The mist hung heavy on the Kinabatangan River on the July morning I looked for helmeted hornbills, one of the most elusive and endangered birds in the world. Everything was wet from days of afternoon thunderstorms and late-night drizzles. The air smelled green and fresh, but with an underlying note of decay. The river, swollen by the unseasonably heavy rains, flowed swiftly and quietly.

In any other year, the Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary in Sabah, the Malaysian state on the northern tip of Borneo, would be abuzz with birdwatchers and backpackers. But Malaysia had closed its borders due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and I was one of four guests at the only lodge near the sanctuary still open for business.

The sanctuary’s animals seemed to be enjoying the lull. During the past two days, I’d seen 15 elephants feeding and bathing by the river; three orangutans—one pregnant and one with a baby—sitting in a fig tree; scores of proboscis monkeys, showing their bulbous noses and red erect penises; and flocks of black hornbills, wrinkled hornbills, and bushy-crested hornbills. I’d been lucky, but so far not lucky enough to see a helmeted hornbill glide through the forest with its massive wings extended like a living dinosaur’s.

My guides led me along a narrow trail uphill through the forest. We stepped into muddy puddles—made by wild boars the night before—and squeezed between rocks, taking care to avoid the gaping holes that plunged into dark underground limestone caves. When we paused in a small clearing on a rocky hill, we were swarmed by mosquitoes.

Helson Hassan, one of my guides and a hornbill conservationist, pointed to a huge meranti tree. High on the thick trunk, more than a hundred feet from the ground, was a hole about the size of a basketball—a prized secret, and a source of hope, for Helson and his colleagues.

Helson’s team, led by the researcher Ravinder Kaur, studies hornbills and their nesting activities in the Kinabatangan sanctuary. During his daily rounds, Helson might scan the skies from a boat on the river; follow hornbill males as they carry figs and insects back to their nests; and check the ground for hornbill feces, a sign of birds nesting above. Encounters with crocodiles, elephants, and wasps are occasional but inevitable hazards.

Hornbills must nest in cavities, and for five of the past seven years, the same pair of helmeted hornbills has nested in the hole in the meranti tree, producing a chick each year. Five chicks over seven years might sound like a small number, but considering the precarious state of the species, it’s significant. For the past two months, Helson had been watching the hole closely, hoping that it would once again house a family of helmeted hornbills.

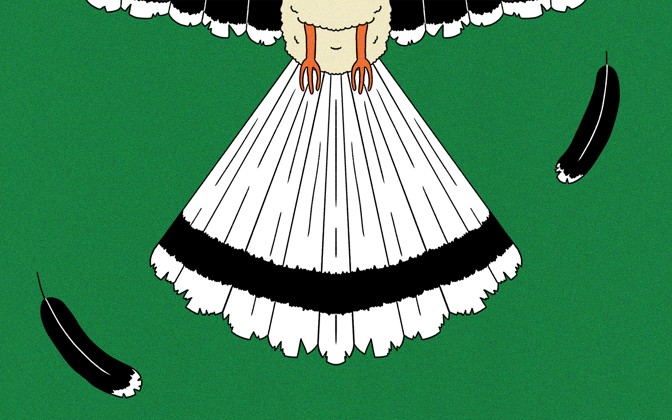

Helmeted hornbills are enormous birds—measuring almost six feet from beak to tail—and they live in some of the world’s oldest forests, ranging from southern Thailand to the islands of Sumatra and Borneo. They feed mainly on figs, and because they forage over great distances, they disperse the seeds far and wide, planting trees that feed many forest animals.

While many of the other 30 species of Asian hornbills are distinguished by bright-yellow, orange, or white head feathers and beaks, the helmeted hornbill is less showy, with a bare, wrinkled neck pouch, a spray of rust-brown head feathers, and a straight yellow beak. But the species is immediately recognizable by its maroon-colored “helmet,” or casque—a brick-shaped growth of keratin at the base of its beak that covers its brow and the crest of its head.

The hornbills of Southeast Asia face multiple threats to their survival. Logging and development have decimated the forests they live in: Between 1990 and 2010, the region lost 79 million acres of forest, an area around the size of New Mexico. While some smaller hornbill species can survive in semi-urban or fragmented forests, helmeted hornbills and other large species need vast, contiguous forests with tall, thick-trunked nesting trees.

[Read: The birdsong that took over North America]

Many hornbills are targeted by poachers, but helmeted hornbills are especially vulnerable because of their uniquely large and solid casques. For centuries, the casques have been carved by artisans into elaborate trinkets and ornaments; in the 14th century, Southeast Asian kingdoms paid tribute to the Chinese emperor with gifts of hornbill casques. In 1975, the international trade in helmeted hornbills was outlawed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, but sales continued on the black market.

In late 2012, an Indonesian hornbill conservationist named Yoki Hadiprakarsa received a photo, from a friend, showing stacks of helmeted hornbill heads for sale at an Indonesian village market. Yoki had long suspected that the species was in serious danger, but no one had documented the extent of the poaching—or even the number of surviving helmeted hornbills. After surveying villages and interviewing wildlife traders in West Kalimantan, an Indonesian province on Borneo, he estimated that poachers were killing about 500 helmeted hornbills every month in West Kalimantan alone. Most of the hornbill parts were sold to China.

After 2013, Yoki asked villagers in Sumatra and Borneo if they had seen the bird or heard its distinctive laughter-like call. “Even though they spend one week in the forest, [they] would be very damn lucky to hear just one,” he told me. “In fact, in some areas, they don’t hear it anymore.”

Yoki’s findings shocked the conservation community, and in 2015 the helmeted hornbill was designated as “critically endangered,” just one rung away from “extinct in the wild” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. But experts still don’t know how many helmeted hornbills are left in the forests.

“There is no one single magic number,” says Chin-Aik Yeap, senior conservation officer at the Malaysian Nature Society and a member of the IUCN Helmeted Hornbill Working Group. While land animals like tigers can be surveyed with camera traps, surveying birds requires a lot of hiking through forests to see or hear them, Yeap told me, and given the remote, thickly forested terrain preferred by helmeted hornbills, “obtaining even the most basic of estimates from the field is—to put it in a simple word—hell.”

Still, if Yoki’s findings in West Kalimantan represented poaching rates throughout the species’ range, helmeted hornbills were clearly running out of time. In 2018, the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Hornbill Specialist Group announced a 10-year conservation action plan for helmeted hornbills, outlining actions needed to protect hornbill habitat and eliminate illegal trade. The same year, the Indonesian government approved a conservation plan for helmeted hornbills; Thailand is now developing its own national plan.

Since then, agencies and NGOs across Southeast Asia have stepped up their scrutiny of the hornbill trade, tracking online sales and intercepting shipments of hornbill parts. NGOs in Indonesia are also hiring local residents as rangers, training them to watch for and report hornbill poachers in their forests. While the number of hornbill products available online appears to be declining, experts say, enforcement might have simply driven poachers and traders deeper underground. Anuj Jain, bird-trade coordinator at BirdLife International, a global partnership of bird-conservation groups, told me the state of hornbill poaching “is a big unknown at the moment.” What is certain is that it is still happening: On November 3, Indonesian law enforcement confiscated 71 helmeted casques from two men in Sumatra.

For many years, another big unknown was the basic ecology of helmeted hornbills—where they live, how often they reproduce, and what they need to survive. As late as 2015, only a few short-term studies had documented the birds’ natural history. Ravinder Kaur and her team in the Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary were—and still are—among a tiny handful of researchers paying close and sustained attention to helmeted hornbills.

Ravinder, who is 38, once disliked conservation biology. She applied to study veterinary science at university, but was instead offered a place in a conservation-biology program—her last choice. “I liked dogs and cats, not wildlife,” she told me. During her first year, upset about losing her dream career, Ravinder sat at the back of the class and was so miserable she lost weight. But when she took a class trip to the rain forests of Danum Valley in Sabah, she experienced the joys of studying wildlife: sleeping under starry skies and giant trees, following elephant trails, and listening to orangutans swing through the canopy. After graduation, she was hired by the Malaysian Nature Society, where she worked to conserve endemic butterflies and plants. When it came time for her to choose a new project, the leader of the society’s hornbill program invited her on a field trip, and Ravinder was intrigued by the unusual birds. “I didn’t pick hornbills,” she said. “They picked me.”

In 2012, while pursuing her Ph.D. at the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur, Ravinder began to collaborate with HUTAN, a conservation NGO in the Kinabatangan region, on hornbill research. HUTAN, which means “forest” in Malay, was founded by primatologists, and its researchers have been studying orangutans in the Kinabatangan sanctuary since the late 1990s; they began studying elephants in 2000. Ravinder helped expand the organization’s work to hornbills, and she launched a separate group, called Gaia, dedicated to hornbill conservation.

The Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary, which straddles the floodplain of the 350-mile-long Kinabatangan River, is home to a wide array of wildlife: Bornean pygmy elephants, orangutans, crocodiles, and eight species of Asian hornbills, six of which are threatened. Before the pandemic, thousands of tourists, mostly European, filled the riverboats that regularly cruise through the sanctuary, hoping to catch a glimpse of its wild residents.

Yet the Kinabatangan sanctuary is not the thick rain forest one might expect. The Sabah state government established the sanctuary in 2005, after most of the area’s forest had been selectively logged; the sanctuary is fragmented and surrounded by oil-palm estates, farms, and villages. Most of the older hardwood trees have been cut down, and with them many of the larger, higher tree cavities that form when heart-rot fungi attack the center of a tree trunk. And without cavities, the Kinabatangan sanctuary can’t provide much sanctuary to hornbills.

Primary forests have supported cavity-nesting birds for a very long time, Kristina Cockle, an ornithologist at the Institute of Subtropical Biology in Argentina, told me. But when big trees are removed, the slow-moving heart-rot fungi can’t form as many large tree cavities. In a four-year study of forest plots in Argentina, Cockle found 17 bird cavity nests in unlogged forests but only one in logged forests. (While her findings suggest that few cavity-nesting birds are able to breed in logged forests, further studies are needed to determine if the birds’ breeding was limited by cavities or some other factor.)

In 2017, as part of her doctoral research, Ravinder and her team surveyed the tree cavities within a 2,500-acre section of the sanctuary. By walking through the forest and scanning the trees with binoculars, they found just 19 cavities, most too low to the ground to be used by helmeted hornbills. All of the cavities remained unoccupied during the hornbill breeding season.

While the helmeted hornbill population in the sanctuary was better protected than most, Ravinder and her colleagues knew that it needed more nesting cavities to survive. They also knew that they couldn’t wait for the sanctuary’s trees to grow larger, and for heart-rot fungi to slowly invade their trunks. They needed a more immediate solution.

In some places, artificial nest boxes have successfully boosted hornbill numbers. In Budo–Su-ngai Padi National Park in southern Thailand, the Hornbill Research Foundation has installed 22 boxes, and over the past 16 years, 55 hornbill chicks have fledged from them. But the park’s helmeted hornbills have shown no interest in the boxes. In fact, helmeted hornbills have so far rejected every nest box tried in Thailand and Malaysia.

The first nest boxes for hornbills in the Kinabatangan sanctuary went up in 2013. HUTAN collaborated with European zoos to build and install five nest boxes in the forest. But HUTAN was busy with the demands of conserving elephants and orangutans and did not monitor the hornbill boxes. When Ravinder arrived at the sanctuary, she installed data loggers at the nest boxes and in several natural cavities used by oriental pied hornbills. She found that the temperature and humidity within the nest boxes, which were made of plastic and encased in Styrofoam and cement, were more than twice as variable as those within the natural cavities.

The nest boxes had failed to replicate the stable and cool environments of the natural cavities, and while a few hornbill species visited them, only a single pair of oriental pied hornbills stayed to build a nest. After the 2016 hornbill breeding season, the empty boxes looked like “epic failures,” Ravinder said. “We were ready to take them down.”

Then, in mid-2017, a pair of rhinoceros hornbills nested in a box right by the river, eventually fledging one chick. Rhinoceros hornbills are almost as picky about their nest sites as their helmeted cousins, and the chick was the world’s first rhinoceros hornbill to fledge from an artificial nest box outside of captivity. “That one was like, ‘Woo-hoo!’” Ravinder recalled.

In 2018 and 2019 the rhinoceros hornbill pair returned to the same box, and a second pair nested in another box. As they typically do in tree cavities, the females sealed themselves and their eggs inside the boxes, narrowing the entrances with soil and feces. The males, left to forage, fed their families through a slit in the clay barrier. After at least three months, the females and their fledged chicks broke their seals and emerged.

In 2019, near the end of the rhinoceros hornbill breeding season, Ravinder and her husband, Sanjitpaal Singh, a professional photographer, waited on a boat on the river in hopes of seeing a fledgling emerge from one of the boxes. After days of waiting, they saw a yellow beak poke out of the slit, followed by a black head and one shoulder. The next moment, the fledgling was out of the box—and then falling, landing on a shrub near the water.

As the parents flew down to their fledgling, which was perched unsteadily with its feet wide apart, Ravinder and Sanjitpaal watched in horrified suspense. “The whole family was threatened now, so close to the ground” and vulnerable to predators, Ravinder recalled. One wrong move by the fledgling and it might drown in the river. Fortunately, the fledgling eventually managed to make its way back up the tree, flying in short hops from branch to branch.

To date, five rhinoceros hornbill chicks have fledged from the nest boxes. While the progress is thrilling, Ravinder’s team can’t tell why those particular nest boxes appealed to the birds. “We are still scratching our heads,” she said.

In 2017, before the nest boxes succeeded in attracting the rhinoceros hornbills, Ravinder began to think about new box designs. When she told Helson about the fluctuating temperature and humidity inside the boxes, he offered to design what they came to call the “phase two” boxes. After all, he had built boats and houses—nest boxes seemed easy. Over three weeks, he made two prototypes out of wood, fiberglass, and new insulating materials inspired by his childhood experiences building boats with his father. When he told his young children that he was building houses for birds, they concluded that he was a superhero who rescued birds.

The phase-two design kept temperature and humidity fluctuations inside the box to a narrow band, maintaining conditions close to those of the natural cavities. Gaia and HUTAN have since installed 18 of the new boxes in the forest, but while various hornbill species have visited the boxes, none has nested in them. Ravinder and Helson speculate that the birds might be avoiding the lingering smell of epoxy, or might be put off by the lack of moss and lichen on the walls. “We are learning,” Helson said.

As much as Ravinder would like to continue improving and introducing nest boxes, each one costs hundreds of dollars and requires hundreds of hours to make and install. The alternative, at least for the smaller hornbills, is to make existing tree cavities more appealing by correcting their ceilings or floors or the size of their entries. Improving an existing cavity is cheaper and faster than installing a nest box—as long as you have basic carpentry skills and the courage to climb into the tree canopy.

From 2016 to 2018, the Gaia and HUTAN teams improved six natural cavities, dangling high above the forest floor as they chiseled the interiors and entries to suit the hornbills. They even attached ferns to one cavity for shade. Their efforts were rewarded: Oriental pied hornbills have nested in four of the repaired cavities and produced at least nine fledglings.

While nest boxes and cavity repairs can help hornbills, they are imperfect, short-term solutions. Un-logged forests with enough tree cavities would not even require nest boxes, the researchers Yeap and Yoki told me. The long-term solution is to protect old-growth forests—not only from logging, but also from the humans who continue to hunt helmeted hornbills.

Back on the hill in the Kinabatangan sanctuary, Helson and I waited for signs of a helmeted hornbill. I stared up at the tree trunk, whose cavity had housed at least five helmeted hornbill fledglings in the past. Helson warned me not to get my hopes up; neither he nor his colleagues had seen this particular hornbill pair in months.

Helson vividly remembers a day in November 2019 when he, Ravinder, and Sanjitpaal were observing the nest. The female had emerged from the cavity five weeks before, but had gone missing. The chick was still in the nest, fed by the male alone. The team sensed that things were amiss; though the sanctuary is closed to unauthorized visitors, they had recently smelled cigarette smoke along the trail in the early morning.

Suddenly, a twig snapped. Ravinder looked toward the sound and saw a stout man walking up a nearby rocky hill, carrying a long bamboo pole. Sanjitpaal yanked Ravinder to the ground and motioned for Helson to hide. But the man saw them; he turned around and waved a warning at someone behind him.

Minutes passed as Ravinder and her team debated what to do. They had no idea how many people there were, or what they wanted. Then they heard a gunshot, possibly two. They scrambled back to the river and later lodged a police report. When they returned to the hill a few days later—their numbers reinforced with a few HUTAN staff—they saw a man standing at the base of the helmeted hornbill tree, holding a machete. Hours later, police arrived and searched the forest, but no intruders were found.

Hornbill poaching hasn’t been a concern in the sanctuary, and Ravinder suspects that the intruders were poaching swiftlet nests from a cave in the forest (the nests, made of hardened saliva, fetch high prices as a gourmet delicacy). But any one of the intruders could have seen the helmeted hornbills and taken the opportunity to kill the female. “It was very emotional for us, because we have been watching this nest,” Ravinder told me. “Whatever happened to them, we felt it too.”

The male helmeted hornbill finished his parenting duties alone. In December, the fledgling broke out of the cavity and flew off with its father. By then, Ravinder and Sanjitpaal had left Kinabatangan for their home base in Kuala Lumpur, and only Helson and Amidi Majinun, another Gaia research assistant, saw the fledgling.

Since then, nobody on the Gaia team had seen the helmeted hornbill pair or their fledgling, and during our visit in July, Helson wasn’t optimistic; after 20 minutes of watching, he seemed ready to leave.

Suddenly, he pointed into the forest and motioned for me to listen. “Hoo … hoo … hoo …” A series of solid, rounded calls rang in the distance. Could it be?

“That’s a helmeted hornbill,” he said, smiling. “Wait for it.”

“Hoo … hoo … hoo-hoo …” The calls quickened, the notes smashing together before bursting into a rapid “Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha-ha!”

Helson patted my back. “Good job, bro. You didn’t see a helmeted hornbill, but good enough to hear it,” he said. I left reluctantly, still hoping to see an enormous bird sail among the trees.

This has been an “eerily quiet” year for all of the hornbills in her study area, Ravinder told me. The birds used only one of the 13 identified natural cavities, and none of the nest boxes. Perhaps the hornbills have moved on to feed in other forests, or have forgone nesting because of the unusually heavy rains. Nobody knows.

“I like to keep positive and think that maybe in a couple of years’ time we’ll see them coming back, and we find out that maybe this is just a pattern that happens,” Ravinder said.

A week after I left Kinabatangan, Helson sent me a photo he took near the vacant helmeted hornbill cavity. Three birds were perched on a leafless branch: two oriental pied hornbills, and one adult male helmeted hornbill.