Sitting in a lake teeming with wildlife, several hours by train from Seoul, Korea’s Legoland is an unlikely poster child for the global struggle to fight inflation while maintaining financial stability.

But a default on 205 billion won ($155 million) worth of debt by the theme park’s developer triggered the worst meltdown in South Korea’s 1,690 trillion won credit market since the global financial crisis. And as interest-rate hikes batter real estate markets around the world, it’s a reminder that even relatively safer financial systems like Korea’s — labeled “resilient” earlier this year by the International Monetary Fund — face threats of contagion.

Korea’s central bank embarked in August last year on one of the earliest rate-hike cycles in the world, and is still battling inflation that at one point reached the highest level in more than two decades.

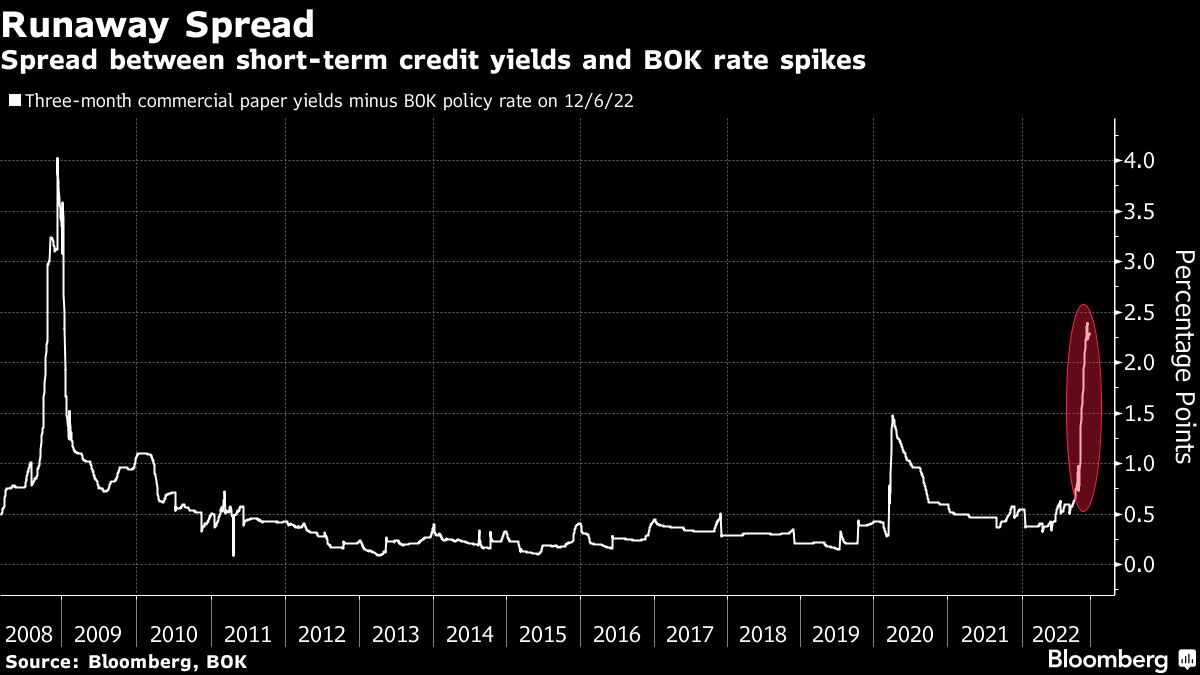

The default by Legoland’s developer was the first major sign of trouble in the local debt market. The shock sent short-term credit yields soaring.

Korea “is absolutely a canary in the mine shaft,” said William White, a former chief economist at the Bank for International Settlements, who for decades has stressed the dangers of super-low interest rates. Countries “tightening after such a long period of inviting leverage and imprudent financial behavior — you could potentially trigger the crisis that you’ve been trying to avoid.”

Back in May, Legoland opened to great fanfare. Featuring Lego-brick replicas of Korea’s most famous landmarks, it’s the first major globally branded amusement park to launch in the country. For Gangwon province, a mountainous and relatively underdeveloped region that has struggled with debt since hosting the 2018 Winter Olympics, the launch came as a welcome opportunity to reboot its pandemic-hit tourism industry.

But on Sept. 29, newly elected Gangwon Governor Kim Jin-tae missed payment on the debt for the Legoland project, borrowed by Gangwon Jungdo-development Corp. The municipality is the developer’s largest shareholder, in a deal created under Kim’s predecessor and political opponent. The refusal of a government entity to honor a debt payment shocked money markets already under pressure from rising interest rates.

“One mistake by one province,” Bank of Korea Governor Rhee Chang-yong said, holding up a forefinger, in a Bloomberg TV interview on Nov. 25. “That really shook up the confidence.”

As short-term credit yields skyrocketed, authorities in Seoul pledged billions of dollars in support for financial markets. While that’s helped staunch the meltdown, yields in the short-term money market remain near 14-year highs.

Even before this, Korea had the building blocks of a full-blown crisis: There’s been a run-up in household indebtedness and prices for apartments declined. Such developments preceded the US subprime crisis in 2007. And close to Korea, China has been stung in the past two years by an unprecedented property debt crisis, as defaults surge to a record.

“They are the two major Asian economies that experienced a notable rise in corporate debt” relative to economic output, said Ma Tieying, an economist at DBS Group Holdings Ltd. “This indicates their relatively high vulnerability to interest rate shocks or income shocks, which could stem from global liquidity tightening and export recession.”

The type of financial engineering in the Legoland developer’s default is called project finance asset-backed commercial paper, or PF-ABCP. The market for such securities has an estimated value of about 35 trillion won, and is a key source of funds for the broader Korean property sector. Brokerages back some of these securities, and their exposure to real estate project finance, on average, amounted to 39% of their equity capital at end-June, according to BOK data.

About 11.3 trillion won of such instruments are due to mature by the end of 2022, according to BOK data as of December 2.

Click here for a timeline on how Korea responded to the credit crunch

The default in this case was by the developer of the theme park, not the operator run it. They are separate entities.

“LEGOLAND Korea Resort remains open and is operating as normal” said the operator Merlin Entertainments, who runs the Korean park along with nine other Legoland resorts around the world. “The debts have no direct impact on the LEGOLAND Korea Resort, its finances or any operational running.”

Both the developer and Gangwon province declined to be interviewed for this story.

BOK Governor Rhee insisted the stress is confined to the short-term debt market and that the financial system remains in good health. But the ripples are still being felt.

In Gangwon’s capital of Chuncheon, home to the park, restaurant owner Han Man-jae is bracing for fallout as rates rise.

“As you know, interest is getting doubled so I’m a little bit worried about that,” he told Bloomberg Television in late November.

“I think all debt has to be paid back,” Han said when asked what he thought of the nationwide debt rout that had originated from his city. “What the governor said was that the case impacts other companies.”

Korea’s experience in the past few decades has left it particularly sensitive to the dangers of corporate defaults.

A spate of bankruptcies that triggered an International Monetary Fund bailout in 1997 has cast a long shadow over the country’s economy, as did the soured construction loans that felled a bevy of non-bank depository institutions in 2011.

That’s all left the nation’s policymakers more willing than most to make dramatic interventions, as they support a local credit market that quickly went from one of the world’s safest to teetering on the brink.

In the wake of the default in Gangwon, officials moved to staunch the blowout in yields with measures including a more-than-50-trillion-won aid package for markets, changes to collateral rules to boost liquidity and bank purchases of commercial paper, as well as additional project financing guarantees.

The flurry of steps has in recent days led to some signs of a recovery in the local credit market, as bond spreads tighten and yields on short-term debt plateau.

“Our take on Korea’s larger-than-expected market stabilization fund is that it likely is ample to address the latest credit strains in the short-term money market,” said Kathleen Oh, an economist at Bank of America Corp. “The biggest hurdle for local policy makers to recover credibility in the credit market is the current macro backdrop. As long as high inflation persists, the Bank of Korea will have to pursue contractionary monetary policy, tightening financial conditions.”

Gangwon’s Governor Kim also eventually relented, saying the province would repay the commercial paper repackaging loans no later than December 15.

Despite all the measures, yields on commercial paper — which companies use to raise funds for short-term payments like payroll — remain near the highs hit after the developer’s default.

Moreover, the risk of a spillover across Asia came into focus when a relatively obscure insurer Heungkuk Life Insurance Co. announced it would skip a call option on its perpetual note, triggering a selloff of such securities across the region. It later reversed the decision.

“At this point, we view the events of the past month as having been largely contained, given still-low delinquency rates and favorable interest coverage ratios,” said Anushka Shah, senior credit officer at Moody’s Investors Service. “That said, risks remain, stemming from spillovers from project finance-linked loans in the ABCP market to broader corporate debt.”

Officials in Korea told Bloomberg they have prevented the crisis from spreading.

But the developments underscore just how much of a balancing act authorities around the world face as they grapple with an economic downturn, and a war and energy crisis in Europe, with debt metrics higher now than in 2008.

At 96.9% of gross domestic product, the amount of credit to non-financial corporations across Group of 20 economies is now higher than in 2008, according to BIS data. For Korea, the ratio has shifted to 116.5% from 95%.

“The margin for action is very, very limited,” Nouriel Roubini, the economist renowned for foreseeing the mortgage collapse that helped produce the 2008 financial crisis, told Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast earlier this year, speaking of economies generally.

Although inflation was high in the 1970s, “this time it’s going to be worse because of the financials and the debt problem. So unfortunately at this point, damned if you do, damned if you don’t. There is no easy way out,” he said.

--With assistance from Whanwoong Choi, Daedo Kim, Jaehyun Eom, Hooyeon Kim, Julie Masuda, Andy Hung, Emily Yamamoto, Takaaki Iwabu, Catherine Bosley and Kathleen Hays.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.