Foxes kill about 300 million native mammals, birds and reptiles each year, and can be found across 80% of mainland Australia, our devastating new research published today reveals.

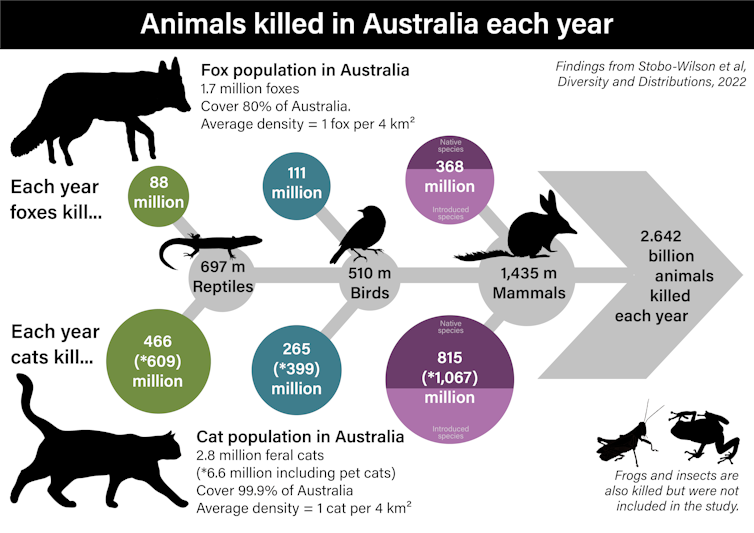

This research, the first to quantify the national impact of foxes on Australian wildlife, also compares the results to similar studies on cats. And we found foxes and cats collectively kill 2.6 billion mammals, birds and reptiles every year.

This enormous death toll is one of the key reasons Australia’s biodiversity is suffering major declines. Cats and foxes, for example, have played a big role in most of Australia’s 34 mammal extinctions, including the desert rat-kangaroo which rapidly declined once foxes reached their region.

Australia must drastically scale up the management of both predators, to give native wildlife a fighting chance and to help prevent future extinctions.

Australia is home to 1.7 million foxes

European colonisers brought foxes (and cats) to Australia. From 1845, foxes were released into the wild in Victoria for the “sport” of hunting them on horseback with a pack of hounds.

Fox populations soon exploded, thanks to the deliberate introduction of rabbits and hares in the 1800s. Rabbits and hares are not only a food source for foxes, they also eat the vegetation that native animals need for food, habitat, and to hide from predators. They continue to boost fox numbers today.

Our study estimates there are now 1.7 million foxes in Australia, spread across 80% of the mainland and on 50 Australian islands. They’re largely absent from tropical northern Australia and Tasmania.

By comparison, cats occur over more than 99.9% of the country, including on far more islands.

Fox densities are highest in temperate mainland regions, including forests and farms, and near urban areas where food and shelter are abundant. The Victorian government estimates there are as many as 16 foxes per square kilometre in Melbourne.

What are foxes eating?

The 300 million native animals that foxes kill every year consists of:

reptiles: foxes kill 88 million reptiles each year, and all are native. They’ve been recorded killing 108 different species – or 11% of all Australian reptile species – including the tjakura (great desert skink) and loggerhead turtle

birds: foxes kill 111 million birds each year, and 93% of these are native. They’ve been recorded killing 128 species – or 18% of all Australian bird species – including the mallee-fowl and little penguin

mammals: foxes kill 368 million mammals each year, and 29% of these are native. They’ve been recorded killing 114 species, or 40% of all land mammal species and half of all threatened mammal species. This includes the mankarr (greater bilby), quenda (southern brown bandicoot) and warru (black-footed rock-wallaby).

Foxes also kill another 259 million non-native invasive animals every year, predominately house mice and rabbits. They also kill livestock, such as lambs, piglets and chickens.

While rabbits and house mice form a major part of fox diets, there’s no evidence foxes (or cats) limit their numbers. Changes in rabbit and mice populations are largely driven by climate fluctuations.

Our findings are underpinned by modelling data assembled from almost 100 field studies. This included 49,458 fox poo and stomach samples, and fox density estimates at 437 locations.

Foxes are also known to eat bird and reptile eggs, and threaten the breeding success of many turtle species. However, we didn’t tally their impact on turtle eggs (or on fish, frogs or insects) because of insufficient data - they’re highly digestible and often hard to identify in fox poo.

Carrion (dead animals) account for an average of 10% of fox diets, but we excluded carrion in the estimated numbers of animals killed.

Foxes and cats: a deadly combination

Although they eat many of the same species, foxes take larger prey than cats and have a bigger toll on kangaroos, wallabies and potoroos.

Cats eat smaller prey, so eat a lot more of them. Nationally, feral cats kill about five times more reptiles, two and a half times more birds and twice as many mammals than foxes.

In total, feral cats kill 1.5 billion animals every year (not including invertebrates and frogs). Pet cats kill another 500 million animals.

Read more: One cat, one year, 110 native animals: lock up your pet, it's a killing machine

The impacts of both predators are concentrated in some regions more than others. And although cats kill more animals overall nationally, in some areas foxes take a greater toll.

This includes the Warren and Jarrah Forest in Western Australia, the Eyre and Yorke Penninsula in South Australia, across Victoria and in NSW’s Blue Mountains.

This is why foxes take a larger toll on forest animals such as possums and gliders, and kill over 1,000 animals per square kilometre each year in these areas.

To understand and manage these threats, it’s essential to take the cumulative impacts of both introduced predators into account. Many species fall prey to both cats and foxes.

Each day across Australia their combined death toll includes 1.9 million reptiles, 1.4 million birds and 3.9 million mammals.

So what needs to change?

The only way to stem these losses, and prevent the extinction of many vulnerable species, is to step up targeted and integrated cat and fox management.

Cat and fox eradication programs have had success in fenced areas and on islands. For example, cat eradication on Dirk Hartog Island is enabling many native animals to be reintroduced.

And long-term broad-scale management programs have enabled the recovery of threatened species in wider landscapes, such as the Bounceback Program helping yellow-footed rock wallabies and other wildlife in SA’s Flinders Ranges.

Our new research highlights the urgent need to increase investment for cat and fox management across Australia. Management will need to be large-scale and strategically coordinated as both species breed like rabbits, so to speak, and travel great distances.

This means patchy, or small-scale lethal programs can allow their numbers to quickly rebound.

We also need to protect and recover habitat for native animals. Evidence shows good habitat supports healthier native animal populations and gives them more places to hide from predators.

Read more: The mystery of the Top End's vanishing wildlife, and the unexpected culprits

23 scientists contributed to the research described in this article. The research received funding from the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub (which ended in Dec 2021). Jaana Dielenberg previously received funding from the Threatened Species Recovery Hub but does not currently work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article.

Brett Murphy receives funding from the Australian Research Council. He received funding from the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub (which ended in Dec 2021). He is a member of the Australian Government's Threatened Species Scientific Committee.

John Woinarski is the director of the Australian Wildlife Conservancy. The research received funding from the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub (which ended in Dec 2021).

The research received funding from the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub (which ended in Dec 2021).

Alyson Stobo-Wilson and Trish Fleming do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.