Photographs by Whitten Sabbatini

MEMPHIS, Tenn.—You’ll hear a few different stories about why they call Mary Wainwright’s North Memphis neighborhood “Smokey City,” but she says it’s because the old shotgun houses all had woodstoves and little chimney pipes that pumped smoke into the sky. Wainwright would know—she grew up in Smokey City, where her family moved from East Tennessee before she was born, and she’s lived there for many of her 62 years. When she was a child, a massive Firestone tire plant bordered the neighborhood, and the smell of rubber was also the smell of prosperity: Thousands of people had good jobs with good pay there and at other nearby factories.

The Firestone smokestack still looms over the little neighborhood, but now it’s surrounded by acres of empty concrete pads where the factory stood before it closed almost 40 years ago. Some shotgun houses remain, though many are on their last legs. As the population has dropped, the culture has changed, Wainwright says. She remembers when everyone left their doors unlocked at night and kids ran freely through yards, knowing that any adult would watch out for—or, if necessary, scold—them.

Wainwright is the kind of person you’d want as a neighbor: She’s quick with a joke, blunt and no-nonsense, and ready to help out. When the coronavirus pandemic struck, she canvassed the neighborhood handing out masks. When vaccines first became available, she knew that many of her neighbors didn’t have computers or internet access to make appointments, so she convinced officials to set up a pop-up clinic at her church. The line stretched around the block.

Even so, you might not want to live near her in Smokey City these days. Crime and violent-crime rates in the area and its next-door neighbor Klondike are routinely two to three times as high as in Memphis overall, according to statistics gathered by Whole Child Strategies, a nonprofit that works in the neighborhood. The homicide rate is four to five times as high.

When Wainwright got a new car not long ago, her son begged her to get something other than the Infinitis she’s long preferred—drug dealers like them too much and she might get carjacked, he warned. Wainwright has seen two people killed on her street. “One was laying up under my car. The other one, he got shot, ran around the church,” she recalls.

Wainwright’s sister, who lives nearby in the house they grew up in, is paralyzed on one side, but she doesn’t want to leave the neighborhood where she’s always lived, and her disability checks won’t cover much else anyway. “She spends 40 percent of her time on the floor, because of guns, shooting, just every day. During daylight hours,” Wainwright says. “That’s how bad it is in the neighborhood. You know, it is what it is. We live from day to day, and we pray at night, pray all day, pray in the morning when we get up, that we can survive the neighborhood.”

To Wainwright, the causes of the crime aren’t hard to identify—there are no good jobs, nuclear families have decayed, and drugs are rampant—and neither are the perpetrators. She says she knows who the local gang members are, and so do the police. She can drive through the neighborhood and point out the drug houses and the spots where she’s seen shootings in broad daylight. She’s happy to show them to a visitor, just as she has pointed them out to city officials. Once, while touring the neighborhood with her, a top aide to the mayor was solicited for anything he wanted at one notorious spot. “I mean a-ny-thing you want,” she cackles. (Wainwright doesn’t flinch from describing the violence, but she also doesn’t go more than a couple sentences at a time without a joke or a garrulous laugh.)

Police raided that house where the aide was solicited the next day, she recalls, but they’ve been less effective at keeping a lid on crime more broadly in the area. In fact, they’ve been less effective across the city. Memphis set a record for murders in 2021, with 346—breaking the previous record of 332, set in 2020. According to FBI data, Memphis was the most violent metropolitan area in the United States in 2020.

In early September, a jogger’s abduction and murder made national headlines. A few days later, four people were killed and three others injured in a shooting spree that stretched over a full day. The city has long had troubled pockets, but those areas are getting worse, and crime is spilling over into historically safer neighborhoods. When I visited last fall, residents were tittering about a murder in the upscale Harbor Town area. Last November, the up-and-coming rapper Young Dolph was shot and killed at a bakery in Memphis, drawing national attention to the rising murder rate.

No role of the police is more basic than keeping people from being killed or seriously injured, and the Memphis police seem unable to do that. Wainwright’s son, an aircraft mechanic in Little Rock, talks about moving his family back home to Memphis, but she’s tried to persuade him to stay put: She’s just too worried about losing him to violent crime.

Two years ago, at a time of historically low crime rates and unprecedented anger about police brutality, reforms to law enforcement felt possible, maybe even imminent. Peace was not evenly distributed—places like Memphis were still more violent than some other big cities—but the trends were in the right direction, and across generations and races, Americans were upset about bad policing. Now the country has entered a grim period, as violent crime has risen nationwide. The effect is that both higher crime rates and failed policing seem locked in place.

Across the nation, police-reform efforts have stalled. Minneapolis voters resoundingly rejected a plan, developed after George Floyd’s murder, to replace the police with a new Department of Public Safety. Several cities that announced high-profile plans to reduce police budgets have since restored and even increased funding. In New York, voters elected Eric Adams, a former NYPD captain and staunch defender of law enforcement, as mayor. In San Francisco, the “progressive prosecutor” Chesa Boudin was recalled in June. And in Congress, bipartisan momentum for national reforms have come to nothing. The backlash hasn’t happened everywhere, but President Joe Biden seemed to reflect the gathering consensus when he said during his State of the Union address in March, “We should all agree the answer is not to defund the police. It’s to fund the police. Fund them. Fund them. Fund them with the resources and training—resources and training they need to protect our communities.”

One common way to frame the tension in Memphis and other cities like it is to say that Black communities are sometimes forced to choose between over-policing—aggressive law enforcement that keeps crime down but also infringes on civil liberties and sweeps too many people into the criminal-justice system for petty offenses not enforced in tonier neighborhoods—and under-policing, where the streets are largely ceded to criminals. In much of Memphis, however, the choice doesn’t seem to exist. Residents get both.

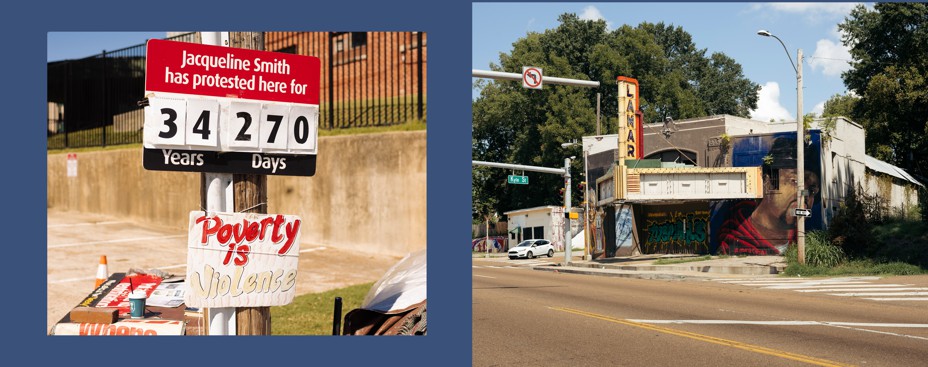

Judging by statistics, Memphis might sound bleak and blighted, but that’s not how it feels. The city is a checkerboard of manicured mock Tudors and crumbling craftsmans, but the shabbier neighborhoods are often more inviting than tourist traps like Beale Street. Murals of the local icons Isaac Hayes and B. B. King adorn the sides of boarded-up buildings, and rich smoke and the smell of ribs pour from barbecue joints. The challenges facing Memphis are similar to those in other major cities, but more dramatic. It struggles with education, income inequality, racial disparities, and crime. But many of these gaps are intensified by the fact that among major American cities, only Detroit has a higher poverty rate and a higher percentage of the population that is Black.

When I asked Josh Spickler, who leads the nonprofit Just City Memphis, about justice in the city, he replied, “There’s not a lot of it, and it’s hard to find.” This has been true for the roughly two centuries of the city’s existence. The future Ku Klux Klan grand wizard Nathan Bedford Forrest lived and traded slaves in Memphis before the Civil War. In 1892, the lynching of three Black men was front-page news in The New York Times. During the 1960s and ’70s, the police department spied extensively on activists, including Martin Luther King Jr., whom cops did a better job of surveilling than protecting: An officer assigned to keep an eye on him left two hours before he was assassinated. In 1978, the surveillance operation was finally shut down under a consent decree.

More recently, the Memphis Police Department has wrestled with the sorts of police controversies familiar in most American towns and cities. In 2015, an officer shot and killed 19-year-old Darrius Stewart, setting off protests and demands for a smaller department; more focus on violent crime and less on minor offenses; and economic programs that would help keep Memphians away from crime and the justice system. In a climactic 2016 protest, marchers blocked traffic on Interstate 40 over the iconic Hernando de Soto Bridge. Yet just as demonstrations around the country after Floyd’s murder were cresting, violent crime began to rise around the country, including in Memphis.

The city of Memphis is heavily Democratic, but it’s not especially liberal compared to other major cities. The city’s Black electorate seems to mirror a nationwide division: Older generations tend to be more conservative on criminal justice, while younger generations are a bit more convinced that police are the problem. A 2021 poll for the Memphis Shelby Crime Commission found that Black voters in Shelby County were roughly split on their local police, with 51 percent giving a good rating and 47 percent a poor one, a substantial drop from 2020, with younger voters among the most skeptical. But the idea that Memphis, or the Black community nationally, is cleanly divided on police is false.

Wainwright thanks God for the police and invites them to warm up and take a break in her church, where she works part-time. But at the same time, she’s frustrated that she can get pulled over for going 10 over the speed limit but well-known gang members can walk down the street in Smokey City unbothered by cops. “They know, and won’t mess with ’em.” And just as she worries about criminals harming her son, she worries the police could kill him, too.

Across town, Keedran Franklin, a high-profile organizer, has surprisingly similar mixed feelings. I ran into him cooking up sirloin-and-aioli sandwiches in his food truck, parked at the picket line outside a Kellogg’s factory. Franklin has the prominent cheekbones, piercing eyes, and infectious laugh of Chris Rock, and some of the same manic energy. His career began in a local violence-interruption group that tried to reach at-risk members of the community. But after he came to suspect that authorities were using the group’s rolls to track or arrest participants, Franklin became an outspoken critic of law enforcement.

His descriptions of local intrigue can sound paranoid, but as the old joke goes, being paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you. In 2018, a federal judge ruled that the Memphis police had violated the 1978 consent order, after an officer acknowledged surveilling several activists, including Franklin, as well as a longtime columnist for the Memphis Commercial Appeal. (Among the methods were fake social-media profiles. Replying to a suspicious query, the officer wrote, “block me if you want, but i’m not a cop.” He was, in fact, a cop.) I started to understand why, when I contacted Franklin via Facebook, he refused to talk to me unless I came to see him at the truck.

Franklin and his allies don’t dismiss the violence that exists in Memphis. What they disagree about is the solution. And while his politics are far to the left of the average Memphian, Franklin’s critique of the police is fairly mainstream: He sees a department that has gotten its priorities wrong so often that it’s not able to solve the problems in front of it.

As backlash to “defunding the police” has grown, a series of polls has demonstrated that, while some Black Americans—especially younger ones—are strongly opposed to the police per se, most hold a more positive view, even if they also support some reforms. A 2021 poll from the leftist outfit Data for Progress found that 80 percent of Black respondents said police are more likely to use force on Black people, and when asked whether police could be trusted, nearly two-thirds (63 percent) agreed that “you can’t be too careful.” But about two-thirds of Black respondents also said that regular police patrols in their neighborhood would make them feel safer.

These questions take elevated levels of crime as a given—not everyone has to contemplate the optimal level of patrols. “Point me to the ideal neighborhood in any community in the country, or any suburban community,” says the Reverend Earle Fisher, a veteran Memphis activist. “Guess what you don’t see? Any police officers.”

The city’s mayor, Jim Strickland, became the first white mayor in 24 years when he won the 2015 election with a plurality of the vote, while two Black candidates split the rest of it. A promise to be tough on crime was crucial to his defeating the incumbent mayor in 2015, and he reprised the talking point four years later, when he won handily. “Memphis is at a critical juncture,” he said during his first election. “Violent crime is up and jobs are down.” He promised to hire more police officers if elected.

Amid the 2020 protests, Strickland announced a plan called “Reimagining Policing,” which included gathering feedback from the community. The complaints the city received closely echoed those made by activists: targeting of Black men, and different treatment of people of color in general; over-the-top use of force and arrests; arrogance and verbal abuse of citizens, and the way officers tended to respond furiously to perceived disrespect; and pervasive fear of the Memphis Police Department among Black residents. Yet as part of Reimagining Policing, the city also boasted that the department already followed many elements of “8 Can’t Wait,” a national campaign for agencies to enact eight minimum standards, such as banning chokeholds and shooting at moving cars. That says a lot more about 8 Can’t Wait than it does about the MPD, though. If the department is already meeting the benchmarks but still eliciting such a negative reaction from the community, it is clearly not doing enough.

To Fisher, the result was an example of the regular cycle of civil-rights protests in Memphis: “The aggressive advocacy by people on the ground is ultimately marginalized and demonized by people in the administration, only to have a watered-down version of it implemented later on.”

By the time the final Reimagining Policing report landed in summer 2021, it was already obsolete. The city was in the midst of what would become the second straight record year for murders. Strickland had returned to his old tough-on-crime rhetoric, having appointed Joy Touliatos, a longtime political ally who had been clerk of the local juvenile court, to lead a group-violence intervention project. What exactly Touliatos did is unclear; she and the city declined my interview requests, and in September 2021, she was quietly transferred to the city’s public-works department. (When I asked a spokesperson about the move, she was surprised that I was even aware of it, and did not offer any comment.) The head of the MPD, Mike Rallings, retired in spring 2021. To replace him, the city hired C. J. Davis, the former police chief of Durham, North Carolina. Davis named recruiting and retaining officers as a top priority.

Davis and Strickland want to hire more police officers, and citizens seem to agree: The Memphis Shelby Crime Commission found in a 2020 poll that roughly eight in 10 Memphians support adding police to the force. In fact, that’s been Strickland’s idea all along, but the odds of it happening are low. Memphis has a smaller police department now than when Strickland took office, and police departments around the country are struggling to recruit and retain good officers—a task that’s harder in a department under a consent decree in a city with high rates of violent crime and relatively low pay.

Even with a smaller force than its leaders would like, Memphis will spend 38 percent of its 2023 budget, almost $276 million, on policing and public safety. That’s among the highest rates for cities of its size. (By a different metric, spending on police per resident, Memphis rates are closer to the middle among big cities.) For example, Atlanta will spend 32 percent of its annual budget on policing in 2023, Louisville 24 percent, and Nashville roughly 20 percent. All three of those cities also saw significantly less violent crime and fewer murders per 100,000 residents in 2020 than Memphis, while deploying fewer officers relative to population. Some cities spend more: Charlotte, for example, has allocated more than 40 percent of its 2023 budget to policing, but also saw around a third of Memphis’s murder and violent-crime rates.

These examples show that with careful strategy and spending, cities can achieve reductions in crime. In particular, studies have found that “hot-spot” policing—concentrating officers in particular areas—can drive crime down, at least in those immediate areas and sometimes more broadly. A recent study found that increases in the size of a big-city police department are correlated with declining homicide rates, though the effect in southern cities with large Black populations, like Memphis, might be smaller. The downside is that larger police forces tend to also make larger numbers of petty arrests. In a separate study, scholars found that “the size of a city’s police budget and the size of its police force both strongly predicted how many arrests its officers made for things like loitering, trespassing, and drug possession.” In practice, that means more Black men moving through the criminal-justice system.

Somehow, Memphis seems to be getting only the worse ends of this trade-off. I heard again and again that police spend too much time making minor arrests while leaving serious criminals to wreak havoc. Meanwhile, murder rates and violent crime have climbed since Strickland took office. In 2015, when he was elected, there were 21 murders per 100,000 residents. In 2016, that number climbed to 30, settled to between 28 and 29 for three years, and then spiked again to 44 in 2020. (Major property crime is down over the same period.) When police solve more murder cases, murder rates tend to go down—but murder clearance rates in Memphis have sunk.

One big chunk of the police budget, around $10 million over a decade, has gone to a surveillance system called SkyCop. The city installed more than 2,000 cameras mounted on poles around the city. As you drive around Memphis, the little police-blue lights of the system twinkle seemingly everywhere, giving the impression—depending on your inclination—of either safety or life in a police state, complete with a name from a dystopian novel. A 2021 investigation by the Daily Memphian found that the answer is probably neither: Violent crime has increased since SkyCop’s introduction, and the cameras haven’t played much of a role in solving crimes.

It isn’t fair to blame Strickland or the MPD for the jump in murders over the past two years, since nearly every city in the country has experienced something similar. But it is reasonable to ask why the steps that didn’t succeed in driving down murders between 2015 and 2019, when the rate in other major cities was falling, would work any better for Memphis now. I tried to get an answer to this question, and to get someone to defend the strategy to me. This proved more difficult than I had expected.

Ahead of my visit, I repeatedly asked the mayor’s office to talk about policing and crime, but his spokesperson declined to make him available or answer questions. So did Joy Touliatos, the former gun-violence czar. The city wouldn’t make her successor available, either. C. J. Davis and the police department wouldn’t talk either. The union representing officers referred me to the department. I also repeatedly contacted the Memphis Shelby Crime Commission, an unusual nonprofit organization that’s led by a former county prosecutor and is an influential voice in setting local policy, but the commission never replied. I contacted Strickland’s office when I traveled to Memphis and got a quick phone call promising more soon, but never got a response to repeated further requests. In short, not a single one of these officials was willing to defend the city’s crime-fighting strategy—on or off the record.

What is remarkable is that despite the poor results, the police department seems politically unassailable. One leader who was willing to speak with me was JB Smiley Jr., a young member of the Memphis City Council. Smiley is smart and energetic, and he speaks the language of police reform fluently. “I don’t think you can police your way out of crime,” he told me. “I’m of the opinion that if you do the same thing over and over, you’re probably going to get the same results.”

Smiley said that Memphians complained that police were set apart from the community, and he cast the decisive vote on the council to preserve a policy requiring that Memphis police officers live within the city limits. (In 2022, state legislators overturned the requirement.)

Yet Smiley will only go so far in criticizing the police department—in part because of his sense of how his constituents feel about the issue. “Folks in my district, they’re going to tell you, they want their law-enforcement officers,” he said. “I don’t think we need to take money from our police budget. I don’t think you’ll hear any of our elected officials say that.”

Smiley paused, then added something I kept hearing: “You might hear Tami Sawyer say that.”

If you’d met Sawyer as a child, you wouldn’t be surprised that she is in politics today, but you might be surprised by the politics she espouses. Sawyer grew up in an upper-middle-class family whose views she describes as moderate to progressive. She remembers writing a letter to President George H. W. Bush about homelessness as a small girl; she was the high-school class president, and served as vice president of the state model United Nations. By 2012, she was living in Washington, D.C., working for a government contractor at the Navy Yard. She was on a path to a comfortable, stable career.

But after the 2013 shooting at the Navy Yard, she moved back to Memphis and started to become involved in activism. When Officer Darren Wilson wasn’t charged in the death of Michael Brown, protests broke out in cities around the country, and Sawyer looked for demonstrations to join in Memphis. There weren’t many, so she started organizing them. Activism, in turn, organized her beliefs. “When I got involved in the movement, I wasn’t well versed in very many, like, liberal-progressive issues,” she told me. “The movement taught me Black Lives Matter, taught me about wage equity.”

Sawyer was deeply involved in the outside game, working closely with other activists. She led a die-in at the Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, and pushed for the removal of a statue of Forrest, the Klan leader and Confederate general. But she started looking at electoral politics, too. In 2016, she unsuccessfully ran for the Tennessee House of Representatives. Two years later, she was elected to the Shelby County Commission. In 2019, she ran against Strickland for mayor but finished a distant third.

Last year, Sawyer announced that she wouldn’t run for reelection to the commission. Several years of high-profile activism, harassment by neo-Confederates, and the grind of her post have convinced her that elected office isn’t a sustainable way for her to push change. Sawyer doesn’t hesitate to criticize Strickland (sometimes in salty terms), but she is also a student of rhetoric, literally: She finished a master’s degree on the topic this spring. This means that even when she’s arguing for defunding the police, she doesn’t necessarily use that language. “You know, when I talk to my own parents, I don’t say ‘defund the police.’ If I don’t say ‘defund the police,’ we’re on the same page!”

What’s written on that page is an argument that what ails Memphis is not crime itself. The high levels of crime the city is experiencing now are instead symptoms of underlying causes: failing education systems and a lack of employment opportunities. The avenues to stable, well-paying jobs have disappeared, moving out of town when factories like the Firestone plant in Smokey City closed. Now students graduate from high school, or drop out, and have few legitimate opportunities outside of low-paying jobs at companies like FedEx, by far the largest employer in the city.

“The issue is not that people are committing crime. The issue is that people who are poor people are disconnected from resources,” Sawyer said. “These kids watch rich people on TV all the time, and you want them to throw boxes at FedEx. That’s like the crust of their opportunity here.”

Leaders in Memphis widely agree that better education and economic development are needed. But where would the money to pay for them come from? The state government is dominated by Republicans, who are more interested in conservative projects that city leaders oppose—like a 2021 state “constitutional carry” law, which allows people to bear guns without a permit, which leaders say makes it harder to police violence in the city—than in the kind of major spending such a change would require, especially on a heavily Black and Democratic city. The city has few levers to raise its own revenue, especially since poverty is high and wealthier residents might just decamp to nearby lower-tax jurisdictions (if they haven’t already done so). In the interim, the city might treat stabilizing crime as a way to try to lead economic development. But that would require actually stabilizing crime, something the police haven’t shown the ability to do.

This summer, I called Wainwright to see how things were going in Smokey City since my visit. She was feeling upbeat: She’d just finished renovating her house with help from a local development agency, and she was working on bringing a grocery store back to the neighborhood—the last one closed years ago—and perhaps starting a community garden. But when the conversation turned to crime, her tone changed. Shootings remain common around the neighborhood, she said, to the point that deacons at her church arm themselves.

She was unimpressed by Davis’s first months on the job, expressing her disapproval with every southern woman’s favorite double-edged benediction: “The police chief, bless her heart, she can’t do nothing with this city. She don’t know nothing about it. That’s one of the things that messes a city up. When you bring in people, it’s going to take them three to four years to learn what’s going on in that operation.”

Three or four years is a tiny span in the life of a city, and hardly any time for a leader to learn not just the ins and outs of an organization as complex as a municipal police force, but also the particular histories and politics of the city’s neighborhoods or the stories that make up residents’ lives. Yet three or four years can be a huge span in the life of an individual or a family—time to get married or have a child or move or see a loved one killed. In three or four years, Memphis’s citizens will still be fighting over crime and how to address it. But based on recent history, that period will also see hundreds of Memphians die by violence, and thousands more of them assaulted with a gun. A crisis can just keep on persisting.