Water levels on the Rhine River are set to fall perilously close to the point at which it would effectively close, putting the trade of huge quantities of goods at risk as the continent seeks to stave off an economic crisis.

The river at Kaub, Germany -- a key waypoint for the shipment of commodities -- is set to drop to 47 centimeters (18.5 inches) by the weekend. That would take it to within 7 centimeters of being all but impassable.

Europe is already facing its worst energy-supply crunch in decades as Russia chokes off natural gas, stoking inflation. Now climate change is adding to the continent’s woes. An impassable river could halt the flow of everything from fuel to chemicals as governments try to prevent the energy crisis from tipping the region into recession.

“Coal shipments are already restricted by low water levels because fewer ships are available, and the ones that are ready to use carry less cargo,” energy supplier EnBW AG said in a statement. “Shipment costs for coal are therefore increasing, which in turn inflates the costs of operating coal plants.”

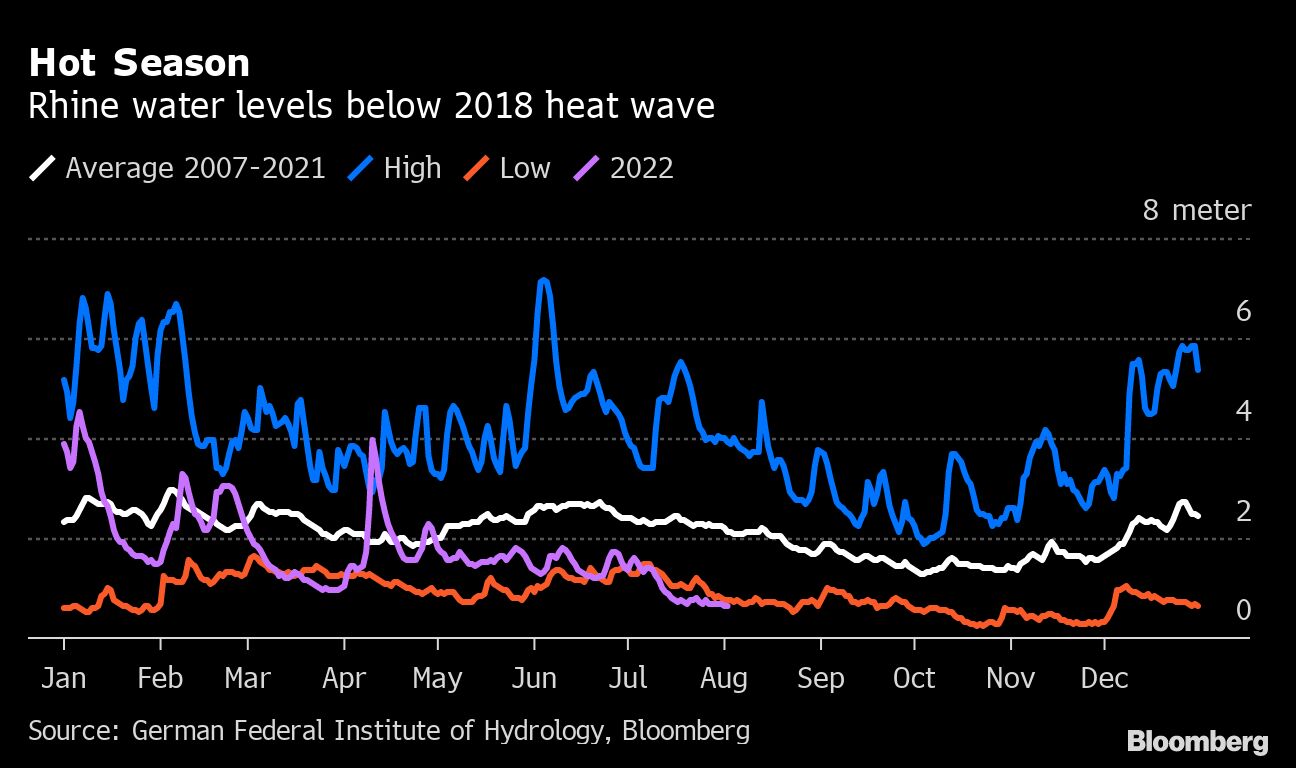

Back in 2018, the last time the water got lower, the disruption dented Germany’s fourth-quarter growth by 0.4%, analysts at JPMorgan estimated. This time around, the need for the waterway may well be even more acute because it’s one means of compensating for lost Russian energy supplies.

Snaking roughly 800 miles (1,288-kilometers) from Switzerland to the North Sea, the Rhine is vital for deliveries and exports of heating oil, gasoline, coal and other commodities. Low water means barges have to reduce their loads to navigate the river.

The need for coal has risen because Germany is getting less gas from Russia as Moscow pressures the West to ease up on sanctions. Germany is at risk of losing 4.8% of economic output if Russia shuts down supplies of natural gas to the country, the International Monetary Fund warned last month.

On Tuesday, the water level at Kaub fell to its lowest since 2018, a year that saw widespread disruption for key industrial users. It’s now a little over 60 centimeters and is forecast to drop to 47 centimeters on Saturday, according to the German Federal Waterways and Shipping Administration.

The measured water level is not the actual depth of the river. At Kaub, for instance, when the measured level was close to 90 centimeters a few weeks ago, the actual depth of the river was about two meters.

Commodity Barges

A representative for Germany’s Federal Institute of Hydrology said in July that it becomes uneconomical for barges carrying commodities to sail past Kaub when the measured level drops to 40 centimeters or below.

The low levels are already disrupting trade flows, limiting how much fuel barges can carry into inland Europe. Switzerland, which uses the Rhine to import oil-based fuel, is releasing stock from its strategic reserves. Parts of inland Europe’s fuel supply are also being hampered by refinery outages in Germany, the Czech Republic and Austria.

“With the Rhine transport disrupted and alternatives such as rail and road looking increasingly expensive, it will be difficult for Germany and Switzerland to build gasoil/diesel stocks before temperatures cool,” said Josh Folds, a European oil analyst at consultants Facts Global Energy.

Falling River Rhine Adds to German Economic Woes: Supply Lines

Shipping costs are already out of control. It now costs more than 200 euros ($204) a ton to transport some fuel to Basel in Switzerland. That’s the highest in at least three years and compares with 25 euros a few months ago.

When barges can’t load full, more of them are needed to transport the same amount of cargo.

The low water is impacting the shipment downriver of some components used to make gasoline for blending, according to Joseph McDonnell, an oil products analyst at Energy Aspects. The flow of petrochemical feedstocks, like naphtha, from the Amsterdam-Rotterdam-Antwerp hub to inland facilities, is also being affected, he said.

Company Preparations

Companies have been taking steps to prepare. EnBW has been building up its coal stock. Chemical manufacturer BASF SE is chartering special barges for low water. Evonik Industries AG said it has chartered additional ships and trucks to compensate for lower cargo levels on barges.

“Currently, there are no significant constraints to our supply chains and we feel like companies are better prepared today than they were in 2018,” Evonik said in a statement.

Still, manufacturers that seek to shift transportation from the Rhine to roads or railways could find themselves out of luck. VTG AG and Hoyer Group -- two specialty logistics companies that move chemicals, gases, coal and petroleum products -- said their trucks and railway cars are already operating at full capacity due to staff shortages and handling issues in railway transport where turnaround times have recently been delayed.

Demand for coal transportation is also at a record high since Russia invaded Ukraine, when industries started to compensate for gas supply shortages by readopting coal, said Rene Abel, head of corporate communications at VTG.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.