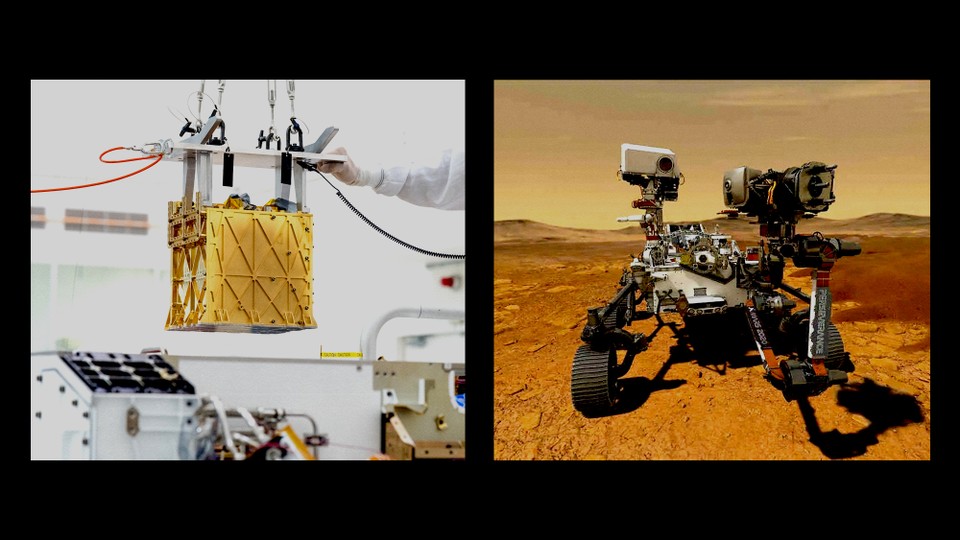

Millions of miles away on Mars, in a barren crater just north of the equator, a rover is wandering around, carrying a gold-coated gadget the size of a toaster. The machine inhales the Martian air and strips away contaminants. It splits the atmospheric gas into constituent parts, takes what it needs, and then reassembles that blend to create something that is in very short supply on Mars: oxygen. Real, breathable oxygen, the kind you took in as you read these sentences.

After a bit of analysis, the machine puffs out the oxygen, harmlessly releasing the molecules into the Martian environment. The act makes this very sophisticated toaster, situated in the belly of NASA’s Perseverance rover, the closest thing to a small tree on Mars.

And according to the researchers behind the little machine, it’s a pretty good tree. Every time they’ve run it, the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment—MOXIE, for short—has successfully converted Martian air, which is almost entirely made of carbon dioxide, into oxygen gas. “We’re not far from being able to produce oxygen at the rate that would sustain a human being,” Michael Hecht, a planetary scientist at MIT’s Haystack Observatory who leads the project, told me. “A small dog would be just fine at the rate that we produce.”

[Read: What would a dog do on Mars?]

MOXIE is a clever chemistry experiment. It is also a remarkable event in the history of space exploration. If human beings want to build a long-term home on Mars, they’ll have to make use of the planet’s natural resources instead of lugging everything they need all the way from Earth. “We have to be able to live off the land,” Jennifer Heldmann, a NASA scientist who works in this futuristic field—known as in situ resource utilization—told me. “This is the first time that we’ve been able to test and demonstrate the technology to do that.”

And oxygen is wonderfully versatile. Not only would it sustain humans on a planet that their lungs weren’t designed for, but it could also be combined with other compounds to produce rocket fuel so that they could return to Earth. On Mars, we’re the aliens. We’d need to invent all kinds of stuff to give future astronauts a chance to survive there, let alone live comfortably. It is almost sci-fi-ish to think about, but by tinkering with Mars’s atmosphere, we—as in humankind—have managed to figure out at least one piece of that endeavor.

The MOXIE experiment whirred into action in February of last year, after Perseverance touched down and started working toward its prime mission: collecting rocky samples that could contain the tiny imprints of long-dead Martian life. MOXIE had its own work cut out for it. The Martian atmosphere is so thin that, compared with our own, it’s almost a vacuum. “I like to say we’re making oxygen out of thin air,” Hecht said. “If you were a Martian, you would think that those of us on Earth are fish swimming around in a thick soup of atmosphere.”

[Read: We’ve never seen Mars quite like this]

Mars also experiences far more dramatic shifts in its atmospheric conditions. Daytime and nighttime temperatures can vary by about 212 degrees Fahrenheit (100 degrees Celsius). The air shifts as well, thinning out during the warm days and becoming denser during the cold nights. Swings in air pressure occur seasonally, too. During Martian winters, some of the atmosphere condenses into frost and settles over the poles, reducing the air pressure across the rest of the planet. During Martian summers, air pressure ticks up. All of these factors influence the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere—MOXIE’s main snack.

To see how MOXIE would fare, engineers powered up the instrument during different times of day and different seasons. They found that “the most difficult time to collect carbon dioxide is in the middle of the day, in the middle of the winter, when it’s both warm and the pressure is low,” Hecht said. “And the easiest time is the middle of the night in the middle of the summer, when the pressure is high and the temperature is low.” But during every run, the machine worked, spending an hour churning out oxygen.

The team has yet to deploy MOXIE during dawn or dusk, though, when “the density of the air is changing, and the temperature is changing rapidly,” Hecht said. Engineers are concerned that the sudden shift in the presence of carbon dioxide could damage the instrument as it draws the gas in. Hecht says they’ll do some testing with a lab version of MOXIE on Earth first, but they’re confident that they can get their little lunch box to work under these conditions, too.

[Read: Mars’s soundscape is strangely beautiful]

Other groups of scientists are thinking about how to make oxygen factories for future Mars missions; one team recently devised a method for generating oxygen from carbon dioxide with the help of plasma. And other researchers are thinking deeply about how to use additional resources on Mars, such as the ice deposits just below the planet’s surface. Future astronauts could mine the frozen water and purify it for everyday use. They could also steal the water’s hydrogen molecules and put them toward the work of getting home. “You can make methane, which is a rocket propellant,” Julie Kleinhenz, a NASA research engineer who studies in situ resource utilization and is not involved with the MOXIE project, told me. “You could fully refuel an ascent vehicle with methane and oxygen just by using resources on Mars, through processes that are pretty well understood.” Some basic items, such as spacesuits and toilets, will have to come over from here. But if you can make something on Mars, you can reduce the heavy baggage that makes it more difficult to blast off from Earth.

The team behind MOXIE imagines a future in which a scaled-up version, capable of doing the work of hundreds of trees, hums away on the surface of Mars, working around the clock. The factory would be launched ahead of a human mission, so that there would be plenty of oxygen reserves by the time astronauts arrive. That future is still many years away; NASA says the earliest that it could land astronauts on the red planet is sometime in the early 2040s. Elon Musk wants to go much earlier than that with SpaceX, but even the space billionaire will face the same constraints that would make a Mars trip difficult (funding, physics, the cosmic radiation between here and there). A mega-size MOXIE would be just one item on a very long packing list. But MOXIE has a certain concreteness to it that feels thrilling even now. It is the kind of detail that makes a human base on Mars seem a tiny bit more realistic. Imagine, decades from now, an engineer sitting at a console, inhaling air derived from an alien atmosphere, and telling one of her staff: “Hey, Steve, we’re getting some weird MOXIE readings—can you go check it out?”