Around 10% of underground tunnel workers in Queensland could develop silicosis, our new study has found.

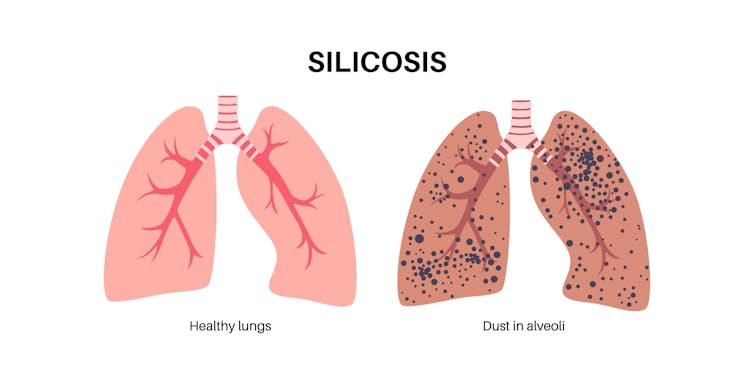

Silicosis is a serious, incurable lung disease caused by inhaling small particles of silica dust. You might have heard about it in people who work with engineered stone. But silica is more widespread.

Silica is found in rocks and concrete, so workers in industries such as construction, mining and tunnelling are at high risk if proper safety measures aren’t in place.

When silica dust is breathed in, it gets trapped in the lungs, causing inflammation and scarring. Over time, this scarring makes it harder to breathe and can be fatal.

As symptoms of silicosis can take decades to appear, workers may not realise they’re sick until long after they’ve started working, or even after they stop.

But silicosis is preventable.

How does silicosis affect tunnel workers?

Thousands of people are involved in tunnelling projects in Australia.

Tunnelling involves breaking up large amounts of silica-containing rock with heavy machinery.

Tunnel workers rely on advanced ventilation systems to provide fresh air underground, water systems to keep the rocks wet and suppress dust, and they wear respirators on their face to keep the air they breathe clean. But some people have raised concerns these measures do not always work properly.

There are also national legal limits in place for silica dust exposure, currently 0.05 milligrams per cubic metre over an eight-hour work day.

However, a media investigation last November revealed one-third of air monitoring tests from a Sydney tunnel project were above legal limits.

While air monitoring tests are required by law, the results of routine air monitoring tests are often not made public.

An expert taskforce has recently been set up in New South Wales to address the silica-related health risks for tunnel workers, promising to make high silica results above legal limits publicly available.

But while attention has been focused on tunnel workers in Sydney, the problem of lung disease in underground workers is more widespread.

Our Queensland study

The results of air monitoring tests are important because they show whether legal silica dust limits are being adhered to.

Another valuable use of this data is it can help us predict future disease risk. Instead of waiting to see how many workers develop silica-related diseases such as silicosis and lung cancer, this data can be used to estimate cases in advance.

In 2017, a Queensland parliamentary inquiry raised concerns about the health of Brisbane’s tunnel workers, particularly regarding the harmful effects of exposure to silica dust.

We worked through the parliamentary inquiry documents to uncover the results of hundreds of individual air monitoring tests conducted on three major Queensland tunnel projects between 2007 and 2013.

We analysed this data to estimate how many workers were exposed to silica dust and at what levels. We then modelled how many cases of silicosis and lung cancer would occur over the workers’ lifetimes.

We estimated that in a group of around 2,000 workers involved in these Queensland tunnel projects, 200 to 300 would develop silicosis over their lifetime as a result of silica dust exposure (roughly one in every ten workers).

We also estimated between 20 to 30 workers would develop lung cancer due to their exposure.

We had limited information on workplace conditions in the specific projects, so we made a number of assumptions based on publicly available information and our own experience. These included assumptions around the use and protective nature of masks. The fact we had to make some assumptions could be a limitation of our study. Due to the lack of data transparency we don’t know if these figures apply more broadly to tunnel workers throughout Australia.

Our projected rate of silicosis, 10%, is the same as the rate of silicosis recorded by a government inquiry in 1924 which investigated silicosis among workers who built Sydney’s sewers.

So it doesn’t seem things are any better in terms of silicosis risk in underground work than a century ago.

We need to do more to protect tunnel workers

Continued secrecy around silica dust data reduces our ability to understand the scale of the problem and respond effectively. Nonetheless, the small amount of data that has been made available supports the need for urgent action.

With Australia’s ongoing infrastructure expansion, policymakers must act now. This should include enforcing stricter legal limits for silica dust exposure. There is concern among health experts that current limits don’t sufficiently protect workers’ health.

Policymakers should also ensure protective measures such as advanced ventilation and dust suppression systems are in place for all tunnel projects, set up national tunnel worker health surveillance, and make exposure data available to workers and the public.

There are several examples where things are done better. Internationally, Norway and Switzerland have strong systems to protect tunnel workers’ health such as air and health monitoring being conducted by an independent government agency. In Switzerland, this agency also insures the project. Noncompliance results in higher insurance premiums or, in some cases, the withdrawal of insurance, effectively stopping the project.

Nationally, Australia’s mining industry is more heavily regulated than tunnelling, with stricter enforcement of compliance.

Without immediate intervention, thousands of tunnel workers will continue to face serious health risks and Australia will face a growing wave of preventable occupational diseases.

Kate Cole receives higher degree by research funding from The University of Sydney; is a member of the Asbestos and Silica Safety Eradication Council; the NSW Dust Diseases Board; the Chair of the External Affairs Committee for the Australian Institute of Occupational Hygienists; and acts as an expert witness for law firms concerning silica-related diseases in tunnel workers.

Renee Carey has previously received funding from the Australian Council of Trade Unions. She is a member of the Occupational Lung Disease Network Steering Committee formed by Lung Foundation Australia.

Tim Driscoll has acted as an expert witness, and written government reports, in relation to silica exposure but not specifically connected to tunnelling. He chairs the Occupational and Environmental Cancer Committee of Cancer Council Australia and chairs the Occupational Lung Disease Network Steering Committee of Lung Foundation Australia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.