my heritage. I also came away with a sense of regret that I had ever felt embarrassed about being Chinese.

I began writing stories and interviewing other Chinese Canadians about their experiences and came to see how truly broad and diverse the Chinese diaspora was. While the majority of Chinese Canadians trace their origins to mainland China and Hong Kong, many have familial roots in Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, and also the Caribbean, Africa, and beyond.

But, more significantly, I was confronted with my embarrassing lack of knowledge of the previous generations of Chinese who had contributed so much to this country. The history of the Chinese in Canada had been relegated to minor appearances in the textbooks I had read growing up.

The British Columbia gold rush in the mid-1800s saw some of the earliest Chinese arrive in Canada to seek their fortunes in Gum San, or “Gold Mountain.” A couple of decades later, the Canadian Pacific Railway would bring in thousands of workers from China to build our national railway, paying these men roughly half as much as the white workers despite being tasked with the most dangerous jobs and toiling under severe work conditions. One of the deadly tasks was to handle nitroglycerin, used as an explosive to break rocks. It was a highly unstable substance, and fatal accidents were common enough for the phrase “a Chinaman’s chance in hell” to be coined in Californian mines. Once work on the railroad was completed, the federal government started levying a “head tax” on the Chinese entering Canada, in an effort to discourage them from coming. Starting at $50 in 1885, the amount rose to $100 in 1901, after it had little impact on keeping the Chinese out. It was then raised again in 1903, to $500, the equivalent of two years’ wages for most labourers. People worked for years to pay off the debts they incurred by borrowing money to pay the tax. But the horrific famines, droughts, and political unrest in China led more than 97,000 Chinese immigrants to come to Canada between 1885 and 1923 despite the punishing entry fees. In addition to the head taxes, Chinese Canadians were also excessively documented and forced to register to be tracked by the government, their Chinese immigration, or “CI,” cards forever a reminder of their tenuous status in this country.

The Chinese, like many other racialized communities, had been frequent scapegoats for the country’s economic woes. But pressure from trade unions, veterans’ associations, and politicians leveraging the general population’s fear and hostility toward the Chinese had reached a fever pitch, and the calls to end the “Yellow Peril” had become deafening, by the 1920s.

In 1923, the governing Liberal Party of Canada, led by prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, revoked the head tax and replaced it with the Chinese Immigration Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act. The heavy-handed exclusion act virtually stopped the immigration of people of Chinese descent: fewer than fifty Chinese newcomers would be let into the country in the twenty-four years the act stood. It’s believed to be the only time in Canadian history that an entire race of people has been barred from immigrating here. The law devastated the Chinese Canadian community, tearing families apart, sometimes forever. That the law was passed on July 1, then known as Dominion Day but now as Canada Day, added a further dimension of cruelty to the deed, particularly for those who had died building our railroad or spent their life savings paying the head tax. Indeed, to those in the Chinese Canadian community, the day would be known as “Humiliation Day.” It was only after the atrocities of World War II forced countries around the world to reevaluate their human rights policies that the exclusion act was repealed, in 1947. But it would leave a permanent scar on generations of Chinese Canadians.

I found inspiration in the stories of people like Wee Hong Louie, born near Shuswap, BC. He and his brother had both enlisted to fight in World War I despite not being recognized as Canadian citizens. Wee Hong returned home, having earned the British War Medal and the Victory Medal. When he was turned down for a licence to start a radio shop, he sent his army uniform and medals to Mackenzie King himself, wondering how someone who had fought for Canada could be treated this way. He received a letter of apology from the prime minister, his medals back, and his licence. There were other stories about the resilience of the Chinese Canadian community—of the numerous men and women who had served our country during World War II despite not being able to vote. For much of early Canadian history, our political institutions had sought to exclude visible minorities, women, and Indigenous communities from voting. It was only in 1948 that the right to vote was extended to Canadians of Asian origin.

Activists like Foon Hay Lum, who was separated from her husband for decades because of the exclusion act, later helped establish the Chinese Canadian National Council and fought for redress for the head tax and immigration ban. She was personally on hand to watch prime minister Stephen Harper deliver an official apology in the House of Commons on June 22, 2006.

Learning about the generations that came before me made me rethink my relationship to this country in a deeper, more meaningful way. I was a beneficiary of their struggle, their advocacy, and their sacrifices. To them, citizenship was hard won. I vowed I wouldn’t take mine for granted.

When Wuhan went into lockdown because of a mysterious respiratory virus in early 2020, I remember the prevailing sentiment among our friends and family members was one of surprise. We figured this was something of an overreaction on China’s part. I was used to seeing people wear face masks on public transit in Hong Kong, Japan, and other parts of East Asia and chalked it up to a culture of caution.

But then I started seeing “Wuhan virus” plastered all over the headlines and increasingly hostile rhetoric about the “Chinese virus” and its origins blowing up on social media. It reminded me of the SARS outbreak of 2003, when I was a first-year university student. Back then, I had heard about Chinatown stores being vandalized and some idiots harassing elderly Chinese folk in the streets. On campus, I felt physically safe, but the increase in racist comments—mostly in the form of jokes or people jumping three feet away for comic effect whenever one of us Asian students coughed or sneezed—didn’t escape me.

But COVID? COVID was different.

The tenor of the racism this time was far deeper, more intense. Social media ratcheted everything up, normalizing hate speech and gassing up white replacement theory, which had been considered a fringe movement but has been gaining traction across North America for decades. There were reports of attacks, slashings, and stabbings. Incidents of anti-Asian violence and harassment spiked significantly during the pandemic, according to the Canadian Human Rights Commission: 43 percent of Canadians with Asian heritage reported having been threatened or intimidated as a direct result of COVID-19. On March 16, 2021, a man in Atlanta shot and killed eight women of Asian descent working in spas, highlighting the fact that women were far more targeted in such cases of violence. In Canada, 60 percent of the accounts of anti-Asian harassment incidents came from women, according to a 2020 report.

For the first time in my life here, my body would tighten with fear whenever I got on the subway or walked on the streets. I thought I had come to terms with my identity as a Canadian, feeling proud of my heritage and believing that I belonged in this country, a privilege previous generations of Chinese Canadians had striven for me to have. But now it felt like the “Yellow Peril” era again. Scrolling through Twitter responses to news stories, I saw Asians were once more being branded as dirty, uncivilized, a threat to Western society. Then, in early 2022, the so-called “freedom convoy” descended upon Ottawa, imbuing the Canadian flag—the very same flag I had looked at when I stood up and sang the national anthem every morning as a kid—with a more sinister symbolism.

By May that year, it felt like much (though not all) of that vitriol had waned, as had the darkest hours of the pandemic. But another incident made me feel like a stranger in the only country I’ve ever lived in. On a trip to visit my parents, my mother and I took my six-year-old daughter, Maddy, for her first ever proper haircut. The hair stylist remarked on my mother’s youthful appearance and admired my daughter’s long chestnut tresses.

“But where are you guys from?”

The question caught me off guard. My mother replied that she was from Hong Kong. “These kids were born here.”

Brushing Maddy’s hair with a comb, the stylist said, “Oh right. . . . I didn’t think she looked Canadian.”

I didn’t know what to say or how to react, just felt that familiar tightening in my body. Her words reverberated in my head: “I didn’t think she looked Canadian.” I know her intention wasn’t to offend and was born of genuine curiosity. She was a person of colour herself, and this was likely telling of her own personal experiences.

My daughter is Canadian, though. My wife, Elizabeth, can trace her roots here back to seventeenth-century Quebec. My parents, when faced with the choice of moving back to Hong Kong or staying in Canada to raise their family, decided to stay here. And our mixed-race family isn’t unusual: we live in the most multicultural city in one of the most diverse countries in the world, according to many metrics.

But my immediate thought was this: not even my children, my sweet, incredible children with their thirteen generations of Canadian ancestry, can escape this, can they? Because they’ll never look “Canadian.” Just like me.

The rise in anti-Asian discrimination during the pandemic had shaken my sense of my Canadian identity. But, at the same time, I had hoped my own children wouldn’t have as much difficulty navigating their own identities, given their mixed heritage.

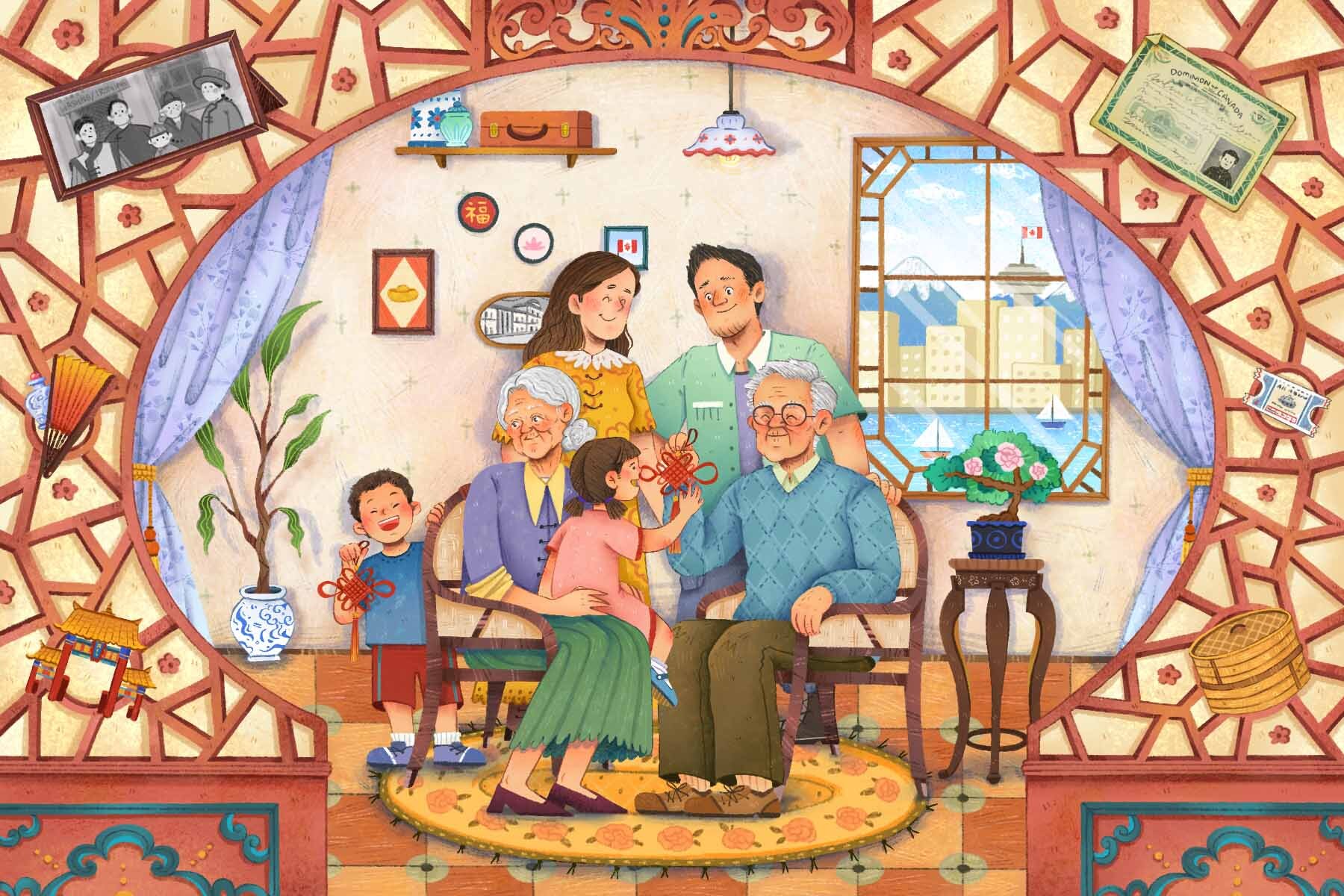

Then an idea came to me. For some time, my parents had expressed a desire to fly to Vancouver to visit friends and relatives they hadn’t seen in years. Let’s go too and take the kids, I suggested to Elizabeth. We’d go to Victoria as well. We’d take them to the oldest Chinatown in Canada. We’d take our kids to the school my dad went to. I wanted a photo of my parents standing with us and our kids in the place where, in a way, it all started for our family—a chapter of our story coming full circle.

On our first full day in Victoria, we stop by the idyllic St. Michaels campus, then explore Victoria’s Chinatown. It was established during the gold rush in the late 1850s but has been revitalized over the years. The red lanterns hanging overhead everywhere make the vibe a little touristy, but we love walking around this cluster of historic buildings and narrow passageways. My father says the buildings were much more rundown fifty years ago, with little investment happening in the community. He sees a marked improvement now. “Now this is a place I can take my son and my grandkids,” he says.

We make our way to Fan Tan Alley, which was notorious for its gambling clubs and opium dens. However, this was always the sensational side of the story, as the neighbourhood also provided much-needed refuge to the early Chinese pioneers, the vast majority of whom were men separated from their wives and families because of our laws. Today the place is home to a variety of shops and galleries selling everything from artworks to fancy soaps. But it’s also now home to a branch of the Chinese Canadian Museum Society of BC.

The museum is a significant reason I wanted our family to come out west. Founded in 2020, the CCM Society is a non-profit organization created as part of the province’s redress for the head tax and exclusion act. When we step into the museum, the kids are immediately dazzled by three fabric lion heads mounted on the wall, surrounded by black-and-white photos of Chinese Canadians who came before us. The featured exhibition, First Steps: Chinese Canadian Journeys in Victoria, traces the paths of the early Chinese in Canada and shows the history of the development of Chinatown, sharing stories of the people who built it up. As we’re about to leave, we take a family photo by the museum’s entrance, under an archway flanked by a golden phoenix and a golden dragon.

It’s a beautiful photo and a memento of a lovely visit. Yet, in my mind, this still isn’t the full-circle moment I had been hoping to experience. While I am certainly inspired by all the history, I can’t help but feel like I am just sightseeing. What I really want is to feel more of a connection. I am starting to wonder whether it will happen.

A few days later, we take the ferry to Vancouver to visit the largest Chinatown in Canada. We see the Memorial Monument honouring Chinese railway workers and war veterans. We have some amazing noodle soup for lunch. Then we reach the Chinese Canadian Museum’s Vancouver location.

The museum’s new permanent home will be the Wing Sang building. The historic Victorian structure was built in the late 1800s, making it nearly as old as Chinatown itself. This space will be the first national museum dedicated to Chinese Canadian history. At the time of the publication of this piece, the grand opening is scheduled for July 1, 2023, exactly 100 years after “Humiliation Day.” Maybe now that history doesn’t have to be humiliating anymore.

When we visit, the museum is operating out of a temporary space on East Pender Street. We explore three detail-rich exhibits about some of the Chinese Canadian community’s earliest leaders, getting a sense of their lives’ daily joys and struggles. I come across a glass case containing the gloves and helmet of Gim Foon Wong, an RCAF officer who, in 2005, at the age of eighty-two, rode his motorcycle from Vancouver to Ottawa to call for redress.

As we end our visit, I see my parents and my children standing in front of a giant map of the world. Visitors to the museum are invited to add a strand of string to show their journey to Canada from wherever they’re from. There seem to be thousands of strands all over the map, crisscrossing one another in every direction, originating from almost every country on Earth.

My mom pulls out a length of red twine. She and my father find Hong Kong on the map and lay their string across. They do it ever so gently, as if not to disturb the others already there. And there it is. That moment I had been searching for. The point of us coming out west wasn’t so I could see my family’s story come full circle. It was to remind myself that our story is a line, one that is unique but that also runs parallel to countless others. My identity as a Canadian is not static—it is complex and evolving and will likely forever be so. It is not merely about birthright or shared language but about engagement and seeking connection. Our pasts and futures—our pain and our promise—are not closed circles but lines interwoven together, like the collection of the strands on this map.

As we gather our things to leave, my mom cuts one more small piece of the red twine and tucks it into my daughter’s hand. I’m ready to go home.

In partnership with 100 YEARS LATER: The legacy of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Toronto Metropolitan University.