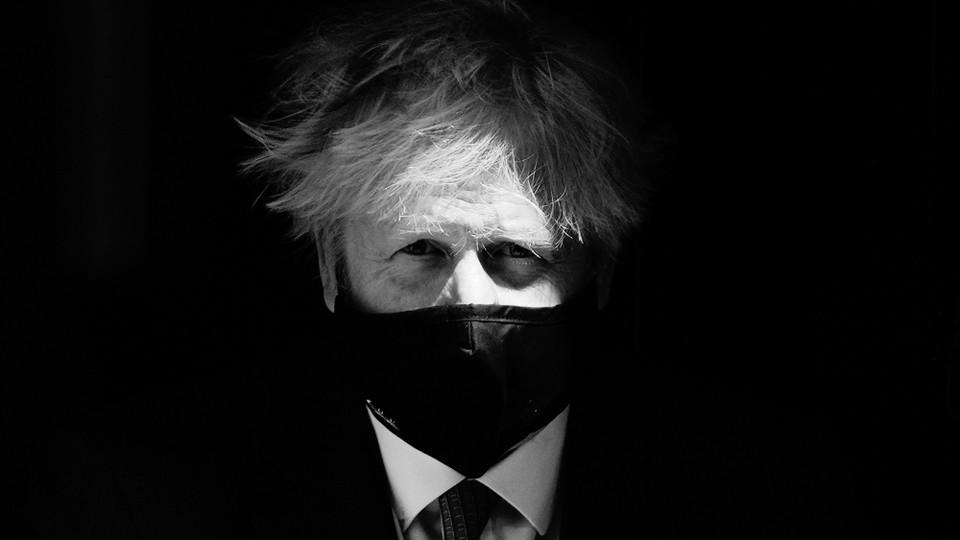

A few months ago, I saw Boris Johnson recount a story about his life that I’d never heard before—and he said something that was not, strictly speaking, true.

With most politicians, hearing a new tale can be unremarkable, but with Johnson—the subject of at least two biographies, countless newspaper and magazine articles, and someone who has been at the center of British political life for decades—almost everything that can be known about him is already known. Revelations that might once have troubled his ascent have long since lost their power to shock; character flaws are minimized in the public consciousness not through omission but through repetition.

On this occasion, the British prime minister was sitting in the atrium of Queen’s University in Belfast, talking to students and promoting his government’s new post-Brexit student-exchange program. As the conversation bounced around, one of the youngsters said they were thinking of studying in Australia. Johnson’s face lit up. He loves Australia and told the students he had once been a visiting professor of European thought at Melbourne’s Monash University. He then made a quip about the man who had invited him later being dismissed, adding with a laugh: “Other than that, it went well.” (Johnson has made this claim of a prior career in academia previously, in a 2011 speech and in one of his columns.)

I’ve followed Johnson my entire career (and wrote a profile of him this year), but the story about his professorial past was new to me. Andrew Gimson, one of his biographers, hadn’t heard about it either. Intrigued, I contacted Monash directly.

Johnson, it turns out, spent time at the university about 30 years ago. Yet he was not a “visiting professor of European thought.” He visited Monash on a two-week “professorial fellowship,” which involved a few classes, talks, lunches, and dinners. “He was here and gone,” says Brian Nelson, a professor of French at Monash who was there at the time, processed Johnson’s application for the role, and spent time with him during his stint in Australia. He told me that for Johnson to call himself a visiting professor of European thought was “somewhat self-aggrandizing.”

At first glance this looks like another clear-cut example of Johnson lying—or at best embellishing the truth. Was he a visiting professor? No, he was on a “professorial fellowship.” Does the distinction matter? Whether it does or not is central to the challenge of assessing Johnson, his relationship with the truth, and his skill as a politician. (A Downing Street spokesperson did not respond with a comment when I approached them about this story.)

To his critics, Johnson is a liar and a fraud, and stories such as this one are taken as further evidence for their case. According to his onetime rival for the Conservative leadership, Rory Stewart, Johnson is “the most accomplished liar in public life—perhaps the best liar ever to serve as prime minister.” Johnson, Stewart wrote last year, has “mastered the use of error, omission, exaggeration, diminution, equivocation and flat denial. He has perfected casuistry, circumlocution, false equivalence and false analogy. He is equally adept at the ironic jest, the fib and the grand lie; the weasel word and the half-truth; the hyperbolic lie, the obvious lie, and the bullshit lie—which may inadvertently be true.”

I thought about this recently when Johnson broke an election pledge not to increase taxes. Then, on a visit to New York City, he claimed that he had always been clear that Britain would struggle to reach a trade deal with the United States, despite having previously told voters that the ability to negotiate such agreements was one of the key benefits of Brexit. The story, in its most uncharitable telling, is this: In 2016, Johnson said Brexit would both save British taxpayers £350 million a week in contributions to Brussels—money that could be better spent on Britain’s National Health Service—and free up the country to negotiate a trade deal with Washington. After winning the referendum and becoming prime minister, Johnson promised there would be no tax raises on his watch. Then, this month, he announced Britain’s most significant tax increase in 20 years—to pay for an increase in health spending—before flying to the U.S. to be told by Joe Biden that he only wanted to talk about trade “a little bit.”

Despite this—and despite other Brexit-related issues, from product shortages at supermarkets to a brewing crisis in Northern Ireland, to say nothing of a disastrous early response to the pandemic—Johnson has lost little ground in the polls, and the Conservative Party appears on course for another decade in power. Johnson could well become Britain’s most consequential prime minister since Margaret Thatcher.

All of this raises a question: If Johnson really is such a liar, why don’t voters seem to care?

The political scientists Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes have developed a distinction between “accuracy” and “sincerity” to explain why voters seem to care little about the lies told by politicians they support. People can be “truthful” about two things, they write in their book, The Light That Failed—facts and feelings. Of the two, only the former is falsifiable.

In the case of Donald Trump, a populist leader to whom Johnson is often likened, the former American president’s most zealous fans seemed wholly indifferent to revelations that many of his comments were factually untrue. Why? “Because they believe that these statements are sincere, and thus ‘true’ in a deeper sense,” Krastev and Holmes write. Trump’s sincerity is based on what he represents and his commitment, by means fair or foul, to realize his goals. To his supporters, Krastev and Holmes write, Trump’s lies are sincere, because he has already said that the only thing that matters to him is winning, and they believe he is trying to win on their behalf.

In Trump’s worldview, winning is the be-all and end-all—for people and for nations—and anyone who says otherwise is either a dupe or a fraud. This applies to elections and the rule of law, as well as international relations and trade. All of this makes Trump a revolutionary figure, because he is the first U.S. president to reject the American-made world as bad for America. Unlike Biden and every other U.S. leader, Trump believes the free-trading, democratic world living peacefully under the American nuclear umbrella is a bad thing, because it allows free-riding competitors to undercut the U.S. Thus, America in this view is not exceptional; it is naive.

In contrast, Johnson is boringly conservative. He doesn’t believe Britain has been a victim of the postwar American order or even, really, of European Union membership; nor does he want a new world order. He just thinks Britain—and his own leadership aspirations—would, on balance, be better off outside the EU. Unlike Trump, Johnson sees a world of natural alliances of like-minded countries, historic civilizations, shared democratic norms and threats, and, of course, Western exceptionalism. Johnson is prepared to say many things to convince voters to support him, but even his fiercest (rational) critics do not think he would attempt a Trump-style insurrection to retain power if he lost an election.

Yet he does have similarities with Trump. While Trump shares few of Johnson’s romantic visions of history—partly because he doesn’t know any—both have a deep cynicism that helps explain their appeal. Johnson, like Trump, believes many of his opponents are insincere. “He doesn’t trust anyone,” a former aide once told me. “He thinks everyone thinks like him.” To the voters who believe all politicians are essentially liars and cheats out for themselves, Johnson’s obvious mockery and refusal to abide by the usual rules of political decorum—by, for example, telling what his opponents allege are lies—have an obvious appeal.

[Read: Boris Johnson and the Optimism Delusion]

Johnson himself also seems to believe that there is a distinction between deep truths and shallow facts. In his view, each story or historic event contains a fundamental truth—that Churchill saved freedom, say; or that British democracy is not compatible with the EU. Facts are tools used to tell this wider story, yet they are not as important as what Johnson holds to be the central truth.

The “lie” that Britain could save £350 million a week by leaving the EU enrages those who opposed Brexit—and who never believed the assertion in the first place. Yet this claim, which has become burned into the national consciousness, does not appear to stir the emotions of those who were apparently duped. Why?

If the Krastev-Holmes theory holds, it is because the fact never mattered much to the people who supported Brexit. What mattered was the principle: that the British government should spend less on the EU and more on Britain’s public services. Those who are outraged by Johnson and his £350 million statement are, perhaps, less angry about the claim than about its insincerity. They are angry because they believe it was used knowingly in pursuit of a deeper falsehood—that Britain would be better off outside the EU—or because of their sense that Brexit was about not money or democracy, but border control and immigration. Indeed, Anand Menon, a professor of European politics at King’s College London, told me that polling trends clearly show that hardly any voters changed their minds during the referendum campaign. The reason the Brexit campaign won is that it was better at getting its vote out than the campaign to stay in the EU was.

Johnson nevertheless faces a political problem. Some of those people who believed in Brexit and the sincerity of the campaign for it now face a triple whammy of Brexit-induced inflation, tax hikes, and rising household bills to pay for the shift toward renewable energy. It is easy to see how voters will continue to believe in Brexit itself but conclude that Johnson is no longer sincerely on their side, believing him to have prioritized other issues—post-pandemic economic recovery, the government’s efforts to tackle climate change, clearing the backlog faced by the health service—over their take-home pay. In other words, it is not the lie that will cost him, but the reality of people’s lived experience: their truth, if you will.

The problem with labeling Johnson an out-and-out liar is that the charge conceals far more than it reveals—rather like Johnson himself.

Again, let’s return to the infamous £350 million-a-week claim. This figure is dismissed by most serious observers as misleading and wrong, because it ignores rebates and reinvestments that significantly lowered Britain’s net contribution. However, Britain did pay more into the EU budget than it received, and arguing for that money to be redirected into domestic priorities, such as the health service, is perfectly reasonable, just as it is true, in theory, to say that outside the EU Britain could negotiate a free-trade deal with the U.S., even if it never does.

All of this nevertheless ignores the bigger argument—the real argument—that any “savings” pale in comparison to the wider economic impact of leaving the EU, rather like a worker who “saves” the cost of commuting by quitting their job to get a lower-paying one closer to home. There is little point in arguing over exactly how much they will save on bus fare—the point is their general welfare.

Here is where politics kicks in. Whether Britain really will be worse off out of the EU in the long term is not a question of fact, but of opinion and forecast, and therefore it’s open to disagreement and unfalsifiable value judgment. What if the worker is better off generally by not commuting to work, even if they are poorer? The same is true of Brexit: Most economists are sure Britain will not be as prosperous outside the EU as it would have been if it had stayed in, but that does not make leaving an illegitimate decision.

In the Cornell professor Max Black’s essay “The Prevalence of Humbug,” he describes the problem of “deceptive misrepresentation, short of lying,” especially through the use of “pretentious word or deed.” This seems a more apt label for Johnson’s account of his trip to Australia, and indeed many of his mistruths, but even this is not an adequate description of the prime minister.

[Read: Boris Johnson can remake Britain like few before him]

Might a better argument be that Johnson is not so much a liar, but rather what the Princeton professor Harry Frankfurt calls a “bullshitter”?

“The essence of bullshit is not that it is false but that it is phony,” Frankfurt writes in his seminal essay on the subject. Where it differs from the simple lie is in its intent. “The bullshitter may not deceive us, or even intend to do so, either about the facts or about what he takes the facts to be,” Frankfurt writes. “What he does necessarily attempt to deceive us about is his enterprise.” Whereas the liar has a relationship with the truth, the bullshitter stands apart, disconnected—an embodiment of postmodernism’s conceit that there is no truth, only contingent, subjective experiences.

To Johnson’s critics, of course, he is the bullshitter par excellence. Some insist that he was never really a euroskeptic journalist, or that he never really believed in Brexit but was happy playing the part because it brought him fame, notoriety, and power. When it comes to taxes or any manifesto commitments, does Johnson really care about them or is he prepared to say anything to win an election? This, ultimately, is a subjective judgment. It cannot be fact-checked.

Indeed, if making promises that cannot be delivered or saying half-truths to win elections is to be the criteria on which politicians are judged, then God help Western democracy. Johnson’s fiercest critics might want to pause before going too far down this track—Britain alone is littered with examples of senior politicians who have backtracked on commitments or could be accused of hypocrisy: Former Prime Minister John Major promised to clean up sleaze in politics despite having conducted an affair with a colleague just a few years earlier; his successor Tony Blair promised not to raise tuition fees on higher education, only to do so; Nick Clegg, a former deputy prime minister, later made the same promise, and even more egregiously broke it. The anti-Brexit Remain campaign itself looks far from perfect, having claimed that the British economy would contract by 3.6 percent and half a million people would lose their jobs if the country simply voted to leave. In the event, the economy grew, as did employment. Was this, then, a lie? It was certainly an incorrect forecast. But was it sincerely made? That is ultimately a question of judgment and trust. Even when it comes to Johnson’s Australian embellishment, is he any different from his peers? I spoke with one academic who rolled their eyes at the number of former politicians who claim to “teach at Harvard” when they, too, are just visiting fellows, like Johnson was.

The problem—as ever with Johnson—is that the reality is more complicated and subtle than whether he is a liar or not, sincere or fraudulent. One of Johnson’s long-term political rivals told me that the prime minister was basically a moderate conservative, but had been seduced by Brexit, which he had never previously argued for, “through a combination of ambition and romantic patriotism.” I think this is right—particularly the notion that Johnson has had a combination of motivations.

Anyone who has studied Johnson or knows him well understands that he is intensely focused, but has successfully eluded, through a persona of carefree liberation, the usual stigma attached in Britain to the overly ambitious. To say this makes him entirely fraudulent misses the point and, paradoxically, gives him too much credit.

Indeed, if Johnson is a bullshitter, he is not a good one: Voters seem pretty clued in to his intent. If anything, his entire public life seems to have been one long nod and wink with the public.

Take Johnson’s speech to the United Nations last week in which, ostensibly addressing the perils of climate change, he spoke of the belief that people still cling to that “the world was made for our gratification and pleasure” and that whatever mess we make, someone else will always clean it up. To British ears, it seems obvious that he is obliquely talking about himself, leaving those of us who cover him for a living trying to work out whether he does this on purpose as part of a game, whether he doesn’t know he is doing it, or whether he simply doesn’t care.

Johnson’s skill, it seems to me, resides almost as much in inviting the public into the game as it does in hiding his goals. In a sense, Johnson’s popularity is based on mocking everyone else’s bullshit, rather than duping people about his own ambition.

Take one telling moment in Johnson’s rise. In 2019, Theresa May was finally forced to resign as prime minister, paving the way for Johnson to realize his lifelong dream. Amid whirling expectation that he would soon announce his candidacy, he was asked whether he wanted the job. “I think … ahm … look … erm … ahm …” he mumbled, before adding: “I’m going to go for it. Of course I’m going to go for it.”

It was the of course that won the audience over. Johnson didn’t offer a declaration about a higher calling or feeling a duty to serve. He just said “of course.”

Johnson’s trip to Australia, as recounted 30 years on, is almost perfectly Johnsonian in its humor, jocularity, mild chaos, and sense of disappointment.

“What struck us more than anything else, apart from his youth at the time, was his affability,” Nelson, the French professor at Monash, told me over the phone from his home in Melbourne. “He was affable of the highest order you could say.”

Those who interacted with him, Nelson recalled, enjoyed his company, finding him entertaining, bright, and agile, but no great intellect. They were also struck by what was described as “a somewhat cavalier approach.” He arrived late for events and appeared to regurgitate his Daily Telegraph column rather than coming up with original remarks, yet was nevertheless engaging.

The overall impression left on those who spent time with him was that he was “lightweight but charming,” Nelson said. What has struck all those who dealt with him then is how consistent he has been since. “He seems to have changed hardly at all,” Nelson told me. “So similar to the persona we saw.”

Here we glimpse the paradox at the heart of Johnson: the slipperiness and the consistency, the embellishment and the truth, the factual error and the sincerity of the act.

The more time you spend with Johnson, the more you understand that this projection of chaos is both real and performative. It is the combination that is interesting.

Johnson is ferociously focused on his own advancement, strikingly disciplined when he feels he must be (in election campaigns, for instance). And yet, at the same time, his private life, personal finances, and way of working really are chaotic, infuriating many colleagues and friends and ultimately undermining his desire to be a revolutionary leader.

He is both the most underrated and overrated politician I’ve come across: dismissed as unserious by many, even after he has outmaneuvered them. In Paris, he remains a figure of bemused disdain, despite spending the past six months quietly working with the U.S. and Australia to steal the “contract of the century” from France. At the same time, he is given too much credit for things for which he is only partially responsible, such as anti-establishment populism, euroskepticism, the great realignment of British politics—all of which were powerful forces independent of Johnson.

Was it a lie that he was once a visiting professor of European thought in Australia, then? With Johnson, it is often hard to tell where a white lie meets a light sandpapering, and what is essentially true versus what is a misleading narrative deployed for his benefit.

The truth of his visit to Australia seems to be that he spent a couple of weeks in Melbourne having a nice time—two weeks that were not particularly chaotic or notable. He went, he charmed, he mildly disappointed, and he left.

He was the same Boris Johnson that the world knows today, a man who is both authentic and hidden—and consistent in being so.