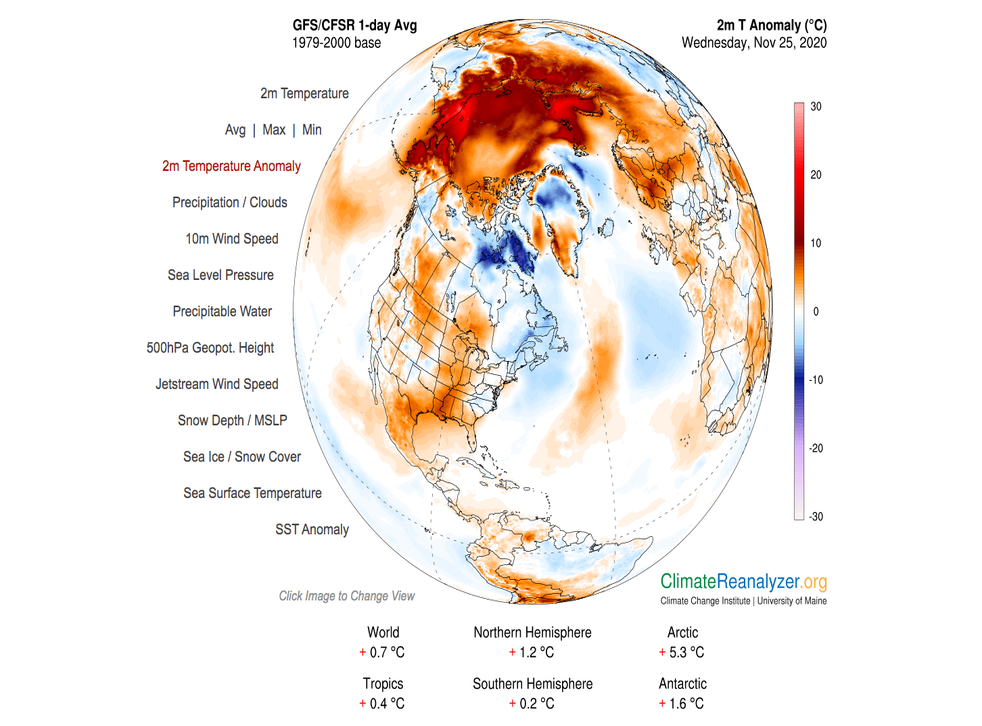

The Arctic’s record-breaking year is continuing as temperatures in late November are reaching up to 12C higher than averages in the 1990s.

The latest figures, from the University of Maine's Climate Reanalayzer, reveal that on 21 November, temperatures were 10-12C higher than normal 30 years ago, while for the entire Arctic, the heat was on average 6.7C higher than normal.

The measurements are the average temperatures for 7.7 million square miles of the Arctic, which has already seen “crazy” high temperatures earlier this year.

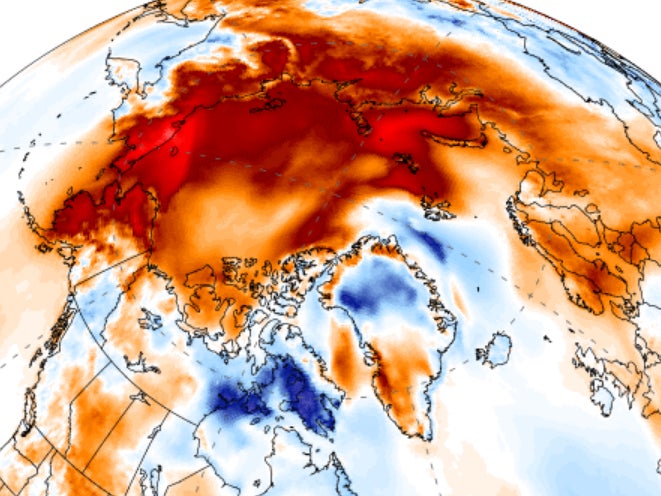

In some warmer pockets - marked on the graphic as bright red areas, show how in recent days temperatures have climbed to more than 20C above averages recorded less than 30 years ago.

While it is still cold by human standards, with temperatures well below zero in many places, the size of the area affected by such an enormous surge in temperatures has alarmed scientists.

“It's all but becoming an annual reminder of the rapid climate change we have observed in the Arctic,” Dr Zack Labe, an Arctic climate specialist from Colorado State University told CBS News.

A belt of warm air is currently stretching from northern Greenland across the North Pole to the Laptev and East Siberian Seas north of the Russian mainland, according to the Barents Observer.

Northeast of Svalbard, over Franz Josef Land and Severnaya Zemlya have also seen similar anomalous heat.

The size of the area affected is almost twice the size of the entire United States.

The unseasonably warm weather comes despite the sun having already set on the Arctic for winter, and follows other record-breaking weather and unusual climate patterns.

The Arctic saw a record low for sea ice coverage in October, and even by mid-November many areas had barely begun to refreeze, leaving vast tracts of open water.

It was the second-lowest Arctic sea ice extent on record, with 2012 the only year when there was less.

As a result, this year the Northeast Passage - a shipping route along the Siberian coast - remained open for a record 112 days, beating the previous record by almost a month.

Historically, the route could open for a handful of days only, though in some years it would not be open at all.

Scientists have warned that as areas of open ocean grow larger, the Sun’s energy is absorbed more, warming the ocean further, amplifying global heating, and inevitably altering the food webs upon which innumerable species depend to survive.

October was the hottest on record for Europe, and came after a record-breaking heatwave in Siberia earlier this year, with the highest temperature ever known inside the Arctic Circle, recorded in June when 38C was recorded in the town of Verkhoyansk.