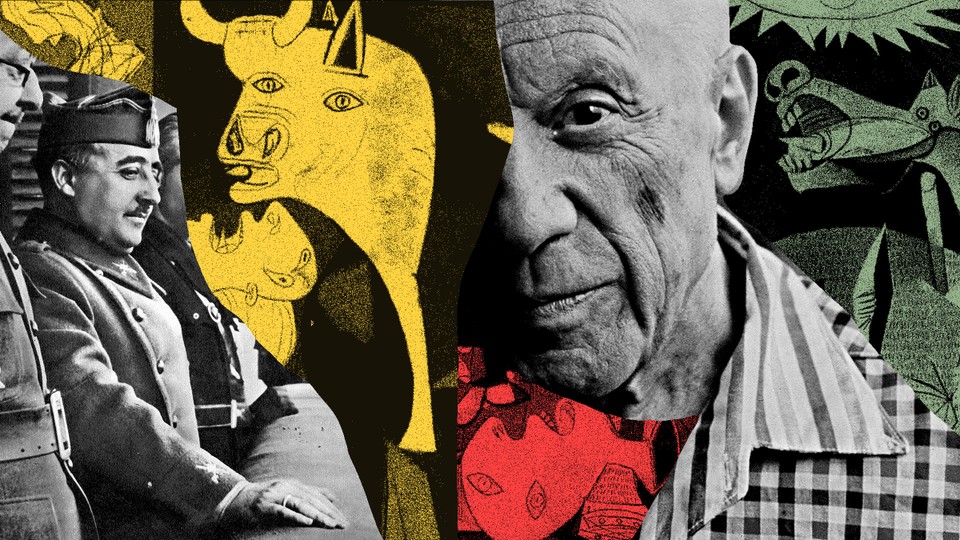

When it comes to art against tyranny, no work is more seared into our consciousness than Guernica, Pablo Picasso’s dark, howling mural against fascist terror. Created in 1937 at the height of the Spanish Civil War, it has in the 85 years since become a universal statement about human suffering in the face of political violence. Throughout World War II, it stood for resistance to Nazi aggression; during Vietnam controversies such as the My Lai massacre, protesters invoked it against the U.S. military. Today, its shrieking women and lifeless bodies conjure the corpse-strewn streets of the Kyiv suburb of Bucha after Vladimir Putin’s brutal assault.

But Guernica’s enduring status was hardly foreordained. Picasso was deeply apolitical and had shown little interest in the Spanish Civil War before he created it. Nor had he ever done a public mural, let alone one about a bombed city. And the work was so disdained when it was first shown that it very nearly didn’t make it past its debut.

The story begins in the fall and winter of 1936–37, amid Europe’s first great military confrontation with fascism. From the outset of the war that summer, there was blood in the streets of Barcelona, where Picasso’s mother and sister lived. In September, in an attempt to draw international attention to its plight—and without, it seems, consulting him—the Spanish Republican government named Picasso director in absentia of the Prado, the country’s revered national museum. Nevertheless, two months later, Franco’s forces, aided by Hitler’s planes, were besieging Madrid, forcing a frantic evacuation of the Prado, which suffered a direct hit on November 16. Then, in February, Franco captured Málaga, Picasso’s hometown.

Yet through all of this, Picasso was back in Paris, mired in personal turmoil and emotionally detached from the war. He was still in the grips of a bitter and drawn-out legal battle with his estranged wife, Olga Khokhlova—having just ceded to her his beloved country house, Boisgeloup—while managing his two rival mistresses, Marie-Thérèse Walter and Dora Maar. Fearful that his art would be claimed by Olga’s lawyers, he had spent much of the previous year not painting at all. And while his friends were consumed by the vicious fighting, he was seeking escape in carnal pleasures. “In Spain they’re killing each other & he wallows in brothels,” the Irish Italian art scholar Margaret Scolari Barr observed after meeting Picasso in Paris.

Instead of painting, he spent long hours at the Café de Flore. And when he did make art—apart from the satirical comic strips he had started but not yet finished, called The Dream and Lie of Franco—there was hardly a trace of the war in his work. Four days after the fall of Málaga, he painted an absurdist scene of two robotlike nudes playing with a toy boat on the beach. “Picasso was joking, trying to shock, playing at contradictions,” the critic John Berger wrote. “Because he didn’t know what else to do.”

Then, one afternoon in late April, Picasso was sitting at his usual table at the Flore when the Spanish poet Juan Larrea jumped out of a taxi and accosted him. That winter, Larrea had helped persuade Picasso to create a large mural for the Spanish Pavilion of the 1937 Paris World’s Fair that summer. But months had gone by, and Picasso had done no more than a few sketches. Now—according to Larrea’s friend, the Basque painter José Maria Ucelay, who later described the encounter—Larrea had an idea: A historic Basque town had just been completely destroyed by Hitler’s planes. What if he made the mural about that?

In Ucelay’s account of the meeting, Picasso demurred. It was not his kind of theme; he wasn’t even sure what a bombed city looked like. But then he read about the atrocity in the French papers and saw the pictures. He couldn’t get them out of his head. That weekend, he stayed in his studio and furiously began to sketch: a woman holding a lantern; a majestic, terrified, writhing horse; a woman, upturned in agony, grasping the limp body of a young child; a fallen warrior; an appalling pile of twisted limbs; a menacing bull; a petrified bird.

Suddenly, something had snapped inside this jaded, middle-aged man who’d spent more than nine months sipping coffee as the world collapsed. Maar was stunned by what she called his “indignation”; José Bergamín, the Malagueño poet and ardent anti-fascist who had become a close friend, could only describe it as “Spanish fury.” Man Ray, the photographer and surrealist who had been part of Picasso’s circle since the early 1920s, had never seen him react this way to world events. Having shut out the war in Spain for so long, another friend, the publisher Christian Zervos, noted, Picasso now let his paintbrush explode with “distress, anguish, terror, insurmountable pain, massacres, and finally peace found in death.”

First in an intensive series of sketches and studies, and then on the giant canvas itself, Picasso’s tableau of horror, with its contorted faces and agonized animals, rapidly took shape; in just 35 days, the thing was done. For any painter, it was an improbable feat. For an artist in his mid-50s whose life was in disarray and who had, just two years earlier, almost stopped painting altogether, it was an astonishing, athletic act of self-reinvention.

Eleven and a half feet high and more than 25 feet across, Guernica should have been a sensation when it was unveiled at the Paris World’s Fair. Occupying the entire back wall of the entrance hall of the Spanish Pavilion—a simple steel-framed glass box, designed by the artists Josep Lluís Sert and Luis Lacasa—it confronted viewers with unremitting blacks and grays and whites; like the burnt Basque city, there was not a flicker of color in the ashes of human life that Picasso had depicted. Along with Guernica, the pavilion featured another mural, by Joan Miró, and a fountain by Alexander Calder, as well as war photographs and a film program organized by the director Luis Buñuel. Here was Republican Spain, even as it fought for its life, making a case that art could be both aesthetically avant-garde and politically urgent.

But it was a case that almost no one wanted to hear. By nearly every measure, Picasso’s huge, dark painting stalled at the starting gate. Le Corbusier, the architect who reviewed all the murals at the World’s Fair, wrote that Guernica alone “saw only the backs of visitors, for they were repelled by it.” Sert, who was by his own account at the pavilion constantly during its four-month run, was struck by the almost-universal disdain. “The people came there, they looked at this thing and they didn’t understand it,” he said.

The Spanish and Basque governments hated the mural. President José Antonio Aguirre snubbed Picasso’s offer to give the work to the Basque people; Ucelay, the Basque painter, called it “one of the poorest things ever produced in the world,” adding that Picasso was just “shitting on Gernika.” Several Spanish officials suggested taking it down and replacing it with a different work altogether. Buñuel, a notorious radical in his own right, found it so unpleasant that he said he “would be delighted to blow up the painting.”

So little sympathy did Guernica generate that the French papers greeted it with almost complete silence. Despite nonstop daily coverage of the Expo, Excelsior, L’Intransigeant, Le Temps, Le Figaro, and Le Matin made no mention of the work. Even the communist L’Humanité, which had done more reporting on the destruction of the Basque city than any other French paper, made only glancing reference to the painting. (Picasso’s friend Louis Aragon, a prominent L’Humanité columnist, apparently disliked it so much that he resolved not to mention it, or the artist.)

So how did Guernica become the enduring statement that we know today?

For decades, Picasso scholars have assumed that the artist’s loyal friend Zervos had single-handedly rescued Guernica’s reputation by publishing a special “summer” issue of Cahiers d’Art, his influential art magazine, devoted to the painting. Featuring rapturous appraisals of the work and Maar’s remarkable photographs of Picasso creating it, the issue supposedly circulated throughout the international art world the moment the painting was unveiled. “A powerful defense of Guernica . . . was almost immediately marshaled by the artists, writers, and poets of the Cahiers d’Art circle,” Herschel B. Chipp, one of the painting’s prominent chroniclers, wrote in his classic 1988 account, Picasso’s Guernica. In recent years, other scholars have assumed that Zervos timed the release of the Cahiers d’Art issue for the exact day the Spanish Pavilion opened.

None of this is true. Like other issues of Cahiers d’Art, the Guernica issue is undated, but the magazine’s account books make clear that it was not published until October, a full three months after the painting was unveiled and just days before the Spanish Pavilion closed. For the more than 30 million visitors who visited the Expo that summer, the only mass-circulation publication that wrote in any detail about the painting was the official German guidebook to the fair, produced by the Nazi government. (Designed by Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, the monumental German Pavilion loomed over the low-slung Spanish Pavilion, which occupied a small adjacent plot.) The guidebook ridiculed Picasso’s work as “the dream of a madman, a hodgepodge of body parts that a four-year-old child could have painted.”

As a personal political awakening, Guernica marked an astonishing turn. As a rousing call to defend the Spanish republic, it had utterly failed. When the Expo closed, Guernica did not accompany the pavilion’s Miró mural back to Spain. Instead, it was returned to Picasso’s studio. Its owners apparently didn’t want it. “Does anyone think it won over a single heart to the Spanish cause?” asked Jean-Paul Sartre, who that same summer had published “The Wall,” an acclaimed short story about a Spanish prisoner awaiting execution by a nationalist firing squad. If its reception in Paris, before a huge world audience, had decided its fate, Guernica might have remained little more than a minor footnote in the career of a painter who seemed temperamentally ill-suited for political art.

But Picasso’s friends were not ready to give up. In the fall of 1938, a year after the Expo closed, the surrealist Roland Penrose, who had been to Spain and was deeply involved in the war effort, helped arrange a tour for Guernica in Great Britain to raise funds for victims of the war. Once again, however, it largely failed to connect with the public. “It has had an indisputable moral success,” Penrose told Picasso after the London showing, “but we didn’t have the crowds of visitors I had hoped.”

Still, there was one more chance. Serendipitously, at the time of the British tour, Alfred H. Barr Jr., the first director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art , was nearing the end of a decade-long quest to introduce Americans to Picasso’s art. For years his plans for a huge Picasso exhibition had been stymied because he couldn’t get the paintings he needed from Europe. But now, with the threat of a Nazi invasion, many French collectors were desperate to get their Picassos out of the country: The show was on. And given the circumstances, no work would be more important than Guernica.

With the Spanish republic in desperate straits, though, Picasso was adamant that the painting travel only for fundraising purposes—despite the uninspiring results in Britain. In the end, he agreed to let Barr have Guernica, but insisted that it go first to the Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign, an American advocacy group, to be used in a fundraising tour of four American cities.

As before, however, the tour fell flat with the public. For one thing, by the time Guernica reached the United States, the Spanish republic had already surrendered. But there was also little evidence that Americans were ready for Picasso’s wrenchingly bleak vision of war. The Spanish relief campaign had an impressive roster of sponsors, including Interior Secretary Harold Ickes and writers like Dorothy Parker and Ernest Hemingway. Despite the heavyweight backing, though, the reaction to Guernica was little different than it had been in Paris two years earlier. In L.A., just 735 people came to see it. West Coast papers called it “revolting” and “cuckoo”; in Chicago, it was dismissed as “Bolshevist art controlled by the hand of Moscow”—words that sounded eerily close to the Nazis’ own attacks on modern art. Given that Guernica had been created precisely to protest a Luftwaffe atrocity, Barr realized he would have to work even harder to shape a new understanding of Picasso when his exhibition opened that fall.

On November 15, 1939—two and a half months after the start of a new war in Europe and two and a half years after Guernica’s disastrous Paris debut—Barr’s big show, “Picasso: Forty Years of His Art,” opened in New York. Its centerpiece was the immense, terrifying anti-war painting. It was the show’s culminating work, presented as the sum total of Picasso’s prodigious journey through modern art. Barr had decided to give it a long, gray gallery of its own, carefully illuminated by ceiling fixtures hidden from the viewer, where it could be taken in from a proper distance, in all its apocalyptic splendor.

Up to the last, it was unclear what people would think. Picasso had never done particularly well with the American public. For years, Americans had been hostile to the Paris avant-garde. And just that summer, Guernica had been ridiculed in the press. Yet now, under the cloud of a new world war, Barr’s lucid celebration of the art that Hitler was trying to erase somehow electrified the city. Several thousand people came to the opening night; in the weeks that followed, viewers lined up to get in the museum in numbers that smashed all previous records for a living artist. “COLOSSAL SUCCESS 60,000 VISITORS SURPASSING VAN GOGH” Barr cabled Picasso after the first few weeks. Soon, more than a dozen other museums were clamoring to host the paintings. And because it was too dangerous to return any of them—including Guernica—to Europe, they mostly got their way. Crisscrossing the country, the show went on to Chicago, St. Louis, and New Orleans, among many other cities; in San Francisco, it was so popular that hundreds of visitors refused to leave the museum on the final day of its run.

Here was Guernica’s true debut. The war that provoked it had already been lost, but another, more urgent one was just beginning. It was in Barr’s New York show—not the Paris Expo in 1937 or any of the Spanish relief shows that had come after it—that Guernica was finally recognized as a definitive statement about the horrors of war and the freedoms that were now being brutally crushed on the continent. As Barr put it, “Picasso has spoken of world catastrophe in a language not immediately intelligible to ordinary man.”

This article was adapted from Hugh Eakin’s recent book, Picasso’s War.