Photographs by Ilona Szwarc

Sid Miller, the Texas agriculture commissioner, sat atop his stallion Smokey and faced the camera. It was Saturday, August 1, 2020. Miller had a message to share.

“Good morning, patriots,” Miller began, raising the coiled lasso in his right hand by way of greeting. “I don’t know about you, but I’m getting tired of all these surprises coming out of China. First it was the Chinese virus, then we had the murder hornets, then we had to close the embassy in Houston because of espionage … Now we’ve got all these mystery seeds coming in in the mail.”

It was the seeds that Miller wanted to speak about. By then, news of the seeds had been circulating for several days. Packets were turning up at homes across the United States; residents of every state would eventually report receiving them. Their address labels and Customs declarations indicated that they had been sent from China. The contents were usually described as an item of jewelry—something like “rose stud earrings”—but inside would be a small packet of unidentified seeds. There was no evident reason why particular people were receiving particular seeds, or why people were receiving seeds at all.

Miller advised anyone who received one of these packages to handle it with extreme care. “Treat them like they’re radioactive,” he said. As Smokey flicked his tail, the commissioner laid out what he considered to be the worst-case scenario: “My greatest fear is that someone will open these packages up—open these seeds up—and be infected with a new virus of some kind.” If you found yourself in possession of such a package, Miller said, you should email him immediately, and he would send an inspector to pick it up.

“You don’t want to cry wolf unless there’s a wolf at the door,” Miller told me when I called recently, “but I have a $100 billion industry here just in Texas to protect.” In the face of something so odd, Miller’s instincts arced toward suspicion.

“We didn’t know what in the world was going on,” he said.

Listen to Chris Heath discuss this piece on the Experiment podcast.

Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google Podcasts

If someone had wanted to invent a surreal provocation designed to unnerve Americans in the summer of 2020, it’s difficult to conceive of a better one than a deluge of unsolicited Chinese seeds. For one thing, in those first months of the coronavirus pandemic, references to China triggered associations—rational or otherwise—with contagion. For another, these objects were invading private spaces at a time when most of us were newly hypersensitive to our surroundings. And what was happening was something that was hard to explain, in a moment when so many fears that might have once seemed far-fetched were either being realized or, at the very least, suddenly sounding plausible.

Even people who considered themselves above the lure of alarmist theories had to take the seeds seriously. Irrespective of why they were appearing at people’s homes, their very existence—as biological matter of unknown origin—constituted a problem. This reality acted as a narrative anchor for what might otherwise have seemed to be fanciful media stories. The government genuinely was concerned. Whenever someone wanted to tell the story of these Chinese seeds, a local or federal agriculture spokesperson was always available to expound on how unknown seeds of foreign origin were, until proved otherwise, a threat to American agriculture or even the whole North American ecosystem. Advice soon circulated that the seeds should not be planted, burned, or even disposed of in the trash, given the possibility that they could germinate and disseminate from a landfill. And if you received any, the government would definitely like to know about it.

This combination of factors—a mystery, multiple anxiety triggers within the perpetual panic chamber we live in, and a bedrock empirical reason this had to be taken seriously—encouraged a proliferation of wild theories. Here, for instance, are some of the explanations that I saw floated, for the most part not at the rabidly conspiratorial fringes of the internet, but on gardening-group and state-agriculture-department Facebook pages: that the seeds were Chinese bioweapons, laced with viruses or poisons, or that they were engineered through genetic manipulation or nanotechnology (threads picked up in a Tucker Carlson Tonight segment with the chyron COULD MYSTERIOUS SEEDS BE BIOLOGICAL ATTACK?); that they were part of a “deep state” strategy to control our gardens, or a false-flag operation to discredit China; that they were a Chinese cure for COVID-19 suppressed by Big Pharma; and that they would grow to feed swarms of invasive murder hornets.

A year later, however, no monstrous mystery vines are strangling America’s cornfields. The seeds mostly stopped coming, and the world moved on. But I wanted to know: What was it all about? So I decided to reimmerse myself in the giddy anxiety of last summer. I planned to speak with some of those who had received the packages, dissect the hullabaloo around them, and construct the definitive account of the seeds-from-China moral panic.

It seemed straightforward enough. I had no idea.

It is perhaps ironic, given how many people assumed that America was being targeted, that news of the seeds appears to have first surfaced in the United Kingdom.

On the morning of June 5, a woman named Sue Westerdale, who lives in a small town in northern England, posted in the Facebook group “Veg gardening UK” about something peculiar. She had received a mysterious packet of seeds from China, described on the envelope as “ear studs,” and wondered whether this had happened to anyone else.

John Roberts, a retired railway worker who lives 100 miles to the south, replied within the hour; he’d gotten some seeds the previous week. He’d called the local police, who came and picked them up, telling Roberts they’d investigate the seeds and then burn them. Other stories followed.

Over the next few weeks, these British gardeners became exasperated. Amid plenty of thoughtful debate and the occasional xenophobic comment (less than 10 hours after Westerdale’s post, someone wrote: “I reckon it’s some kind of covert biological thing from China that will affect all our plant life and we’ll all die of starvation, then China will take over the world”), there was a sense of frustration that something important was going on and no one was listening. People in “Veg gardening UK” and other groups contacted the British agricultural authorities. They contacted celebrity gardeners and members of Parliament. They contacted the media. One person, tweeting under the name Tinkerpuss I will NOT be silenced! (apparently a beautician named Charlotte), was particularly vociferous, firing urgent messages at British newspapers, to no effect.

Credit for finally breaking the story circles back to the Westerdale household. Sue’s husband, Bob, used to be a crime reporter and is now a freelance writer. At first, when his wife told him about the seeds, he didn’t think too much of it. He was used to all kinds of packages turning up at their home; maybe his wife had just forgotten that she’d ordered the seeds. As the weeks passed, though, Bob started to pay more attention. He noticed what people were writing online, and began to wonder whether there might be a sellable angle here, in the way the seeds grafted onto fears of infection. “As a news story, I thought that might speed it on its way, if I’m honest,” he told me—“you know, feeding on that anti-China paranoia.”

Bob pitched the story to an old colleague, Richard Marsden, who works at the Daily Mail. Marsden did some of his own reporting, and on July 18 a small item appeared. “Gardeners Sent Sinister Seed Packs From China,” the headline read, introducing the idea that what was happening was both a puzzle and a threat.

These “sinister seed packs” were also arriving at American homes—the U.S. Department of Agriculture would retroactively date the earliest related package that it was aware of to June 2. Aside from a few bemused comments online, though, there’s little indication that anyone took too much notice until Lori Culley, a grandmother in Tooele, Utah, just west of Salt Lake City, succeeded in sounding the alarm.

Culley has an autoimmune disease and avoids leaving her house, so she’s accustomed to receiving most of what she needs by mail. But one package that showed up in the middle of July was a surprise. It appeared to have come from China, and its contents were described as an ornament, though one perhaps hitherto unknown in the gem trade: “Dogweed Stud earrings.” Inside were largish, almost bulblike brown seeds. Culley wrapped two in a wet napkin and left them on her windowsill. “I was going to see what grew,” she told me.

A couple of days later, on July 21, a second package arrived. This one, its contents described just as “jewelry,” contained tiny near-black seeds. Now Culley was worried. That evening, she posted photos of the seeds and their packaging on Facebook, alongside a photograph of the Daily Mail article, which she had found online.

Within a few hours, eight people had commented to say that they, too, had received seeds. Culley also posted in a Facebook group that she had started in April for, as she characterized it, “ladies going through what I was going through: COVID, I live alone, we’re just depressed.” More voices chimed in.

Something weird was happening, Culley told me, something that felt potentially dangerous. She used to work as a supply specialist for the Army, she explained, and when she took that job, she also took an oath to “always protect my country.” Now she felt she was duty bound to act.

She reached out to the local university-extension office, where agriculture experts offer advice. But she felt like they brushed off her concerns. Undeterred, she DMed four local TV stations on Facebook. Three didn’t respond. The fourth, Fox 13, replied immediately.

A reporter named Adam Herbets was assigned the story. He called Culley to arrange an interview. Herbets also reached out to an entomologist he knew at the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food. By the time Herbets arrived at Culley’s house, an official was already there to pick up everything Culley had. (This was now five packs of seeds, including three dropped off by Culley’s daughter, Kacee, quite independently a recipient too.)

For the Fox 13 cameraman, Culley acted out picking up her mail—the traditional camera-angle-from-the-inside-of-the-mailbox shot—then stood, masked, on her porch, talking about the seeds. “We just can’t be too vigilant,” she said. “There’s too much crazy stuff going on in our world anymore, and a lot of it’s coming from China.”

Two days later, on July 24, the first official statements began to appear on state agricultural websites, advising the public about what was happening and what they should do. The advice was sometimes contradictory. The Washington State Department of Agriculture initially counseled that if the seeds were double-bagged, they could be placed in the trash, while Utah proposed killing the seeds by “baking them at 200 degrees for 40 minutes.” Soon the advice coalesced: The seeds should be sent to a state facility or picked up by state officials.

Whatever was going on, the USDA was determined to be on top of it. “Early detection is of fundamental importance,” says Osama El-Lissy, the deputy administrator of the Plant Protection and Quarantine Program in the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, and the man who headed up the response. Within days—in the same period that a cavalcade of local and national media stories appeared—the agency’s count of the mystery packets jumped from a dozen to more than 1,000. In most cases, the seeds were collected state by state and then forwarded to one of 13 federal facilities. Those from New York, Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Illinois, and Wisconsin arrived at an inspection station at JFK International Airport for the attention of Keith E. Clancy, a botanist and identifier.

Wearing a face mask and latex gloves, Clancy examined what was inside each packet, either with a hand lens or under a microscope. He has been doing this job for 17 years, and most of the seeds he could identify by sight. They were beans, melons, cucumbers, marigolds, sunflowers, peas, lentils, carrots, radishes, kale, cabbages, ornamental grasses, roses, morning glories, and many other plants. They kept coming and coming. (To date, government botanists have identified some 560 different species from these seed packets.)

Clancy was on the lookout for contaminants. One day, he found four seeds of dodder, parasitic plants that can choke crops such as carrots and potatoes—but nothing to make the USDA tremble.

The few seeds Clancy could not identify, he forwarded to national botanists in Maryland. There, they did molecular testing that could pick up evidence of any viruses, bacteria, or other organisms. They grew the seeds in their quarantined facilities, looking for any signs that they may have been genetically modified. They also mapped where the seeds had been sent, looking for any correlation with crucial agricultural infrastructure or key natural resources. “We have one of the most sophisticated safeguarding systems, probably in the world,” El-Lissy told me. If something nefarious was happening, they were doing all they could to find it.

The one rule on which there was consensus from the beginning was this: Do not plant the seeds. Problem was, some people already had. The poster child for this—insomuch as a 70-something retiree from the oil and gas industry can be a poster child—was a man named Doyle Crenshaw.

Crenshaw, who lives in Booneville, Arkansas, was watching Channel 5 in late July 2020 when he saw an item about Chinese seeds. He knew just what they were talking about. A couple of months earlier, he’d received precisely such a package: “studded earrings,” Chinese writing on the envelope, light-colored seeds inside. They’d arrived at the same time as some “exotic zinnia seeds” that Crenshaw had ordered, but he hadn’t a clue what these other seeds were. He thought, Well, I’ll just plant them, see what happens.

He cleared some space in the raised beds where he and his wife grew lettuce and tomatoes, and every couple of weeks applied a booster of MiracleGro. That seemed to work. First came bright-green five-lobed leaves, then orange flowers, and then some strange kind of fruit that started out greenish but soon turned off-white.

“I ain’t never seen anything it looked like,” Crenshaw told me. “It was about 14 inches long and four or five inches round.” He broke one open; its flesh smelled sweet. His grandson wanted to taste it, but Crenshaw vetoed this. “Nah, better not.”

Crenshaw dutifully contacted Channel 5. It was hardly surprising that the station, upon hearing that a local man had not only planted mystery seeds but now had fully grown plants laden with mystery fruit, was interested. Crenshaw was filmed standing next to the plants, explaining about the MiracleGro and how “they just started growing crazy.” As the camera panned over the leaves, a voice-over explained: “Experts are unsure what this plant really is, but the concern is it turning out to be an invasive species, which could hurt local agriculture.”

After the segment aired, “I was a celebrity in town—everybody recognized me,” Crenshaw told me. Reporters started calling from “Dallas, Mississippi, Oklahoma City, Kansas, Canada … one from France.”

Eventually, he’d had enough. “It got to bugging me,” he said, “having to talk so much on the phone … It’s the same story every time—it ain’t going to change.” Crenshaw told me all this quite amiably, as though the experience had confirmed that there are kinds of absurdity out in the world that he had previously only suspected.

It was Crenshaw’s doctor who told him that he was famous on the internet. That was true, though if Crenshaw had looked closely, he might not have liked what he saw. One easy way to spin this tale was to cast Crenshaw in the role of the fool—the naive rural fool. No matter that Crenshaw had planted the seeds long before there was any specific advice not to, or that he was far from alone. The Arkansas Plant Industries Division told me that it dug up plants in about 30 such cases. At one point, the state was deploying 25 agriculture inspectors, 13 Bureau of Standards inspectors, five pest-control inspectors, and two inspectors of honeybee apiaries to deal with these seeds and any resulting plants.

An official bagged up Crenshaw’s mystery plants and took them away. A few days later, Crenshaw received a call from Little Rock, letting him know that what he’d been growing had been identified: It was Chinese watermelon. To be precise, Benincasa hispida, a vine whose fruit is also known as a wax gourd or winter melon.

By the time officials came to pick up the plants, Crenshaw had received a second unsolicited packet of the same seeds. He handed them over as well. Three days after that, a third packet arrived. What did he figure was going on?

“Oh, I had no idea,” he told me affably, as though I were wasting both his time and mine by asking. “Nor did I care.”

Doyle Crenshaw was one of the most prominent seed recipients, but plenty of others enjoyed or endured a moment of celebrity last summer. I spoke with several, but the most remarkable story I found came from a woman named Chris Alwhite, who had posted a single sentence on the Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry’s Facebook page: “I have about 50 of these packs from china.” Before I contacted her, I presumed that this would turn out to be a joke, or an exaggeration. I certainly didn’t imagine that it would be true.

And it wasn’t—or not exactly. After the seeds stopped arriving, toward the end of last year, Alwhite gathered all the packets, put them in a big plastic Walmart bag, and stashed them in a drawer in her Shreveport home. At my request, she opened the bag and counted the packages as I stayed on the phone. It took a while.

“Five hundred nineteen,” she eventually declared.

Alwhite explained that the seeds began to arrive in early 2020. She was a member of Facebook gifting groups, a phenomenon in which people socialize online and buy one another items from their Amazon wish lists. On her list, Alwhite had maybe 25 different vegetable, fruit, and flower seeds—“when my grandbabies had come up for the summer, I had promised them a big garden,” she explained to me—so she wasn’t surprised when seed packets started arriving. But she soon realized that something wasn’t right.

As she understood it, items sent via the gifting group would come with a name, or, if the donor wanted to stay anonymous, a barcode so that you could thank your benefactor without knowing who they were. But the packets Alwhite received, labeled as jewelry or wire connectors, had none of those details. And they just kept coming—three or four or five a day. For some reason, Alwhite had become what we might term a super-receiver.

“It went on for months and months and months,” she said. “I just stopped opening them.” Last July, when she heard that others were receiving seeds, she contacted the Louisiana agriculture department. That call didn’t go the way it was supposed to. “They were like, ‘Oh, it’s a hoax … Plant them or toss them, do what you want,’” Alwhite recalled. “That’s Louisiana for you.”

She didn’t follow the advice (which directly contradicted the agency’s public statements asking people to mail the seeds to state labs). “I have pets!” she told me. “For all I know, it’s going to be some eight-foot-tall Venus flytrap in my house. I’m going to come home from the grocery store and find my cats and my dogs all missing.”

I described Alwhite’s experience to El-Lissy; he said that the USDA would be keen to examine her seeds. They would join all the other unexplained seed packages the USDA has gathered since last summer—a collection that, as of June, numbers 19,841. Once all the investigations are completed, perhaps some will be kept for future reference, or be added to the department’s seed library, or be used for training. Anything that is not needed will be incinerated—“the most proper way,” El-Lissy said, “of destroying things like that.”

In late July 2020, a retired postal worker from Massachusetts shared a thought on Twitter:

The 2020 election assistance Trump said he would accept if available is coming RIGHT NOW, not DIRECTLY from China but from surrogates—probably poor Chinese citizens desperate for income. They are mailing seeds to US residents/voters in order to further undermine mail in voting.

Others echoed him:

“China did this to find out which US addresses were still valid for mail-in and absentee ballots!”

“Communist China will mail millions of fake ballots. They already did their test run with toxic seeds to ALL 50 states.”

There were plenty of problems with this theory, beyond the fact that there was no evidence it was true. For instance: If the seeds were related to the U.S. election, why send them to other countries? Why deliver them to all 50 states, most of which would be electorally irrelevant? And what specifically could be achieved—for all the talk of test runs and undermining—by successfully shipping packages to American addresses?

Perhaps that’s why this particular delusion never took hold. But people kept looking for dramatic explanations, as if only something extraordinary could explain something so odd.

And yet one of the strangest parts of the mystery-seeds-from-China panic is that there was never much doubt about why these seeds were sent. The consensus, right from the start, among many government officials, journalists, and comment-section know-it-alls, was that the seeds were probably part of a mundane, illicit e-commerce strategy commonly known as a brushing scam.

Although brushing is a fairly banal form of e-commerce chicanery, it’s also weirdly complicated, counterintuitive, and tricky to explain. Let me try.

In one common, modern-day form, it operates something like this: Chinese companies compete for the highest placements in search listings on e-commerce platforms such as Amazon and AliExpress. Although the algorithms behind these rankings are secret, they are presumed to be affected by volume of sales and positive customer feedback. Some companies try to manipulate the rankings by inventing fake transactions. They, or most likely subcontractors, set up accounts using people’s real names and addresses. The companies then pretend to send something of value to those addresses and post fake glowing reviews under the recipients’ names.

All well and good, in its own crooked way, except that some platforms verify such transactions by requiring tracking data showing that a package has indeed traveled from the company to the customer’s address. That’s where the seeds come in. For the scam to work, a real package needs to be sent. But instead of the more valuable item the company is pretending to have sold, something cheap is substituted—hair ties, say, or plastic trinkets.

Or—it appeared—seeds. If this was brushing, the fact that seeds were being sent was more or less incidental. The seeds might still represent a biological threat—e-commerce hucksters are hardly likely to have researched which species might be appropriately imported into different parts of the United States—but only a haphazard one, not a targeted attempt to disrupt American agriculture, never mind anything more sinister.

These dots don’t seem to have been particularly hard to connect. On July 28, 2020, the USDA said, “At this time, we don’t have any evidence indicating this is something other than a ‘brushing scam.’” Brushing was referred to or described in almost every American news story I have mentioned, even if sometimes as a party pooper turning up to undermine all the melodrama. Sid Miller referred to it in his August 1 horseback video; a guest on Tucker Carlson’s show referred to it the night before; the broadcast that Doyle Crenshaw saw on Arkansas’s Channel 5 on July 27 covered it; the technique was even briefly described in Fox 13’s segment on Lori Culley back on July 22.

Even weeks before that, sundry members of the public appeared to have worked it out for themselves:

TheRealEvanG, on Reddit, June 22: “Sounds like your relative might have been the victim of a brushing scam.”

Becca Clair, on “Veg gardening UK,” June 24: “There’s not really anything to investigate I’m afraid. It’s a well known scam called brushing, and has been going on for years.”

If true, this raises a different question, one that may be more about contemporary media storytelling than agronomic perils: How and why was the great Chinese-seed mystery of the summer of 2020 ever allowed to seem like a mystery at all?

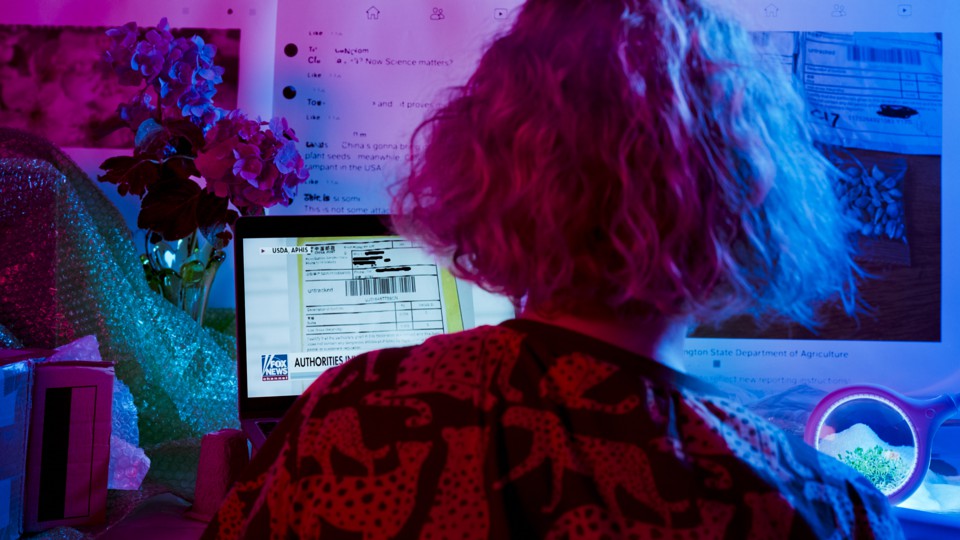

As I tried to figure out what happened last summer, I came across one place where two opposing forces—the imperative of telling the simple, apparent truth, and the impulse toward the rich gratifications of fever and froth—ran up against each other in a way that I found unexpectedly delightful: the Facebook page of the Washington State Department of Agriculture.

This page had somehow become the clearinghouse for reports of seeds from all over the country; a single matter-of-fact post on July 24 received more than 22,000 comments. People shared photos; people shared jokes (“who had magic seeds on their 2020 apocalypse bingo card?”); people freaked out. And, with calmness and fortitude, the page’s moderator strove to moderate:

Jessica Williams: “They need to call it what it is!!! Terrorism!”

Washington State Department of Agriculture: “USDA has no indication that it is anything other than a ‘brushing’ scam.”

Stacie Turner: “Biowarfare via CCP that could cross germinate with our crops and contaminate the food supply?”

Washington State Department of Agriculture: “More likely a ‘brushing’ scam.”

Patty Stroe: “Read the article, that’s what the USDA believes, that the seeds are to sabotage our agriculture.”

Washington State Department of Agriculture: “That is NOT what the article says. USDA believes this could be a ‘brushing’ scam.”

Petulisa Havili-Wolf: “… disguised biological or chemical attack?”

Washington State Department of Agriculture: “USDA doesn’t have any evidence that it is anything other than a ‘brushing scam.’”

The dialogue reads like a morality play: a lone figure heroically, perhaps forlornly, armed only with logic and patience, holding back the horde. I wanted to know who this person was, so I emailed a public-engagement specialist at the agriculture department.

“That was me,” Karla Salp replied.

Salp explained that she was hired almost six years ago, when the department was preparing to spray an organic pesticide across 10,000 acres, including in Seattle and Tacoma, to combat gypsy moths. She has experience dealing with upset people in delicate situations, she said, and with anti-Asian sentiment (“a lot of the pests have unfortunate names—Asian giant hornet, Japanese beetle, Asian gypsy moth”). She said she tries to respond accurately and positively, and stay out of arguments. Answer by answer it is work that, in its own quiet way, has a certain valiance:

Charles Mitchell: “Is this some kind of agriculture warfare from China? Smart yet scary.”

Washington State Department of Agriculture: “Probably not. Could be a ‘brushing’ scam.”

If I may, a few notes about brushing:

Brushing is illegal in China, but has been around for many years. (Its name seems to derive from the sense of brushing something clean, a linguistic cousin to money laundering.) Companies have developed cat-and-mouse techniques to evade ever more sophisticated detection. In a 2015 academic paper, “E-commerce Reputation Manipulation: The Emergence of Reputation-Escalation-as-a-Service,” researchers provided a snapshot of brushing within China. Over a two-month period, they found evidence of 219,165 fake transactions by more than 11,000 vendors (or “insincere sellers,” the paper’s lovely phrase). Back then, many companies purchased a mail-tracking label without actually sending a package. When physical packages were sent, some were empty or contained only tissues. But in recent years, judging from the many, many online comments I came across from American consumers who appeared to have been brushing recipients, the phony cargo seems to have evolved.

I was fascinated by the bizarre, random scope of what was mentioned—this cascade of gratuitous debris. But I was also struck by how those receiving the items described them. People know what to feel when you take something from them. But when you give them something they don’t want, it’s confusing. You could read their baffled reactions as some kind of free-form poem about consumerism:

“My husband got a package from China that had a pair of white ankle socks for women” … “We received a shoe sole. So strange all these packages” … “two white masks from china that I did not order … I threw them away” … “Got one with a golf ball inside … threw it right away and washed hands” … “a tiny bottle of shampoo” … “a fidget spinner” … “a toy camera, no joke” … “Baby socks. I am old. I don’t have babies nor baby grandchildren” … “I didn’t get seeds but I did get junky, plastic, creepy little cars” … “it sounds funny but it was pretty creepy they were like mini ballerina socks” … “I got mascara, trashed it” … “Sleepy Time TEA … I laughed and said NOT TODAY China” … “a mysterious plastic soap dish from china” … “a travel tooth brush i I didn’t order” … “I came back from a trip a month ago and had 6 small packages waiting for me, each containing one single hair tie” … “I have received random things from China in the past, a marble ! a bead ! and a length of ribbon ! none of which I ordered … I didn’t have anyone to tell about my marble!!! It was blue.”

As the unexpected seed packets kept arriving at homes across the country, American officials from the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and other agencies reached out to their Chinese counterparts. According to the USDA’s El-Lissy, the Chinese authorities were very cooperative: “They emphasized to these companies that this is a prohibited activity and they should stop immediately.” U.S. Customs and Border Protection also upped its efforts to detect and intercept such packages. Meanwhile, the USDA led discussions with Amazon and other e-commerce platforms. Amazon announced in September that plants, plant products, and seeds could no longer be imported into the United States. Its competitor Wish did likewise, citing the “ongoing threat to U.S. consumers.”

Some combination of these efforts was apparently effective. By late last year, the seed packets slowed to a trickle. Problem solved, it seemed, and mystery solved too. Brushing was an explanation that, for all its odd contours, made sense—and just as important, nothing else did. As El-Lissy reaffirmed to me this April, “We are not able to think of other reasons behind this event, aside from the brushing scam, at this time.”

Even so, I felt there was more to know. For instance: Why had the scammers pivoted, sometime in the first half of 2020, to using seeds? Brushing works only if it stays under the radar. As a continuation of an underhanded e-commerce strategy, this choice would seem to be catastrophically counterproductive. (Indeed, I found articles on Chinese websites ruing the attention that these mystery seed packets were attracting, and how they were messing up the business for all involved.) It also seemed implausible that hundreds of different brushing operators had simultaneously hit on this same new strategy. Maybe there was a single enormous operator? When I floated this theory to El-Lissy, he said he couldn’t speculate, and that the USDA was continuing to investigate.

If this was brushing, surely there was somewhere else I could turn to for answers: the companies whose rankings were being manipulated by all this laborious artifice—the e-commerce platforms themselves. If I provided a company with a seed package used for brushing on its platform, it should be able to trace who sent the package, and whether someone had posted an associated review—either of the seeds or of a seemingly unrelated, more expensive item.

I started with the market leader, Amazon. In media reports last summer, Amazon was quoted claiming that it had looked into some of these seed packages and had found that they were genuine Amazon orders delayed by COVID-19. I didn’t take this very seriously. It certainly didn’t tally with what I’d heard, over and over again. While I’d read about some people who had ordered seeds and were subsequently upset because they hadn’t expected them to come from China, or for them to come masquerading as jewelry, many more said they had never ordered the seeds at all. The USDA believes that most, if not all, of its 19,841 packages fit this pattern.

I assumed that Amazon would have come around to this reality, but when I contacted the company in March, I was astonished to hear that its position hadn’t changed: As far as it was concerned, any Amazon packages involved had contained real, delayed orders. I didn’t try very hard to hide how implausible I found this, and my next move seemed obvious. I proposed that I’d supply examples for Amazon to check out, ones I was confident would not match its narrative. My hope was that, once we’d established that people had received seeds they hadn’t ordered, Amazon would work with me to explain further.

None of these mystery packages bore the name or logo of Amazon or any other e-commerce company, but many, I realized, provided a clue: an encrypted phone number on the address label that would turn out to be one of a library of such numbers that Amazon uses to track packages while masking consumers’ contact information. Either these were genuine Amazon packages or someone was taking the trouble to make them seem so.

Lori Culley, the grandmother from Utah who first alerted the American media, seemed the perfect test case. Her two packages carried these telltale Amazon numbers, so with her permission, I sent the company her information.

And that’s when things got really weird.

Culley ordered those seeds herself, Amazon told me. I took this with a grain of salt. Culley had mentioned that she had bought seeds much earlier in the year, and this matched a pattern I’d observed—that many people who received mystery seeds had previously made genuine seed orders. Maybe, I speculated, the brushers thought it made sense to send something that the recipients were used to receiving.

I assumed that Amazon was speciously linking these different events. I asked Culley to go into her order history and pull out her invoices, so we could show that the seeds she knew she had ordered had been delivered long before the mystery seeds arrived.

What she found was not what she—or I—expected.

On April 25, Culley had ordered three packets of seeds from three different sellers: 100 clematis-flower seeds from C-Pioneer for $1.99, 100 clematis-vine seeds from zhang-yubryy for $1.53, and 25 wisteria seeds from DIANHzu1 for $1.99. Unbeknownst to Culley, these sellers were all Chinese, based in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Changsha, respectively. Each seller had more negative reviews than positive ones, many complaining about seeds that were delayed, or hadn’t arrived, or had arrived identified as jewelry. And crucially, Culley’s three April orders, the records showed, had not been shipped until between June 15, 2020, and July 7, 2020.

Further corroboration came when I sent this new information to Terry Freeman, the manager of the seed lab at the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food. She had tentatively identified Culley’s seeds as amaranth and pongam tree. But now, knowing what Culley had ordered, she agreed that the larger seeds—the ones Culley had tried to germinate on her windowsill—were probably wisteria. At least one packet seemed to be exactly what Culley had paid for.

This sent me into something of a tailspin. Initially, I had dismissed Amazon’s explanation, and I had cherry-picked Culley’s experience to prove the company wrong. That had backfired. But surely what Amazon was saying couldn’t be generally true? How could so many people have ordered seeds and then forgotten? And why would so many seed packets start arriving in a sudden surge?

Now I was shocked to realize that I could see exactly how it may have happened.

Consider this scenario:

1. In the early days of shutdowns, when people were spending an unusual amount of time in—and focused on—their homes and gardens, many ordered seeds online. This is clearly true. There were seed shortages, and according to the Home Garden Seed Association, order volumes were eight to 10 times greater than those in the previous year.

2. Many bought seeds from Chinese companies without knowing it. This seems likely enough. Plenty of evidence shows that China-based merchants were selling seeds online. And while e-commerce companies such as Amazon do post details of where vendors are based, the information isn’t obvious or easy to find. Plus, these seeds typically cost less than $3. Few people, I imagine, would suspect that something so cheap could come from so far away.

3. These springtime orders were not delivered; then, in June or July, they were suddenly delivered in great numbers. It seems perfectly plausible that a buildup of orders during China’s extremely strict shutdowns could have led to a large volume of seed packages being sent in the summer, when those shutdowns were substantially lifted.

4. Recipients in America, in the many thousands, didn’t connect the packages they received with orders they had made earlier. This is the hardest part to explain. How could so many people fail to make the association? I can think of a few reasons, many of them mutually reinforcing: the protracted lag time; the disruption of the pandemic; the bewilderment at receiving a package from a country you hadn’t knowingly ordered anything from; the absence of the usual paperwork; seeds that were unidentified and had no planting instructions; the disorienting way the packages were misidentified as jewelry (probably a tactic to get around Customs controls restricting foreign seed sales); and the predisposition, as soon as “unsolicited seeds from China” became a news story, to connect these puzzling packages with that dramatic narrative rather than with a button clicked many months before.

Still, I was uncomfortable with where this logic led. I now had to ask: Could it be possible that during the seeds-from-China fever of 2020, the most delusional theory of all was actually brushing?

I knew it would take only one good counterexample to blow a hole in this forgotten-orders theory, so I continued looking for one. Chris Alwhite seemed like a golden candidate. No one, I was quite sure, forgets ordering 519 seed packets.

This time, after spotting what looked like Amazon numbers on some of the packages, I asked her to go through her order history first. It showed that she had indeed ordered seeds back in May 2020—five times in total. Two orders, from American companies, appear to have shipped quite quickly, but the three she had inadvertently ordered from Chinese sellers (Bravet, Mosichi, and the catchily named PPYPYPYPYPZ) weren’t shipped until many weeks later.

That didn’t come close to explaining the 519 packets. But after I approached Amazon, the situation got only more complicated. The most likely explanation did relate to gifting groups. At least some of the packages were sent to Alwhite as gifts (while the five seed orders she had placed herself were actually sent as gifts to other people). Alwhite’s belief that such packages would always include a barcode or information identifying them as gifts turned out to be mistaken. Why she received quite so many seeds remains bewildering, but given the link between at least some of these seeds and real orders, her case no longer seemed to offer clear indications of brushing.

I moved on to Shayne Duggan, a technical writer for a software company in New Hampshire who’d received seeds on July 20, two days before the first American media story. Her package was labeled “stud earring,” and the return address seemed less a postal coordinate than a clue from some magical-realist fable: “North side of the west gate of South China Avenue, Longgang District, Shenzhen.” Baffled and perturbed, Duggan reached out to a friend who works as a botanist, and he shared the story on botanist bulletin boards. Duggan received more seeds a few days later.

I asked Duggan to check her Amazon order history. And once again, there it was. On April 9, Duggan had ordered 350 Organic Blend Seeds Gourmet Lettuce Unique Tasty Mix, then the following day Garden100 Multicolor Tomato Seeds.

Duggan was somewhat abashed when it all came back to her. “That was, as my kids call it, the OG pandemic, the original pandemic, when we were baking and sewing and doing all that kind of stuff … We weren’t going anywhere; we weren’t seeing anyone; we were hunkered down. That was the mode we were in, and that was the impetus: Oh, maybe I’ll plant some seeds.” When they didn’t come, she forgot all about them, and bought some young lettuces and tomatoes at a plant sale instead. When, months later, the mystery seeds from China arrived, she did momentarily wonder about her previous order, but was too thrown off by the weirdness of the packages to imagine that a sufficient explanation.

These are just three examples, of course. But I’d selected them precisely because I’d thought they were the most likely to establish that brushing may have taken place. It was now clear to me that at least some of these packets were definitely forgotten orders.

It’s not logically impossible for both explanations to be correct: that some packages were brushing and some were delayed orders. But it is hugely improbable. What are the odds that, last summer, two completely different scenarios led to a simultaneous surge in the same weird-looking Chinese seed packages arriving at American homes?

A researcher and I spent a month tracking down more seed recipients, trying to find someone whose experience punctured the forgotten-orders theory. Looking for signs of brushing, we tried to investigate as wide a range of packages as possible whose recipients believed that the seeds had arrived unsolicited. Not every package’s story fit the same pattern. Sometimes the evidence suggested that the seeds had spent months in transit. Sometimes the seeds received didn’t seem to match those that had been ordered. A few didn’t even come from China, but from nearby countries, such as Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. A few appeared to be connected with other e-commerce platforms, though as hard as we looked for these, the lion’s share of what we found was associated with Amazon.

We couldn’t always come to a definitive conclusion. Some of the people we contacted either didn’t have or didn’t want to share the packaging or records required to understand the seeds’ history. But, again and again, people who started out confident about what had happened to them, many of whom were bemused by our requests to search through their old orders, would invariably find something. (Even Sue Westerdale, the “Veg gardening UK” Facebook poster who had first raised the alarm, and who was initially quite dismissive when contacted about this possible narrative, eventually unearthed an April order for “colorful flower meadow seeds,” its shipping date delayed until June.) In fact, in every single case that we were able to research fully, we found a convincing connection between a mystery package and an earlier order.

Despite the evidence, some seed recipients remained skeptical about the scenario we were describing, and they were not the only ones. A month after El-Lissy told me that the USDA was not able to think of any other reasons behind this event apart from brushing, I presented the agency with just such a reason: my forgotten-orders theory. I wanted to know whether the USDA had any direct evidence of brushing, or had verified that anyone had received seeds they had not ordered. The answer was no, with the proviso that the department is involved in an ongoing investigation into the seeds, in tandem with other government agencies, including Customs and Border Protection and the U.S. Postal Service. The USDA spokesperson was not able to share any more details about that investigation, and reminded me that the agency’s focus is on stopping this agricultural threat, not on proving why it happened.

Nevertheless, the USDA clearly remained unconvinced by my arguments. El-Lissy reiterated to me that the agency still thought all the circumstantial evidence pointed to brushing. “We continue to believe it is implausible,” he said, “that thousands of people around the globe ordered seeds and either forgot about them or lied about forgetting them.”

I don’t think that anyone lied. And I certainly don’t rule out there being messier aspects to what happened last summer that remain to be uncovered. Maybe some people will read this story and check their own order history, and new patterns will emerge.

But I believe, on balance, that people probably did forget. Or, to put it another way, that they may have never been fully aware of what they did in the first place. Few of us truly understand the machines and systems at our disposal; we click a button and move on. Meanwhile, tens or hundreds or thousands of miles away, something starts to happen. Steps are taken, wheels are set into motion, decisions—and perhaps mistakes—are made. By the time the distorted ripples of cause and effect make their way back to us, we may no longer recognize that we were the ones who threw a stone into the water.