Migratory insects number in the trillions. They’re a major part of global ecosystems, helping to transport nutrients and pollen across continents – and often travelling thousands of kilometres in the process.

It had long been thought migrating insects largely go wherever the wind blows. But there’s mounting evidence they’re actually great navigators and can select favourable conditions to undertake their journeys.

One outstanding question for experts has been how they react to varying wind conditions while en route. In research published today in Science, we show one migratory insect species, the death’s-head hawkmoth, can maintain a perfectly straight flight path. These moths are able to adjust their trajectory to compensate for rough wind conditions.

Tiny transmitters

Much of our knowledge of insect migration comes from direct observations. These include observations made using radar, or studies of population processes, such as using genetic methods, or measuring ratios of isotopes in tissues (which can reveal insects’ food and water sources and provide information on where they come from).

How individual insects behave, and the paths they take, during migration has been relatively difficult to study, mostly due to their small size and the sheer number of them. But recent advances in tracking technology have helped produce transmitters small enough to be carried by larger insects.

These transmitters weigh less than a gram and can be attached to individual insects. This allows us to track them directly as they migrate and learn what this process involves.

Migratory moths

Our study focused on the death’s-head hawkmoth (Acherontia atropos), an enigmatic moth found in Europe and Africa. The species is well known for the unusual skull-like marking on its thorax. When disturbed, it also has the habit of squeaking and flashing its bright-yellow abdomen.

The moth feeds on honey it steals from honeybee hives, entering the hive and piercing the honeycomb with its stout proboscis (its feeding tube).

While we know this species occurs in Europe, little is understood about its migratory behaviour and where it spends the winter. Adult moths tend to appear in Europe during spring (May to June), and the next generation of adults sets out in autumn (August to October) – likely making its way to the Mediterranean or North Africa, and perhaps as far as south of the Sahara.

It’s thought the species is unable to spend winter north of the Alps, so its migration is probably driven by low temperature and resource availability.

Tracking in the dark

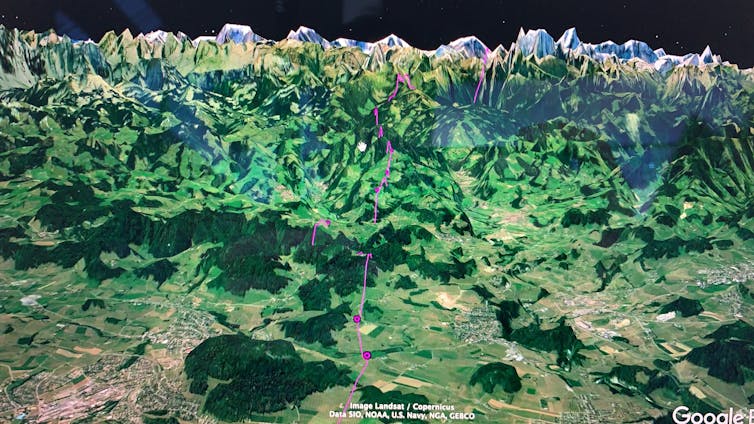

For our research, we tracked 14 moths for up to four hours each – a stretch of time long enough to be considered migratory flight.

We fitted each individual with a tiny radio transmitter, weighing less than 0.3g, before releasing them. A Cessna aeroplane with receiving antennas flew after them as they migrated, detecting their precise location every five to 15 minutes. This method gave us in-depth insight into their flight behaviour.

Radio tracking has successfully been used to investigate the migration of some day-flying insects, such as the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) and green darner dragonfly (Anax junius). However, it has never been used on nocturnal insects in the wild, or at this resolution.

In fact, our research marks the longest distance any insect has ever been continuously tracked in the field.

Making a bee-line

So what do moths do on migration? To our surprise, we found they flew along very straight paths, effectively making a bee-line for their destination. Some of the longest tracks reached nearly 90km over a period of four hours. This is a fascinating finding as such straight tracks are very uncommon in long-range migratory animals.

The moths also showed distinct strategies to deal with different wind conditions. When there were favourable tailwinds (winds going in the same direction as them) they flew downwind and were propelled towards their destination, or offset their heading slightly to maintain control of their trajectory.

In unfavourable conditions, such as headwinds (coming from the front) and crosswinds (from the side), the moths flew low to the ground and directly into the headwinds, adjusting their trajectory to avoid drifting off course. They also increased their speed to stay in control.

This remarkable ability to stay on course, even in unfavourable conditions, indicates the death’s-head hawkmoth has sophisticated compass mechanisms.

Where to next?

We’ve shown insects are capable of being expert navigators, on par with birds, and aren’t at the whim of the winds as we once thought. This is an important discovery in migration science.

That said, there’s still a huge amount we don’t know about how insects migrate and where they go. The next step will be to understand exactly what mechanisms these moths use to stay on their path. For instance, are they following the Earth’s magnetic field? Or perhaps relying heavily on visual cues?

The more we understand, the closer we can get to being able to predict the phenomena of insect migration. And this would have broad implications – from managing threatened species and species with agricultural benefits, to having better control over agricultural pests.

Myles Menz received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 795568. He is affiliated with the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behaviour, Germany.

Martin Wikelski does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.