Japan says it’s the last chance to reverse the trend of its declining birthrate.

The poster child for aging society is nearing a “whatever it takes” moment on spending to boost the number of babies born each year. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is promising steps that will be on a “different dimension” to those attempted so far. Kishida has pledged to double the amount of money on programs to support children, which would take outlays to 4% of gross domestic product. Steps such as a bigger allowance for families are welcome, but will more spending actually make a dent in the fertility crisis?

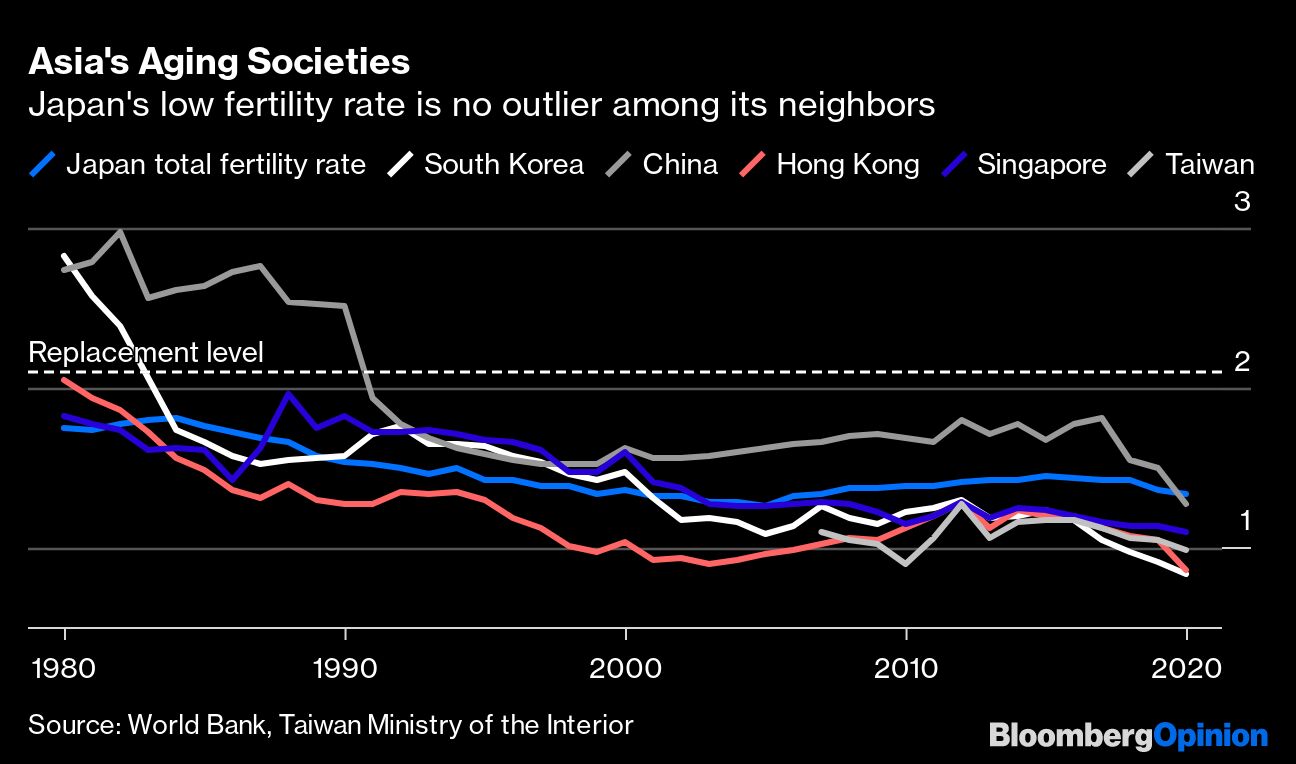

It’s easy to be fatalistic about the prospects. But if Japan is destined to become an older, smaller society, it won’t be alone. Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike declared last week that the declining population was a “national challenge.” While she meant that it’s not an issue merely for the capital, her language is wide of the mark — it’s an international challenge. The increasing level of desperation in the rhetoric of Tokyo’s politicians will soon be heard in other countries, if it isn’t already.

Reporting on Japan’s declining number of kids has for decades latched onto to simplistic arguments to explain the trend — from overwork at the office to outdated gender stereotypes. This attitude is best exemplified in the 2013 documentary “No Sex Please, We’re Japanese,” in which supposed dysfunctional relationships in the bedroom are given as the main reason for the declining population. Fast forward a decade, and suddenly we’re seeing the same thing happen in Western bedrooms, too.

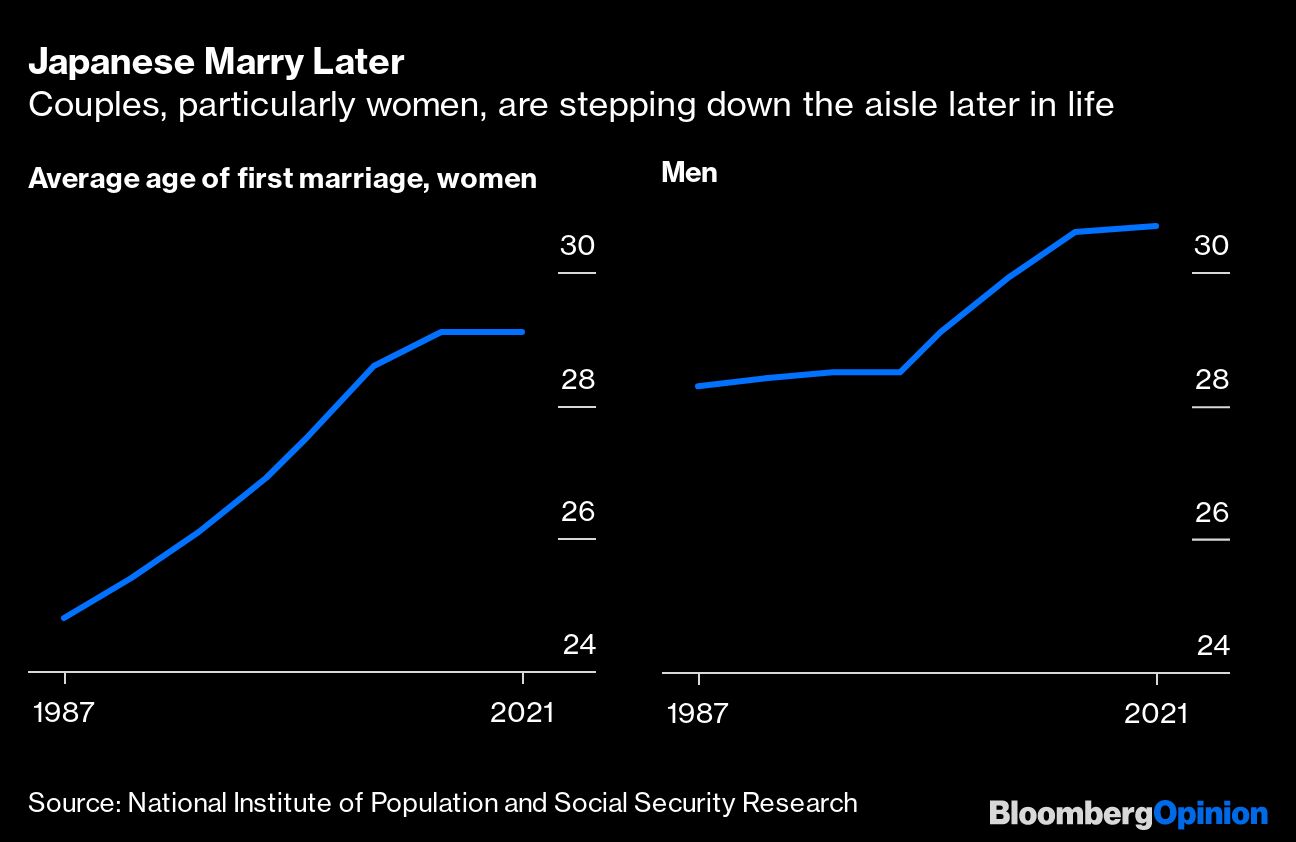

Policymakers need to take a more sober look at the issue. As elsewhere, officials in Tokyo will struggle to overcome two hard trends. The first is that the average age that women marry at has risen from 25 in 1987 to 29 in 2021, delaying their first child and leaving fewer fertile years. While spending on in-vitro fertilization, as well as making it easier to have children outside of marriage, can help, they are unlikely to change the trend.

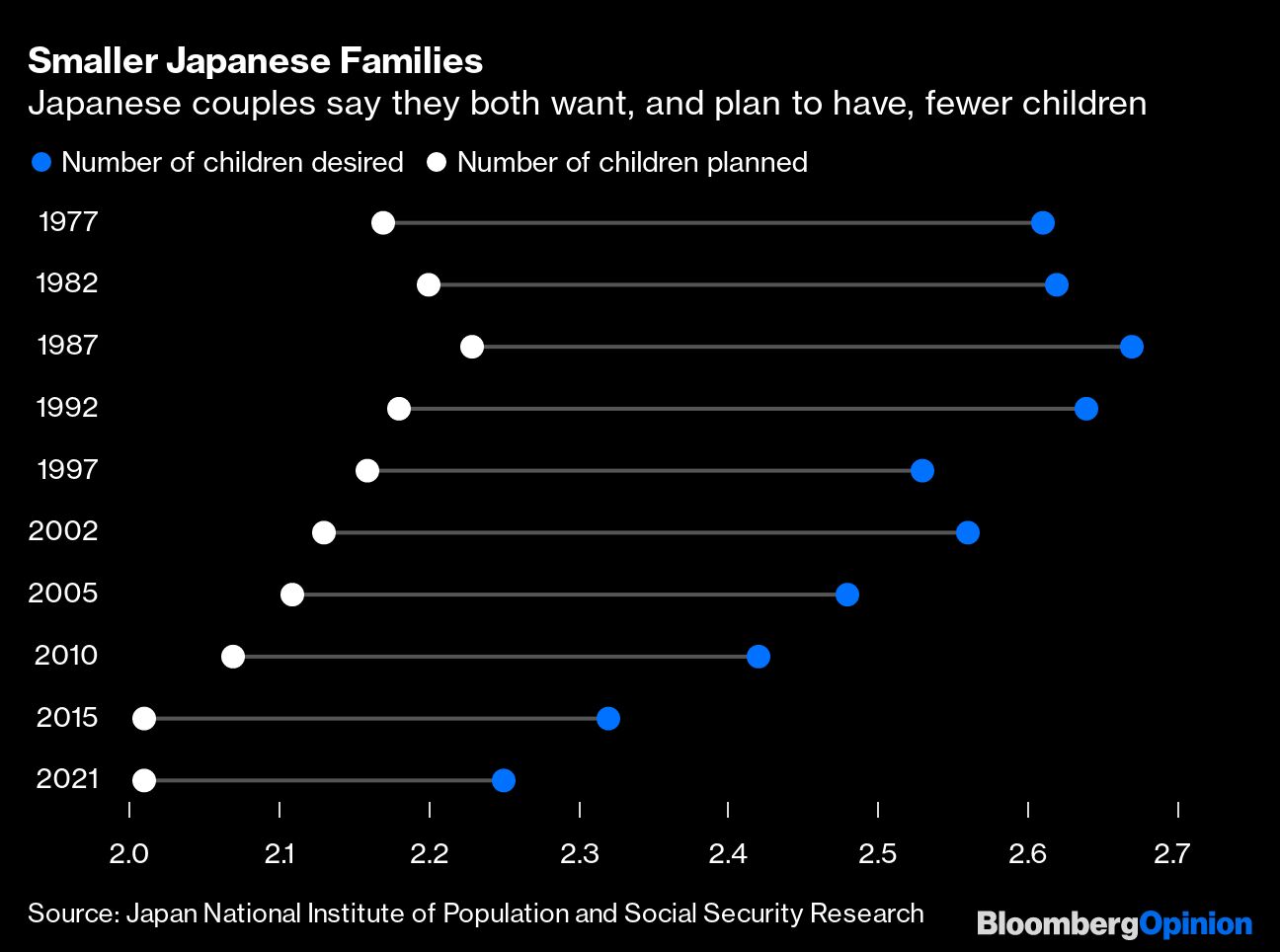

The other is that married couples increasingly say they want fewer kids. In a survey in 2021 they said they plan to have an average of 2.01 offspring, a little under the 2.25 average they would ideally have. Both figures have been declining for years, along with the gap between them; in 1977, couples said they wanted an average of 2.61 kids and planned for 2.17.

If most couples only plan for two children, it’s easy to see how the national average is quickly reduced when added to those who don’t want, can’t or otherwise end up not having kids. Modern lifestyles and intense competition for schools, jobs and success in a world that’s increasingly cut-throat has made raising families more work than ever. Parents are increasingly incentivized to dedicate more of their efforts to ensuring the next generation has every chance of success, ferrying their offspring to piano recitals, supplementary classes or gymnastics lessons. Academics refer to this as the “quantity-quality trade-off,” in which parents choose to invest more money and time in fewer kids.

And it’s not just a matter of money. A Cabinet Office survey in 2014 found that across almost every category of education, employment or wealth, a majority favored having two kids. Almost the sole exception were couples who live with the husband’s parents (a not uncommon arrangement, though decreasingly so), who wanted three. Demonstrating the inverse relationship between wealth and reproduction, those in the lowest income bracket were the most likely to want three children.

Kishida can create money. But he can’t create time. While access to childcare is a relief to overworked parents, outsourcing doesn’t look to be the solution, either. In Singapore, one in six households employs a domestic helper, yet its fertility rate trails even Japan’s. As an International Monetary Fund report notes, the city-state’s low fertility rate despite childcare access “suggest that formal sector provision cannot substitute for parents’ spending quality time with children.”

Perhaps if the gender imbalance was addressed? Neighboring Taiwan hails itself as the most gender equal society in Asia, but also trails Japan. If the economy was doing better, and households had more to spend? South Korea’s per-capita GDP has already surpassed its neighbor, but at 0.81 it now has the world’s lowest fertility rate.

It’s a worldwide phenomenon, one that correlates strongly with wealth and increased opportunity for women. US fertility is already well below replacement levels, along with every country in the European Union — even those that strongly favor immigration. We have seen how authoritarian regimes such as China have managed to suppress the birthrate through policy. But in a democracy, can government action turn the trend in the other direction?

Some point to the example of Hungary, which at 5.5% of GDP already spends more on family support measures than Tokyo plans to. Hungary is unusual in that it has seen an increase in the fertility rate over the past decade, but it’s far from clear how much of that is due to policy. It’s also notable that the European Parliament no longer considers Hungary a full democracy, while the country is also taking regressive steps, such as tightening abortion rules, that might improve its numbers.

Japan, and the countries that inevitably go down the same path, cannot just hope to happen upon an unlikely policy cure-all that will restore fertility to baby-boomer levels. Spending should focus on preparing society for changes now inevitable — whether that’s in immigration to ease the decline in the labor force, or concentrating policy on helping those families who do desire children have as many as they want. The choice need not be one between natalism and fatalism.

More from Bloomberg Opinion:

- Demography Is Coming for Us, Too: Eduardo Porter

- Have You Calculated How Much a Child Will Cost?: Erin Lowry

- Japan’s Fertility Crisis Is Your Problem, Too: Gearoid Reidy

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Gearoid Reidy is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Japan and the Koreas. He previously led the breaking news team in North Asia, and was the Tokyo deputy bureau chief.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.