Abie Yogo Darsono and ten of his colleagues are staring at a television in the Disaster Guard Team command room on the seventh floor of the Emergency Ambulance Service (AGD) building in Central Jakarta. An action film is playing: The Bourne Identity.

“In the time of the pandemic we never watch the news,” says Abie. “It just makes us scared and stressed. We watch action films to make us relax.”

At around 11 p.m., a yell from Abie’s colleague pierces the air. “There is a mission!” shouts Bagol, one of the field coordinators on duty that night. “There is a suspected coronavirus patient at Cilincing Regional Hospital. Leave immediately, they’re waiting for us.”

Abie is also on duty. He is a veteran ambulance driver and paramedic who joined AGD in 2004, having graduated from the Husada Karya Jaya Nursing Academy in Jakarta in 2003. By now, 40-year-old Abie could hold a high-ranking position at AGD, but he has always refused promotion—preferring instead to keep working in the field. “I prefer to work on the streets,” he says. “It’s like an adventure. If you work in an office you can get bored, just staring at the wall.”

The command room in Indonesia’s capital is like a military barracks. There are two sets of bunk beds, foldable mattresses on the floor, a kitchen, a lounge and two bathrooms. Once the room was mostly unused. But since the COVID-19 outbreak in March, the room has been occupied by almost 50 members of the Disaster Guard Team who work in three eight-hour shifts throughout the day.

Following the call to the hospital, Abie immediately goes to the communal dressing room and takes out a set of full-body personal protective equipment (PPE). After washing his hands thoroughly, he puts on a hazmat suit, boots, protective glasses and three-layers of medical gloves. Finally he straps on an N95 mask.

Swelling Ranks of the Disaster Guard

Working with Abie that night is a 23-year-old emergency medical technician (EMT) named Dimas Ilham. Abie walks toward the white and green retrofitted Toyota Hiace van parked in the AGD front yard as Dimas checks all the medical equipment in the back to make sure it is functioning properly.

The equipment in the ambulance is comprehensive: Hamilton-brand ventilators, heart-monitoring devices (electrocardiograms), oxygen tanks and so on. Abie jokes that the price of all the equipment is more expensive than the price of his car.

Within a few minutes, Abie and Dimas are on the deserted streets of Jakarta—it is like a dead city in an apocalyptic film. Abie’s hands are steady holding the steering wheel. There is no anxiety on his face. The ambulance speeds through the night at 80km per hour—a speed usually impossible to reach on the jammed streets of Jakarta before the pandemic. The sound of an occasional siren breaks the silence of the night, reminding passing motorists to make way.

The Emergency Ambulance Service (AGD) was established in the early 2000s to assist disaster response teams, such as the National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB), the National Search and Rescue Agency (Basarnas) and the Indonesian military. Previously, the Disaster Guard Team (a special unit within AGD) was semi-inactive as it only handled extraordinary events or natural disasters on a national scale. Disaster Guard members are trained in evacuation skills as well as medical expertise and, when a national disaster occurs, they are always sent to the front lines.

When a devastating tsunami hit Aceh Province in 2004, Abie worked in the field for a month, helping with the evacuation process and recovery. He also evacuated the bodies of the Sukhoi Superjet 100 passengers when the plane crashed into Mount Salak in West Java in 2012, and worked in Banten Province when it was hit by a tsunami in December 2018.

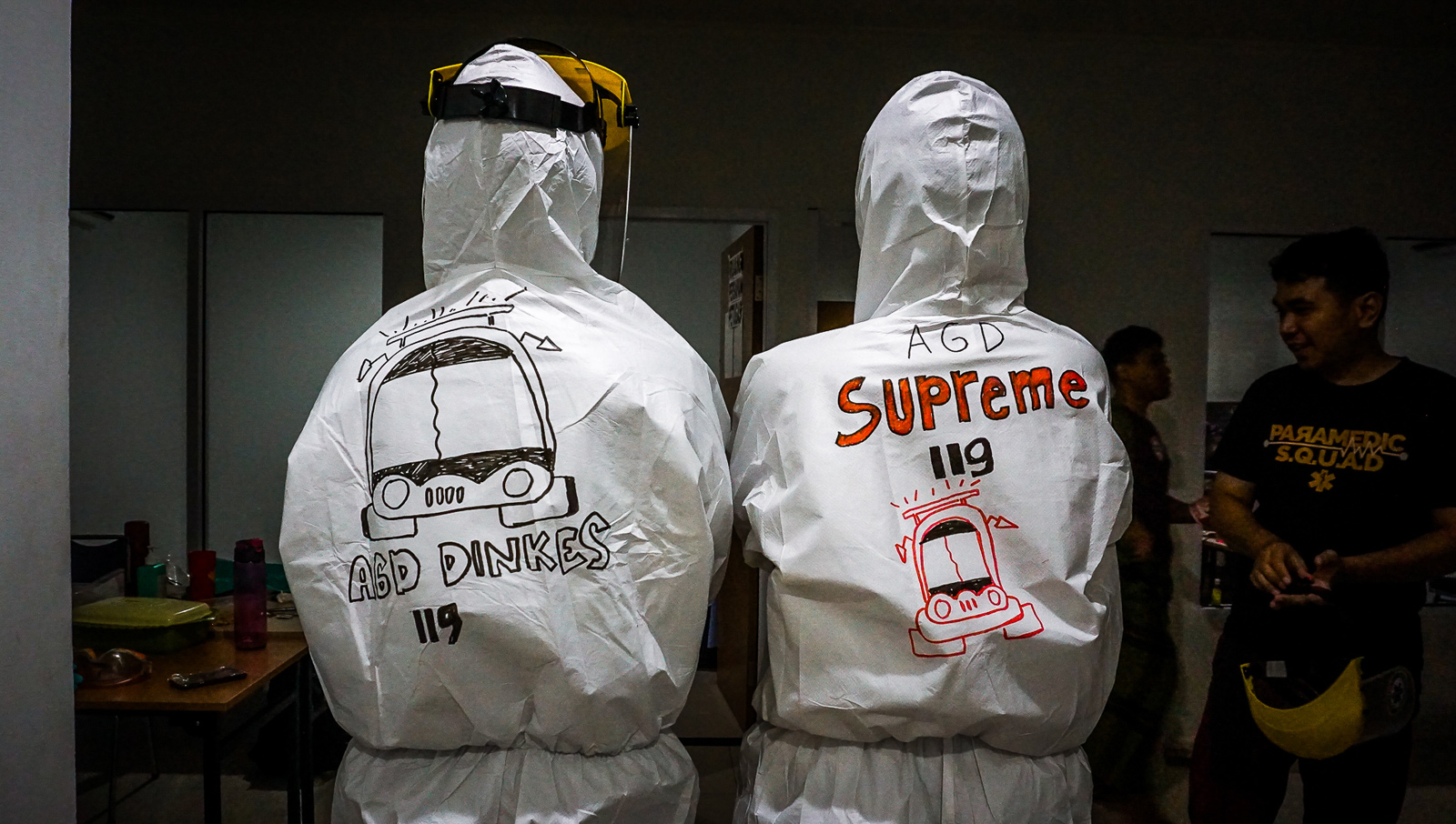

“It’s like a ritual. Hope, prayers and slogans written on our PPE. It’s a reminder that there is still hope and optimism even in the middle of a pandemic.”

The Jakarta Ambulance Service reactivated the Disaster Guard Team in March 2020, shortly after President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo announced the first two positive COVID-19 cases in Indonesia. The AGD Disaster Guard Team initially had no more than 10 members, but as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the team’s ranks have swelled to 50 people, who come from across the Department of Health.

Previously the AGD unit existed in a kind of vacuum due to financial and bureaucratic issues. In July 2016, the Ministry of Health launched the AGD service anew with the emergency number 119 in major cities as a form of emergency medical service. In order to operate effectively and efficiently, AGD is under the auspices of the provincial Health Office. But still, after two decades of existence, various problems still hamper this humanitarian service.

Transporting Coronavirus Patients

In Jakarta, with a population of nearly 10 million, AGD’s first responders only have 67 ambulances and 25 motorbikes. The average response time of an AGD ambulance ranges from 30 to 40 minutes. Ideally, an ambulance response time is under 15 minutes, Dr. Iwan Kurniawan, the Jakarta head of the AGD, tells New Naratif. Not infrequently, many people are disappointed with AGD services, saying they have to wait too long and prefer to use private vehicles or taxis to seek medical treatment, he continues.

Indonesia has a chaotic health system at best. The country had 9,754 puskesmas (local health clinics) and 2,488 hospitals in 2015, according to data from the Ministry of Health. The World Health Organisation (WHO) says that on average Indonesia only has one hospital bed per 1,000 people. There are only four doctors per 10,000 people.

Not all hospitals in Indonesia have ambulances with WHO-standard equipment. Most ambulances only have minimal equipment such as a first aid kit. As a result, according to WHO data, 5.8 million people die each year due to poor emergency treatment (pre-hospital) in middle to lower income countries, including Indonesia.

“We are clearly lacking,” says Iwan. “We have appealed to the Department of Health and the ministry, but there are still many obstacles.”

During the pandemic, the number of ambulance service requests to AGD has dropped by 10 percent, because many people are reluctant to go to the hospital other than in a dire emergency.

Ideally, says Iwan, there would be one ambulance for every 5 kilometres of road. This calculation means that the AGD in Jakarta requires a total of 200 ambulances to serve the city optimally. Iwan says this would add 100 personnel this year. AGD has more than 700 employees consisting of staff and field officers. Each month AGD is only able to service 4,000 requests—from accident victims on the streets to transportation services from home to hospital. That means that, on average, one AGD ambulance car unit can only handle approximately two patients per day, while management has set a target of servicing 8,000 requests per month. AGD is aware that many people are not familiar with or willing to use their free ambulance services. They have tried various ways to advertise their services, from creating AGD TV stations to promotions through social media accounts.

As the coronavirus has spread across Indonesia, with Jakarta at the center of transmission, AGD has become increasingly overwhelmed.

Jakarta recorded 6,798 cases and 501 deaths (the highest number of both cases and deaths in Indonesia) as of 26 May. Total COVID-19 cases in the country have reached 23,165 with the number of deaths topping 1,418, according to the WHO. However, many suspect that the COVID-19 transmission rate is actually much higher due to a lack of aggressive testing and lax social distancing measures. Only 264,098 tests have been conducted on some 188,302 patients to date, out of a population of over 260 million people.

During the pandemic, the number of ambulance service requests to AGD has dropped by 10 percent, because many people are reluctant to go to the hospital other than in a dire emergency, for fear of being infected by the virus. But AGD still has difficulty servicing calls because of a shortage of vehicles. Currently ambulance requests are dominated by hospitals that want to refer a patient to another hospital and need transportation.

“Every day there are queues, and we say that honestly to the public. If they don’t want to wait until the ambulance arrives, what can I do? This is the situation.”

“The demand for [ambulances] is now around 3,500 a month,” says Iwan, AGD’s Jakarta head. “That number is mostly still related to coronavirus cases. Because many people with other diseases prefer to take care of themselves at home if it’s not too severe.”

As of the end of May, AGD only had a total of five special ambulance units to handle COVID-19 patients. A COVID-19 ambulance is specially designed with a divider between the driver’s seat and the patient to minimise contact. The ambulance is also equipped with a HEPA filter to circulate air and prevent the spread of the virus.

Because of the limitations, AGD has queues of dozens of requests for ambulances every day. In addition to the minimal number of ambulance units, not all ambulances are equipped to transport patients who may have coronavirus. “Every day there are queues, and we say that honestly to the public. If they don’t want to wait until the ambulance arrives, what can I do? This is the situation,” says Iwan.

Inside the Emergency Call Centre

Of all parts of the Jakarta AGD building, the command centre on the fourth floor is the busiest. In this room, operators process incoming calls to the 119 number from all corners of Jakarta. All the tables here face a giant screen that displays CCTV feeds from Jakarta’s streets in real time. On each table sits a computer screen that displays a map of Jakarta with several glowing red dots that show the location of the ambulance units which are equipped with a GPS tracker.

After asking the patient’s location and health condition, an operator glances at the Jakarta map on the screen, looking for the nearest ambulance and hospital before returning to the telephone line to ask the patient to be…patient. The ambulance will be sent to the location immediately, says the operator. The operator then contacts the nearest ambulance officer, while explaining the patient’s condition and providing location details.

There are 44 call centre employees who work in two 12-hour shifts, 24 hours a day. These employees are required to have a nursing academy diploma, because they must conduct an assessment of the patient’s condition via telephone before sending an ambulance to their location.

“If we have adequate ambulance services and optimal hospital support, maybe a lot [of people] can be saved.”

In a back corner of the command centre, Dr. Bara Purnawan Putra is sitting and watching a computer screen. He’s been a medical worker for the past eight years and served in various remote areas, from South Kalimantan to Central Java. He aspired to become an architect, but his fate took him to the medical faculty of the Christian University of Indonesia in Jakarta. Bara joined AGD two years ago.

It is not even afternoon, but there have been 47 incoming calls to the 119 call centre since 7 a.m. Not all calls can be dealt with, says Bara. “We don’t have the resources to answer all requests. But we try as much as possible. If you get scolded by people, that’s normal,” he adds.

Bara says that if the health system in Indonesia can be optimised, the average death rate from coronavirus—now around 6.1 percent of the total confirmed cases—should decrease. The number of patients under observation for coronavirus in Indonesia is now more than 30,000. In Jakarta, there are over 6,000 patients being treated and burial figures recorded by the DKI Jakarta Provincial Government show a significant increase compared to the months before the pandemic. In April 2020, the Jakarta Provincial Government recorded 3,264 funerals compared to 2,790 in April 2019.

“If we have adequate ambulance services and optimal hospital support, maybe a lot [of people] can be saved,” Bara says.

As the command centre coordinator, it is Bara’s responsibility to ensure all call centre operations run smoothly. He must ensure that each of his subordinates carries out detailed screening procedures to lessen the risks of them getting sick. Hundreds of medical workers throughout Indonesia have become infected with COVID-19 because patients have been reluctant to tell the truth about their condition. Some 17 medical workers in West Kalimantan tested positive for coronavirus contracted from patients, as reported by Kompas.com. “Dishonesty endangers us in the field,” adds Bara.

His attitude is understandable. On 19 April, an AGD officer named Shelly Ziendia Putri died while under observation for suspected coronavirus. Shelly was treated in two different hospitals for two days before she took her last breath following symptoms consistent with COVID-19. It is not clear how she fell ill, where she may have contracted the virus or if she indeed tested positive for COVID-19—the results of her test have yet to be revealed to her colleagues.

“No one has experienced anything like this. So there’s no point in blaming each other.”

Shelly’s death was a big blow to AGD and her colleagues lined up to pay their respects when the ambulance took her to her final resting place. “It was like losing a family member,” Bara explains. He also admits, however, that blaming patients for being sources of contagion is futile. Sometimes they don’t know their medical history or the symptoms of coronavirus, and the negative stigma surrounding the illness is sometimes the reason why patients are reluctant to speak about it honestly.

Bara understands. This pandemic is a tough test for anyone.

“No one has experienced anything like this. So there’s no point in blaming each other,” he says.

Separated From Family

Satria, a resident in West Jakarta, prefered to use a taxi booked through a mobile app when bringing his father to Hermina Hospital at the end of March. His father, Maruf bin Khasan, was 63 years old and had a history of respiratory problems when he suddenly complained of breathing difficulties. “We just panicked,” remembers Satria. “We didn’t think of calling an ambulance. We thought it was faster to rent a taxi online.”

Maruf was treated and placed under observation. Two days later, he died and was buried according to COVID-19 protocols at Tegal Alur Cemetery in West Jakarta.

Dr. Mahesa Paranadipa from the Indonesian Health Law Society (MHKI) says that although ambulances do not offer comprehensive health services like hospitals, they are still an essential part of the health system. “Even though they are only for patient transportation, they are still important,” he tells New Naratif.

“In the era of COVID-19, an ambulance is like a feared object. Nobody dares approach.”

According to Mahesa, the Indonesian health service (Dinas Kesehatan) could coordinate with private ambulance services and humanitarian organisations in conjunction with AGD Jakarta to bolster and share resources. “Then just training and debriefing for officers who perform the ambulance services is needed in order to minimize the risk of transmission.”

Twenty minutes after leaving the AGD building, the ambulance driven by Abie arrives at Cilincing Regional Hospital in North Jakarta. The hospital is quiet. There is barely any visible activity. Abie reaches for the radio to communicate with the hospital directly.

“In the era of COVID-19, an ambulance is like a feared object,” Abie says. “Nobody dares approach.”

After getting permission from the hospital, Abie directs the ambulance towards the emergency room. He immediately goes to the fourth floor, with his colleague Dimas following right behind him. After taking care of all the patient’s documents, Abie loads the man into the ambulance on a stretcher. The 22-year-old patient works as a crew member on a fishing boat and has a fever and symptoms of pneumonia. He is under observation as a suspected COVID-19 case, but Cilincing Regional Hospital does not have sufficient facilities to treat such patients and has referred him to Duren Sawit Hospital in East Jakarta.

There are 153 hospitals with a total of 19,200 beds across Jakarta, and the government has only appointed 13 of these as COVID-19 referral hospitals. Throughout the coronavirus outbreak, the Indonesian government has designated a small number of public hospitals across the country as COVID-19 testing centres, and most other hospitals reject patients with symptoms, or require patients to undergo rapid tests in order to be admitted. If the hospital is unable to handle the patient, they will be referred to a designated COVID-19 testing hospital instead. This makes the role of the ambulance service worker even more crucial in terms of transferring suspected and positive COVID-19 patients from one hospital to another. If not handled properly during transportation, the virus can be spread further.

While on duty, EMTs minimise physical contact with COVID-19 patients as much as possible. But Dimas, who sits in the back of the ambulance with them, still tries to communicate with those he is caring for. “Motivation is important for the patient, we need to keep them calm,” he says.

“Every day we transport COVID-19 patients, so now it feels normal. Now we are more relaxed, but still careful.”

It takes between five or six hours for an ambulance crew to transport a patient. Sometimes the team has to wait at the hospital, which increases the risk of exposure. After completing one trip, the ambulance must be taken to the decontamination centre located in Sunter, North Jakarta. At the centre, the ambulance is sprayed with disinfectant and zapped with UV light. PPE clothes and other equipment are wrapped in plastic and disposed of in accordance with hazardous waste protocols. The ambulance workers should get a check-up and a rapid test after each assignment but, due to a shortage of rapid test kits, the EMTs often forgo the tests according to Abie. The decontamination centre is the only one in Jakarta that serves public transport and ambulances. Often a long line of vehicles can be seen snaking out of the centre which operates around the clock.

“At the decontamination centre officers can eat and rest after work,” says Dimas. “The AGD also provides hotel rooms for officers who want to isolate themselves if they have COVID-19 symptoms.”

Dimas joined AGD East Jakarta two years ago. When the coronavirus outbreak hit Indonesia, he was called to the central AGD unit to join the Disaster Guard. For young officers like Dimas, treating coronavirus patients is a kind of nightmare, because there is no guarantee that he will not be infected. But slowly, he has been able to put his concerns to one side.

“Every day we transport COVID-19 patients, so now it feels normal,” he says. “In the beginning, the fear and worry made it easy for us to get very down. Now we are more relaxed, but still careful.”

Struggling in the middle of a pandemic has become routine for Abie and his co-workers. Since March, some of the members of the Disaster Guard have chosen not to return home for fear of carrying the virus to their families.

“During natural disasters we know when there will be an end to the tragedy,” Abie says. “But during an outbreak like this, we don’t know how long [the response] will take.”

Since the pandemic, Abie says that he hasn’t been able to see his wife and 8-year-old daughter, who are now staying at her parents’ home in Cikarang, West Java. He can only see them on a phone screen. Abie, who works six days a week followed by two days off, now lives in the Disaster Guard command room. He has no plans to return to Cikarang to see his family.

“My daughter sometimes asks ‘When is daddy coming home?’” Abie says, looking tired. “I always say to her, ‘daddy is on duty helping people, he can’t come home just yet, pray for him.’”

“She says she understands.”

The post Stretched Thin: Inside Jakarta’s Ambulance Service appeared first on New Naratif.

New Naratif explains and explores the forces which shape how Southeast Asians live and understand our region. Learn more at https://newnaratif.com/hello/.