Everybody loves trees. They're good for all sorts of things. According to a 2019 study published in the journal Plants People Planet, trees can get rid of air pollution, reduce stress, and promote a feeling of community. They can also reduce rising urban temperatures, provide shelter for local animals, and manage stormwater in the area. It's no wonder that reforestation has become a go-to choice for corporations making pledges to become carbon neutral by mid-century.

"The overwhelming evidence from the scientific literature suggests that investing in trees is [...] ultimately an investment for a better world," wrote the study's authors.

However, although nature is open to all, it's not necessarily accessible to all.

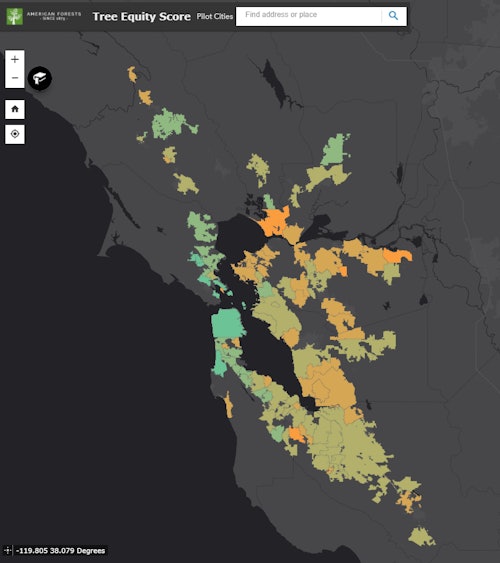

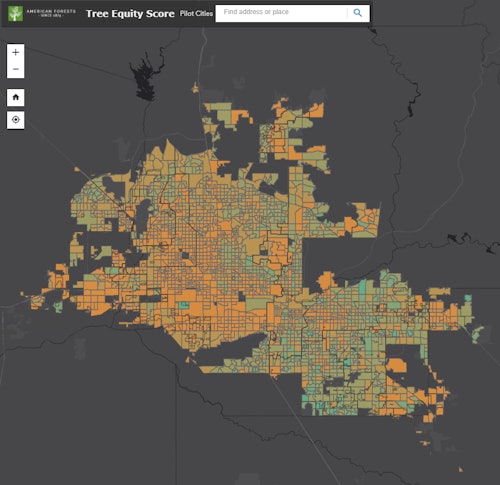

A non-profit conservation group called American Forests is looking to fix this problem by creating a "Tree Equity Score" for cities. The score is obtained through calculations based on satellite imagery of tree canopy cover, estimates of the population, and census data on income levels. Then a priority is assigned based on the demographics of the location's residents, including race, income, age, and urban heat island severity.

The resulting score will show which areas should be prioritized for tree planting.

"A map of tree cover in virtually any city in America is also effectively a map of income and race," Jad Daley, CEO and president of the organization, told Grist. Lower income neighborhoods have less trees compared to higher income areas. This means that vulnerable communities, groups that suffer more from the effects of climate change and air pollution, are being neglected when they're the demographic that could benefit the most from trees.

A pilot program has already been launched in three areas: Rhode Island, Maricopa County in Arizona, and the San Francisco Bay area in California. Places in green don't need as many trees. Neighborhoods that are orange are spots that desperately need more trees. American Forests' goal is to eventually have all urban areas mapped in the U.S. by 2022.

Why are poorer neighborhoods less likely to have trees? Redlining, a practice that discouraged government and capital investment in communities of color, is the primary reason, according to a 2020 study.

"Our cities are not like tropical rainforests that developed on their own," Sarah Lillie Anderson, senior manager of tree equity for American Forests, explained in a company blog entry. "People designed cities. And, unfortunately, they did not factor in the needs of everybody when doing so. The design process was far from inclusive."

American Forests believes that simply planting trees doesn't help if you're not putting them in places where they'd help the most. "It's not just that cities need more trees," Daley told Grist. "They need trees in the right places."

By referring to the Tree Equity Score, they hope that cities will be able to easily see where they need to fill the gap in underserved areas. "If your goal is health equity, if your goal is climate justice," Daley told the site, "this is a roadmap that is going to get you there."