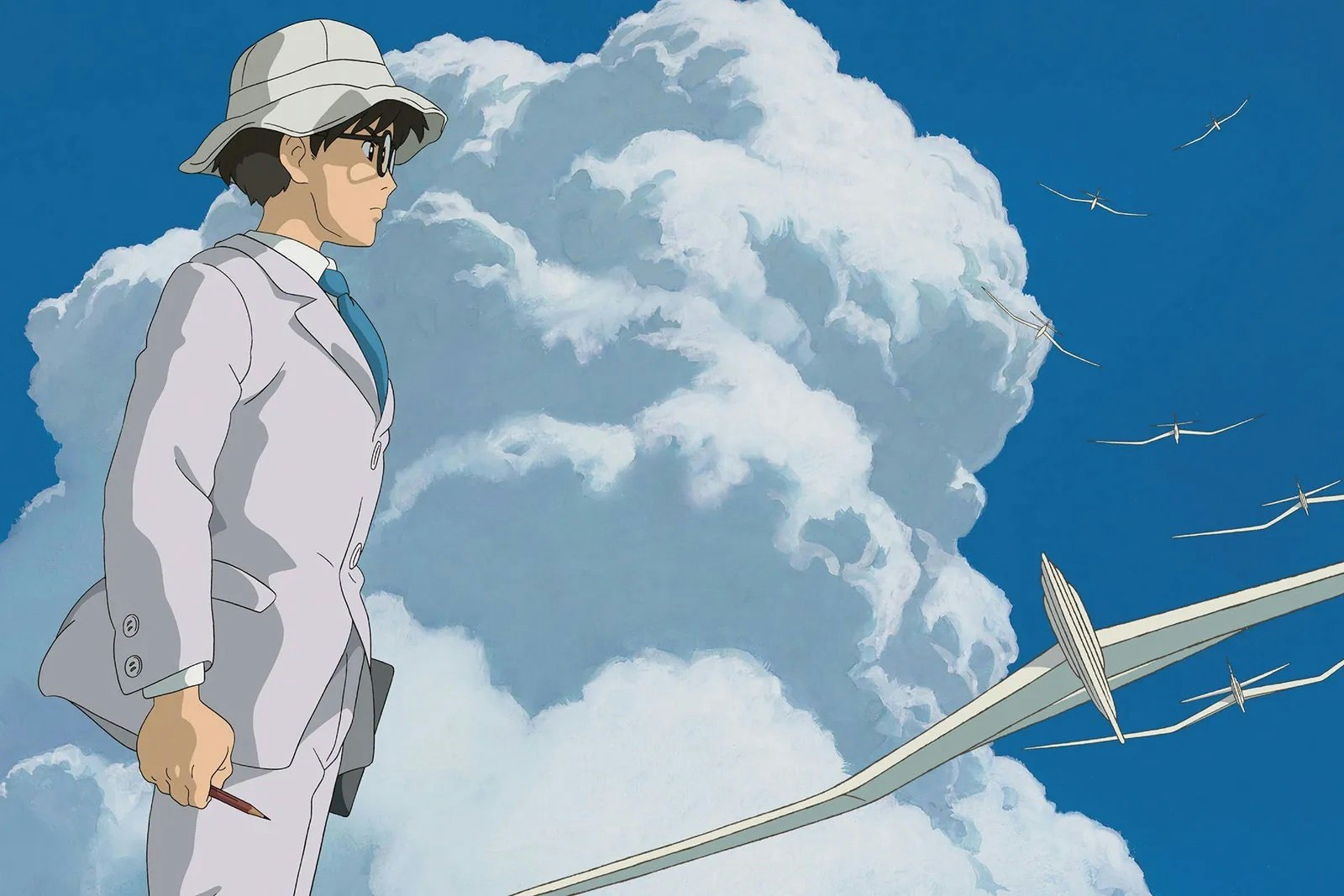

Jiro Horikoshi dreams of planes. They zip and soar through his mind, the images projecting on top of his head like a translucent, holographic vision. It’s a childhood dream that leads the young man to become Japan’s leading aircraft designer of the 1940s, and to become the protagonist of Hayao Miyazaki’s most personal film.

Released in 2013, The Wind Rises was advertised as Miyazaki’s final film, an epic and ambitious culmination of his entire career. Which is why many were surprised, and perhaps a little deflated, when he released a fairly straightforward biopic. The movie follows Jiro Horikoshi, the chief engineer of the Mitsubishi Zero, the fighter plane infamously used for kamikaze attacks in World War II.

Apart from Jiro’s frequently recurring visions of the planes he dreams of designing or the Italian designer that he admires, The Wind Rises notably is devoid of the fantastical whimsy of Miyazaki’s usual works. It’s grounded and, at times, even a little grim. Some might even (wrongly) call it dull. But the exquisite magic of The Wind Rises is how it peels back Miyazaki’s own legacy, allowing him to unpack everything that made him the filmmaker he is today.

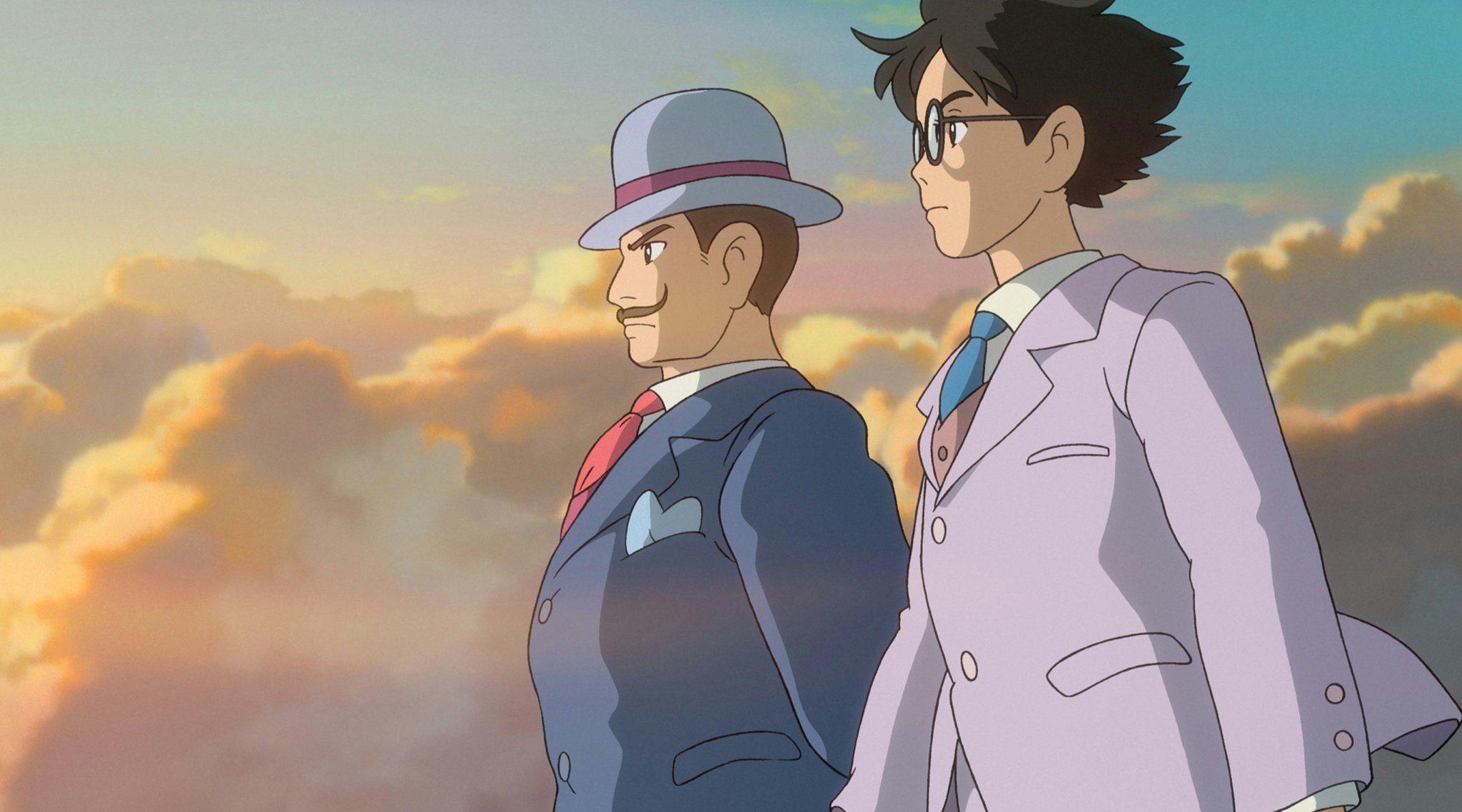

When The Wind Rises begins, Jiro is a young boy who dreams of being a pilot, but whose nearsightedness won’t allow it. So he sets his sights on designing planes instead like his idol Giovanni Battista Caproni, with whom he frequently has conversations in his dreams. “Airplanes are not tools for war, they are not for making money. Airplanes are beautiful dreams,” Caproni tells Jiro. But throughout The Wind Rises, Jiro’s dreams of only creating beautiful airplanes are rudely thwarted by reality, which requires him to contribute to the coming world war. The parallel is not hard to draw between Jiro and Miyazaki himself — Miyazaki, who only wanted to create these incredible fantasy worlds, reckoning with a reality that has reduced his work to marketable IP. What has his career wrought? Was it worth it? The state of the movie and anime industry might seem bleak, and the endless fight for creative integrity may feel hopeless but, as Jiro states in The Wind Rises, “the wind is rising… we must live!”

By making this kind of introspective film, the director ended up preceding an ongoing phenomenon in Hollywood. Filmmakers like Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, Pedro Almodovar, and most recently, Christopher Nolan, have all released movies that act as sort of encompassing magnum opuses for their careers. The Irishman, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Pain and Glory, and Oppenheimer are the kind of self-reflective projects filmmakers make toward the end of their careers. But Miyazaki got there first, and unexpectedly, he would make his coda to it a decade later.

The Boy and the Heron is just as intensely personal and revealing a film as The Wind Rises, but it’s like a photo negative to it — maximalist where The Wind Rises was minimalist and fantastical where the 2013 film was grounded. The noble Jiro was an of ideal surrogate for Miyazaki, but his latest protagonist, Mahito, embodies all of Miyazaki’s darkest and most unseemly tendencies. The Wind Rises is a crucial companion to appreciate The Boy and the Heron, the latter of which even more closely draws parallels to Miyazaki’s life — Mahito, like a young Miyazaki, has a father whose successful manufacturing company for World War II fighter planes never sat right with the young pacifist.

The Wind Rises, while a more formal, emotionally distant film (albeit one with some of Miyazaki’s most strikingly muscular animated sequences), gave Miyazaki an opportunity to really explore his own failings. In his single-minded pursuit of beauty, did he accidentally ignore the casualties that his career produced? Did he build his empire off of a foundation built by war profiteering? They’re ideas he explores to an even harsher degree in The Boy and the Heron. But they’re laid out from the beginning in The Wind Rises, which remains one of Miyazaki’s most underrated movies, and his elegant, intimately revealing magnum opus.