A year and a half into the pandemic, millions of Texans have been infected with the coronavirus and more than 57,000 have died. Vaccines brought family reunions and the hopeful, albeit short-lived, promise of a semi-normal summer. But with less than half of Texas’ population fully vaccinated, the more contagious Delta variant of the virus took hold and confirmed cases and hospitalizations surged in July and August. When this pandemic ends, it will leave behind scars far beyond what is captured in those numbers: jobs lost; homes lost; relationships, people, places, ways of life lost.

For more than a year, we’ve been following a group of Texans from across the state, chronicling the ways the pandemic has altered their lives in overlapping yet infinitely different ways. The first part of this series was published last September and the second, this March. In this third installment, we hear from these folks as they cautiously navigate their way into this next uncertain chapter. These are ordinary people dealing with extraordinary circumstances. We’re grateful to them for sharing their stories.

James T. Campbell

Age: 65

Profession: Insurance executive

Location: Houston, Harris County

Almost a year and a half after James T. Campbell lost his dad, James Cleophas Campbell, to COVID-19 in March 2020, he still avoids his father’s bedroom. His mother, Rosa Campbell, still sleeps in the guest room, leaving their bedroom just as it was when an ambulance took her husband away in the early days of the pandemic. “I haven’t even gone in the room,” James T. says. “She asked me if I want my dad’s boots or his jewelry or anything like that, and I’m not yet prepared to do that.”

James T. thinks about his father nearly every day. His phone screensaver displays a photo of the pair at a Houston Texans game, “so every time I open up my phone, I see him.” He senses their close connection most strongly at night. Like his father, James T. suffers from insomnia, often obsessing over family problems. Lately, he’s spent many nights awake worrying about his 86-year-old mother, who refuses to get a COVID-19 vaccine. James T. and his sisters have spent months trying to change her mind but have begun to think that she may never do so.

A retired nurse, Rosa has continued to isolate instead of getting the shot, in part because she once suffered a severe reaction to the flu vaccine. She spends most of her time at the family’s three-bedroom house in the Houston neighborhood of Pleasantville. Others run her errands, everyone dons masks around her, and she attends church and funerals via Zoom.

In recent months, Campbell family gatherings have resumed without the patriarch and with many precautions. Mother’s and Father’s Days used to see the homestead jampacked with relatives. This year, a small family circle gathered for Mother’s Day, and only vaccinated visitors were welcome inside. Everyone wore masks and brought plates of food. James T. made BBQ chicken breasts, smoked over mesquite on the backyard grill the way his mother likes them. Yet with Rosa and many children in the family still unvaccinated, he has not moved ahead with plans for a large memorial for his father.

On Father’s Day, James T. made his fourth pilgrimage to Houston National Cemetery. “James Cleophas Campbell, a World War II veteran, born August 17, 1931, and died March 31, 2020,” is etched on the gravestone. On other visits, James T. had felt overcome by grief, haunted by what-ifs. What if Donald Trump had taken the coronavirus seriously and told people to wear masks earlier, especially around elderly relatives? What if James T. and his family had known in early 2020 of the risk of bringing COVID-19 home? Maybe his father would still be alive.

This time, he glanced across the rows of white stones and noticed others who were honoring their fathers, too. Most had passed away long before the pandemic, yet “I felt a kinship with all of those people out there,” he says. “There was just kind of a serenity in it.” He knows he’s also joined a far larger circle of grief: Millions of people mourn the more than 648,000 lives lost to COVID-19 in the United States.

He slipped a bouquet of flowers into a vase on the grave and spoke to his dad: “I miss you. I love you. I’m trying to uphold what you wanted to be done. I can never be you, but I’m always going to try.” —Lise Olsen

Lauren Byrd-Moreno

Age: 29

Profession: Student

Location: Beaumont, Jefferson County

Lauren Byrd-Moreno is looking forward to the day that she’s no longer in a long-distance relationship with her husband, Chris Crain. He was finally released from prison on parole this summer, but for now, he’s living at a halfway house. Byrd-Moreno isn’t counting on having him home for good until November. But she was so used to bad news when she checked his parole status, it was a welcome relief to finally have an end in sight. She didn’t see Crain, who was incarcerated in the Clemens Unit in Brazoria County, for about a year because of COVID-19 restrictions. “I was terrified for us,” she says. “I didn’t know if I was going to get a phone call saying that he’d passed away.”

Seeing what she says was the worst of the prison system during the pandemic inspired her to change her college major to criminal justice this spring. “I went through these classes and I realized, a lot of this, I’m already familiar with,” she says. Since early last year, she’s found herself thrown into advocacy work as her husband and thousands of others in the Texas prison system have been at high risk of contracting COVID-19. Many inmates were given harsh sentences for low-level crimes or otherwise kept in jail when they could have been released with better parole programs and support, she says; instead, they died from COVID-19 behind bars. Now she wants to work on changing the way rehabilitation programs function and diverting people from prison. “I want to help people get out sooner and go home a little better than they came in.”

Byrd-Moreno is planning to take a break from classes this fall. Her hands are full with parenting, moving, and cobbling together gig work to pay the bills, and when Crain comes home, she knows she’ll be even busier helping him adjust. She moved out of her grandmother’s house and into her own apartment this summer so the family can have more space for themselves. And she left her job waitressing at an IHOP in Beaumont this spring, tired of the cycle of co-workers testing positive for the coronavirus and the restaurant shutting down temporarily, cutting into her pay. She’s since taken on work through a food delivery app and is babysitting a former co-worker’s child. “It’s difficult because I don’t have a set income,” she says. “But I’m my own boss now.”

Byrd-Moreno is hoping to take some time for herself soon. “It’s a weird in-between phase, where I’m still trying to maintain my adult life and take a break at the same time,” she says. It’s been a tough year and a half, and she knows she and her family aren’t at the finish line yet. She says her schedule has been so unpredictable that as of this summer, she still hadn’t set aside time to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Crain wasn’t vaccinated in prison, and her kids, all under age 12, are too young. As the Delta variant spreads quickly, sending many young, unvaccinated people to the hospital, she also feels a lingering fear that schools might have to shut down again when they go back in person this fall.

“It’s kind of nerve-wracking,” she says. “But we’re definitely more hopeful.” —Amal Ahmed

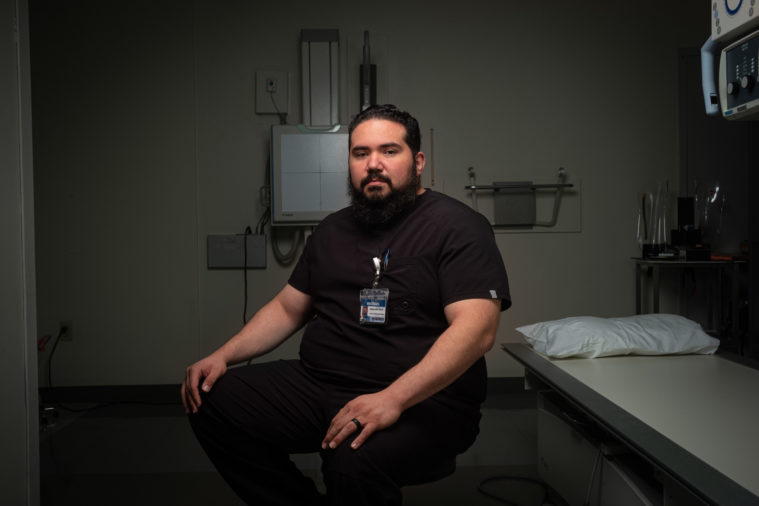

Michael Saenz

Age: 36

Profession: Radiologic technologist

Location: Mount Pleasant, Titus County

This spring marked a new kind of anniversary for Michael Saenz: one year since he barely survived COVID-19. In mid-June 2020, he was released from the hospital after a monthlong battle with the disease and more than a week on a ventilator. His wife “got more emotional than I did,” Saenz says of the one-year mark since he recovered—just in time to spend Father’s Day with their son, who was born days after the coronavirus was first confirmed in Texas. “But then again, they’re the ones that went through more of the emotional part of it, you know. Going through whether or not I was coming out of the hospital, or what the next day would bring.”

Saenz and his wife are expecting their second child, due in September. Their son, now almost a year and a half, is “growing, he’s walking, he’s throwing tantrums,” Saenz says with a laugh. “He’s a healthy boy.” As for Saenz, he’s been mostly feeling well, though he says working out, which he’d gotten back into as he started feeling back to normal last summer, “went kind of down the drain,” a casualty of kids and life. But more than a year after he was sick, he’s still having lingering symptoms, including body aches and pains. In the past few months, Saenz, who lost his sense of smell and taste for weeks after he was sick, has started experiencing a “phantom smell.” Every so often, “I’ll get a kind of whiff of cigarette smoke,” he says. “But nobody is smoking around me.”

Since Saenz returned to work as a radiologic technician at Titus Regional Medical Center last summer, there have been several COVID-19 waves at the rural hospital. The last was in January and February of this year, but as of July, cases had started to tick up again. The vaccination rate in the Northeast Texas county lags far behind that of the state, with just over 1 in 4 residents fully vaccinated. As of this summer, much of the nursing staff still wasn’t vaccinated. The hospital partnered with community leaders and groups to try to boost vaccinations and offered walk-up shots at its clinic four days a week. Titus Regional, which had a long stretch without any COVID-19 patients, suddenly had 12 one day in July. Meanwhile, the ICU was full with non-coronavirus patients, in part because a hospital nearby that was short on staff was diverting patients there.

BECOME A MEMBER

Help make journalism like this happen.

Saenz got his COVID-19 vaccine at the hospital in late December. After likely catching the virus from a patient there last year, now “I feel like I’m more protected and not as vulnerable,” he says. But his family is still unvaccinated; his son is too young, and his wife is holding off while she’s pregnant. If he forgets his mask when he goes to a store, he’ll be more lenient now and go in without it; if his wife does, she’ll drive home to pick hers up. The family still tries to avoid big gatherings. They’ll pick up food and bring it home, or go out for a picnic. “We try to be more careful,” Saenz says. When he gets home, especially if he’s been in contact with COVID-19 patients, Saenz says he still tries to change before he hugs his wife or son. “I don’t want to transfer anything to them.”

Recently, as they were thinking about the year that had passed since Saenz was sick, his wife asked what he was most grateful for that week. His answer was simple: the week. “She wanted me to be more specific,” Saenz says. “I was like, ‘Well, I’m here. Last year I wasn’t.’ So, yeah, it was nice to be able to be here for a year. And hopefully many more.” —Sophie Novack

Victoria Randall

Age: 25

Profession: Logistics administrator

Location: College Station, Brazos County

Victoria Randall has spent much of the COVID-19 pandemic waiting. Waiting for the inevitable call from her boss telling her that she’d lost her job. Waiting for the state’s unemployment benefits to kick in. Waiting to hear back about job applications. Waiting for her mental health to improve, for bouts of intense pain to let up, for the new medications to start working. For the COVID-19 vaccine. Most of all, waiting to find a new normal.

Randall got her Johnson & Johnson shot in early March, but being vaccinated hasn’t changed things for her all that much. The jobs she’s had during most of the pandemic have required her to work in person. And while catching the coronavirus was always a concern, she’s had plenty of other pressing health issues to deal with. Randall has suffered from depression and anxiety for years and spent much of the past year and a half trying to find an equilibrium. She’s also been plagued by chronic pain for a while but was never sure why. In late May, her doctor diagnosed her with fibromyalgia, which can cause widespread pain and debilitating fatigue. “I wake up some days feeling like I’ve been wrapped in heavy chains,” Randall says.

She prides herself on pushing through the pain; unless it’s too unbearable to walk, she goes into work. But the illness “does not care if you are tough,” she says, and she’s still struggling with how to cope. She’s already burned through the six days of annual sick leave that her job—doing logistics for an internet hardware supplier—provides. And while her boss has been flexible and understanding, she doesn’t like “being up against the wall like that.”

Adding to her stress, her current job also pays much less than the one doing marketing for a restaurant chain that she lost last March. The life she had built in Dallas before the pandemic quickly unraveled; when she started living alone, running out of savings, her depression and anxiety deepened. She decided to break her apartment lease and move to College Station to live with a friend’s family.

The federal stimulus payments and unemployment benefits—once the state approved them—helped her stay afloat, and she’s slowly been able to rebuild her savings. But looming in the back of her mind is the $1,400 in unemployment benefits that the Texas Workforce Commission said she was overpaid while she was between jobs last year and has to return. She still hasn’t heard anything from the agency since she appealed the claim in December.

Randall wants to live alone in a one-bedroom apartment again. But her regular psychiatric and therapy appointments aren’t cheap. All told, she budgets nearly $500 a month for doctor visits and medications. That’s far more than she can afford on her current income. Maybe, she thinks, she could find an affordable apartment in Houston or San Antonio. But she’s wary of moving far and having to find new medical providers again, after finally finding ones she likes. So she wonders if a two- or three-hour commute back for her monthly appointments would be so bad.

For now, Randall isn’t thinking too far ahead. She scrolls past the stories about COVID-19 surging again as the Delta variant spreads—it’s too overwhelming. “I’m really just trying to get through today and the next day,” she says. “COVID ate a lot of my hopes and dreams.” There are the small triumphs: the deal she got on a set of new car tires, the haircut she got in June—her first in a year and a half—and the Angry Orchard hard cider she drank to celebrate her 25th birthday in July, “because the last year and a half have been hell.”

One thing Randall isn’t waiting for: to get back to the same place, the same person, she was in Dallas. “There isn’t a normal again. There’s only the new normal that we establish,” Randall says. “I’m never going to get the me from before back.” —Justin Miller

Erin Tolman

Age: 34

Profession: Teacher

Location: Arlington, Tarrant County

Church these days is different for Erin Tolman and her family. They’ve cautiously returned after more than a year away, since Tolman, her husband, and their 14-year-old daughter are now vaccinated against COVID-19. But Tolman spends much of her time there with her son in the church library, which she manages and which was closed for much of the past year and a half. She prefers it there; it’s quieter, without so many people around when services are going on. It’s been an adjustment in the months since being fully vaccinated, to be back in public, she says. “For me, it was even a struggle at first to go back to church and see all the people out. It took me time to adjust and get comfortable.” That’s been magnified for her son, who turned 10 this spring—his second pandemic birthday—and is too young for the COVID-19 vaccine. When they first returned to church, he was “hyperventilating,” Tolman says. “He’s struggling a lot with anxiety, and he’s been struggling with people and in person, especially with them not wearing masks in public places.”

Tolman, a teacher at Arlington ISD, returned to work in person a year ago, but her two kids stayed home with her husband, a home health aide who works nights, attending classes virtually for most of the school year. Tolman had been especially worried about the health of her husband, who is diabetic and had a heart attack early last year. But remote learning was a challenge for both kids, especially their daughter, who has an intellectual disability, Tolman says. So after her husband was vaccinated, they decided to send her back in person for the last few months of the school year. Once Tolman got the vaccine, their son went back too.

But he soon started having symptoms like blurry vision, which a neurologist attributed to stress. “Basically, he’s just so anxious that it’s causing physical symptoms,” Tolman says. After more than a year of feeling very isolated, “being just thrown back into it and being put in a class with 25 other kids in small quarters, even though they did have COVID procedures, it really affected him. Just being in a doctor’s office or a church or a building where there’s lots of people around—he just hasn’t been used to that because I’ve kept him very isolated, to try to protect him.”

The family is still cautious, but being vaccinated has made Tolman more comfortable—though she wants to continue wearing a mask in the future because she says she’s never been less sick than this past year. She and her husband are able to go out on dates now, including a recent excursion to a small group painting night, while their kids went to an overnight camp for a week this summer. In July, they all took their first trip since the pandemic began, to a family reunion in Idaho; they rented a sleeper camper and made a road trip of it, through national parks where there were outdoor activities and more open space.

Tolman is looking forward to teaching fully in person this fall, with a new job starting an early college health science program at a different school. But she worries about her son. “I’m hoping with the summer and with him going to camp and kind of being not so structured, we’ll be able to prepare for the fall,” she says. But he’s starting at a new, much larger school, which like all Texas public schools, is banned under Governor Greg Abbott’s executive order from requiring masks. Unlike other school districts, as of August, his had not announced whether it would defy the order and mandate masks. “He’s already struggling dealing with people,” Tolman says. “I don’t know how he’ll do, if he’s still going to struggle like he did in the spring.”—Sophie Novack

Betty Gibson

Age: 83

Profession: Retired Bookkeeper

Location: Wichita Falls, Wichita County

Betty Gibson is on the move. The octogenarian great-grandmother of 13 spent most of past year alone inside her Wichita Falls home to avoid catching COVID-19. She gave up traveling, eating out, and visiting with family, relegating herself to a solitary existence where she was lonely but safe. It’s not something Gibson will ever do again: She recently decided to leave her 3,000-square-foot, three-bedroom house to live next to her granddaughter on family land in Terral, Oklahoma, just across the Red River from the tiny Texas town of Nocona.

“I thought I’d be here till I died,” Gibson said in July, as she packed up the living room of the home where she’d lived for 24 years. Moving at age 83 is a daunting endeavor, she says, but it’s not as scary as the idea of spending another year isolated from her entire family. “I thought, ‘Well, if I’m ever gonna do it, now’s the time,’” Gibson says. “I won’t say this in front of the great-grandkids, but I don’t have that many years left.”

Gibson put her house on the market in June, and thanks to a red-hot, pandemic-fueled housing market, it sold after just three days. The new owners, who are moving from Florida, paid more than the asking price. That meant Gibson had to skedaddle. She keeps a tidy house but still opted to hire a company to help clear out some accumulated junk, and they hauled out more than a ton of material from the attic. “I could not believe the amount of stuff,” she says. “They said there were five—five—brand-new trailer tires. We didn’t have a trailer!”

The process has doubled as a way to make up for lost family time. Her son and daughter-in-law drove in from Amarillo and spent two days helping fill boxes, and a granddaughter stopped by often to see her—visits that would have been untenable just six months before. In other good news, Gibson welcomed another great-grandson into the world in mid-July.

The move notwithstanding, Gibson’s life has regained some sense of normality. After idling for weeks on multiple waiting lists, she was vaccinated early this year at the North Texas State Hospital, a state-run facility where the local health department administered vaccines to the general public. Now Gibson sometimes enters the store instead of picking her groceries up curbside, and she occasionally even goes out to dinner. When she turned 83 in June, her friend down the street called to ask, “Can we go out to eat yet?” Gibson agreed, and she and her friend dined at Texas Roadhouse. The new Delta variant of COVID-19 “crosses my mind,” Gibson says, but she’s not as worried as she was last year. She says she’d gladly go back to wearing a mask if necessary.

It’ll be a while yet before Gibson is able to move to Oklahoma to be with her granddaughter, her granddaughter’s husband, and two great-granddaughters. Her home is not yet built—the foundation work was delayed thanks to a particularly wet summer. It’ll be around Thanksgiving before she and her three dogs can take residence in the new 1,700-square-foot structure. In the meantime, she’s living in a small apartment in Henrietta, just east of her old home, with her belongings in storage. Her two great-granddaughters in Terral, ages 7 and 12, are already eager to see her. “Ma-maw, I wish they’d get your house finished so you could get over here!” one of them told her this summer.

“It’s a big adventure,” Gibson says. “I’m gonna enjoy the heck out of it.” —Christopher Collins

David Ceron

Age: 45

Profession: Author

Location: McAllen, Hidalgo County

For the past year and a half, David Ceron has watched—first from afar and now up close—as his mom, Gregoria Ceron, became a different person. He caught glimpses of that change through the window of her nursing home last summer, as his family stood outside to celebrate her birthday and Mother’s Day, separated by a sheet of glass. He saw her confusion deepen in brief moments together this winter, as she wondered why David had stopped visiting her in person the way he used to. But the reopening of her nursing home to more regular visitors this spring after almost a year of lockdown put what David says is the toll of prolonged isolation on his 91-year-old mother in stark relief.

“Before COVID, I would see how some of the patients there who rarely got any visitors, you know, how mentally fragile they were,” he says. “I didn’t realize how big of an issue that was until this one year with COVID, where I just saw my mom’s mental health deteriorate so much just in one year. And I mean, physically, I don’t know how much time it has taken away from her.”

David now visits his mom every day around lunch. If he goes during a meal, he can try to coax her to eat. In recent months, Gregoria, who has diabetes, has been refusing food, prompting a concerned call from the dialysis clinic saying her protein levels were too low. David says she’s more likely to eat if he’s feeding her instead of the nursing home staff, but she’s been sleeping so much that some days he has only a few minutes to speak with her. “My conversations with her, they’re not the same, you know. She talks about people I don’t know; I don’t know who they are and I don’t even know if she knows who they are.” Lately, he says, she’s been asking after David’s sister Mary more and more often; Mary died in 2014.

As David has worried about his mother for the past 18 months, the coronavirus has worked its way through his family. Three of David’s sisters got COVID-19 last spring, along with his brother-in-law, who was hospitalized, and his baby nephew. Last summer, his mom got sick, and he worried she wouldn’t survive. Then his daughter got COVID-19 in November. In late January, the day before his mom got her second vaccine dose, David tested positive in a routine check required to visit the nursing home.

Now that David is fully vaccinated, he’s hoping he’s able to go back to schools and libraries in person in the fall, to give readings of a children’s book he wrote a few years ago: The Adventures of Exo and Cy. A former teacher, David wrote the book to encourage kids to exercise to prevent diabetes, which is rampant in the Rio Grande Valley, where he lives, and in David’s own family. He, his mom, and all his siblings have diabetes, and he lost a brother and sister to the disease. During the pandemic, he’s been making audio recordings of his book in lieu of in-person events and working on a project with the South Texas Literacy Coalition to have the pages blown up and mounted on large signs along walking trails in several cities in the Valley, starting with Harlingen in August. He’s been motivated in particular by the high COVID-19 risk for diabetics. But he worries the Delta variant may prompt another lockdown.

On a recent afternoon, David got so frustrated that his mom wouldn’t eat anything he cut his visit short. “It’s gotten to the point where I don’t want to see my mom like this anymore,” he says. “She’s becoming less and less like the mom I remember, and it just hurts me too much. You know, I just—I just would rather her not have to suffer anymore.”

Before the pandemic, David used to see other regulars who would come visit loved ones at the nursing home every day, like him. He still pictures one couple in particular: The husband would come visit his wife there for every breakfast, lunch, and dinner. “I remember that day when they told us—literally, it was one day from when we went to visit to the next where they told us that they would not be allowing visitors anymore,” David says of the COVID-19 lockdown. “We had just literally hours to figure things out, because they were going to stop visitation. And I remember that man. I haven’t seen him since. But I mean, he was just so devastated, because she was so dependent on him. I haven’t seen him since.” —Sophie Novack