China’s latest attempt at boosting its flagging birth rate is a crackdown on an expensive wedding custom. Few people — including officials themselves — expect the measure to make a difference.

Betrothal gift, or caili, is a tradition where the groom-to-be pays a “bride price” to the woman’s family to demonstrate his sincerity and wealth, while also compensating them for raising a daughter in a country that has long favored sons. Almost three-quarters of marriages in China involve the custom, according to a survey of 1,846 residents conducted by Tencent News in 2020. Families could be expected to pay tens of thousands of dollars, multiples of their annual income.

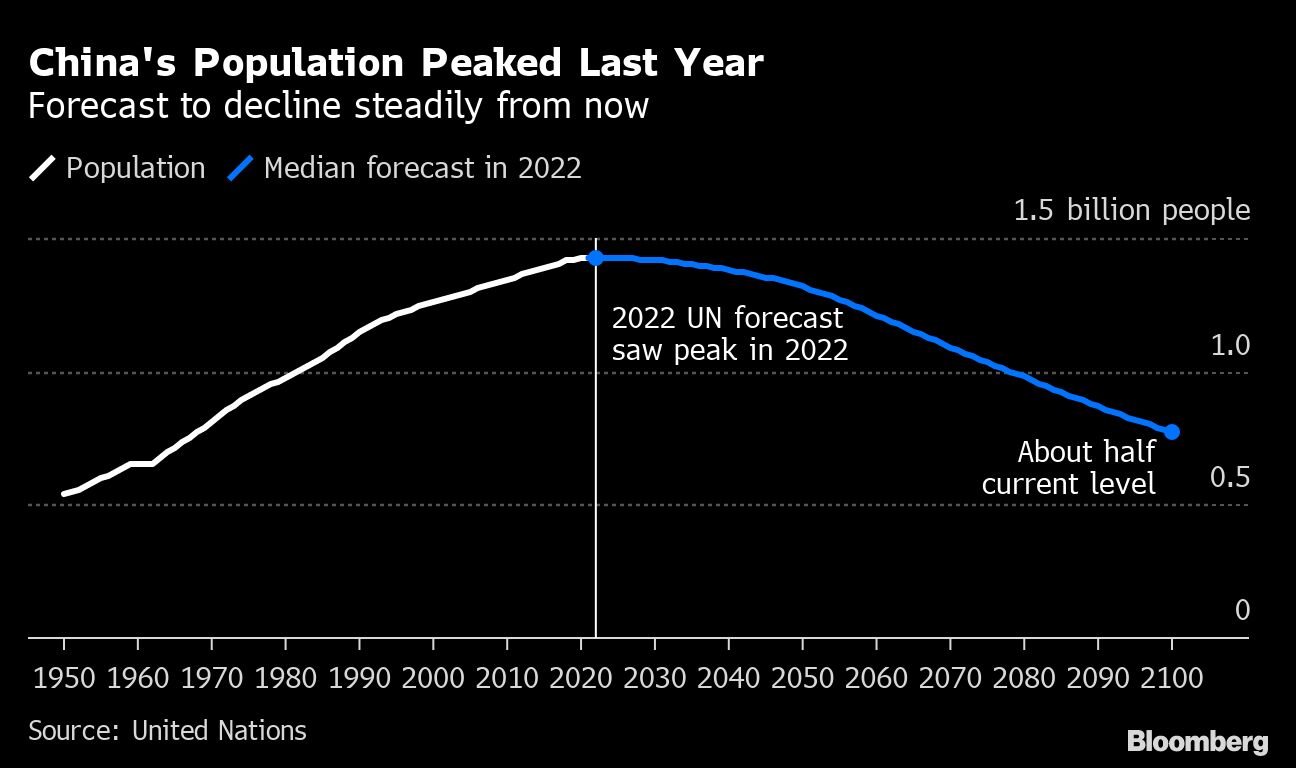

It isn’t the first time authorities have taken aim at the practice, which was featured in an annual central agriculture policy document this year for the third consecutive year, but there is now a renewed clampdown as China urgently tries to reverse its demographic decline. A faster-than-expected population drop-off means a shrinking workforce, falling consumer demand and growing strain on the health-care system.

Less than a month after China posted its first population decrease in 60 years, the head of the family development agency asked local governments to take “bold and creative” steps to encourage births. The increasing unaffordability of marriage, particularly at a time of slowing economic growth, is seen as one of the key reasons why fewer people are getting married and having children.

In January, central Hebei province started cracking down on what it called “ugly marriage traditions,” which in addition to caili also include crass wedding games. A county in coastal Jiangsu province kicked off a campaign last month to look for “the most beautiful mother-in-law” who doesn’t ask for too much money. A town in Jiangxi made single females sign a letter in February promising not to ask for caili that’s too high, while the provincial capital is holding a mass wedding on International Women’s Day with the slogan: “We want happiness not bride dowries.”

A series of other recent policy changes reflect China’s determination to raise the birth rate. Officials are increasing subsidies for newborns, promoting marriage leave for workers and even relaxing rules to allow unmarried couples to register their children. But these superficial measures tend to favor men, amid rhetoric from President Xi Jinping that encourages women to return to traditional gender roles while keeping women out of power at the top of politics.

“There is little hope to reverse declining births unless deep-rooted issues like gender inequality are addressed,” said Feinian Chen, a professor of sociology at Johns Hopkins University. With women still expected to be the primary caregiver, “the opportunity costs of having more children or having children at all are simply too high.”

The caili problem can be traced back to China’s one-child policy, which has led to a huge surplus of men. That gender imbalance means the bride’s family can often ask for higher prices. The bride’s family also often pays a dowry to the groom’s family, though authorities have not taken aim at that custom.

The issue is especially pronounced in rural areas where the gender ratio is more skewed. Earlier this year, internet users from villages in seven provinces aired complaints about unattainable financial demands on a government feedback portal. State media are also increasingly highlighting the marriage burden faced by families in rural areas.

Authorities are trying to frame the practice as an antiquated relic that needs to be retired, but changing people’s minds may prove to be difficult.

Betrothal gifts are seen as “a column of the wedding economy,” without which people may even lose the appetite to get married, said Kailing Xie, a lecturer in gender studies at the University of Birmingham. “It’s like using a band-aid to patch a problem.”

In an acknowledgment of the resistance in parts of their community, officials in Fujian province said their campaign against expensive caili is going to be a “persistent and difficult war.” A local official in Jiangxi conceded that a hard crackdown would be impossible.

In a city in Hebei, which officially started curbing expensive caili and other outdated traditions in 2021 as an example for the rest of the country, a village party leader admitted that families are still charging as much as 300,000 yuan ($43,343) for betrothal gifts.

“There’s no way that the village officials could control this, unless they can offer my son a girl to get married to,” said Wang Ling, whose son was asked to pay over 40 times his monthly salary to win the blessing of his in-laws. Wang stepped in and shelled out her entire savings to foot the 328,000 yuan bill.

“If the boy’s side can’t fork out any money, it’s off the table,” Wang said.

--With assistance from Yujing Liu.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.