The original NieR was something of a cult classic that clued in many gamers into the fact that Yoko Taro is a genius — though people should seriously still look at the original Drakengard, which is good. The world at large became even more aware of Taro’s genius in 2017 with NieR: Automata, one of the best games of the past decade.

Yet the jump from NieR to Automata is not a journey from point A to point B, as much as people would like to think it is. Because the missing link between the two that is too often overlooked is at least half the reason Automata is as good, and successful, as it is. That missing link is 2013’s Drakengard 3.

The Drakengard/NieR franchise is a tough nut to crack. The franchise all stems from the original Drakengard, which was followed by Drakengard 2 (without Yoko Taro) and then Drakengard 2 (which is a prequel). NieR is a spinoff/sequel to one of the many endings of Drakengard, and Automata is a distant sequel to NieR. Did you follow that? What is important to remember in the context of Drakengard 3 is that it is a prequel to the original Drakengard and was released between NieR and Automata.

The Drakengard series is much more complicated and messier than the NieR titles. It is much more difficult for players to wrap their heads around, not to mention that the games are full of friction that makes them not fun to play by many people’s definitions of fun. So why after the cult hit that was NieR would Taro return to Drakengard?

It’s impossible to know exactly, but looking at Drakengard 3 in the context of what came before and after paints a picture of a game used to experiment and test the limits of what players would accept — narratively and mechanically.

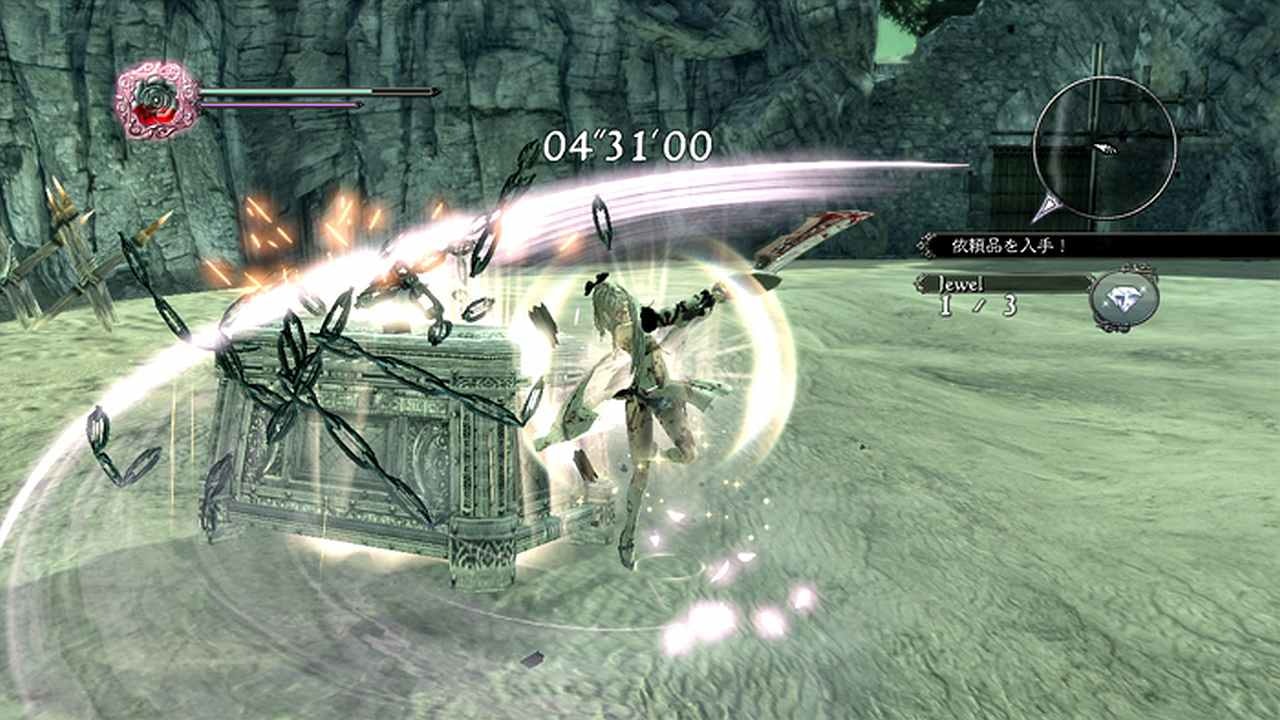

Drakengard 3 takes elements common in all of Taro’s games and dials them up to 11. Blood and gore are extremely prevalent as is the topic of sexual desire. It’s a depressingly dark story while also having one of the weirdest senses of humor in any game to date. The gameplay is smoother than the Drakengard games that came before but it is still frustratingly unwelcoming to the player.

All of this is most evident in my personal favorite part of this strange sexual comedy: protagonist Zero. She’s the first female protagonist in the Drakengard / NieR series. She hates literally everybody in the game’s party, hates the mission she is on, and breaks the fourth wall and talks about how she hates the repetitive combat and janky platforming. She’s just not happy to be anywhere. She’s a pessimistic protagonist for one of the more pessimistic games in Taro’s catalog.

Yet the story slowly chips away at Zero to reveal an impressively complex character, one that mirrors the impressively complex game that is Drakengard 3. Within Drakengard 3 are glimmers of something else. The spark of greatness that isn’t part of this game, but will turn into a full idea in Automata.

To some, Drakengard 3 is a bad game. But it is so aware of this that the question arises if it is a bad game on purpose. Again, the experimentation feels like Taro openly trying to challenge what a game can be, only to turn the quiet genius of Drakengard 3 into some of the biggest strengths of Automata. This can be seen in the game’s world, which pulls as much from NieR’s post-apocalypse as it does Drakengard 3’s battle-obsessed culture.

And then there is 2B. The reserved and stoic android protagonist of Automata whose personal journey of introspection becomes the beating heart of the game. 2B could not exist without Zero. They are two sides of the same coin, like Drakengard 3 and Automota. One side is defined by experimentation and pessimism and the other by refinement and optimism.

A decade later, even with the post-Automata popularity of Taro, Drakengard 3 has been pushed to the side of history as a bad game in between better titles. But if you revisit it, you might find yourself understanding Automata better than ever before.