Here is the foundational narrative on which I was raised: In March 1933, my great-uncle Arthur Kahn walked out of his apartment in Würzburg, Germany, for what was supposed to be a short Easter-break trip to see relatives. He was 21, training to be a doctor. He didn’t know it, but his name had been placed on a list of students suspected of Communist ties. He had none, but he was arrested in Nuremberg. A few weeks later, he was transferred to Dachau, which had just opened as a prison. Adolf Hitler had been in power for 10 weeks. Within 24 hours of his arrival, Arthur was killed—believed to be the first shot among a group of four Jewish men and the Holocaust’s first Jewish victim.

I learned about Arthur from the elder of his two surviving brothers—Herbert Kahn, the man I called Opa. Arthur died on Passover; at the time, Opa was 12. During the second seder, when I was a child, the whole table would seem to brace itself for his palpable despair. I liked it better when Opa would sidle up and tell me stories. Arthur was a meticulous draftsman. He was a state chess champion. He had hoped to be a cancer researcher, just as the field was first developing.

Opa died three months before I graduated from college. It was a shock to realize that I was now older than Arthur had ever been. That summer, I tracked down the New York Times article that announced the Dachau murders. Its headline parrots the Nazi lie: “Nazis Shoot Down Fleeing Prisoners.” I read Timothy W. Ryback’s book Hitler’s First Victims, a meticulous account not just of the killings themselves, but of the prosecutor who tried to indict the men responsible for them at tremendous personal risk. He hadn’t believed the official explanation. He couldn’t overlook the obvious—four victims, all Jewish. The Nazis suppressed the case. The killers went free.

I became obsessed. I wanted to know where the police found Arthur in Nuremberg—had he known he was doomed? And then: Did he like music? Did he write in diaries? Did he have a favorite book? I wrote to archivists and historians, searching for answers with a determination that bordered on compulsion. I struggled to explain what I hoped to find. Closure wasn’t the right word. I felt too embarrassed to write closeness. Scholars invited me to tour their institutions. I scoured footnotes, submitting files concerning Arthur’s fate to a translator so that I could read them. I took notes on the names of his torturers. I ransacked libraries. I filed research requests. I read about how he bled.

Between 2018 and 2021, I traveled to Germany—to the sites of Arthur’s life and death—four times. I felt drawn to these places, as if walking in his footsteps might tell me something about the person whose gruesome death had come to define his life. I needed to make present the person I had known as an absence. I wanted to see him.

Not long after the Axis powers surrendered, the Allies turned their attention to the business of commemoration. Across Germany, liberators tacked up posters showing stacks of Jewish corpses. Concentration camps such as Majdanek and Auschwitz and Dachau were secured and preserved. It was a practical choice. The land would be evidence in imminent war-crime trials. God had confronted Cain; the Allies heard the blood-soaked ground too. It was also the moral position. The camps would become three-dimensional keepers of the historical record—geographical testimonies of the incontrovertible horror of the Holocaust.

Over time, concentration camps throughout Europe were restored and opened to the public. So were several Nazi headquarters and the estate in bucolic Wannsee where Nazi officials had feasted and drank together, plotting the “Final Solution.”

The public reckoning was slower. Germans still cast themselves as the war’s true victims. Had the violence not devastated them too? Some concentration camps fell into disrepair, warding off potential visitors. In Dachau, the first memorial commemorating the Jewish genocide wasn’t built until 1960. It was a Catholic chapel. The camps—like Buchenwald—that stood on East German land were better-maintained, but with an ulterior motive. The German Democratic Republic framed the war as a struggle between German fascists and Marxism. The extermination of the Jewish people was an afterthought.

[Read: The other history of the Holocaust]

But memorialization soon became a fixation on both sides of the Atlantic. A record number of German citizens tuned in to watch the melodramatic but affecting miniseries Holocaust in 1979. In 1980, Congress established the United States Holocaust Memorial Council, which set about planning the development of a Holocaust museum in Washington, D.C., as well as an annual national event to remember the devastation. One event begat two and then 10 and then thousands. In 1990, a writer for The New York Times took stock of Holocaust-memorial projects. The 1988 index she consulted listed “19 museums, 48 resource centers, 34 archives, 12 memorials, 25 research institutes, and five libraries.” We remembered with a kind of desperation, as a bulwark.

I was born in 1992, part of Generation “Never Forget.” I was a toddler when the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum opened its doors next to the National Mall. I read The Number on My Grandfather’s Arm in kindergarten. I read Number the Stars in middle school. When, at age 11, I learned that a friend had zero grandparents who were Holocaust survivors, it was a revelation. How alien, I thought. How American.

“Never forget” was a promise we kept with ourselves and expected the world to keep, too. I believed in it like a vow I had taken. When I said it, I didn’t hear the other, more vulnerable note. The one that sounded like a plea.

I went to a Jewish preschool, Jewish summer camp, then Jewish grade school and high school. Normal children in normal households have parents and grandparents who attend their school recitals and clap when the curtain falls. The people I knew had parents and grandparents who attended our school recitals and, when the curtain fell, whispered, “Hitler didn’t win.” We were the real and durable survival—the triumph he’d wanted to wipe out. Even when we were little, we knew our stories. Our murdered great-grandparents, great-uncles, and great-aunts. The first cousins our parents never met. We knew whose grandfathers had been married before, had had first wives and first children murdered in the camps. I knew Arthur’s historical distinction: the first. Over time, I collected a few more details about him—his brilliance, his good looks, his various romances.

But of course, most of what I knew concerned that terrible week in April—the sequence of murder and heartbreak and burial. I knew Arthur’s father, Levi, had paid to have his son’s coffin released from Dachau. I knew it had arrived sealed shut. When did I learn the particulars? I don’t remember ever being told them. We inherited these stories as we inherited our hair colors, the shape of our faces. The Nazis ruled that Arthur had been killed in an attempted escape, gunned down while he tried to flee. But I had been told—had I ever not known?—that Levi pried open the coffin. He saw that his son had been shot through the forehead. Levi and his wife, Martha, and their two surviving sons didn’t leave for America until August 1939, two weeks before the war broke out. Arthur’s death was supposed to be a freak act of violence, not an omen.

I arrived in Berlin for the first time in October 2018. I had been invited to visit German and Norwegian prisons with a mixed group of elected officials, advocates, wardens, and one other writer. I wanted to get a feel for the area and learn what I could about the first concentration camps, Dachau included. In Berlin, prison staffers explained the strict laws that governed the treatment of incarcerated people. The German constitution—adopted in 1949 and written to safeguard democratic processes in the aftermath of the war—declares that “human dignity shall be inviolable.” In 1977, as a new generation began to grapple with the Holocaust, the Prison Act was passed, reversing an earlier legal principle holding that incarcerated people were not entitled to basic civic rights. The law established “resocialization”—as opposed to punishment or protection of the public—as the purpose of prison. These laws—a kind of “Never forget” infrastructure—informed not just the nation’s approach to restorative justice, but the architecture of its penitentiaries. In the prisons I visited, rooms had bathrooms, with doors that closed. Incarcerated people cooked their own meals in communal kitchens. We toured a courthouse that had been operational since 1906 to observe a sentencing, but I kept losing focus. I was sitting in a German courthouse that had been operational since 1906.

For my second trip, in the late spring of 2019, I spent a week in Berlin on a fellowship. Researchers delivered lectures about the nation’s slide into fascism. We visited the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In the bookstore, I found a doorstop of a book documenting the rise of Nazi concentration camps. I checked the index—“Kahn, Arthur, page 55.” The book details how SS guards took over for state police, empowered to kill. After a nauseating description of the hours of torture that Arthur endured before his execution, it notes that Heinrich Himmler, the future mastermind of the Final Solution and the architect of the SS, held a press conference announcing the four Dachau murders.

In New York, I retrieved files of photocopied letters that Opa had sent historians, correcting the record about Arthur. He’d tracked down each mistaken mention of his brother in various histories of the Holocaust and organized his correspondence in order. In some cases scholars had confused the timing of Arthur’s death. Opa chafed in particular at the books and articles that reinforced the Nazi claim that Arthur had been a political radical. In another folder, I found the letter that he sent in 1943 to the president of the Agudath Israel Youth Council, who’d had a part in helping him secure safe transport to America. Once the United States entered the war, both Opa and his brother had enlisted in the Army. When he wrote the letter, he was still in basic training in Alabama.“I would not mind to be sent over to Europe,” he told the man in a new, unfamiliar language. “There is nothing I would rather do than fighting Hitlerism.”

From Fort McClellan, he recounted his travails as an observant Jew, including his struggle to find kosher food on base. He wrote about how he tried to squeeze ritual in when he could, sometimes reciting the morning service while he marched. He studied Jewish texts when he should have been sleeping. “I manage to learn a bit,” he wrote, “and so never forget that I am a Jew.”

In September 2019, I went back. This time, I retraced Arthur’s steps as best I could. I orchestrated stops in Würzburg, where Arthur studied; Nuremberg, where he had been arrested and later buried; Dachau, where he was killed; and Frankfurt and Munich, where I scheduled interviews and requested boxes of files from the state archives. I would end in Gemünden am Main, where the Kahn children had grown up.

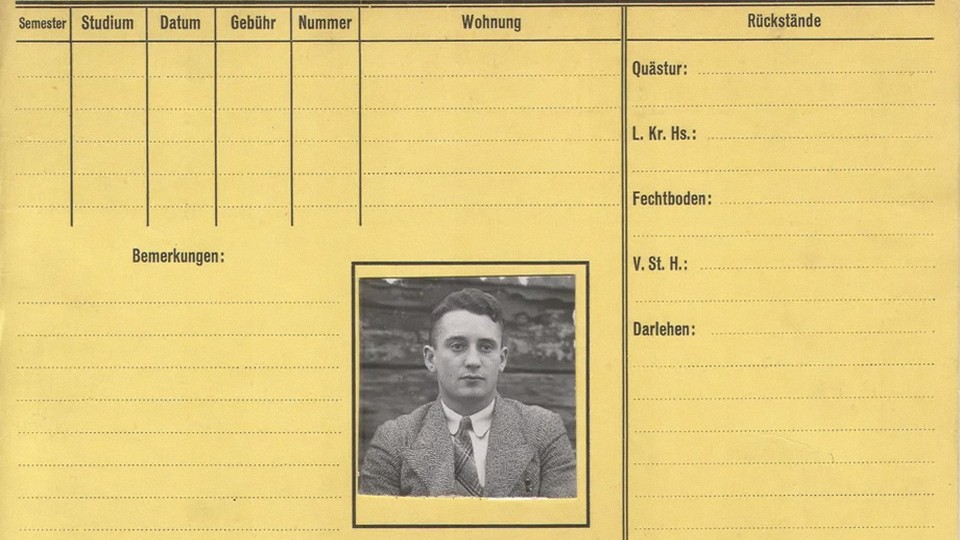

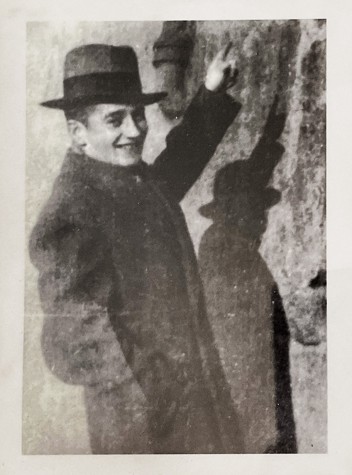

I took the two photos I had of Arthur with me. In one, Arthur was caught mid-gesture. He’s wearing a coat and a brimmed hat, and is pointing just out of frame. The other is his student ID card, and the photo is serious. The ID lists addresses for his two apartments near the Würzburg campus and the name of his father. But even the ID is tainted with catastrophe. Etched in faint pencil is a handwritten line that someone in the enrollment office must have added later. Arthur would not be returning to school. He’d died in a shooting.

The largest decentralized memorial ever created—gargantuan in scale, but miniature in its individual components—is the work of the German artist Gunter Demnig. The pieces are called Stolpersteine, or “stumbling blocks”—square brass plaques that Demnig has been setting into the pavement since 1996. He has placed close to 100,000 in more than 2,000 cities and towns across Europe. The stones are installed in front of the last known residences of victims of the Holocaust. Each is engraved with someone’s name and a line or two that describes their fate.

[Read: Escaping Nazis: The story of a girl who lived]

Demnig is 74. He books deliveries of the stones back-to-back, sometimes stopping in multiple cities in an afternoon. He has said in interviews that he was inspired to embark on the project after hearing a French rabbi quote a line from the Talmud: “True death is when someone is forgotten.”

In Gemünden am Main, I saw the stone that had been laid for Arthur’s sister. After Arthur’s funeral, she fell in love with one of Arthur’s best friends and married him. Fanny Weinberg, née Kahn, and her son, Nathan, who was about to turn 6, were both deported to Minsk and murdered. (Her husband survived.) Ryback, the author of Hitler’s First Victims, told me that he had realized that Arthur didn’t have a stone—nor did his nephew—and he recommended that, as a living relative, I ask Demnig’s office.

The town is small, with just one main street. The house that Arthur grew up in is a few doors up the road from a tourist office that advertises popular activities. A woman was sitting behind the desk there when I walked in. To one side of her was a wall covered in pamphlets. Arthur’s face was on the cover of one. The woman explained that students had researched the lives of Jewish families in Gemünden. She cried as she spread the brochure across the counter. It bears the photo from the student ID. Arthur’s face is lineless. Young.

I mentioned the Stolpersteine and wondered if she knew how to reach out to Demnig. She promised to introduce me to someone who could help. Sure enough I had an email waiting for me when I arrived back home. It was from the teacher who’d advised the students who produced the pamphlet. We went back and forth, in emails translated from English to German and back. He would handle the coordination with Demnig’s office. Would I be willing to make another trip?

In October 2021, after two pandemic-induced postponements, I returned to Gemünden to see Demnig place Stolpersteine for Arthur and Nathan. Fourteen descendants of Martha and Levi were there to meet him. To honor Arthur, Ryback came too.

Jürgen Endres—the teacher—had insisted on picking us up from the train. He stood outside the station with his students. Most had lived in the area all their lives. But two of them were newer residents. The girls had settled in Gemünden in 2015, refugees from Aleppo, Syria, who found haven in the place Opa fled.

Endres had planned an afternoon of performances and remarks for the occasion; he asked me to give a speech to close out the event. It was short, but it took me weeks to write. All that research, and I still knew most about Arthur’s final moments. I hadn’t found his diaries or letters he’d written. I knew what happened to him. I will never be able to know who he was. He is frozen at 21, on the brink of becoming.

I decided to speak about how the past can shape-shift under manipulation—how historical truths can be overwritten with a careful editor. It’s not just a matter of remembering or forgetting, but of how we tell our stories. The conclusion was the hardest to write. I didn’t know how it ended—not the speech, not the quest I’d set out on. I settled on the truth: “I am so proud to be a German Jew.”

Fewer than 400,000 Holocaust survivors are still alive. Thousands have been interviewed as part of oral-history projects, including Opa. Their photos and memories have been recorded, but I wonder whether we asked too much of the remembering. It was supposed to add up to something. “Never forget” was supposed to be our guarantee—“Never again.”

Instead, the far-right Alternative for Germany has become a potent force in German politics. One of its leaders described Berlin’s Holocaust memorial as a “monument of shame” unbecoming for a nation with so much else deserving of commemoration. In 20 states in America, Holocaust education is a required part of public-school curricula, but that hasn’t staved off a startling erosion in Holocaust awareness. About half of Millennial and Gen Z Americans can’t name a single concentration camp. More than 10 percent blame the Jews for their own extermination.

[Read: 75 years after Auschwitz, anti-Semitism is on the rise]

The Auschwitz Memorial has 1.3 million followers on Twitter. Most of its posts are short descriptions of people who were deported to the camp. But it often has to break from its usual programming, compelled to weigh in on the latest statement from a politician comparing the demonization and annihilation of persecuted people to vaccine mandates.

In 2021, the American Jewish Committee released research about the state of anti-Semitism. One in four American Jews reported experiencing an anti-Semitic incident in the previous 12 months. In New York, anti-Semitic hate crimes went up almost 50 percent from 2020 to 2021.

A slogan can’t bring about redemption. In searching for Arthur’s life amid the wreckage of his death, “Never forget” started to feel inadequate. The work of historical excavation is not just to remember what happened. It’s to sit with the gaps that no amount of research or reading can ever fill in. There are questions I will never answer about Arthur. There are millions of Arthurs.

Memorialization has its limits. I have recovered all I can about Arthur Kahn. Across the Atlantic, in Germany, a dozen students and their teacher now remember too. It mattered to me more than I’d thought it would to see Demnig wedge the stones into the ground. Arthur was there once. And so were we.

Two weeks after I returned, I woke up to an email from Jürgen Endres. It had been hard coming back to New York. I felt the same as I had when I’d visited Arthur’s grave in Nuremberg in 2019. Bewildered. I hadn’t wanted to leave him. That’s how I feel writing this now. I don’t want to be finished.

The Stolpersteine installation had made the news, and one of the stories reached the chair of the historical museum in the town of Lohr am Main, 17 minutes from Gemünden.

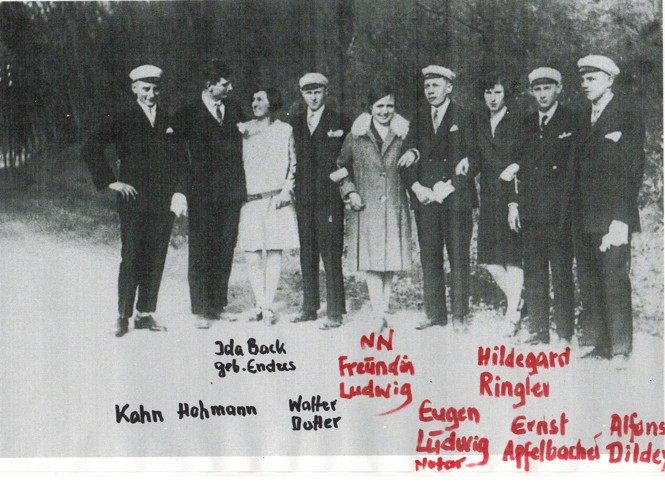

“I consider it a small sensation,” Endres wrote, “that another photo of Arthur Kahn was sent to us.”

In a note to Endres, the museum chair described how he’d found a letter about Arthur in the town’s archives, bundled with a photo. The letter was dated 1993 and had been sent to the principal of the local high school from an alumnus named Walter Dotter, a retired state insurance worker. The letter rambles, repeats itself. “I tried to keep the rather particular voice,” the person who translated it for me said, “a mix of genuine regret and an ‘official’ tone, perhaps because he is writing to the director of his old school … but perhaps also to avoid accepting guilt.”

Dotter said that he and Arthur had been not just classmates, but friends. He wrote that Arthur was the “best student of the class, popular and respected for his quiet manner.” He was appalled to learn what had happened to him.

“Arthur Kahn thus became the first victim of the Dachau murderers as a former student of the Lohr [School],” Dotter continued. “I therefore believe that I can assume this sad event is also worth a silent commemoration.”

With the note, he enclosed the photo. I hadn’t known that Arthur had studied in Lohr. Now I had the third photo of him I’d ever seen. It’s the kind of document I had been so desperate to track down. It proved what I had hoped—that there had been an Arthur before. I tried not to dwell on what happened next in the timeline.

The photo was taken at Arthur’s graduation. Dotter had written that Arthur—the class’s lone Jew—was named valedictorian. He stands on one side of the group, with a hand on his hip. There is not a Jew in the world who wouldn’t assess the lineup, consider his classmates, and hazard a guess—who went Nazi?

All of the students are dressed in their finest. Arthur is wearing a suit and a pocket square. He smiles wide, almost blinking in the sun. There he is. The man I can almost remember.