A few years ago, I attended a federal court hearing about the Dakota Access Pipeline. The pipeline passed near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation and beneath a lake that is sacred to local bands of Lakota and Dakota people, and a protest camp had sprung up to block its construction.

At the time, in 2016, the pipeline story was one of the country’s biggest climate controversies. The Obama administration would go on to freeze the pipeline, before President Donald Trump revived it. (It is now operational.) But the courtroom, where the pipeline’s fate was ostensibly going to be decided, was largely empty. I was one of maybe a dozen journalists in the gallery; other than that, it was just the two legal teams and the judge. The only other young people in the room, besides me, were one of the judge’s clerks and an entire row of young lawyers seated behind the legal team—for the pipeline.

I thought of that experience this week as I read the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah’s recent “Ethicist” column in The New York Times. The column is addressed to an anonymous law student who is debating taking a high-paying job at a big law firm to pay down their student debt and help their family.

“The firm’s work entails defending large corporations that I’m ethically opposed to, including many polluters and companies that I feel are making the apocalyptic climate situation even worse,” the student writes. “Even if I only stay at the firm for a short time to pay off my loans, I would be helping in these efforts for some time … Will defending polluters, even for a short time in a junior position, be a permanent black mark on my life?”

Appiah does not give a resounding “no.” He recognizes that climate change is a real problem, but offers a series of justifications for why it might be okay to work for a company knowingly and intentionally making it worse. (None of them includes the standard—and most straightforward—reason to work for, say, an oil company, which is that people still want a lot of oil.) Because companies are required to hire good and experienced lawyers, Appiah seems to say, that means that you should not feel bad about working for one: “For an adversarial legal system to function justly, there have to be lawyers who are willing to serve clients they disapprove of.”

[Read: A hotter, poorer, and less free America]

His thinking gets more slippery from there. “Even if what your clients are doing is legal, you may still feel uncomfortable supplying guidance and representation, because the activities shouldn’t be legal,” he writes. “We ought to have laws and regulations that treat the climate crisis with full seriousness, and we don’t.” Yet he treats this problem—that the country’s climate policy, even after the Inflation Reduction Act, remains insufficient—as an unfortunate coincidence that has nothing to do with the behavior of companies or, indeed, their lawyers.

If the story’s headline asks “Is It OK to Take a Law-Firm Job Defending Climate Villains?,” the correct response is “probably not.”

Appiah’s biggest mistake is that he assumes that all lawyers are equally talented. But in fact, the quality of lawyering matters. For proof of this, you need look no further than the experience of one Donald Trump. The former president has perennially struggled to hire lawyers, both in a personal capacity and in his role as president. Four major law firms reportedly declined to represent him during the Russia probe in the early part of his presidency. His White House suffered from unprecedented staff turnover, including among its legal advisers. In energy and environmental policy, his administration regularly appointed people to senior roles who had far less experience than their equivalents would have had in an earlier Democratic or Republican administration.

And you can see this failure in Trump’s results, particularly on beyond-the-headlines policy questions. For instance, presidents normally win about 70 percent of their regulatory-law cases, The Washington Post has reported. But the Trump administration lost 78 percent of its cases, according to data from the Institute for Policy Integrity at the NYU School of Law. Having covered a few of these failures, I can attest that they usually stemmed not from the fact that Trump's administration was trying to do something illegal per se, but because his lawyers had failed to dot their i’s.

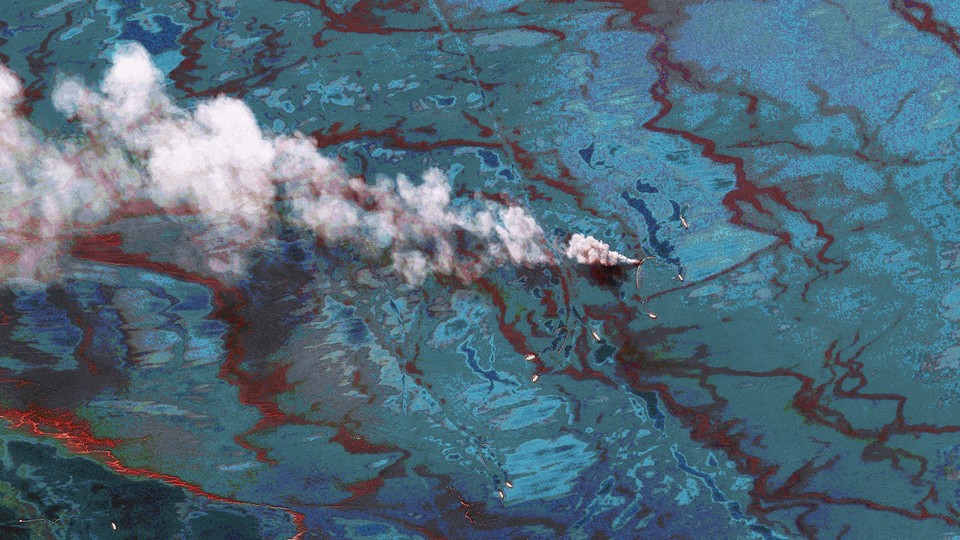

This made the Trump administration unusual, because malign actors can usually rely on all the assistance that the legal profession can offer. One of the open secrets of the American legal system is that some of the country’s most retrograde and malevolent companies rely on some of its youngest, most promising lawyers. Every year, a river of law-school graduates surges out of Cornell, Columbia, and Harvard and flows directly into the nation’s biggest law firms. Once ensconced at these firms, those promising young lawyers—many of whom championed progressive causes while in school—defend the world’s most egregious polluters, child-labor-law abusers, and tax cheats. That’s how a brilliant and idealistic 20-something with the world’s best legal education might find themselves fighting to build an oil pipeline beneath a sacred Lakota site.

No doubt that a young person in such a situation could find many ways to justify their own behavior. They might reassure themselves that everyone wants and needs energy, and that the energy business still remains in large part the fossil-fuel business, so the country needs more pipelines. Or they might say that they need to pay off law-school debt so that they can take care of an aging parent. Or they might protest that, as Appiah writes, “representing a malefactor isn’t, ipso facto, an act of malefaction.”

The point is that anyone can come up with many elegant, well-argued, and even correct justifications for their own behavior. (Coming up with excuses will, in fact, be the anonymous law student’s future job.)

[Read: Wall Street’s skirmish with Exxon is ‘monumental’]

What interests me about this question is that it forces each of us to ask where, exactly, we might draw the line. As the climate warms, and as the economy decarbonizes, we will all have to decide exactly what sort of behavior we find morally acceptable—and we will have to take note of the fact that “There is no alternative” can sometimes rapidly turn into “There is no excuse.” Right now, I live in a city with almost no street-side electric-car chargers, so I feel like I have no alternative but to own a gasoline-powered car. But one day, I’m sure, I will feel that it’s wrong to own anything but an electric car.

Likewise, I have no compunction about intercontinental air travel, even though it’s among the most carbon-intensive activities that one can do, because it’s a marvel of modern society and because there is no technological substitute for it. But will climate change one day get so catastrophic that I can no longer justify the carbon pollution?

Already, the calculus isn’t as simple as the student and Appiah make it out to be. The student probably does not have to work for an evil law firm anymore to pay off their loans: If they care about climate change, they could go work for any number of climate start-ups that are hiring and paying market-rate salaries. In economics, we have outgrown the idea that there is some trade-off between helping the climate and helping the economy. But the same is true of careers now too.

“We’re rightly concerned when corporations do damage to the environment, and so to humanity as a whole,” Appiah writes at one point. “But it’s hard to see how the world would be improved if such corporations couldn’t find legal advice and representation.”

On the contrary, I think it’s quite easy. If companies could not find lawyers to represent them when they do bad things, they would lose more lawsuits. This would cost them money, and discourage them from doing more bad things. Some questions are better suited to an accountant than an ethicist.