The snow is gone, the sea ice has melted, and mosquitoes are voyaging north of the Arctic Circle in greater numbers. In the normally snow-bound landscape, white Arctic hares now hop among green bushes.

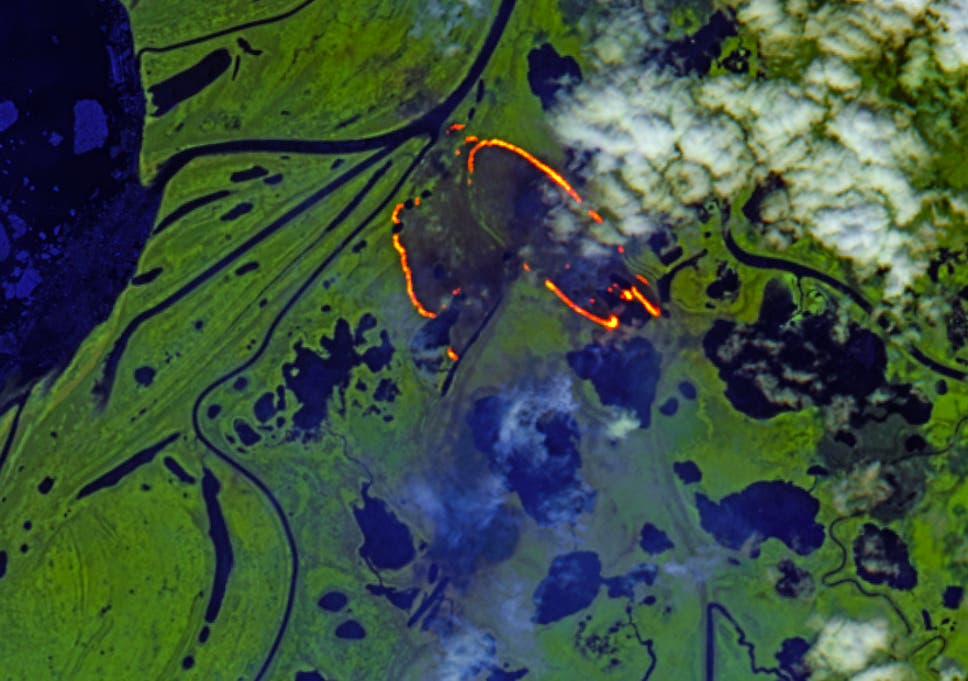

Amid the warmth, the record wildfires that tore across the tundra last summer are returning: the European Union’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service is now watching these fires via satellite.

The service said parts of the Arctic were more than 10 degrees warmer than usual during May.

It is thought many of the fires erupting are “zombie fires”, so-called because despite the cold, wet winter, they have nonetheless continued to smoulder, often in peatlands, and then reignite when warmer drier weather arrives.

This can then lead to large new fires, which threaten the existence of the peatlands — a major carbon sink.

Peatlands in the northern hemisphere store more carbon than all the world’s rainforests combined. If they were to burn, the massive amounts of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere would immediately render all efforts to control emissions futile.

Thomas Smith, assistant professor in environmental geography at LSE told The Independent: “The fires spotted in the Siberian Arctic Circle might be zombie fires. They are occurring in places that burnt last summer.

“Some of them overlap with last year’s burn scars, and some of them are burning on areas with carbon-rich peat soils, [which provides] good fuel for an overwintering fire.

“However, this region is also known for having lots of human ignitions for various traditional agricultural practices, so it’s very difficult to confirm overwintering fires just from looking at the satellite images. With wildfires, a good rule of thumb is that they are most likely to have had a human ignition.”

Although fires are recognised as playing an essential role in the Arctic, there are concerns the increasing number and size of the fires could bring major changes to the environment with global implications.

Dr Smith said: “Fires are quite normal in Arctic ecosystems. They often play an important role in tree reproduction and regeneration. The carbon emitted from wildfires is re-sequestered when the vegetation grows back. However, an increasing frequency and severity of fires might lead to permanent changes in these ecosystems where we could see the replacement of forests with shrubs or grasses.

“This has important implications for carbon emissions, because the carbon lost in the fires may not be re-sequestered in the near future. Further, if the fires have ignited peat soils, the carbon lost from these fires has taken thousands of years to accumulate, something that cannot be reversed within timescales of concern for climate change.”

While satellite monitoring of the region has improved in recent decades, scientists say the evidence, from areas including Alaska and Siberia indicate the phenomenon is becoming more common.

Dr Smith said: “It’s not surprising … increasing fire activity coupled with permafrost melting associated with global warming can only increase the likelihood of deep seated fires as more fuel — soil and vegetation — is made available to burn.”

Writing at the end of May, Copernicus senior scientist Mark Parrington explained why the service monitors the fires.

“We incorporate satellite observations of active fires into our Global Fire Assimilation System to monitor them and estimate the associated emission of pollutants so that we can then predict the transport of the resulting smoke in the atmosphere,” he said.

“Such forecasts are used in air quality apps to help people limit their exposure to pollution, as well as by policymakers and local authorities to manage the impact of fires.”

As well as the highly visible fires, the rapidly warming Arctic ecosystem is alarming those who remember significantly different seasonal variations.

“This spring the nature at the Taymyr Peninsula broke all climate records and really surprised old-timers,” geographer Vasily Sarana, a researcher at the scientific team of the Putoransky Nature Reserve in northern Russia, told the Siberian Times.

He added: “Snow at the spurs of the Putorana mountains melted long ago, unusually for this time of year. There is not a snowflake left in the tundra, so white hares are hopping about the bushes looking clearly bewildered. They were obviously not ready for such an early spring — just like the rest of our nature.”

Meanwhile, orca whales have been seen hunting seals in bays normally bound by ice.

This lack of snow and ice over land and sea helps form part of a vicious feedback cycle where the uncovered earth and oceans absorb more heat than when they’re under their highly-reflective winter cloak.

This exacerbates warming, which can have unexpected consequences: One reason the number of fires in Arctic environments may be increasing is that the warming climate is leading to more frequent lightning strikes. This provides the ignition which is then fuelled by the warmer, drier material on the ground.