Big Oil’s run of record profit will suffer only a minor dent for the third quarter, even as the global economy shows signs of cracking under the pressure of rising inflation and interest rates.

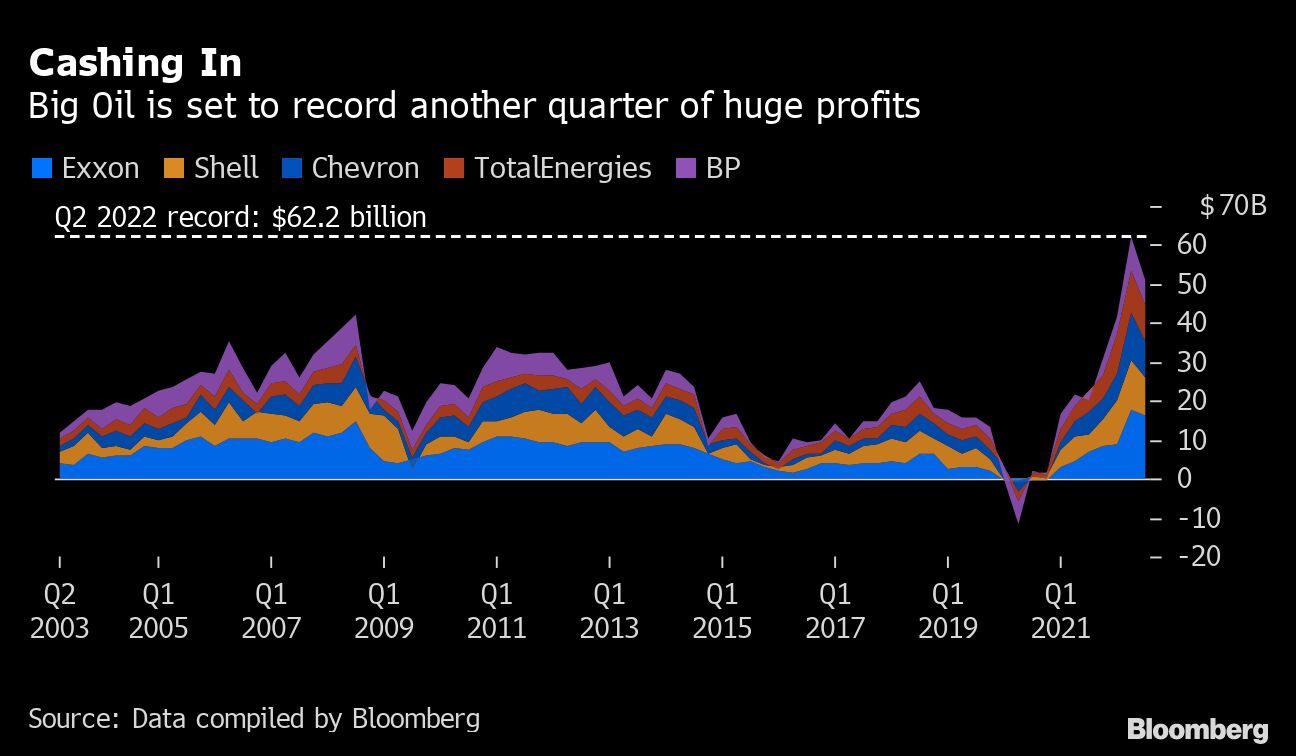

Indications of the slowdown will be evident across their sprawling businesses, from lower crude prices to slumping chemicals margins. Yet the five oil supermajors are still poised to report the second-highest earnings since their formation in the early 2000s, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

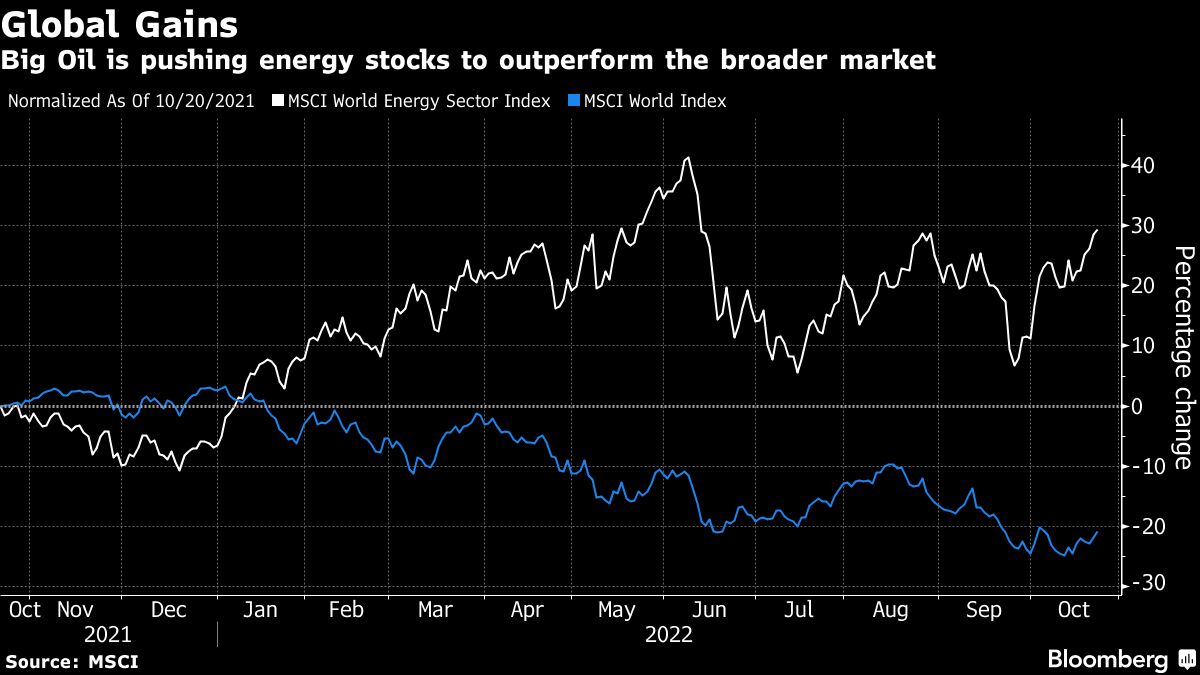

A modest decline in earnings after record profits earlier this year won’t be enough to take the industry out of the political cross-hairs. As governments around the world grapple with both the cost of energy today and the need to transition to cleaner alternatives in the future, the risk of state intervention remains.

“It’s definitely awkward,” said Abhi Rajendran, adjunct research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. “These companies won’t want to be beating their chest over strong business results that are coming at the expense of consumers and a difficult economic environment.”

Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp., Shell Plc, TotalEnergies SE and BP Plc will report combined earnings of $50.7 billion in the third quarter, down from the second quarter’s record of more than $62 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

“It’s a slightly weaker environment than last quarter, but in the context of the last 10 to 15 years, the results will be extremely strong,” said Biraj Borkhataria, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets. As the wider economy slows, the oil and gas industry “is one of the few areas where earnings are going to be resilient.”

Gas vs Chemicals

Preliminary third-quarter figures released by Shell and Exxon give an indication of which parts of the industry are up and which are down.

The Texas oil giant said earlier this month that earnings from refining and chemicals will be lower. Morgan Stanley expects Exxon’s refined products and chemical earnings to drop about 35% from the second quarter, and says the weakness will be replicated by others. The banks sees Chevron’s downstream earnings 45% below the prior three months.

It was a similar picture from Shell, which reported a decline in refining and a negative margin of $27 per metric ton from chemicals. That reflects a broader economic slowdown, particularly in Europe, as high natural gas prices force some industries to curtail production.

“Chemicals are closely intertwined with the economy,” said Columbia’s Rajendran, who is also director of research and advisory at Energy Intelligence. “It says something about the health of the economy.”

On the flip-side, analysts revised up their earnings estimates from natural gas after Exxon’s trading statement, which showed the company benefiting from higher prices in the period, offsetting the decline in crude.

This is good news for shareholders, but could add to political pressure on the companies. The UK already slapped a windfall tax on oil and gas producers earlier this year, and the European Union proposed its own levy in September. Shell Chief Executive Officer Ben van Beurden, who retires at the end of the year, said recently that energy companies would need to pay more tax to help governments shield their poorest people from energy bills.

In the US, President Joe Biden last week called on energy companies to plow their gains into fresh production rather than giving more cash to shareholders. “You should not be using your profits to buy back stock or for dividends,” he said at the White House. “Not now, not while a war is raging.”

It’s unlikely that Exxon and Chevron will accede to Biden’s request, although they may not continue with the repeated dividend and buyback hikes seen over the past year, according to Paul Cheng, a New York-based analyst at Scotiabank. The US giants are likely “very comfortable” with their recently-increased buybacks, each worth about $15 billion a year, he said. The European majors are more likely to accelerate shareholder returns, according to Cheng.

In the past, the oil majors have indeed invested in new production during boom times, but those high spending decisions have too often come back to bite them when prices declined. Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered the current energy crisis, companies were also under pressure to curb spending on fossil fuels and pivot to low-carbon technologies, rather than spend their cash on costly megaprojects.

With record profits this year, companies are still showing spending restraint, said Oswald Clint, an analyst at Sanford C Bernstein Ltd. “We should always be careful to say this time is different, but certainly it smells different this time,” he said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.