Photographs by Austin Leong

San Francisco was conquered by the United States in 1846, and two years later, the Americans discovered gold. That’s about when my ancestors came—my German great-great-great-grandfather worked at a butcher shop on Jackson Street. The gold dried up but too many young men with outlandish dreams remained. The little city, prone to earthquakes and fires, kept growing. The Beats came, then the hippies; the moxie and hubris of the place remained.

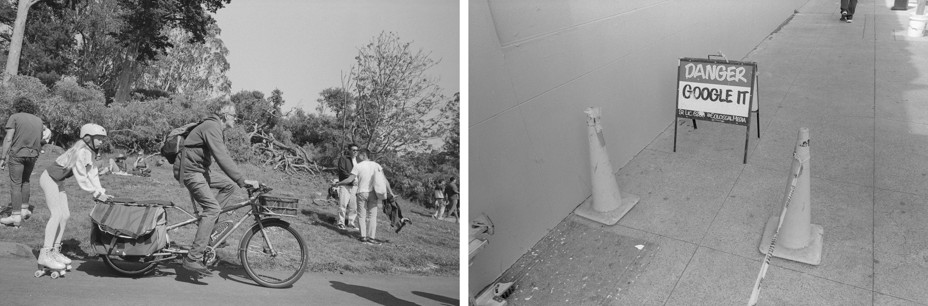

My grandmother’s favorite insult was to call someone dull. I learned young that it was impolite to point when a naked man passed by, groceries in hand. If someone wanted to travel by unicycle or be a white person with dreadlocks or raise a child communally among a group of gays or live on a boat or start a ridiculous-sounding company, that was just fine. Between the bead curtains of my aunt’s house, I learned you had to let your strangeness breathe.

It was always weird, always a bit dangerous. Once, when I was very little, a homeless man grabbed me by the hair, lifting me into the air for a moment before the guy dropped me and my dad yelled. For years I told anyone who would listen that I’d been kidnapped. But every compromise San Francisco demanded was worth it. The hills are so steep that I didn’t learn to ride a bike until high school, but every day I saw the bay, and the cool fog rolling in over the water. When puberty hit, I asked the bus driver to drop me off where the lesbians were, and he did. A passenger shouted that he hoped I’d find a nice girlfriend, and I waved back, smiling, my mouth full of braces and rubber bands.

So much has been written about the beauty and mythology of this city that maybe it’s superfluous to add even a little more to the ledger. If he ever got to heaven, Herb Caen, the town’s beloved old chronicler, once said, he’d look around and say, “It ain’t bad, but it ain’t San Francisco.” The cliffs, the stairs, the cold clean air, the low-slung beauty of the Sunset, the cafés tucked along narrow streets, then Golden Gate Park drawing you down from the middle of the city all the way to the beach. It’s so goddamn whimsical and inspiring and temperate; so full of redwoods and wild parrots and the smell of weed and sourdough, brightly painted homes and backyard chickens, lines for the oyster bar and gorgeous men in chaps at the leather festival. But it’s maddening because the beauty and the mythology—the preciousness, the self-regard—are part of what has almost killed it. And I, now in early middle age, sometimes wish it weren’t so nice at all.

But I do need you to love San Francisco a little bit, like I do a lot, in order to hear the story of how my city fell apart—and how it just might be starting to pull itself back together.

Because yesterday, San Francisco voters decided to turn their district attorney, Chesa Boudin, out of office. They did it because he didn’t seem to care that he was making the citizens of our city miserable in service of an ideology that made sense everywhere but in reality. It’s not just about Boudin, though. There is a sense that, on everything from housing to schools, San Francisco has lost the plot—that progressive leaders here have been LARPing left-wing values instead of working to create a livable city. And many San Franciscans have had enough.

On a cold, sunny day not too long ago, I went to see the city’s new Tenderloin Center for drug addicts on Market Street. It’s downtown, an open-air chain-link enclosure in what used to be a public plaza. On the sidewalks all around it, people are lying on the ground, twitching. There’s a free mobile shower, laundry, and bathroom station emblazoned with the words DIGNITY ON WHEELS. A young man is lying next to it, stoned, his shirt riding up, his face puffy and sunburned. Inside the enclosure, services are doled out: food, medical care, clean syringes, referrals for housing. It’s basically a safe space to shoot up. The city government says it’s trying to help. But from the outside, what it looks like is young people being eased into death on the sidewalk, surrounded by half-eaten boxed lunches.

A couple of years ago, this was an intersection full of tourists and office workers who coexisted, somehow, with the large and ever-present community of the homeless. I’ve walked the corner a thousand times. Now the homeless—and those who care for the homeless—are the only ones left.

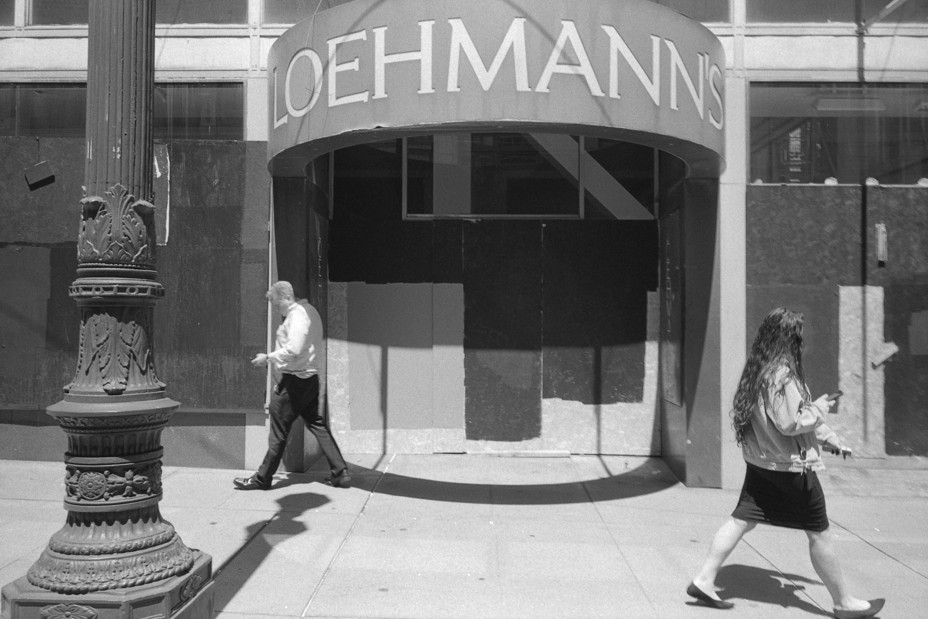

During the first part of the pandemic, San Francisco County lost more than one in 20 residents—myself among them. Signs of the city’s pandemic decline are everywhere—the boarded-up stores, the ghostly downtown, the encampments. But walking these streets awakens me to how bad San Francisco had gotten even before the coronavirus hit—to how much suffering and squalor I’d come to think was normal.

Stepping over people’s bodies, blurring my eyes to not see a dull needle jabbing and jabbing again between toes—it coarsened me. I’d gotten used to the idea that some people just want to live like that. I was even a little defensive of it: Hey, it’s America. It’s your choice.

If these ideas seem facile or perverse, well, they’re not the only ones I’d come to harbor. Before I left, I’d gotten used to the idea of housing so expensive that it would, as if by some natural law, force couples out of town as soon as they had a kid. San Francisco now has the fewest children per capita of any large American city, and a $117,400 salary counts as low-income for a family of four.

[Annie Lowrey: Four years among the NIMBYs]

I’d gotten used to the crime, rarely violent but often brazen; to leaving the car empty and the doors unlocked so thieves would at least quit breaking my windows. A lot of people leave notes on the glass stating some variation of Nothing’s in the car. Don't smash the windows. One time someone smashed our windows just to steal a scarf. Once, when I was walking and a guy tore my jacket off my back and sprinted away with it, I didn’t even shout for help. I was embarrassed—what was I, a tourist? Living in a failing city does weird things to you. The normal thing to do then was to yell, to try to get help—even, dare I say it, from a police officer—but this felt somehow lame and maybe racist.

A couple of years ago, one of my friends saw a man staggering down the street, bleeding. She recognized him as someone who regularly slept outside in the neighborhood, and called 911. Paramedics and police arrived and began treating him, but members of a homeless advocacy group noticed and intervened. They told the man that he didn’t have to get into the ambulance, that he had the right to refuse treatment. So that’s what he did. The paramedics left; the activists left. The man sat on the sidewalk alone, still bleeding. A few months later, he died about a block away.

It was easier to ignore this kind of suffering amid the throngs of workers and tourists. And you could always avert your gaze and look at the beautiful city around you. But in lockdown the beauty became obscene. The city couldn’t get kids back into the classroom; so many people were living on the streets; petty crime was rampant. I used to tell myself that San Francisco’s politics were wacky but the city was trying—really trying—to be good. But the reality is that with the smartest minds and so much money and the very best of intentions, San Francisco became a cruel city. It became so dogmatically progressive that maintaining the purity of the politics required accepting—or at least ignoring—devastating results.

But this dogmatism may be buckling under pressure from reality. Earlier this year, in a landslide, San Francisco voters recalled the head of the school board and two of her most progressive colleagues. These are the people who also turned out Boudin; early results showed that about 60 percent of voters chose to recall him.

[Read: Why California wants to recall its most progressive prosecutors]

Residents had hoped Boudin would reform the criminal-justice system and treat low-level offenders more humanely. Instead, critics argued that his policies victimized victims, allowed criminals to go free to reoffend, and did nothing to help the city’s most vulnerable. To understand just how noteworthy Boudin’s defenestration is, please keep in mind that San Francisco has only a tiny number of Republicans. This fight is about leftists versus liberals. It’s about idealists who think a perfect world is within reach—it’ll only take a little more time, a little more commitment, a little more funding, forever—and those who are fed up.

If you’re going to die on the street, San Francisco is not a bad place to do it. The fog keeps things temperate. There’s nowhere in the world with more beautiful views. City workers and volunteers bring you food and blankets, needles and tents. Doctors come to see how the fentanyl is progressing, and to make sure the rest of you is all right as you go.

In February 2021, at a corner in the lovely Japantown neighborhood, just a few feet from a house that would soon sell for $4.8 million, a 37-year-old homeless man named Dustin Walker died by the side of the road. His body lay there for at least 11 hours. He wore blue shorts and even in death clutched his backpack.

I can’t stop thinking about how long he lay there, dead, on that corner, and how normal this was in our putatively gentle city. San Franciscans are careful to use language that centers people’s humanity—you don’t say “a homeless person”; you say “someone experiencing homelessness”—and yet we live in a city where many of those people die on the sidewalk.

Here is a list of some of the organizations that work with the city to fight overdoses and to generally make life more pleasant for the people on the street: Street Crisis Response Team, EMS-6, Street Overdose Response Team, San Francisco Homeless Outreach Team, Street Medicine and Shelter Health, DPH Mobile Crisis Team, Street Wellness Response Team, and Compassionate Alternative Response Team. The city also funds thousands of shelter beds and many walk-in clinics.

The budget to tackle homelessness and provide supportive housing has been growing exponentially for years. In 2021, the city announced that it would pour more than $1 billion into the issue over the next two years. But almost 8,000 people remain on the streets.

Alison Hawkes, a spokesperson for the Department of Public Health, said money spent on the well-being of the homeless goes to good use: Many people “end up remaining on the street but in a better situation. Their immediate needs are taken care of.”

But many are clearly in an awful situation. San Francisco saw 92 drug deaths in 2015. There were about 700 in 2020. By way of comparison, that year, 261 San Franciscans died of COVID.

[Read: ‘I don’t know that I would even call it meth anymore’]

Of course, you can’t blame the plague of meth and opioids on my hometown. Fentanyl is a national catastrophe. But people addicted to drugs come from all over the country in part for the services San Francisco provides. In addition to the supervised drug-use facility in the plaza, San Francisco has a specially sanctioned and city-maintained slum a block from City Hall, where food, medical care, and counseling are free, and every tent costs taxpayers roughly $60,000 a year. People addicted to fentanyl come, too, because buying and doing drugs here is so easy. In 2014, Proposition 47, a state law, downgraded drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor, and one that Boudin said he wouldn’t devote resources to prosecuting.

This approach to drug use and homelessness is distinctly San Franciscan, blending empathy-driven progressivism with California libertarianism. The roots of this belief system reach back to the ’60s, when hippies filled the streets with tents and weed. The city has always had a soft spot for vagabonds, and an admirable focus on care over punishment. Policy makers and residents largely embraced the exciting idea that people should be able to do whatever they want to do, including live in tent cities and have fun with drugs and make their own medical decisions, even if they are out of their mind sometimes. But then fentanyl arrived, and more and more people started dying in those tents. When the pandemic began, the drug crisis got worse.

In 2019, someone posted a picture in a Facebook group called B.A.R.T. Rants & Raves, where people complain about the state of the regional transportation system. The photo was of a young man, slumped over on a train. People were chiming in about how gross the city was.

A woman named Jacqui Berlinn wrote in the comments, simply: “That’s my son.”

His name is Corey Sylvester and he’s 31 years old. She posted a photo of him when he was sober: “May he return there soon.”

Berlinn has five children, and is also raising Sylvester’s daughter. Since she posted that comment, she’s become an activist, calling on the city to crack down on drug sales, put dealers in jail, and arrest her son so he’s forced to become sober in jail, which she sees as the only way to save his life. She told me that she feels San Francisco has failed people like him: “Nothing that is being done is improving the situation.” Her work is nonpartisan, she said, but “I’d be lying if I didn’t say I really want to see Boudin recalled.”

Not long ago, we met on a stoop by the Civic Center, where her son used to hang out. She hadn’t seen him in months, but she spoke with him periodically. She cried as she talked about his journey into drugs. She said he was a heroin addict. He’d get sober after stints in jail, but it wouldn’t last. “I’d see him sometimes, and he didn’t look that bad, and that was how it was for 10 years,” she told me. “But then the dealers started putting fentanyl in everything, and being on fentanyl, it’s changed him, deteriorated him so rapidly … Before, he looked pretty healthy and smiling. And now he’s got this stoop. He walks almost at a 40-degree angle, like an old man.”

He’s been stabbed twice. He got an infection in his thumb, and she thought he might lose the hand. “They need to stop ignoring the fact that there are people out here selling fentanyl on the streets,” she said. “When it was just heroin—I can’t believe I’m saying ‘just heroin.’ Fentanyl is different. We’re normalizing people dying.”

One day, Berlinn was out looking for Corey in the Tenderloin neighborhood when she came across someone else’s son. “He was naked in front of Safeway … And he was saying he was God and he was eating a cardboard box.”

She called the police. Officers arrived but said there was nothing they could do; he said he didn’t want help, and he wasn’t hurting anyone. “They said it’s not illegal to be naked; people are in the Castro naked all the time … They just left him naked eating cardboard on the street in front of Safeway.”

What happened to the man at the Safeway, what happened to Dustin Walker—these are parables of a sort of progressive-libertarian nihilism, of the belief that any intervention that has to be imposed on a vulnerable person is so fundamentally flawed and problematic that the best thing to do is nothing at all. Anyone offended by the sight of the suffering is just judging someone who’s having a mental-health episode, and any liberal who argues that the state can and should take control of someone in the throes of drugs and psychosis is basically a Republican. If and when the vulnerable person dies, that was his choice, and in San Francisco we congratulate ourselves on being very accepting of that choice.

Last year, I bought my wife her wedding ring at a beautiful little antique store a few blocks from my childhood home. It was ransacked at the end of December. The shaken owner posted a video; the showcases were empty and the whole place was covered in glass.

You can spend days debating San Francisco crime statistics and their meaning, and many people do. It has relatively low rates of violent crime, and when compared with similarly sized cities, one of the lowest rates of homicide. But what the city has become notorious for are crimes like shoplifting and car break-ins, and there the data show that the reputation is earned. Burglaries are up more than 40 percent since 2019. Car break-ins have declined lately, but San Francisco still suffers more car break-ins—and far more property theft overall—per capita than cities like Atlanta and Los Angeles.

The head of CVS Health’s organized-crime division has called San Francisco “one of the epicenters of organized retail crime.” Thefts in San Francisco’s Walgreens are four times the national average. Stores are reducing hours or shutting down. Seven Walgreens closed between last November and February, and some point to theft as the reason. The city is doing strikingly little about it. About 70 percent of shoplifting cases in San Francisco ended in an arrest in 2011. In 2021, only 15 percent did.

[Annie Lowrey: The people vs. Chesa Boudin]

The movement to decriminalize shoplifting in San Francisco began in 2014 with Proposition 47, the state law that downgraded drug possession and also recategorized the theft of merchandise worth less than $950 as a misdemeanor. It accelerated in 2019 with the election of Boudin as district attorney.

It is difficult to remember now, but the Boudin election was thrilling for the city. It occurred during the heights of rage against President Donald Trump, when more and more people were becoming aware of police violence against Black people and demanding criminal-justice reforms. London Breed, the city’s first Black female mayor, wanted a liberal moderate for D.A., but Boudin ran to the left as a fierce progressive ideologue whose worldview was shaped by his imprisoned parents, members of the Weather Underground. He was a public defender, not a prosecutor at all. He had worked in Venezuela and in 2009 congratulated the former dictator Hugo Chávez for abolishing term limits. Boudin was a charismatic figure. His campaign manager called him “a national movement candidate.”

The Police Officers Association fought hard against him, spending $400,000 on a barrage of attack ads, according to the San Francisco Examiner. They didn’t work. At Boudin’s election party, a city supervisor led the crowd in a chant of “Fuck the POA.” During his campaign, Boudin said he wouldn’t prosecute quality-of-life crimes. He wanted to “break the cycle of recidivism” by addressing the social causes of crime—poverty, addiction, mental-health issues. Boudin was selling revolution, and San Francisco was ready. In theory.

But not in fact. Because it turns out that people on the left also own property, and generally believe stores should be paid for the goods they sell.

It has become no big deal to see someone stealing in San Francisco. Videos of crimes in process go viral fairly often. One from last year shows a group of people fleeing a Neiman Marcus with goods in broad daylight. Others show people grabbing what they can from drugstores and walking out. When a theft happens in a Walgreens or a CVS, there’s no big chase. The cashiers are blasé about it. Aisle after aisle of deodorant and shampoo are under lock and key. Press a button for the attendant to get your dish soap.

The rage against Boudin was related to that locked-up soap, but it went far beyond it.

Under Boudin, prosecutors in the city could no longer use the fact that someone had been convicted of a crime in the past to ask for a longer sentence, except in “extraordinary circumstances.” Boudin ended cash bail and limited the use of gang enhancements, which allow harsher sentences for gang-related felonies. In most cases he prohibited prosecutors from seeking charges when drugs and guns were found during minor traffic stops. “We will not charge cases determined to be a racist pretextual stop that leads to recovery of contraband,” Rachel Marshall, the district attorney’s director of communications, told me.

Boudin is a big proponent of “collaborative courts” that focus on rehabilitation over jail time, such as Veterans Justice Court and Behavioral Health Court, and under his tenure they tried more cases than ever before. In 2018, less than 40 percent of petty-theft cases were sent to these programs, compared with more than 70 percent last year. Marshall said it was the judges who decided which cases to divert, not Boudin, and eligibility rules for the collaborative courts have loosened in recent years. But critics also pointed out that Boudin got fewer convictions overall: 40 percent in 2021, compared with about 60 percent under his predecessor.

About 60 prosecutors had left since Boudin took office—close to half of his team. Some retired or were fired, but others quit in protest. I talked with two who joined the recall campaign. One of them, a homicide prosecutor named Brooke Jenkins, told me she left in part because Boudin was pressuring some lawyers to prosecute major crimes as lesser offenses. (Marshall said this was “a lie.”) She couldn’t be part of it. “The victims feel hopeless,” Jenkins told me. “They feel he has lost their opportunity for justice. Right now what they see and feel is that his only concern is the criminal offender.” (I wouldn’t be surprised to see Jenkins run for D.A. herself, though this isn’t something she’s floated yet.)

A 2020 tweet from the Tenderloin police station captured the frustration of the rank and file: “Tonight, for the fifteenth (15th) time in 18 months, and the 3rd time in 20 days, we are booking the same suspect at county jail for felony motor vehicle theft.”

Boudin has a rugged jawline and fast, tight answers for his critics. His office vehemently rejected the argument that he wasn’t doing enough to tackle crime. “The DA has filed charges in about 80 percent of felony drug sales and possession for sales cases presented to our office by police,” Marshall pointed out. After all, he could prosecute people only if the police arrested them, and arrest rates had plummeted under his tenure. So how could that be his fault? But why had arrest rates plummeted? The pandemic was one reason. But maybe it was also because the D.A. said from the beginning that he would not prioritize the prosecution of lower-level offenses. Police officers generally don’t arrest people they know the D.A. won’t charge.

In 2020, I interviewed Boudin while working on a story for The New York Times. When we talked about why he wasn’t interested in prosecuting quality-of-life crimes, he explained that street crime is small potatoes compared with the high-level stuff he wants to focus on. (“Kilos, not crumbs” is a favorite line.) He has suggested that many drug dealers in San Francisco are themselves vulnerable and in need of protection. “A significant percentage of people selling drugs in San Francisco—perhaps as many as half—are here from Honduras,” he said in a 2020 virtual town hall. “We need to be mindful about the impact our interventions have … Some of these young men have been trafficked here under pain of death. Some of them have had family members in Honduras who have been or will be harmed if they don’t continue to pay off the traffickers.”

[Read: His dad got a chance at clemency. Then his baby was born.]

Of course there is good in what Boudin was trying to do. No one wants people incarcerated for unfair lengths of time. No one wants immigrants’ relatives to be killed by MS-13. Few of Boudin’s policy ideas—individually, and sometimes with reasonable limitations—are indefensible. (Ending cash bail for truly minor offenses, for instance, protects people from losing their job and more while in jail.) But as with homelessness, the city’s overall take on criminal-justice reform moved well past the point of common sense. Last month a man who had been convicted of 15 burglary and theft-related felonies from 2002 to 2019 was rearrested on 16 new counts of burglary and theft; most of those charges were dismissed and he was released on probation. It really didn’t inspire confidence that the city was taking any of this seriously.

Boudin’s defenders liked to dismiss his critics as whiny tech bros or rich right-wingers. One pro-Boudin flyer said Stop the right-wing agenda. But the drumbeat of complaints came from plenty of good liberals, and so did the votes against him. If it were only the rich, well, the rich can hire private security, or move to the suburbs. And many do. They’re not the only people who live here, and they’re not the only ones who got angry.

It may not have been so clear until now, but San Franciscans have been losing patience with the city’s leadership for a long time. Nothing did more to alienate them over the years than how the progressive leaders managed the city’s housing crisis.

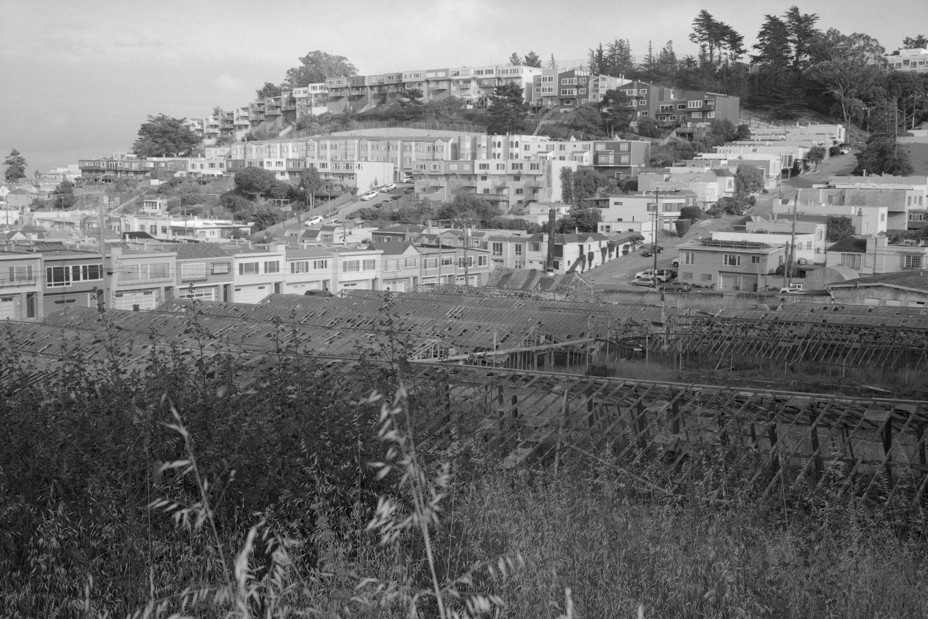

Consider the story of the flower farm at 770 Woolsey Street. It slopes down 2.2 acres in the sunny southern end of the city and is filled with run-down greenhouses, the glass long shattered—a chaos of birds and wild roses. For five years, advocates fought a developer who was trying to put 63 units on that bucolic space. They wanted to sell flowers there and grow vegetables for the neighborhood—a kind of banjo-and-beehives utopian fantasy. The thing they didn’t want—at least not there, not on that pretty hill—was a big housing development. Who wants to argue against them? In San Francisco the word developer is basically a slur, close to calling someone a Republican. What kind of monster wants to bulldoze wild roses?

Decades of progressive governance in San Francisco yielded a thicket of regulations—safety reviews, environmental reviews, historical reviews, sunlight-obstruction reviews—that empower residents to essentially paralyze development. It costs only $682 to file for a discretionary review that can hold up a construction project for years, and if you’re an established club that’s been around for at least two years, it’s free. Plans for one 19-unit-development geared toward the middle class were halted this year because, among other issues raised by the neighbors, the building would have increased overall shadow coverage on Dolores Park by 0.001 percent.

The cost of real estate hit crisis levels in the 2010s, as ambitious grads from all over the world crammed into the hills to work in the booming tech industry. Soon, there was nowhere for them to live. Tech workers moved into RVs, parked alongside the poor and unhoused. Illegal dorms sprang up. Well-paid young people gentrified almost every neighborhood in town. In 2018, when London Breed was elected mayor at the age of 43, she had only just stopped living with a roommate; she couldn’t afford to live alone.

Existing homeowners, meanwhile, got very, very rich. If all other tactics fail, neighbors who oppose a big construction project can just put it on the ballot. If given a choice, who would ever vote to risk their property value going down, or say “Yes, I’m fine with a shadow over my backyard”? It doesn’t happen.

Rage against this pleasant status quo has come from a faction of young renters. I once went to a training session in the Mission District run by a pro-housing group called YIMBY—for “Yes in My Backyard.” I watched a PowerPoint presentation (“And here’s another reason to be mad at your grandparents! Next slide.”) and then joined the group for drinks.

“The elderly NIMBYs literally hiss at people,” said Steven Buss, who now runs a moderate organizing team called GrowSF, about the tension at community housing meetings. (One foggy night, at one of those meetings, I heard the hissing, and it was funny, and the project they were talking about never got built.)

Gabe Zitrin, a lawyer, popped in: “Like 770 Woolsey. I love kale too, but you could house 50 kids and their families on that site. It’s about priorities. They want a farm. They’re selfish and they’re vain. A farm does not serve the common good. I can’t tell them not to want it—but I can tell them that housing is what we need more. I don’t want to end up surrounded by a bunch of super-rich people and a farm.”

The city’s progressives seem to feel that it is all just too beautiful and fragile to change. Any change will mean diminishment; any new, bigger building means the old, charming one is gone, and the old, charming resident is probably gone too. The flow of newcomers is out of control; they should just stop coming here. The community gardens have to stay, along with the sunlight spilling across the low buildings. No one thinks about it as damning teachers and firefighters to mega-commutes. No one thinks of it as kicking out the middle class. Given the choice between housing people in sidewalk tents or in new buildings that might risk blocking an inch of their view of the bay, San Franciscans, for years, chose the tents.

The anger directed at Chesa Boudin probably could have been contained. The petty crime was frustrating, but it wasn’t what lit the city up for revolution. The housing crush is miserable, but it’s been that way for more than a decade now. The spark that lit this all on fire was the school board. And the population ready to rage was San Francisco’s parents.

The city’s schools were shut for most of the 2020–21 academic year—longer than schools in most other cities, and much longer than San Francisco’s private schools. In the middle of the pandemic, with no real reopening plan in sight, school-board meetings became major events, with audiences on Zoom of more than 1,000. The board didn’t have unilateral power to reopen schools even if it wanted to—that depended on negotiations between the district, the city, and the teachers’ union—but many parents were appalled to find that the board members didn’t even seem to want to talk much about getting kids back into classrooms. They didn’t want to talk about learning loss or issues with attendance and functionality. It seemed they couldn’t be bothered with topics like ventilation. Instead they wanted to talk about white supremacy.

One night in 2021, the meeting lasted seven hours, one of which was devoted to making sure a man named Seth Brenzel stayed off the parent committee.

Brenzel is a music teacher, and at the time he and his husband had a child in public school. Eight seats on the committee were open, and Brenzel was unanimously recommended by the other committee members. But there was a problem: Brenzel is white.

“My name’s Mari,” one attendee said. “I’m an openly queer parent of color that uses they/them pronouns.” They noted that the parent committee was already too white (out of 10 sitting members, three were white). This was “really, really problematic,” they said. “I bet there are parents that we can find that are of color and that also are queer … QTPOC voices need to be led first before white queer voices.”

Someone else called in, identifying herself as Cindy. She was calling to defend Brenzel, and she was crying. “He is a gay father of a mixed-race family,” she said.

A woman named Brandee came on the call: “I’m a white parent and have some intersectionality within my family. My son has several disabilities. And I really wouldn’t dream of putting my name forward for this.” She had some choice words for Cindy: “When white people share these kinds of tears at board meetings”—she pauses, laughing—“I have an excellent book suggestion for you. It’s called White Tears/Brown Scars. I’d encourage you to read it, thank you.”

Allison Collins, a member of the school board, dealt the death blow: “As a mixed-race person myself, I find it really offensive when folks say that somebody’s a parent of somebody who’s a person of color, as, like, a signifier that they’re qualified to represent that community.”

Brenzel remained mostly expressionless throughout the meeting. He did not say a word. Eventually the board agreed to defer the vote. He was never approved.

The other big debate on these Zoom calls was whether to rename schools named for figures such as Abraham Lincoln and Dianne Feinstein, the first female mayor of San Francisco. The board labeled these figures symbols of a racist past, and ultimately voted to rename 44 “injustice-linked” schools—though after a backlash, the board suspended the implementation of the changes.

The board members were arguably doing what they had been put there to do. Collins and her two most progressive colleagues were elected in 2018, the year before Boudin, and it was a headier time, when Trump’s shadow seemed to loom over even the smallest local office. Collins had a blog focused on justice in education, and there was a sense that she would champion a radical new politics. But during the endless lockdown, enthusiasm began to wane, even among many people who’d voted for her. They found themselves turned off by the board’s combative tone—as well as by its actual ideas about education.

In February 2021, board members agreed that they would avoid the phrase learning loss to describe what was happening to kids locked out of their classrooms. Instead they would use the words learning change. Schools being shut just meant students were “having different learning experiences than the ones we currently measure,” Gabriela López, a member of the board at the time, said. “They are learning more about their families and their cultures.” Framing this as some kind of “deficit” was wrong, the board argued.

That same month, the board voted to replace the rigorous test that screened applicants for Lowell, San Francisco’s most competitive high school, with a lottery system. López had explained it this way: “Grades and standardized test scores are automatic barriers for students outside of white and Asian communities.” She said they “have shown to be one of the most effective racist policies, considering they’re used to attempt to measure aptitude and intelligence. So the fact that Lowell uses this merit-based system as a step in applying is inherently racist.”

Collins echoed that: “‘Merit’ is an inherently racist construct designed and centered on white supremacist framing.”

If you didn’t like these changes, tough. A parent on Twitter accused López of trying to destroy the school system, and she replied with the words “I mean this sincerely” followed by a middle-finger emoji. In July, on the topic of the declining quality of life in San Francisco, she wrote, “I’m like, then leave.”

Gabriela López must have thought that history was on her side. Boudin, too. But things are turning out differently. If there was a tipping point in this story, it was when the city’s Asian American parents in particular got really, really mad.

As Allison Collins’s profile rose during the pandemic, critics started looking through her old tweets. There were bad ones. In 2016, she had written: “Many Asian Americans believe they benefit from the ‘model minority’ BS. In fact many Asian American teachers, students and parents actively promote these myths. They use white supremacist thinking to assimilate and ‘get ahead.’”

She also complained about Asian Americans not speaking out enough about Trump: “Do they think they won’t be deported? Profiled? Beaten? Being a house n****r is still being a n****r. You’re still considered ‘the help.’”

The San Francisco Bay Area is 52 percent white, 6.7 percent Black, and 23.3 percent Asian. And many Asian San Franciscans were horrified by the tweets.

“Her comments deeply insulted my family and the entire Chinese community in San Francisco,” Kit Lam told me. Lam is an immigrant from Hong Kong with two children in public school. He works for the school district, in the enrollment department, though he just learned that his job will be eliminated next month. He said he knew what richer parents were doing during the pandemic because he saw the paperwork: They were pulling their kids out and sending them to private schools. Lam didn’t have that choice.

In April 2021, he started going on 1400 AM, the Bay Area’s Chinese-language radio station, to express his outrage. He spoke out against school closures and the decision to get rid of the admissions test for Lowell. Asian students have traditionally been overrepresented at Lowell; getting in is one of the best ways for high-achieving poor and middle-class kids in San Francisco to rise up the economic ladder.

Many people from his community agreed with him. They began gathering signatures and raising money for a campaign to recall Collins, López, and another progressive board member, Faauuga Moliga. Siva Raj, one of the recall organizers, told me that roughly half of those volunteering for the campaign spoke Chinese.

After the tweets came to light, a member of the board asked Collins to voluntarily step down. But she refused. Instead, she sued five of her fellow members. She also sued the district. She asked for $87 million, citing, among other afflictions, “severe mental, and emotional distress,” “damage to self-image,” and “injury to spiritual solace.”

Her case was tossed. And in February 2022, San Franciscans voted decisively to remove all three from the board. A landslide 76 percent voted to recall Collins, and the other two were recalled by about 70 percent each. They have been replaced by moderates, appointed by the mayor. Collins and López slammed their opponents as agents of white supremacy, but the turnout was diverse, and impressive, especially for a special election: More people voted to recall the board members than had cast votes for them in the first place.

Boudin’s opponents, likewise, came from all over the city. He liked to say they were funded by elites, and the recall campaign did raise about twice as much money. But wealthy people have donated to the pro-Boudin campaign, too. The racial group that was most likely to say they wanted Boudin recalled? Asian Americans. Their allies included many from the remnants of the city’s middle class, as well as the same sort of swayable liberals who went from voting for Collins to recalling her.

Now a number of groups are trying to address quality-of-life issues in the city. There is the new California Peace Coalition, which opposes the open-air drug markets, and includes parents of drug users who are at risk of or have died from overdose. There’s Innovate Public Schools and Stop Crime SF, which are self-explanatory. Shine On SF is “reigniting civic pride” by cleaning up the city’s streets. SF.Citi is advocating for the interests of tech workers.

For a long time, says Michelle Tandler, a start-up founder who documented downtown’s collapse on Twitter, “San Francisco progressives and Democrats were so focused on Trump that they weren’t paying attention.” Suddenly, they’re paying attention.

And Mayor Breed is responding. She was elected during the Trump administration, like Boudin and the school board, and her approval numbers are also faltering. But she’s in a different mold. Breed is a canny politician who knows which way the wind is blowing, and is open to changing course depending on the results.

Just a few years ago, she had proudly embraced the “defund the police” movement; no longer. This spring, after the city’s gay-pride parade banned police officers from marching in uniform, Breed announced that out of solidarity, she wouldn’t march either.

I took a stroll with her back in February. She had just given a press conference on anti-Asian hate crimes outside a senior center in Chinatown. As in places like New York, the city had seen a spike in the reporting of hate crimes against Asians. People were scared. Breed grew up in the city’s projects and knows residents who have had family members shot and killed recently. “I know a lot of people who supported Chesa because there was a strong push for criminal justice,” she told me. “I don’t think people believed that it meant that justice would not occur.” She added, “That’s not justice reform, if everyone who commits the crime is getting off for the crime.” Now she’ll have a chance to replace him.

As we talked, we walked through Chinatown, then up past the $7 million homes of Russian Hill and down into North Beach. The bay lay ahead; the cable-car drivers waved to the mayor; the city’s problems seemed far off. But Breed was angry, disappointed with the progressive faction and how it had let the city down. A few months earlier, Breed had announced a new approach to crime, starting with the Tenderloin, whose streets and sidewalks are full of fentanyl’s chaos. She declared it to be in a state of emergency and approved three months of funding for increased law enforcement there.

The order was mostly symbolic—the drug problem isn’t limited to a few bad blocks. Often a sweep of the homeless just means pushing the tents and dealers down the road. And anyone who lives in San Francisco knows the Tenderloin has been an emergency for years. But it allowed the mayor to trot out some new rhetoric: “What I’m proposing today and what I will be proposing in the future will make a lot of people uncomfortable, and I don’t care.” It was time, she said, to be “less tolerant of all the bullshit that has destroyed our city.”

My hometown isn’t turning red on any electoral maps. But the shift is real. The farm at 770 Woolsey? The developer finally has approval to turn it into housing. If progressives have overplayed their hand, gotten a little decadent in culture-war wins and stirring slogans, without the good government to back them all up, San Francisco is showing the way toward an internal reformation.

Before the school-board vote, the last local recall in San Francisco was in 1983. There has not been this level of conflict at farmers’ markets, where dueling signature-gatherers face off across from the organic-dog-treat kiosk, in almost 40 years. This is, in part, because until recently many San Franciscans were afraid. If a tech worker complained, they were reviled. If an aging hippie complained, they were a racist old nut. It was easier to blame all of our issues on outsiders—those Silicon Valley interlopers who came in and ruined the city. The drugs, the homelessness, the crime—blame the Google employees who skewed the city’s condo market and brought in their artisanal chocolates, their scooters, their trendy barbers. If not for them and the inequality they created, San Francisco would still be good.

There’s some truth to that: You cannot tell the story of the housing crunch without the tech boom. But people started looking at City Hall, and at the school board. They realized there were no tech bros there. The fentanyl epidemic and the pandemic cracked something. With the city locked down endlessly, with people dying in the streets, with schools closed, it was slowly becoming okay to say Maybe this is ridiculous. Maybe this isn’t working.

Of course, it’ll take more than a couple of recall votes to save San Francisco. When I asked Breed about the new center for addicts in the plaza—the creation of which she supported—she seemed a little uncomfortable and soon after wanted to wrap up our interview. She said something vague about how not all change can happen at once.

NIMBYism and fentanyl are as much a part of the San Francisco landscape now as the bridge and the fog. And the school board is still school-boarding. At the end of May, it announced that the district would no longer use the word chief in any job titles, out of respect for Native Americans (despite the fact that the word actually comes from the French chef).

The other day I walked by Millennium Tower. Once a symbol of the push to transform our funky town into a big city, it’s a gleaming 58-story skyscraper in the heart of San Francisco, and it’s been sinking into the ground—more than a foot since it was finished in 2009. A group of men in hard hats was just standing there, staring up at it. The metaphor is obvious, but San Francisco has never been a subtle city. I’d like to believe those guys finally had a plan to fix the tower. At least they seemed to accept that it needed fixing.

For so long, San Francisco has been too self-satisfied to address the slow rot in every one of its institutions. But nothing’s given me more hope than the rage and the recalls. “San Franciscans feel ashamed,” Michelle Tandler told me. “I think for the first time people are like, ‘Wait, what is a progressive? … Am I responsible? Is this my fault?’”

San Franciscans are now saying: We can want a fairer justice system and also want to keep our car windows from getting smashed. And: It’s not white supremacy to hope that the schools stay open, that teachers teach children, and, yes, that they test to see what those kids have learned.

San Franciscans tricked themselves into believing that progressive politics required blocking new construction and shunning the immigrants who came to town to code. We tricked ourselves into thinking psychosis and addiction on the sidewalk were just part of the city’s diversity, even as the homelessness and the housing prices drove out the city’s actual diversity. Now residents are coming to their senses. The recalls mean there’s a limit to how far we will let the decay of this great city go. And thank God.

Because Herb Caen was right. It’s still the most beautiful city you’ll ever see.