He called it his last supper.

On the evening of 21 0ctober 1966, Martin Aleida arrived at a house in Central Jakarta with 50 sticks of satay, to be shared with five friends. He had spent the previous week plastering walls and fitting pipes to light a house. His wages went partly to this satay, bought at the Pasar Baru shopping area.

At that last supper in Mangga Besar, there was no drop of wine or bread, only leftovers. What was present was Putu Oka and the people he gave safe-housing to and the 50 bamboo sticks that remained of the satay.

Martin 2020:15

Afterward, all six were to sleep in the house. Martin was preparing to bed down on a divan in a back room, when a thin, asthma-stricken man appeared in front of him, brandishing a knife.

“Where are the others, Lan?” Burhan Kumala Sakti snarled. (Nurlan was Martin’s original name, before he changed it to Martin Aleida in 1969.) Martin recalled that he and Burhan had jointly monitored the broadcasts of Radio Republik Indonesia (RRI), the state-operated radio service, from all regions, in the first week of October 1965. Once a member of the national committee of the Pemuda Rakjat, the youth wing of the Communist Party of Indonesia (Partai Komunis Indonesia, PKI), Burhan had become a military interrogator, selling out his former comrades.

The six were bundled into a waiting vehicle, with soldiers in green jackets, covering their rank markings, standing by.

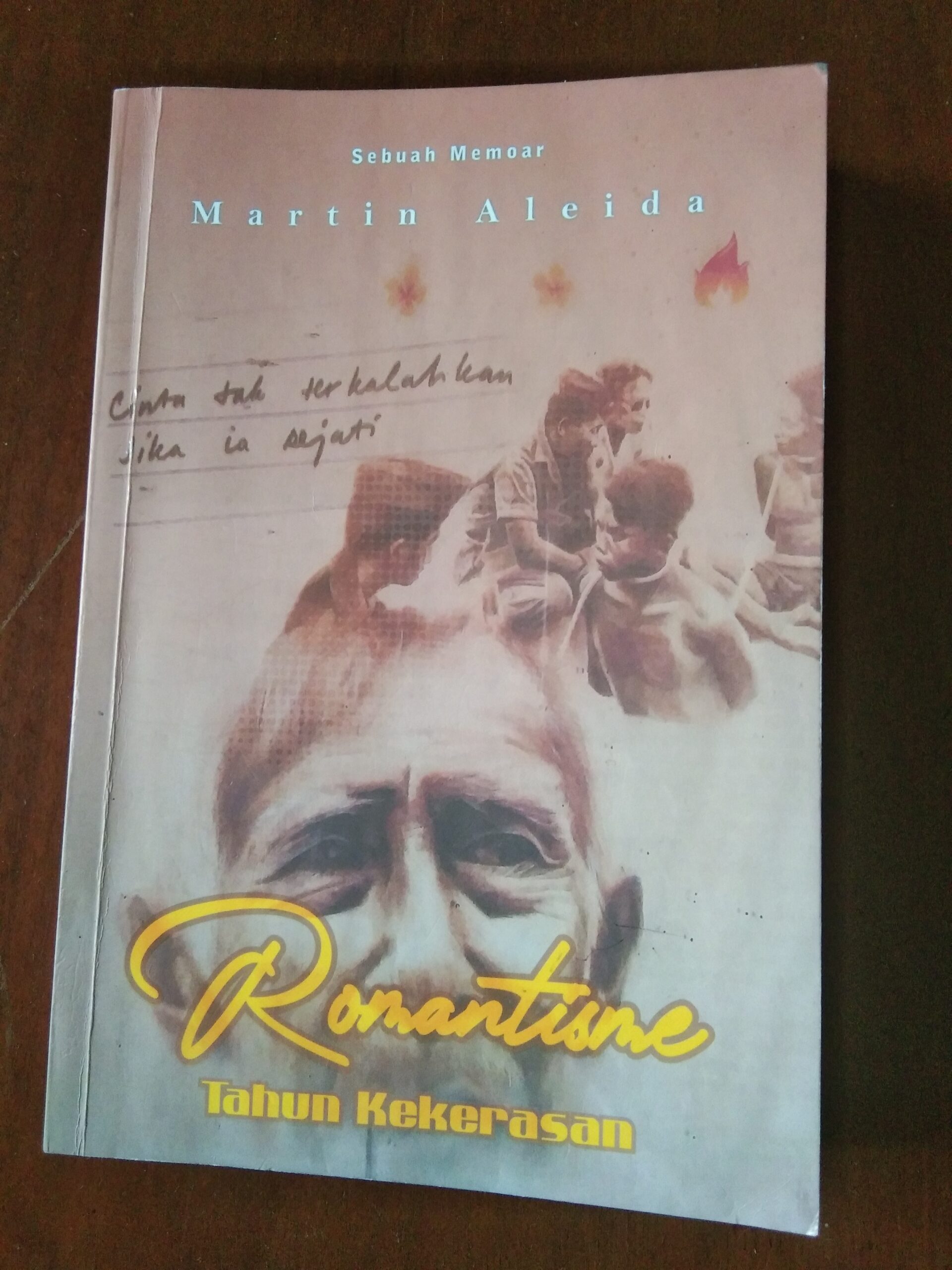

This episode is recalled in the newly published Romanticism in the Years of Violence, a Memoir of Martin Aleida. The book, written in Indonesian,[1] gives the account of a reporter sucked into the tempest of major course-changing events in Indonesia’s political history—the tale of a small cog caught in the turning of big wheels. Martin, now 76, recounts how he rose from copy boy to palace reporter, became an outcast as a political prisoner, and then, after release, rose and recovered his dignity as a journalist and award-winning writer. He is an eyewitness of momentous happenings: the intrigue inside the media organ of a major political party, and life in a political detention centre.

The memoirs are conversational and non-chronological, with Martin’s experiences as a reporter and his post-prison years interspersed with episodes from his life as a political prisoner, held without legal charge or trial. Martin’s richly descriptive narrative chronicles the fortitude of a fugitive on the run, treachery, injustice, oppression, violence, strength of character, high morals, human goodness, self-remaking, resurgence and well-weathered, lasting love.

Political detention

Martin and his five friends were suspected of involvement in the Gerakan 30 September (G30S, 30 September Movement), the failed coup attempt of 1 October 1965, which has been blamed on the PKI. On the night of 30 September 1965, squads of armed troops under the orders of Lieutenant Colonel Untung, a battalion commander in the regimental Tjakrabirawa presidential guard, fanned out to the houses of six targets in Jakarta: six generals, including army commander Lieutenant General Achmad Yani, were abducted and assassinated.

The next morning, Lieutenant Colonel Untung announced on national radio station RRI that the movement was to save President Sukarno from a takeover by a dewan djenderal (council of generals) and that a revolutionary council had been set up.

But Army strategic reserve commander Major General Suharto, a hawk-eyed general the conspirators had ruinously ignored, stopped the 30 September Movement that very night. Historian John Roosa, in a 2006 book, posited that Suharto used the movement as an excuse—a cloak—to smash the PKI and gradually enfeeble President Sukarno.

They (the army leadership) needed a pretext. The best pretext they hit upon was an unsuccessful coup attempt that could be blamed on the PKI. The army, in its contingency planning, had already drawn up a game plan: blame the PKI for an attempted coup, begin a full-scale war on the party, keep Sukarno as a figure-head president, and incrementally leverage the army into the government.

Roosa 2006:176-177

At that time, PKI was a formidable political party, claiming two million members. It was the first communist party in Asia and the world’s third largest, after those of China and the Soviet Union. But after the failed G30S coup, the army got the upper hand, hounding the party and associated mass organisations. Between 500,000 and 1 million Indonesians were murdered in the brutal aftermath.

Raids to root out suspected communists continued long after the coup failed. The Mangga Besar house raid, over a year later, was Operasi Kalong (Operation Flying Fox), undertaken by the intelligence unit of Military District Command (Kodim) 0501, Central Jakarta. It took into custody Putu Oka Sukanta (active in the leftist writers’ association of Lembaga Kebudajaan Rakjat (LEKRA, the People’s Cultural Institute), as well as keeper of the Mangga Besar safe-house), Arifin (a painter), Mujio (a house helper), Zaini (a high school pupil and younger brother of painter Marah Djibal), T. Iskandar A.S. (a reporter with the left-wing nationalist Bintang Timur daily and acclaimed author), and Martin Aleida, then known as Nurlan (a reporter with Harian Rakjat or People’s Daily, PKI’s party organ).

The group was taken to a military detention centre on Jalan Budi Kemuliaan in Central Jakarta. On the south side of the street lay the compound of Kodim 0501’s Section 1 (the intelligence department). It was behind what is now the immense premises of Bank Indonesia, the central bank. Its grounds could fill five football pitches. On the north side of the street were the buildings where the detainees were housed.

Early Education and Journalistic Beginnings

Born on 31 December 1943 in the coastal town of Tanjung Balai in North Sumatra, Martin is the son of a building materials trader. His father bought sago palm roofing and dolken wood, a type of wood from mangroves, for sale to rubber plantations outside the city of Kisaran, 25 km from Tanjung Balai. His shop, named Toko Baru (New Store), also sold cement and rice.

Martin had a knack for language. In junior high school, he won a declamation contest by reading out a Chairil Anwar poem on Diponegoro, the 19th century Javanese prince who had waged a five-year war (1825-1830) against Dutch colonial rule, only to be captured and imprisoned in solitary exile after a duplicitous invitation to talks held at a house of the Dutch command’s choosing.

In his first year at high school, Martin learned about LEKRA, the den of PKI-sympathetic writers. The next year, he wrote short stories that Harian Rakjat printed in its culture section. This Jakarta morning daily would arrive in Tanjung Balai, 150 km from the provincial capital of Medan, by the afternoon of the same day.

After finishing high school, Martin set off for Jakarta in December 1962, with his mother’s blessing but not his father’s. His mother’s parting words were, “Don’t forget to pray.”

He got in touch with notable left-wing writers and LEKRA members T. Iskandar A.S., Agam Wispi and S. Anantaguna, names he was familiar with from their work at Harian Rakjat. Martin’s first job was as a secretary and student at the Multatuli Literary Academy. A co-founder of the academy and LEKRA lead figure was Pramoedya Ananta Toer, the prolific, internationally acknowledged novelist, the lion in the den. (Pramoedya did not escape the subsequent military dragnet: he too had a ten-year stay on the remote penal island of Buru in the Maluku Islands).

In 1963, after several months at the academy, aged 19, Martin applied to be a reporter at two publications. Nationalist daily Merdeka ignored his application, while Harian Rakjat (HR) took Martin in. HR had a large circulation and influence, with a print-run of 2,000 copies in 1951. Daily circulation rose to 58,000 by 1956 and peaked at 85,000 copies by 1965 (Hill 1994: 29-30), in a nation with a population then nearing 100 million.

The Jakarta newsroom had 30 journalists. The paper did not have regular correspondents in the provinces, but had contributors (pembantu chusus). Overseas, HR had correspondents in Moscow, East Berlin, Beijing, Tokyo and Hanoi (to cover the war in Vietnam from the North’s perspective).

Harian Rakjat in the Political Landscape

The big picture in Indonesian politics in the early 1960s centred on the heated rivalry of the two major power players working to influence Sukarno and gain his favour. He was the unchallenged Pemimpin Besar Revolusi (great leader of the revolution), who had declared Indonesia’s independence on 17 August 1945 and remained president ever since.

Importantly, an incident in Madiun, East Java in September 1948 led to lasting resentment of the PKI on the part of the army. Musso, a PKI leader who had returned after 12 years away in the USSR, called for Indonesia to get close to Stalin’s Soviet Union. He fatally miscalculated when on radio he challenged Sukarno’s authority, calling for a fight to the finish (Ricklefs 1981:217).

After his long absence, Musso did not realise that Sukarno had broad public support. He was killed on 31 October 1948, in a clash with republican troops loyal to Sukarno. The army questioned why Sukarno would not outlaw PKI for its act of rebellion, but the remaining party leadership split up in hiding, only to regroup in 1951.

HR was significant for its role in this political landscape. Njoto, chair of its editorial board, was also number three in the PKI pecking order, as second deputy chairman of the central committee. The party chairman was D.N. Aidit and the first deputy chairman was M. H. Lukman. These three, together with third deputy Sudisman, were the youthful new generation of the politburo, who revived the party in 1951. At that time, Aidit was 28 and Njoto was 26 years old. In Indonesia’s first parliamentary general election in 1955, PKI emerged the fourth largest party.

President Sukarno appointed Njoto as a state minister without portfolio. He became a speechwriter for the president in addition to having his own column in HR, Tjatatan Seorang Publisis (Notes of a Publicist), under the pen name Iramani, the name of his younger sister. His front-page editorials for HR were in constant polemical battle with non-communist papers, particularly the nationalist non-party Merdeka (Freedom) daily, especially regarding Sukarnoism.

Martin recounts a story he heard from Sitor Situmorang, chair of the Lembaga Kebudajaan Nasional (LKN, National Cultural Institute), the cultural wing of the leftist Partai Nasional Indonesia (PNI). In a meeting with Sukarno, a leader of the PNI youth wing reportedly asked the president which interpretation of Sukarnoism was true. “Njoto,” Bung Karno (Brother Sukarno) asserted (Martin 2020: 49).

Through its propaganda department (Departemen Agitasi dan Propaganda, Central Comite) headed by Njoto, PKI would frequently hold mass rallies, drawing from their labour, youth, and women fronts, against perceived foreign enemies of the state, who represented “Nekolim” (neo-colonialism, colonialism and imperialism). During this time of great Cold War tension between the United States and the Soviet Union, American-owned property and US affiliated institutions were frequent targets. The war in Vietnam was also a reason to rally against the US.

The party also attacked enemies within the state, whom they labelled capitalist bureaucrats, counter-revolutionaries, revisionists and the bourgeoisie. In effect, these were people who had liberal thoughts and an anticommunist bias, supporting private property ownership. “Capitalist bureaucrats” specifically referred to military officers assigned to state-owned enterprises. In the countryside, Barisan Tani Indonesia (Indonesian Peasants Front) cadres were deployed to march for land reform, accusing major plantations of taking away the people’s farmland.

PKI was on a political high from 1964 to 1965. The party had success in moving the president’s hand on two issues.

The first was Sukarno’s banning of the cultural Manifes Kebudajaan. This was issued on 17 August 1963 by a group of non-communist writers and poets, seeking freedom of artistic expression in response to the rising influence of LEKRA. In turn, LEKRA and PKI attacked this as elitist “universal humanism”—hence anti-nationalism and anti-people. The party and its supporting organisations called for the Manifesto’s prohibition (Taufik 2009:322), and Sukarno obliged them on 8 May 1964. Petitioners who worked in government lost their jobs, including literary critic H.B. Jassin, who was dismissed from the University of Indonesia.

Second, the communist presence made its mark on journalism as well. Djawoto, chief editor of the national news agency ANTARA, and Karim D.P., general chairman of PWI, the Indonesian Journalists’ Association, were influential PKI sympathisers. HR had companion papers with a common editorial outlook in the Bintang Timur, Warta Bhakti andZaman Baru, among others.

This caused consternation among non-communist newspaper editors. On 1 September 1964, they established Badan Pendukung Sukarnoisme (BPS, Body for the Upholding of Sukarnoism), to “disseminate the teachings of Sukarno in their purity (meaning free from Communist persuasion)”. Column writer Sajuti Melik wrote numerous pieces on Sukarnoism (Marwati & Nugroho 1984: 380).

The real aim of BPS was to counter PKI. For instance, in October 1964, controversy arose over remarks made by PKI chair D.N. Aidit on the subject of Pancasila, Indonesia’s national ideology with belief in the one and only God as the first principle. “If we are already united, Pancasila is no longer necessary as Pancasila is a unifying tool,” he stated, “Pancasila is a unifying philosophy, but each group has its own individual understanding of it.”

BPS-member papers jumped on this, with the Revolusioner daily condemning the remarks as “dangerous” and stating that, “Not only do we disapprove of it, we also condemn and revile this toxic statement.”

In a letter of response, Aidit accused the paper of “subversive” conduct in “distorting” his statement, a charge backed up by HR which claimed that “counter-revolutionary papers” had “agitated and poisoned the public” (Tribuana Said & D.S. Moeljanto 1983:54-55).

PKI and its allies charged that BPS was an agent of the CIA, claiming it sought to “kill Sukarno with Sukarnoism”. Under PKI pressure, on 17 December 1964 Sukarno banned BPS, and the information minister in February 1965 revoked the license of 21 newspapers that supported it, including HR’s polemical opponent, Merdeka (Abdurrachman 1980: 206). Further, PWI expelled all members allegedly involved with BPS, so that BPS members lost their jobs (Marwati & Nugroho 1984: 381).

In the wake of these successes, PKI put to Sukarno two major proposals that intensified their clashes with the army: Nasakomisation and the establishment of the Fifth Force.

Nasakom was a doctrine formulated by Sukarno, bringing together three major socio-political inclinations, represented by different political parties, to govern the country. These were the Nasionalis (nationalist parties), Agama (religious parties, e.g. Islamic and Christian) and Komunis (Communist party). Leaders from nationalist and religious parties already held Cabinet posts, but PKI’s Aidit, Lukman and Njoto were only state ministers without portfolio.

PKI wanted to hold ministries such as labour and youth. It called for the appointment of nationalist, religious and communist representatives to all kinds of bodies, ranging from the leadership of regional parliaments to the directorship of state enterprises (Crouch 1988:67). It also wanted to expand Nasakomisation in the military, by setting up advisory teams in the armed forces. The army rejected this.

PKI’s second proposal also hardened the army’s enmity. Aidit in January 1965 urged Sukarno to establish a Fifth Force, arming ten million peasants and five million workers (Crouch 1988: 87) to defend the revolution and carry on the struggle in Indonesia’s confrontation with Malaysia (Legge 1972: 379-380).

Sukarno (left) had accused the United Kingdom of masterminding the formation of Malaysia to corner Indonesia. An unruly mob burned the British embassy in Jakarta in response to the Federation’s creation in 1963. Yet this characterisation of Malaysia faltered when, two years later, a tearful Lee Kuan Yew announced Singapore’s departure from the union.

Apparently, Sukarno would not outright approve these two PKI proposals, for fear of embittering the army command. Moreover, he could not remove army commander Yani: the public and the officer corps admired the general for suppressing anti-Sukarno rebellions in Sumatra and Sulawesi in the 1950s.

This was Indonesia’s political landscape when Aleida joined Harian Rakjat in 1963.

Martin’s life inside Harian Rakjat

Aleida’s initial intent was to work in the paper’s youth section, but he started at the bottom rungs of the newsroom ladder, first as copy boy, then as proofreader. His first reporting job was to cover City Hall and the City Council.

In early 1965, less than two years after he joined, a full-fledged newsroom meeting took place at the new HR offices at Jalan Pintu Air III, not far from the Istiqlal, Jakarta’s grand mosque. Editorial board chief Njoto opened by presenting the political situation in unusual detail (Martin 2020:150). Then he announced that the absent Anwar Darma, who covered President Sukarno, would be promoted to Moscow correspondent. Martin, sitting in the back, was suddenly named as his replacement.

The appointment raised accusations of favouritism. Lilik Margono, who represented the People’s Youth, appeared disconcerted, Martin recalled (Martin 2020:151). Martin was not yet 22 and had no education in journalism; his understanding of politics was shallow. He had only one year’s experience covering the governor of Jakarta, the legislative City Council (DPRD GR Jakarta)—fulfilling invitations, appearing at news conferences and covering mass demonstrations against the United States and the United Kingdom, as well as the campaign against Malaysia. Njoto had also asked Martin to renovate LEKRA’s cultural magazine, Zaman Baru (New Age), and publish it in a more orderly manner, altering its newspaper form into a magazine format.

Interestingly, in July 1965, some time after Martin’s appointment, Njoto lost positions in the party and paper. Internal conflict led to his removal as department head of the party’s central committee:

From a number of parties and close friends, I heard since July 1965 Njoto was removed as head of the agitation and propaganda department in the central committee of the PKI replaced by Oloan Hutapea. That meant that automatically Njoto no longer penned the editorial and the “Tjekak Aos” (brief and substantive in Javanese) column, both on page 1 of Harian Rakjat. Also, he no longer wrote the “Wong Tjilik” (Little People) political barbs on page 3. “Tjatatan Seorang Publisis” (Notes of a Publicist), a Tuesday column using the name Iramani, the name of his younger sister, also vanished.

Martin 2020:46

Njoto, no dogmatist according to Martin, was marked by in-party critics as a collaborator with the bourgeoisie. His relationship with a Russian interpreter was used to discredit him (Martin 2020: 151-152). Later, during Martin’s detention, fault was still found with Njoto for Martin’s appointment:

When I was thrown into the Operation Flying Fox concentration camp, Juliarso, a foreign editor at Harian Rakjat, greeted me as I passed by him with bitter sarcasm, “Here he is, Njoto’s favorite kid”.

Martin 2020:151

Nevertheless, Martin set about covering Istana events. The company asked him to order a suit with Lioeng Tailor on Jalan Sabang, a favoured clothier of State Secretariat staff and ministries. Martin chose a dark brown woolen suit with elastic tie that he could roll up and put in his suit pocket.

One Palace story Martin covered was a 1965 meeting between US envoy Ellsworth Bunker and President Sukarno. Bunker failed to dissuade Sukarno from supporting North Vietnam in its war against US-backed South Vietnam. Martin personalised the story by describing Bunker’s appearance, leaving the meeting room crimson-faced (Martin 2020:157).

One major event that perhaps the entire HR news staff attended was the commemoration of PKI’s 45th anniversary on 23 May 1965, at the 100,000-seat Soviet-built main stadium at the Senayan sport complex, constructed to host the Fourth Asian Games in 1962. Martin witnessed the grandeur of this gathering, where President Sukarno heaped praise on party chairman Aidit, calling him “benteng dan banteng nusantara” (citadel and bull of the archipelago). ANTARA journalist Supeno, with his baritone voice—later exiled to The Netherlands until the end of his life—served as master of ceremonies. The mass event demonstrated PKI’s power and pride at its peak.

Another memorable experience was Martin’s face-to-face exchange with President Sukarno at a tea party for palace reporters in the back terrace of Istana Merdeka (Freedom Palace), looking over a spacious lawn.

“What paper?” Bung Karno insisted on knowing. This question directed at me by the Great Leader of the Revolution of the Indonesian Nation made me quiver.

“Harian Rakjat, Pak (Sir) …”

Bung Karno spread his smile around.

“So, Pak Njoto’s kid,” he burst in laughter.

My heart soared. It’s as if Bung Karno had introduced me to those present.

Martin 2020:150

Martin was also tasked with assisting Tetsuro Jamaguchi, Jakarta correspondent in for Shimbun Akahata (Red Flag), the daily organ of the Japanese Communist Party, accompanying him periodically as an interpreter. Jamaguchi lived on Jalan Surabaya, a leafy street in the upscale area of Menteng in Central Jakarta, in a house belonging to Samosir, general manager of HR. In contrast to lunches at the HR office—just rice with tahu tempe—the dining table at Samosir’s house often featured kakap (sea bass) and gurame (freshwater carp).

Jamaguchi filed a long report, with photographs, on a major demonstration in front of the American embassy. PKI Agitprop chief Njoto read the piece in Japanese script and praised the correspondent. But Jamaguchi was soon recalled to Tokyo and never heard of again (Martin 2020:56).

Nevertheless, Martin stayed on at the Samosir house. There, in late 1963, he met Sri Sulasmi, who eventually became his wife. Hailing from Solo, Central Java, Sri was the niece of Samosir’s wife Lasinem. She went to high school on Jalan Batu, Central Jakarta and was later caught in the detention too, spending two months at the same camp as Martin, cleaning up the blood-stained floor of the torture chamber after interrogations.

HR and G30S

On the night of 30 September 1965, Martin was in Semarang to cover a political discussion held by a tobacco labour organisation. He returned to Jakarta on 2 October, learning of the events of the past few days from RRI broadcasts and local papers. At the HR office, the only familiar face he saw belonged to Pak Kusen, the door keeper, and some office staff. Concerned for his safety due to HR’s ties with the PKI, Martin began his search for safe houses (interview 19 May 2020).

I drifted from one house to another (including a roadside gasoline vendor and fellow writer friends from hometown Tanjung Balai) until I was accepted by Putu Oka as a regular visitor at Jalan Mangga Besar 101 in the Chinese quarter several hundred metres from the Husada Hospital, also known as Yang Seng Ie.

Martin 2020:67

The HR editorial on 2 October expressed support of G30S, arguing that the event reflected discontent within the army. HR took this stand (Martin 2020:47)—the only paper to do so—even though the editor-in-charge should have known that the coup had failed the night before, when Suharto, then chief of the Army Strategic Reserve Command (KOSTRAD), made a declaration on national radio.

Who wrote this suicidal editorial? The army was quick to point to it as proof of PKI’s involvement in G30S. Martin was certain Njoto could not have written it, as it lacked his familiar writing style: urgency in word choice and sentence form, short sentences, and rich store of expressions.

Martin strongly believed the editorial to be the work of deputy chief editor Dahono, who was close to Oloan Hutapea, the agitprop chief instrumental in Njoto’s removal from positions of influence in the party (Martin 2020:47). Chief Editor Mula Naibaho was often away from the newsroom, including on 1 October, as Sukarno was grooming him to be ambassador to an Eastern European country.

Years later, Martin met up with Wahyudi, the paper’s labour editor, after the latter’s release from Buru, a penal island for political prisoners connected with the G30S. Wahyudi told Martin that he had been in the newsroom that portentous night, together with Muslimin Jassin, chief editor of Kebudajaan Baru (New Culture), a new daily. Close to the printing deadline, three men in army uniform came and asked that HR and Kebudajaan Baru not print the following day’s edition. The two editors asked them for an official letter from the Jakarta Military District Command to verify this command.

“They could not show a letter. So, we printed,” Wahyudi recalled. Wahyudi also asserted that he did not know who wrote the 2 October editorial.

Martin 2020:47

In response to G30S, there was a quick take-over of the RRI premises and the movement’s armed units were neutralised, leading to the purge of the once-potent PKI, its mass organisations, cadres and sympathisers. The army’s elite para-commando regiment, RPKAD, headed by Colonel Sarwo Edhie Wibowo, swept through the provinces of Central Java, East Java and Bali to quash communist strongholds. Some 500,000 perished.

Among the PKI leadership, Aidit fled from Jakarta to Central Java, only to be found and executed on 22 November. Njoto was shot on 6 November after attending a cabinet meeting. Lukman and Sudisman went into hiding in Jakarta (Crouch 1988:161).

In total, 200,000 political prisoners were taken, and divided into three groups. Group A were assumed to be directly involved in the movement, and tried in a military tribunal. Group B were classed as active PKI sympathisers, and brought to Buru island, which eventually held 12,000 detainees for up to ten years. Group C belonged to communist-linked mass organisations but had no functional authority; they were gradually released.

Life in Prison Camp

Martin describes the conditions of his detention following his “last supper”, in what he called “a concentration camp”, in some detail:

Two soldiers in green jackets each with pistols sticking out on their waist herded us like a gang of thieves through a barbed gate into a big, decrepit house. Under a weak electric light, we walked single file past a large room which I believe is the bathroom. A number of rooms arranged like classrooms were to the back. A corridor split the yard that was large enough for badminton. The corridor connected the bathroom to a large hall 20 metres by 15 metres. The main hall was covered in floor tiles with a faded blue, floral ornament. Three-metre high walls topped by barbed wire separated this hall from the free world.

Martin 2020:18

All belongings that came with the body were confiscated. My high school diploma and a will from my parents who left on the steam ship Arafat to go on the pilgrimage (to Mecca) were seized and never returned. Also my love letters from my girlfriend who became my wife. Even the remainder of my one-week wage for wall plastering that I used to buy the 50 sticks of satay, I don’t know which green pocket it went to.

Martin 2020:54

Martin shared a two-by-three-metre cell with Samosir, Special Bureau member Suherman, and film producer A.W. Sardjono. Bedding was a tikar, a plaited mat made from pandanus leaves (Martin 2020:102). They bathed using a faucet the soldiers also used to wash their cars. The resourceful Martin made a makeshift kiln from pieces of genteng (oven-baked clay-based tile roofing) he foraged, and used a margarine can to cook. The cell-mates cooked rice and any food packets they received from relatives who visited on Mondays and Thursdays.

Food was scarce enough that prisoners were joyful even to find a piece of stale ikan teri (anchovy), rolled on a few lumps of rice in a besek (a bamboo-woven box). Extra servings were out of the question, except when a camp detainee was moved to the prison in Salemba, Cipinang or Tangerang, or when a detainee was interrogated at another camp at the time rice was given out. Boiled long beans were the only vegetable, and overcooked worms the sole source of protein (Martin 2020:26).

No books or newspapers were allowed, except for the Qur’an and the Bible. However, detainees clandestinely received reading material through family visits, including works from Alexandre Dumas, Karl May and Agatha Christie. Avid reader Martin had a share in this.

Camaraderie grew among the detainees:

Group prayers at the camp in truth instilled closeness. Not only with God but with fellow-inmates. The Idul Fitri prayer to mark the end of the fasting month of Ramadan was held in the open space near the entry gate of the camp. Many participated, making the space for the bowing of the head to the ground very tight. The khatib (preacher) who gave the sermon was Nur Bakti, Harian Rakjat’s photo journalist. I was appointed the mu’azzin, the caller to prayer. Three times I bellowed praise of the greatness of Allah urging fellow detainees to come to the prayer, to come close to (God), not to beg for freedom, but to venerate the fate that He has written down.

After the prayer, I not only shook hands with Nur Bakti, he closely hugged me. He commended my voice and he appeared moved.

Martin 2020:95

Yet these bonds were sorely tested by the divisive experiences of interrogation.

Interrogations and Tensions

Interrogations took place in the dead of night, guards leading the prisoner across the street in darkness. The camp kept receiving new detainees, who faced continual interrogation, including members of CGMI (Consentrasi Gerakan Mahasiswa Indonesia, Indonesian Students Movement Concentration), PKI’s student wing.

Balinese poet Putu Oka, one of Martin’s comrades-in-arms from their satay night, was considered too important to be lumped together with other detainees. Placed in the HQ building, he could be called in quickly for interrogation without crossing the street. His ribs and backbone were whipped and electric shocks were administered on his cranial nerves (Martin 2020:37-8).

Interrogators found a piece of paper in his pocket with names on it, leading to the arrest of HR general manager Samosir and chief editor Mula Naibaho (Martin 2020:38).

Some associates of Samosir and others charged Putu Oka with betraying them in exchange for less severe torture. At first, this accusation spread widely, adding to Putu’s suffering. “In reality I don’t know how the Putu haters got hold of a billy-club to punish him to their liking that way,” Martin writes (Martin 2020:39). But Martin believed that Putu’s resistance and resilience cowed the interrogators and the algojo, who administered physical beatings. In revenge, they acted to humiliate Putu, forcing him to join the operation to snag Samosir (Martin 2020:40).

This story was suggested to Martin by the disclosures of a camp officer: Sergeant Major Uyan, the camp’s deputy commandant, known to detainees as Pak Uyan. He was depressed that torture victims were made to accompany the military operation to denounce their own comrades.

“Is this not double torture?” he asked, with his head down. “I don’t know how it feels if I were to do that. I don’t know what torture does he feel who was brought to catch his own friend.” While he named no one in particular, the detainees thought he was describing Putu.

Putu Oka Sukanta is still alive. In a phone interview, Putu, 81, said his interrogators criticised him for providing shelter to people in his house. He was imprisoned for 10 years in total.

Champion over Fear

HR chief editor Mula Naibaho also suffered interrogation. He was ordered to take his clothes off and kicked into a sitting position, his thin body repeatedly thrashed from the nape down, with the jagged whip-like tail of a stingray. Uyan observed from the side, amazed by the strength of will and physical endurance of the journalist. Naibaho did not cry out in pain at receiving electric shocks either. Afterward, he was made to immerse himself in a water tank in an adjacent room, and forced to eat a plateful of red chili peppers (Martin 2020:44-45).

At daybreak, Naibaho put on his clothes. Uyan escorted him back across the street and allowed a number of detainees to stand around “the journalist who wrote a journalism book with brilliant, adroit sentence-writing, had interviewed Ho Chi Minh and who enjoys French poetry” (Martin 2020:45). Among them was Martin:

I removed his shirt carefully so that the skin did not scrape off. Undried blood stained the shirt.

“What did they ask? The Harian Rakjat 2 October editorial?” I asked when he realised who I was, his former reporter.

“Sudahlah,” (Forget it), he replied in a low voice.

“You’re kids, you’re uninvolved. I take full responsibility.”

In hearing his words, I stopped the questioning, not wanting to aggravate the stinging pain he was in. He gave the final word on work he did not do. A true journalist with morals walking towards the hangman’s scaffold to end the battle. I welcomed his answer as the attitude of a true moralist, champion over fear, who took responsibility for a deed I am certain he did not do. He was not the writer of the 2 October 1965 editorial!

Martin 2020:46

After the torture, Naibaho was taken to sit in front of the door to the isolation room, near the main hall where the inmates were quartered. He was asked to turn his back as a man approached him with a handful of uncooked rice and a clutch of kencur: a reddish-brown root from the ginger family, used as spice or medicine. The man appeared to be whispering a prayer, before chewing the rice and kencur, and smearing the resulting mixture over the wounded skin of Naibaho’s back. Naibaho neither complained nor grimaced.

According to Uyan, prisoners were often interrogated again after a day or two, before the primitive ointment had even dried. If the victim refused to confess, he was given electric shocks and whipped again, deepening the open wounds (Martin 2020:50).

Toward the end of 1966, the camp held 200 political prisoners, out of a cumulative total of 500 detainees from October 1965. Some had been transferred to other centres. The interrogators regarded some 20 detainees as of high value in the uncovering of networks (Martin 2020:87).

Sujono Pradigdo, head of verification of the PKI central committee, was kept in a one-metre wide cell. A small field, strewn with red pebbles, separated him from a garage holding a dozen or more members of the party’s secretive Special Bureau, a network he had reportedly revealed to interrogators. This clandestine group had reported directly to Aidit. Its job was to infiltrate the armed forces and cultivate the officer corps, less to make them into party cadres than to orient them toward party thinking; this was in contrast to Aidit’s more open oratorical appeals to army personnel. Syam Kamaruzzaman, the Special Bureau’s enigmatic chief, later boasted it had been “running smoothly” in seven provinces. It had regular contact with 250 officers in Central Java, 200 in East Java, 80-100 in West Java, over 40 in Jakarta, over 30 in North Sumatra, 30 in West Sumatra and 30 in Bali (Crouch 1988:83).

Syam was taken into the camp in a Volkswagen appropriated from a detainee. He had a medium build with dark brown skin, and wore a peci (a Muslim velvet cap). Martin saw him twice, and noted that many believed him to be a double agent, responsible for the downfall of party chief Aidit, who had trusted him (Martin 2020:100). The Extraordinary Military Tribunal eventually sentenced Syam to death.

Green Sheet – Life After Detention

Sergeant Major Uyan stuck his close-shaven head through my cell door. “You’re called,” he said with a smile displaying his big teeth.

At the office of the Operation Flying Fox commandant, chief of staff Second Lieutenant Syafei asked me: “Lan, if we send you home, where will you go?”

“I don’t know. Probably to Gondangdia Lama Dalam where I boarded,” I replied.

Syafei smiled. I read his lips without words as if in mocking mode. It would be inconceivable to return to a house that had long been in surveillance. It was where Sobron Aidit, younger brother of D.N. Aidit, stayed before he left for Beijing in 1963 to be an Indonesian language instructor. Journalists, writers, instructors, teachers, staff of an organisation for Chinese Indonesians have long been left to live there to entrap them and bring them in at an appropriate time.

Syafei drew out a light green form sheet and ordered me to fill it. It was to be my official deposition. I wrote in my name, place and date of birth, occupation: Harian Rakjat journalist.

One question asked for the reason for detention. I left it empty. Syafei did not ask me why I left it empty. At the bottom of the form, vaguely in my mind, is the wording: not involved in “G30S/PKI”.

Martin 2020: 104-105

Former political prisoners carried a KTP, their resident identity card. In the bottom left hand corner stood the letters ET: eks tapol, former political detainee. Many tapols faced stigma, struggling to find jobs. Martin’s KTPs were not marked. He had not been, he says, a card-carrying member of the PKI or its mass organisations (interview May 2020).

One week later, I was called in again. Syafei said Rudewo, a fellow inmate who had been released earlier, would not object to accomodate me after my release (Martin was released May 1967, eight months after his arrest).

I was freed! I was the last of the four in the satay night last supper who were detained at the camp. Iskandar, Putu and Arifin had been moved to other prisons.

Martin 2020:104-105

Martin was never interrogated. He was merely asked about his work. A piece of paper found on him probably persuaded the interrogating officers that he was no menace. It was a will from his parents, identifying the property destined for each of their children, prepared before they sailed on pilgrimage to Mecca. But after his release, Martin had to report to the Kodim 0501 HQ once a week.

The only belongings he took out of the camp were two sets of clothing and a sarung folded in an old newspaper, tucked under the armpit. Martin left the detention centre and stood on Jalan Thamrin, a 12-lane main thoroughfare a five-minute walk away. He felt he had entered a bigger concentration camp. A prison with no border, enclosed by the sky (Martin 2020: 106).

He realised he had no friends. All had been apprehended. His first destination was Jalan Bahari in the Ancol area, North Jakarta, more than 3 km away. There stood a bamboo shack with fish ponds on either side: a house owned by Martin’s former employer Rudewo, who ran a printing business for which Martin engaged in proofreading.

After working for less than a year at Rudewo’s print works, Martin could no longer hold back his yearning to see Sri, 500 km away in Solo. He asked Kodim HQ for her home address (she too had been detained for two months). After an exchange of letters, Sri enthusiastically welcomed him to Solo. On his third visit, one year after his release, Martin and Sri got married, without the fanfare of a party.

In Tempo

Martin wanted to return to the world of writing. For this, he adopted a new name. As a reporter in HR, he had used his birth name Nurlan. Now he went by Martin Aleida. The first name was taken from Martin Luther, the 16th century Christian reformer. The second name, Aleida, is coastal Malay and roughly means an expression of awe and respect.

Ekspres, a new weekly news magazine, appeared in 1970, funded by Nurman Diah, son of the former ambassador to Thailand and Information Minister B.M. Diah. Djufri Tanissan, a painter friend, told Martin it was short on reporters. To get a job, Martin should see its chief editor, Goenawan Mohamad—a man two years older than Martin already making a name for himself in poetry and as a signatory of the once-illegal Cultural Manifesto.

Martin’s first assignment, from religion affairs editor Syu’bah Asa, was to report on the impact of loudspeakers on the solemnity of the five daily Muslim prayers. After a month’s work, Martin’s pay was IDR 6,000 (US$15.87 at the time). Not enough for a family with a child: Martin left the magazine.

Not long afterward, Ekspres was affected by a clash in the leadership of PWI, the Indonesian Journalists Association, prompting the departure of Goenawan and a group of journalists. They approached Jakarta Governor, Ali Sadikin, and property tycoon Ciputra to back a new publication. Tempo was born, with Goenawan its chief editor. Martin joined in January 1971.

The magazine grew quickly, and Martin’s track record grew with it. His first month’s pay was a much more attractive 10,000 rupiah. Tempo’s print run rose from 12,500 copies in 1971 to 151,000 by the early 1980s.

Martin covered numerous assignments, but not politics. Each edition had a word from the newsroom on how a news story had been written, and by whom. The news staff was obsessed with getting featured on that page, but Martin avoided it. He did not want to invite the attention of the powers that be.

However, a photo of Martin and fellow reporters Yusril Jalinus and Herry Komar eventually appeared. Martin received a letter asking him to report to an Operation Flying Fox office on Jalan Gunung Sahari III. On the desk of the interrogator was a copy of Tempo, opened to the picture. The cross-examiner, Sartono, a LEKRA man, wanted to know how a reporter for HR had landed a job with the popular news magazine.

Martin described his work since his release. The interrogation lasted for two hours, ending when the Operation Flying Fox commandant walked in, wearing a green jacket that hid his name and rank.

“Do I have to leave Tempo,” I boldly asked the commandant.

“No need. Continue your work. This is a good magazine. His voice was flat and his eyes were still fixed on Tempo. He then left Sartono and me, one of the many old comrades he (Sartono) betrayed, now his victim

Martin 2020: 193.

Martin had it good at Tempo. The company usually awarded staff members with ten years of service with a house worth 20 times their monthly salary: Martin got his house in less than ten years.

I have done my hardest to give the best to Tempo and it has given me back my lost world, words, journalism.

Martin 2020:216

Injustice and Fairness

Throughout his book, Martin constantly raises the injustice and legality of his detention, and that of his comrades.

They were tortured because they made a life choice to be members or sympathisers of a legal organisation. In my case as editor of an official cultural magazine Zaman Baru (New Age) and as reporter of a legal paper, Harian Rakjat. These are not clandestine, underground pamphlets. Civilization has truly been trampled on before the detainees who should be treated as political prisoners, as they were hurled into detention due to a political calamity.

Martin 2020:51

The “new culture” introduced by the order of militarism of general Suharto is the annihilation of communists and other progressives as enemies “down to their roots.” This call is constantly wailed by army officers more often than the five times (Muslim) daily call to prayer.

Martin 2020:38

With thousands of prisoners detained in camps and in prisons throughout the country, this state is no longer a state of law but a state of the condemned.

Martin 2020:115

Buru island is not only the problem of 12,000 souls isolated and tormented with hard labour. It was also the burial ground for the talents that fostered Indonesian culture within their individual ways and attitudes in life. I am fortunate with Tempo that opened its pages widely for what I can do, so far behind them whose minds and hands have been washed and handcuffed for more than a decade. Talent is fate. It can’t be pulverised even though the body is exiled with violence as an ever-present threat.

Martin 2020:226

Martin is equally sensitive to fairness. The government emptied the Buru island penal camp of its 12,000 detainees by 1979, freeing prose writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer after 14 years in detention. His semi-fictional four-volume history of Indonesia under Dutch colonial rule, Bumi Manusia (Earth of Mankind), was composed in Buru and has won world acclaim, enjoying a film adaptation in 2019.

On Pramoedya’s release, Tempo chief editor Goenawan Mohamad drafted a critical column on the writer, a leader in LEKRA and a steadfast supporter of Nasakom. Pramoedya had condemned the Cultural Manifesto as liberal and pro-West; Goenawan Mohamad was a signatory of that manifesto. He showed a draft piece—a little over half a page long—to Martin, who suggested that in the interests of balance, since Pramoedya was forbidden to reply, the draft should be shown to him before publication. Goenawan appeared to decide against publication, seemingly out of respect for the dignity of a man deprived of freedom of expression.

In June 1984, Martin left Tempo due to strife within the magazine, and became an information officer at the United Nations Information Centre in Jakarta.

Fiction and Non-fiction

Martin writes both fiction as well as non-fiction. In addition to two novels, he has written short stories for Horizon the cultural magazine, Jakarta entertainment magazine Matra, and in newspapers Kompas, Media Indonesia, Suara Pembaruan and Koran Tempo, with one story translated into French and English.

See: A Review of Homeland Lost by Warief Djajanto

The events of 1965 and the experiences of Indonesian exiles are the background of many of his short stories. For instance, Tanah Air—which in 2016 won Martin a short story prize and IDR 13 million (US$900)—is about an Indonesian exile in the Netherlands, who yearned to return home but could not do so. Depressed, he jumped from his 8th-floor apartment to his death. The police found his hand grasping soil from Indonesia bandaged in the red and white flag of his homeland. Similarly, his highly acclaimed 2017 book, Homeland Lost, describes the lives of exiles in Europe.

A Light Shone on a Dark Page

Martin Aleida lived through a dark chapter of Indonesia’s political history. He did not suffer the torment of physical abuse and banishment to a distant penal island. Nor was he stung by stigma of being a former political detainee to the same extent as others. But, alongside all caught up in the purges of the 1960s, he suffered injustice and unfairness. Martin was neither a card-carrying PKI member nor (he emphatically states) a Communist, yet he stood accused by implication.

His response to that perceived injustice has been to record and report, in his memoirs as well as in both fiction and non-fiction, the grim consequence of 30 September 1965.

His work has been his effort to fight forgetfulness and shine a light on that dark chapter.

For more, please see Warief Djajanto Basorie’s interviews with Putu Oka Sukanta and Goenawan Muhammad.

Martin Aleida: A Brief Bibliography

Martin Aleida is a prodigious writer of fiction and non-fiction that stem from personal situations of people affected by events linked to the 1965 30th September Movement. Below is a sampling of his works since his 1967 release as a political prisoner.

A collection of 17 short stories are in the book Leontin Dewangga (Kompas Media Nusantara, Jakarta 2003). The first three have the events of 1965 as the background.

Malam Kelabu (Grey Night) is the story of a youth from North Sumatra who travels to a village on the bank of the Bengawan Solo river in Central Java, to ask the hand in marriage of a local girl. He finds her family had suffered mayhem. A PKI fugitive was found in their house. The fugitive was chopped and the house burned down.

Leontin Dewangga (Dewangga’s Pendant) is about a young man from Aceh who is arrested after the 1965 affair for being a member of a communist-affiliated union in the film industry. He was saved by a letter from his father found in his pocket stating that he (the father) was going on the haj (Muslim pilgrimage) by ship.

The young man travelled to the Bungur area in Jakarta and met a young woman, Dewangga, who became his wife. The wife got stricken with cancer fighting for her life. The man went level with his wife to reveal his background as an ex-political prisoner.

Hearing her husband’s story, she asked him to open the pendant she was wearing around her neck. He opened it and found a picture of a red crescent, symbol of the peasant movement, of landless farmers taking unilateral action to seize farm land under the agrarian law. The pendant was given to Dewangga by her father before he disappeared in 1965 never to return.

Ode bagi Selembar KTP (Ode of a resident identity card) is the story of a woman who was imprisoned at a concentration camp for women in Plantungan, Kendal, Central Java. Stigma is made to last when people allegedly involved in the 30th September Movement carry resident identity cards (KTP) that has the ET lettering meaning they are former political prisoners. The woman sold a piece of land she inherited from her father. With the money, she bribed with millions of rupiah the village administration to get a KTP free of the ET marking.

In 2013 Martin published Langit Pertama, Langit Kedua (First Heaven, Second Heaven), a compilation of his essays, critiques, book reviews. It includes a 25-page take on Wars Within, a 2005 book on the Tempo story by American scholar Janet Steele, journalism professor at George Washington University.

References

Abdurrachman Surjomihardjo Ed. 1980. Beberapa Segi Perkembangan Sejarah Pers di Indonesia. Deppen RI, LEKNAS-LIPI, Jakarta

Crouch, Harold. 1988. The Army and Politics in Indonesia. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Hill, David T. 1994. The Press in New Order Indonesia. UWAP, Asia Research Centre on Social, Political and Economic Change, Pustaka Sinar Harapan

Legge, J.D. 1973. Sukarno, A Political Biography. Pelican Books, Suffolk

Martin Aleida. 2003. Leontin Dewangga, Kumpulan Cerpen. Penerbit Buku Kompas, Jakarta

Martin Aleida. 2003. Langit Pertama, Langit Kedua. Nalar

Martin Aleida. 2020. Romantisme Tahun Kekerasan, Memoar Martin Aleida. Somaling Art Studio, Jakarta Timur

Marwati Djoened Poesponegoro & Nugroho Notosusanto. 1984. Sejarah Nasional Indonesia VI. PN Balai Pustaka, Jakarta

Ricklefs, M.C. 1982. A History of Modern Indonesia. The Macmillan Press, Southeast Asian Reprint, Hongkong

Roosa, John. 2006. Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup d’Etat in Indonesia. The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, USA

Roosa, John. 2020. Buried Histories, The Anticommunist Massacres of 1965-1966 in Indonesia. The University of Wisconsin Press digital version

Taufik Abdullah. 2009. Indonesia Towards Democracy. ISEAS, Singapore

Tribuana Said & D.S. Moeljanto. 1983. Perlawanan Pers Indonesia BPS Terhadap Gerakan PKI. Penerbit Sinar Harapan, Jakarta.

Interviews online with Martin Aleida from 2 May to 26 May 2020.

[1]All translations from Indonesian to English are by the author.

The post Indonesia’s Years of Violence appeared first on New Naratif.

New Naratif explains and explores the forces which shape how Southeast Asians live and understand our region. Learn more at https://newnaratif.com/hello/.