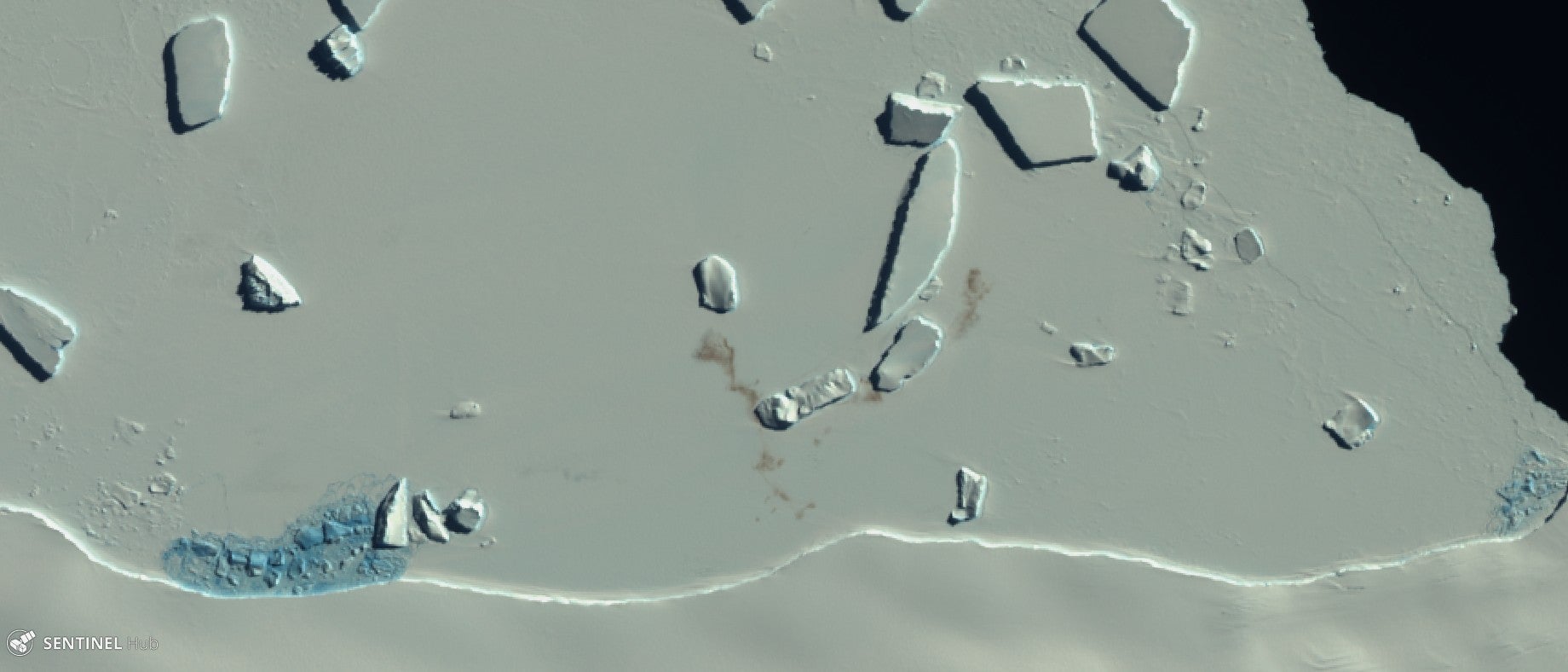

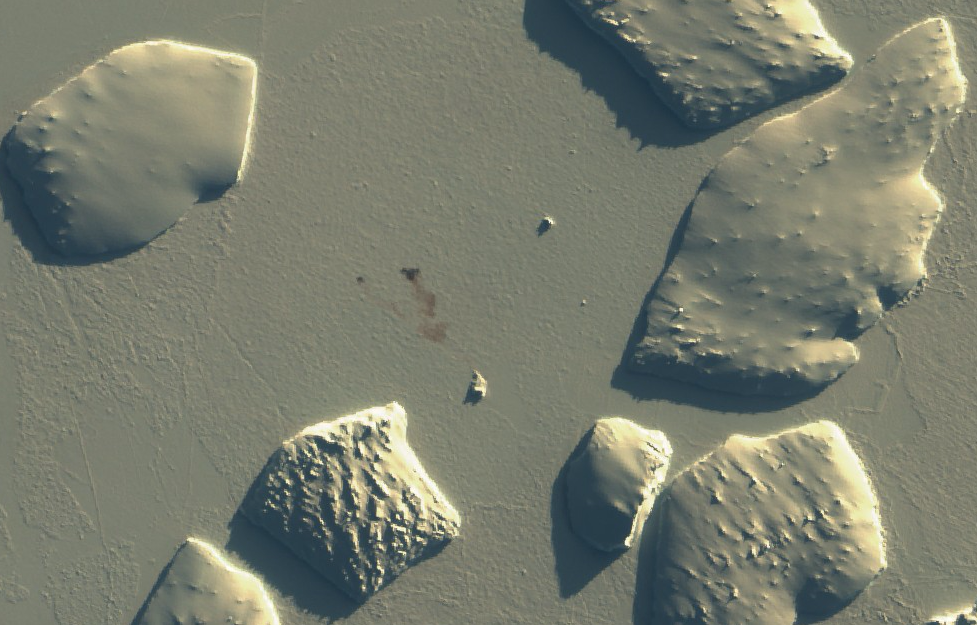

Satellite mapping technology has located 11 previously unknown emperor penguin colonies in Antarctica based on mapping the brown-red guano stains the birds leave on the ice.

The new colonies represent a 20 per cent rise in the number of known emperor penguin colonies in Antarctica, and provide a new and important benchmark for scientists studying the impacts of the climate crisis on the world’s most southerly continent.

Of the 11 new colonies, three had previously been identified, but had not been confirmed. There are now known to be 61 emperor penguin colonies scattered around the continent.

“This is an exciting discovery,” said Dr Peter Fretwell, a geographer at the British Antarctic Survey who led the satellite mapping study.

“The new satellite images of Antarctica’s coastline have enabled us to find these new colonies. And whilst this is good news, the colonies are small and so only take the overall population count up by 5-10 per cent to just over half a million penguins or around 265,500 – 278,500 breeding pairs”.

Emperor penguins need sea ice to breed and are located in areas that are very difficult to reach and study because they are remote and often inaccessible with temperatures as low as −50C (−58F).

For the last 10 years, British Antarctic Survey scientists have been looking for new colonies by searching for their guano stains on the ice.

Emperor penguins are known to be vulnerable to loss of sea ice, their favoured breeding habitat.

With current projections of climate change, this habitat is likely to decline. Most of the newly found colonies are situated at the margins of the emperors’ breeding range. Therefore, these locations are likely to be lost as the climate warms.

Dr Phil Trathan, head of conservation biology at the British Antarctic Survey, has been studying penguins for the last three decades. He said: “Whilst it’s good news that we’ve found these new colonies, the breeding sites are all in locations where recent model projections suggest emperors will decline. Birds in these sites are therefore probably the ‘canaries in the coalmine’ – we need to watch these sites carefully as climate change will affect this region.”

The study found a number of colonies located far offshore on areas of sea ice which had formed around icebergs that had grounded in shallow water.

These colonies, up to 180 km (110 miles) offshore, are a surprising new finding in the behaviour of this increasingly well-known species.

The research is published in the journal Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation.