I have been a doctor for more than 20 years, 12 of which were dedicated exclusively to the practice of sleep medicine. Over the years, I have seen an enormous increase in the use of melatonin by my patients and their families. Although melatonin has helped many of my patients, there are some concerns that I have that are worth sharing.

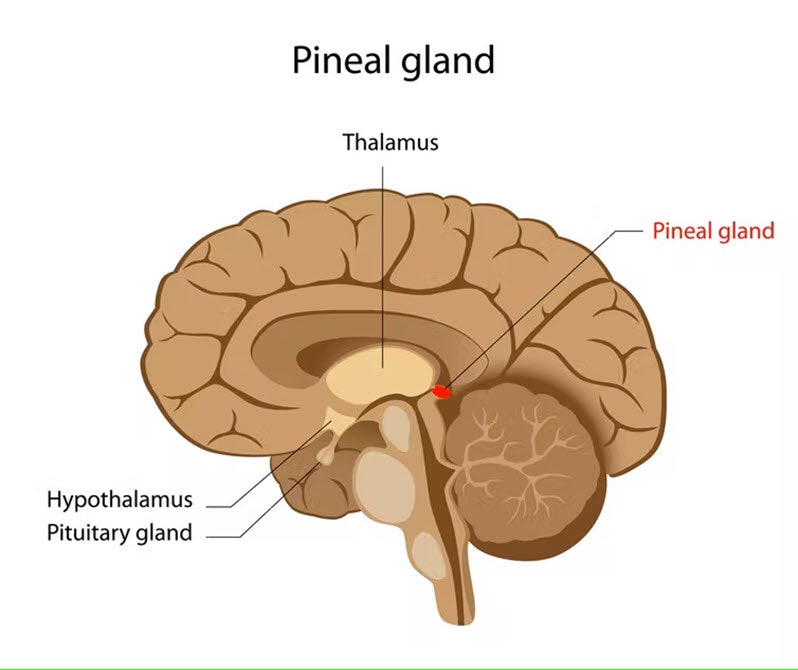

First, I am not sure most of my patients that took melatonin before my clinical evaluation knew exactly what melatonin was. Melatonin is a hormone produced by a gland in the brain called the pineal gland. The main function of melatonin is sleep regulation.

Melatonin levels increase in response to darkness, telling the brain that night has arrived and it is time to sleep. When there is a bright light, as in the morning, melatonin production shuts down and the brain knows that it is daytime.

The day-night regulation properties of melatonin and light make them the two key factors in the establishment of the internal sleep-wake clock, or what is called the “circadian cycle.”

A circadian disorder occurs when there is a mismatch between the internal clock and the socially accepted time to go to sleep or to wake up, as is seen when someone travels across time zones and has jet lag. But jet lag sometimes can occur in the absence of travel. For example, when you remain in an environment of bright lights until the late hours of the night, you fool your brain into thinking that it is still daytime. In this case, melatonin production does not occur and you don’t feel sleepy until the late hours of the night, or sometimes early hours in the morning.

I have seen many teenagers come to my clinic because they can’t sleep until 2 a.m. or 3 a.m., but they’re up watching videos on their electronic devices until late at night.

I usually recommend my patients turn the lights off at a reasonable time and expect sleepiness to start occurring within one hour. But it takes time for the natural clock to adjust to a new schedule, and often my patients prefer to use a melatonin supplement to quicken the circadian time adjustment.

With the increase in the use of electronic devices, sleep disorders have become quite common and melatonin use has increased. Because of its sleep-promoting properties, melatonin is also an incredibly attractive option for people who suffer from insomnia or sleep disruption.

Over-the-counter melatonin

In some countries, such as the U.S., melatonin can be bought without a prescription. This situation concerns me because a lack of regulation can mean an increased risk of taking a different dose or ingredients than those reported. In fact, a study of melatonin supplements found that the content of the hormone ranged from -83 percent to +478 percent of the labeled content. The researchers also found other substances that were not reported to be in the preparation, including serotonin and valerian.

In the E.U., the U.K., and Australia, melatonin is obtained only by prescription for the short-term treatment of insomnia. This approach allows for better regulation, understanding, and explanation of risks, benefits, and alternatives to the use of melatonin.

Even though melatonin is a naturally occurring hormone, it does not come without side effects, the most common being headaches and dizziness. It can also interact with other medicines, such as anticoagulants (pharmaceuticals that help prevent blood clots).

The best evidence of safety for the use of melatonin is for short-term use only (one to three months) and in low doses (0.5-1mg). The long-term effects of melatonin remain unknown.

Have I used melatonin or recommended it to my patients? Absolutely. But only when I know exactly what I am recommending it for. Insomnia can be a symptom of a sleep disorder like restless legs syndrome or obstructive sleep apnea, or it can be a symptom of another condition, such as depression, asthma, or pain.

When a sleep specialist identifies the correct diagnosis, then the treatment options can be explored. When I need to prescribe melatonin, I usually recommend starting with the lowest dose possible (0.5mg) one to two hours before their current bedtime, and I recommend that the patient turns their lights off, or dims them, before taking melatonin. I also recommend avoiding other contributors to poor sleep, such as caffeinated products after 3 p.m., heavy exercise in the evening, or the use of electronic devices before bedtime.

This article was originally published on The Conversation by Lourdes M. DelRosso at the University of Portsmouth. Read the original article here.