Frangipani plants and coconut trees front the three-story villa on Sentosa Island where Myanmar tycoon Tay Za stays when he’s in Singapore. It’s one of two houses his family owns in a development overlooking the South China Sea known as a playground for the wealthy. A short drive away is the Marina Bay Sands casino, where he would often show up carrying a duffel bag stuffed with cash. On a sunny day in June, a yellow Ferrari F8 Spider and a Mercedes were parked outside one of the villas.

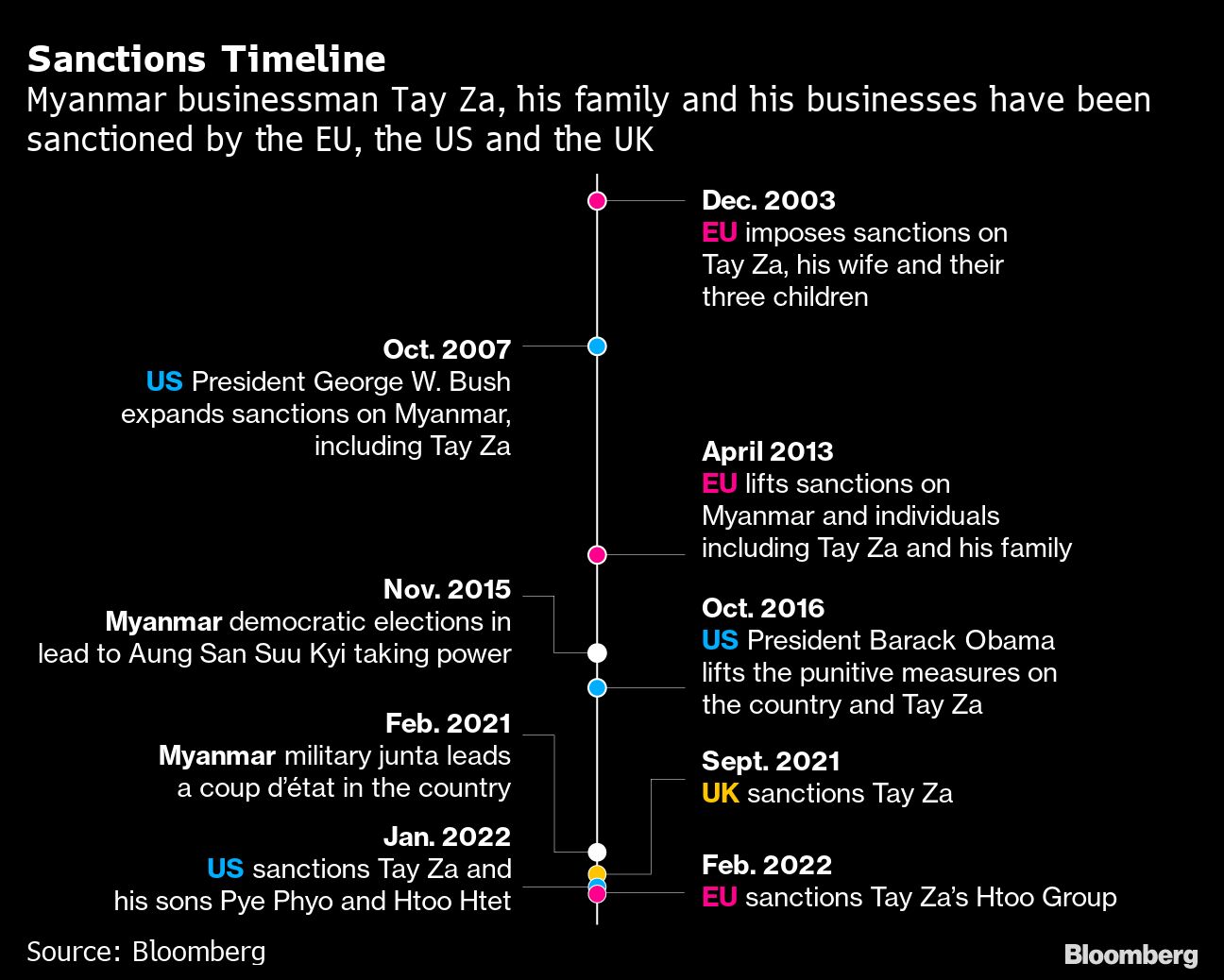

Singapore has long been a haven for sanctioned Myanmar businessmen, including Tay Za, who has been accused by the US and others of supplying arms and equipment to the military. He has maintained the right to live and work in Singapore despite sanctions first imposed by the US in 2007 and has incorporated about 10 companies there with operations in palm oil, teak and aviation. The US sanctions against him and other supporters of the regime were lifted in 2016 after democratic elections in Myanmar, then reinstated earlier this year following a February 2021 coup that forcibly removed Aung San Suu Kyi from leadership.

Most Asian countries, including Singapore, don’t support the sanctions. Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has said they would only hurt the people of Myanmar and have pushed that country closer to China. When asked about Tay Za and Singapore’s policy on Myanmar, a spokesperson for the Foreign Ministry pointed to previous statements by Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan, who called the situation there “a tragedy.” The minister has said Myanmar needs to resolve its conflicts internally and that people shouldn’t overstate his country’s influence.

That stance is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain as the US ramps up pressure on the junta and global financial regulators weigh blacklisting the country. There are signs Singapore is moving away from its policy of not interfering in the affairs of neighboring countries. It has criticized the military regime, asked banks to heighten their scrutiny of financial flows to Myanmar and stopped authorizing the transfer of any items that may be used to inflict violence against unarmed civilians. But sanctioned arms dealers including Tay Za, who has denied the allegations, continue to operate other businesses openly in the city-state.

“Singapore was at first very reluctant to impose sanctions on the military government, fearful of the impact that it would have on the financial sector,” said Zachary Abuza, a professor at the National War College in Washington who specializes in Southeast Asian politics. “It has started to crack down on some military-linked corporations that are operating in the city-state, but there remain a large number conducting business in Singapore, which provides a financial lifeline for the military as well as a conduit of weapons, munitions and spare parts.”

Leaked 2007 US State Department cables called Tay Za Myanmar’s “ number one crony businessman,” citing his connections with Russian aircraft manufacturers. One of the cables, written by a US embassy official in Yangon and published by WikiLeaks, described how he leveraged his relationship with a Russian ambassador to become the sales representative for companies that supplied Myanmar with arms, ammunition, MI-17 helicopters and MiG-29s.

The UK sanctioned Tay Za in September 2021, saying he “is associated with the military through his extensive links with the former and current junta regimes.” The US Treasury added him to its sanctions list in January, saying he had provided weapons and equipment to the armed forces and traveled to Russia in May 2021 with the head of Myanmar’s air force at the time. The US also sanctioned Tay Za’s sons, Pye Phyo and Htoo Htet, who were deemed “instrumental” to his dealings with the junta, as well as his company, Htoo Group.

Russia was second only to China in selling arms to Myanmar over the 10 years ending in 2021, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, or Sipri, which tracks international arms sales. The group said 30 combat-capable aircraft were delivered in the second half of that period, including 20 from Russia and 10 from China. While most countries build up stockpiles for defense, Myanmar’s military, known as the Tatmadaw, has employed them for campaigns against its own citizens and the Rohingya minority, Sipri said.

Siemon Wezeman, a senior researcher at Sipri’s arms-transfer program, said the use of middlemen like Tay Za is common in countries such as Myanmar. “They have the knowledge, the contacts and help oil the wheel,” he said. “It’s not that they are doing anything illegal, but they can help facilitate financing and transportation of arms.”

As recently as 2018, when sanctions against Tay Za weren’t in effect, representatives of his Yangon Aircraft Engineering Co. met with Myanmar Air Force delegates to discuss the conversion of ATR 72 aircraft for cargo and troop transport at an approximate cost of $550,000 each, according to leaked minutes of the meeting published by Justice for Myanmar, a group that investigates and campaigns against entities supporting the junta. Another leaked document from November 2017 cited Tay Za’s Myanmar Avia Export Co. as the partner of JSC Russian Helicopters.

A 2019 United Nations Human Rights Council report called Tay Za’s Htoo Group, one of “the largest crony companies” in Myanmar. It was among donors to the Tatmadaw in September 2017, the report said, after the armed forces began what it called “clearance operations” against the Muslim Rohingya population in western Rakhine state that resulted in several thousand deaths and the displacement of an estimated 870,000 people.

Major General Zaw Min Tun, lead spokesman for Myanmar’s ruling State Administration Council, declined to answer questions about Tay Za, arms sales or sanctions against the country. “We can’t answer these,” the council’s information office wrote in an email.

‘1,000% Never’

Tay Za denies he’s an arms merchant. In a 90-minute interview from Putao, a picturesque town in the Himalaya foothills where he owns a resort, the 58-year-old businessman said he has provided only transportation equipment, not weapons, to Myanmar’s military. He said he has suffered financial setbacks as a result of the sanctions, including having to close his airline because he couldn’t obtain insurance, and is now semi-retired because of health issues.

“I don’t trade arms,” he said, his round face becoming animated on a computer screen. “1,000% never.”

His two sons joined the call. Heir apparent Pye Phyo, 35, dialed in from Yangon in Myanmar, and Htoo Htet, 29, who runs the family bank, was at the W Hotel on Sentosa. Both went to an international school in Singapore, speak excellent English, and chipped in with occasional translations for their father.

“The media has caricatured my relationship with the armed forces,” Tay Za said, explaining that he had a good rapport with the military until 2011, though his “proximity to the government at the time was exaggerated.” He insisted he didn’t go to Moscow last year because of pandemic travel restrictions, disputing US Treasury allegations and a May 2021 report in the Irrawaddy, a publication run by Myanmar journalists in exile.

The publication, citing unnamed sources, said he flew in a private jet from Singapore to Naypyidaw, the capital of Myanmar, for meetings with senior junta officials before attending a military exhibition in Moscow with Myanmar’s then air force chief. “Those allegations were entirely false,” Tay Za said.

A copy of Tay Za’s Myanmar passport seen by Bloomberg News bears no stamps for travel since its issuance in April 2020. But holders of a Singapore employment pass like Tay Za can have their passports scanned electronically rather than stamped, according to the website of Singapore’s Immigration & Checkpoints Authority, which processes arrivals and departures. An ICA spokesperson said the agency couldn’t comment about individuals and declined to say whether Tay Za left Singapore in May 2021.

Other records provided by a representative for Tay Za, which the person said showed his comings and goings from the gated residence on Sentosa, show that he left the house at 1 a.m. on May 17, 2021, and returned at 4 p.m. on May 21 – enough time to attend the military exhibition from May 20-22, but not enough to quarantine for 21 days in a designated facility, as he would have been required to do under the city-state’s pandemic rules in effect at the time.

Aung Zaw, editor-in-chief of the Irrawaddy, said he stood by his publication’s story. The US Treasury declined to comment.

Tay Za said he would meet in Singapore to answer further questions, then withdrew the offer. A representative for his company said in an email that the 2018 plane-conversion project was “civilian in nature” and did not proceed. He also denied that Myanmar Avia Export was a partner of any international firm.

While the latest sanctions haven’t forced the junta to change its policies, they have taken a toll on Tay Za. The UK has banned him from traveling to its territories. A joint venture with Singapore-based Banyan Tree Group for management of 17 hotels in Myanmar has stalled as a result of what a Banyan Tree spokesman describes as “the present situation.” And earlier this year, the Marina Bay Sands, owned by US-based Las Vegas Sands Corp., told him he’s no longer welcome to gamble there. (That ban may be a boon for Tay Za, who had lost about $70 million at baccarat tables there, according to a person with knowledge of the matter. ) The casino company declined to comment.

Still, he is free to come and go as he pleases. “Singapore remains a central business and financial hub in the region, with corporate services of the highest standard,” Tay Za’s representative said. He “enjoys the Singaporean lifestyle, food, and environment, and over time has built strong relationships with friends in Singapore.” The representative declined to comment about Tay Za’s wealth or gambling habits.

Family Connections

Tay Za’s family connections helped pave his way in both the military and business worlds. His father, Myint Swe, took the top job at the Tatmadaw Military Research Unit, an equivalent to the US Central Intelligence Agency, after completing a training course at Fort Benning in Georgia, according to a book published by the family after his 2008 death. Myint Swe’s friendship with Ne Win, the army general who seized power in a 1962 coup, helped his youngest son win the armed forces’ trust.

Tay Za married Thida Zaw in the early 1980s after dropping out of a military school. Her family owned Htoo Group, which at the time operated a rice-milling business. Tay Za expanded it into teak trading, aviation, construction, hospitality and banking while making friends with top officials, including Than Shwe, head of state for two decades until 2011.

According to one leaked US cable, Tay Za hired the ruling junta’s children, giving them senior roles in his businesses despite their lack of experience. In return, the document said, he was granted lucrative concessions, including one of the few licenses to import cement when the country was building its new capital Naypyidaw. When Tay Za won an exclusive liquor import permit, he gave the 20-year-old son of a former air force chief $200,000 to operate retail outlets, the cable noted.

Two years after President Bill Clinton first blacklisted Myanmar in 1997, Tay Za incorporated his first two companies in Singapore, Pavo International Pte and Pavo Trading Pte. Company filings say they were for “wholesale of logs, sawn timber, plywood and related products.” In 2004, a year after President George W. Bush imposed an import ban on products from Myanmar, Tay Za registered Air Bagan Holdings Pte. Another Singapore-based entity, Terrestrial Pte, started in 2007, the year Bush expanded the punitive measures.

Oasis of Calm

Like many wealthy people, Tay Za was drawn to Singapore because it offers stability and anonymity. The city-state is an oasis of calm compared with its Asian neighbors. Since its separation from Malaysia in 1965, it has been governed by one party, co-founded by Lee Kuan Yew, who developed the country into a global financial and commercial hub.

As the world’s third-largest offshore financial center after Switzerland and Hong Kong, Singapore attracts funds from all over. Firms there held $3.5 trillion worth of assets in 2020, about three-quarters of them from overseas, according to a central bank survey. Banks and wealth managers cannot disclose clients’ personal information except to regulators or under court order.

Business incorporation is a big industry in Singapore, and more than 560,000 firms were registered there as of July. Serena Lee Chooi Li is among the beneficiaries. The Malaysian lawyer is or has been the corporate secretary of more than 200 companies, according to her 147-page profile at Singapore’s corporate registry. Among the active ones are Tay Za’s Pavo Trading, where Lee has been secretary since 1999. She also serves or has served about a dozen other entities linked to Tay Za and his family, most of them registered at the same business address on the 6th floor of the Bharat Building, where Lee’s firm is located. Lee declined to comment.

Pavo Trading has been listed by the US as part of Tay Za’s financial network as far back as 2008. Today, the company remains “live” and solvent on Singapore’s corporate registry, which shows the most recent annual general meeting was held June 30, 2021. Tay Za is listed as managing director, director and majority shareholder. Thida Zaw, from whom he is separated, is the other shareholder. The company is named after El Pavo, one of his favorite cigar brands.

While only two of the 10 Singapore-based firms listed under his name are active, the real picture may be more complicated. A dozen other companies were held by his employees or family members as of this year. His sister, Thida Swe, owns Frontier Gold (Singapore), which was active until May. His younger son, Htet Htoo, is a shareholder and director of three Singapore companies. Teo Ah Peng, an employee, is or has been a director of six active companies, some of which have the same address at the Bharat Building.

Tay Za’s Sentosa villa was bought with a mortgage from the Singapore unit of Malayan Banking Bhd., Malaysia’s largest bank, according to records at the local land authority. Although the amount of the mortgage isn’t disclosed, a villa of similar size can fetch as much as S$15 million ($10.7 million) in today’s market, according to property firm ERA Singapore. A house held under his sister’s name, facing one of the island’s golf courses, has a mortgage with United Overseas Bank Ltd., Singapore’s third-largest bank. That house was purchased in 2012 for S$15.3 million, public records show. A spokesperson for Maybank said it couldn’t comment about individual customers but that it follows all applicable laws and regulations. UOB didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Singapore is the largest foreign investor in Myanmar with a total of $25 billion flowing into the poorer country since 1989. Keppel Corp., which counts state-investment firm Temasek Holdings Ltd. as its biggest shareholder, has investments in Myanmar, as does sovereign wealth fund GIC Ltd.

The money has continued to flow since the 2021 coup, despite the sanctions and the deaths of more than 2,000 civilians, according to an estimate by the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, a human rights group based in Thailand. Myanmar government records show that $297 million of investments came in from Singapore in the six months ending in March.

US Pressure

The 10 members of Asean, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, have generally avoided criticizing and interfering in each other’s affairs. But that has been changing since the coup. Asean has taken the position that Myanmar’s leaders have failed to observe an April 2021 agreement to end violence in the country, and it excluded them from a summit in Brunei last October. Earlier this year, Singapore’s foreign ministry called for the release of all political detainees in Myanmar, including Aung San Suu Kyi. At an Asean meeting at the White House in May, an empty chair was put out at a lunch to represent the overthrown civilian government.

Singapore usually complies only with sanctions imposed by the United Nations, rather than unilateral measures, and the UN hasn’t taken such action against Myanmar. But Singapore hit Russia with targeted financial sanctions in March after the invasion of Ukraine, even though the UN didn’t act.

The US has been pressuring its Asian ally to get tougher on Myanmar, and there are signs that Singapore is responding. Last October, State Department Counselor Derek Chollet visited the Monetary Authority of Singapore, the country’s central bank, and said the city-state has “significant financial leverage” over Myanmar. His statement came after the central bank said in February 2021 that it didn’t find “significant funds” from Myanmar companies and individuals at banks in Singapore.

That position hasn’t changed, according to a spokesperson for the central bank, who acknowledged that financial institutions in Singapore have been placed on “heightened alert in relation to risks emanating from the situation in Myanmar.” In September, Singapore said in a statement at a United Nations Human Rights Council session that it expects banks “to remain vigilant to any transactions that could pose risks, including dealings with companies and individuals subject to financial sanctions by foreign jurisdictions.”

The Financial Action Task Force, a Paris-based global watchdog, placed Myanmar under increased monitoring in February 2020 for failure to strengthen its anti-money-laundering controls and will consider blacklisting the country at a meeting starting Oct. 18.

DBS Group Holdings Ltd., based in Singapore and Southeast Asia’s largest lender, has closed accounts of some Myanmar nationals residing in Singapore, including several who have raised funds to fight the junta, people familiar with the matter said. In a letter sent to some account holders in June, DBS said it had observed “unusual activities” involving the accounts and would be closing them in 30 days. Some of these individuals later were able to open new accounts at other Singapore-based banks, according to the people familiar.

A spokesperson for DBS said the bank doesn’t comment about individual clients and doesn’t impose any political views on its customers. Unusual activity, the spokesperson said, “can be linked to criminal activity, contravenes our policies, or otherwise represents an unusual or suspicious increase in size and volume of transactions.”

Singapore’s stricter stance has also affected companies that haven’t been sanctioned and have no obvious connections to the junta. “We are seeing that banks these days are increasingly strict when it comes to new account openings by Myanmar individuals or entities,” said Chester Toh, a partner at Rajah & Tann, one of Singapore’s largest law firms, who helped set up the firm’s practice in Myanmar. “Banks which used to be quite happy to do business with Myanmar businesses are getting cold feet, and it has been difficult for Myanmar businesses looking to restructure or pivot away from Myanmar.”

Meanwhile, Myanmar’s central bank, facing deteriorating economic conditions, plunging local currency and a shortage of dollars, has imposed restrictions, including a requirement that firms earning in foreign currencies convert their revenue into Myanmar kyat within one working day at a fixed rate much lower than the black market price. In July, the regulator asked debtors to halt repayments of foreign loans to defend the nation’s dwindling foreign-exchange reserves.

There is no reliable estimate of how much Myanmar money is parked in Singapore, but several individuals sanctioned by the US have long-term employment passes in the city-state and businesses there, according to corporate registry filings.

Naing Htut Aung, accused by the US in March of procuring arms from Chinese companies while having ties to the junta leadership, owns at least two companies registered in Singapore. His address is a 44th-floor apartment at the Orchard Residences, atop a mall on the country’s most famous shopping street. The unit is owned by his wife, Wai Wai Yin, who is not sanctioned and has been a director of his Singapore-based companies, government filings show. He didn’t respond to emails seeking comment.

Aung Hlaing Oo, described by the US Treasury as a central figure in planning a weapons-manufacturing plant in Myanmar, owns M C M Pacific Pte, a steel-trading company registered in Singapore since 2006. United Overseas Bank has been the firm’s banker, according to a 2017 filing. Neither Aung Hlaing Oo nor his company responded to requests for comment.

Tun Hlaing, director of the Myanmar Directorate for Defense Industries, has been linked to several Singapore companies. His daughter Thet Hnin married Tay Za’s son Pye Phyo in 2020. The wedding was held in a resort town near Mandalay, and the groom arrived in a red Ferrari F8 Spider. Tay Za, wearing a black blazer and matching beret, can be seen in a lavishly produced video posted on YouTube crying during the ceremony before playing on a drum set at the dinner reception held in a glass conservatory lit by hundreds of bulbs.

Thet Hnin Hlaing is involved in her father’s business and was a director of two of his Singapore companies, registry filings show. Her father is also a shareholder in a Singapore restaurant business, Vino Vovo Pte, which reported revenue of S$2.93 million in the fiscal year ended November 2019. Tun Hlaing didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“Singapore remains the business hub for military-linked companies,” said Yadanar Maung, a spokesperson for Justice for Myanmar. The organization said it welcomes more vigilance by Singapore banks and the stock exchange regulator, which suspended trading in Emerging Towns & Cities Singapore Ltd. after the group published information about that company’s links to the junta. “But more needs to be done,” she said, “including targeted sanctions against military businesses, and an arms embargo that will stop Singapore-registered companies procuring weapons and dual-use goods for the Myanmar military.”

Shrinking Empire

Tay Za’s Htoo Group has shrunk to about 15,000 employees, according to Pye Phyo, down from the 60,000 reported by the Financial Times in 2011. Corresponding banking relationships for his Asia Green Development Bank Ltd. have been terminated, said his son Htoo Htet, who declined to identify those former counterparties. Gone too is the credit-card business, as Visa Inc. and Mastercard Inc., both US firms, can no longer do business with the bank.

Tay Za can’t start a process for removal from the sanctions list because of “the current security situation as well as financial constraints,” the company representative said. In an earlier attempt in 2014 to lift sanctions, Tay Za engaged the law firm founded by John Ashcroft, a former US attorney general under George W. Bush. The firm would have been paid between $500,000 and $1 million, depending on how quickly it got results, according to a copy of a previously unreported contract seen by Bloomberg News.

Tay Za’s former wife was removed from the US list in 2015 on grounds of their separation. President Barack Obama lifted sanctions against Myanmar and Tay Za the following year. The representative for his company declined to disclose what if any fees were paid to Ashcroft’s firm. Neither Ashcroft not his firm responded to requests for comment.

The removal of sanctions led to a flood of foreign investment. That year, Myanmar’s economy was among the fastest growing in the world at 10.5%. But conflicts erupted with ethnic groups seeking independence, and in 2017 the armed forces responded to an attack by a militant Rohingya group that resulted in what the UN called “ethnic cleansing.”

The sanctions imposed after the 2021 coup have pushed the junta closer to Russia and China. New arms dealers have emerged, including Kyaw Min Oo, 40, who used to work for Tay Za, according to a person with direct knowledge of the matter. Now managing director of Yangon-based Sky Aviator Co., he registered at least five companies in Singapore from 2015 through 2017 but stepped down from all of them in April, after Justice for Myanmar published an August 2019 letter he wrote to the Myanmar air force saying Sky Aviator is the “exclusive local representation” of Russian Helicopters. In June, the UK added Sky Aviator to its sanctions list. Sky Aviator and Russian Helicopters didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Chollet, the US State Department official, says Singapore has been a good partner in helping isolate Myanmar’s military regime. But Hunter Marston, an adjunct research fellow at La Trobe University in Melbourne who has followed developments in Southeast Asia since 2007, takes a dimmer view.

“Sanctions have never worked in Myanmar, or arguably anywhere else,” Marston said. “They have almost always hurt the people of Myanmar, while the generals have found ways to park the money overseas and distribute the spoils of wealth to their own loyalists within the country. The regime will not cave due to sanctions.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.