Investors and Wall Street analysts are sounding the alarm about a possible “market accident”, as successive bouts of tumult in US stocks and bonds and a surging dollar cause rising levels of stress in the financial system.

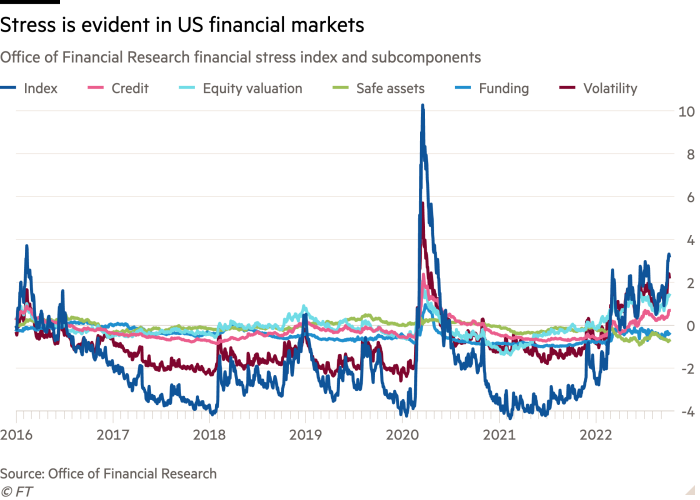

A gauge of strain in US markets — produced by the Treasury’s Office of Financial Research — has soared to its highest level since the coronavirus pandemic ructions of May 2020.

Even as equities on Wall Street start the new quarter with gains, the OFR’s Financial Stress index is near a two-year high at 3.1, where zero denotes normal market functioning. That has added to a growing list of benchmarks which suggest trading conditions in US government debt, corporate bonds and money markets are increasingly stretched.

“The velocity of things breaking around the world . . . is obviously a ‘neon swan’ telling us that we are clearly now in the market accident stage,” said Charlie McElligott, a strategist at Nomura.

Rising concerns have been fuelled by a series of big interest rate increases by the Federal Reserve to curb inflation. Higher borrowing costs and fears of an economic slowdown have led a steep sell-off in public markets, while strengthening the US currency to the detriment of its global peers.

Rate rises by the European Central Bank and the Bank of England — as well as aborted tax plans by the UK government — have also amplified swings in the market this year as global policymakers attempt to rein in price growth.

“When financial conditions tighten this much, everyone is looking for who or what will be the cause for central banks to blink,” said Michael Edwards, the deputy chief investment officer of hedge fund Weiss Multi-Strategy Advisers. “They [the Fed] are determined to get financial conditions tighter, and [because] the economy is very strong . . . they have to use funding markets as the transmission mechanism. So someone will get hurt.”

McElligott pointed to the 20 per cent slide in the Japanese yen this year, a sell-off in British sovereign debt in recent weeks, and a smattering of loans stuck on banks’ balance sheets that lenders are unable to offload to investors even with deep discounts, as signs of the strains in markets.

He added that the strength of the dollar was “causing tremendous strains economically . . . and increasingly, metastasising in markets”.

The stresses mean that markets are not operating as they should: companies aren’t easily able to obtain funding, it is harder to buy and sell securities, prices are volatile and investors are less willing to take on risk.

Conditions have been deteriorating all year, but until late it has been evident primarily in the stock market where valuations have dropped precipitously as borrowing costs have risen and the prospects of growth have been slashed.

Private companies have been unable to list their shares publicly and banks have had to withdraw planned debt financings for their clients after investors refused to open their cheque books.

Last month banks were forced to hold $6.5bn of debt to fund the buyout of software maker Citrix on their own balance sheets after they failed to find willing buyers for the entirety of the debt financing.

“This is a story about boiling lobsters. You put them in cold water and slowly turn the heat up,” said George Goncalves, head of US macro strategy at MUFG. “That is what is happening in markets. The Fed is turning up the heat. But because the market is still flush with liquidity, it’s not yet clear where the weakness is.”

JPMorgan Chase economist Bruce Kasman on Friday said that the relative health of the banking system and small financing needs for much of the corporate world meant the vulnerabilities to the financial system remained low. However, the US bank warned that the increase in the OFR’s index is evidence of the broader spread of stress throughout financial markets — and decreased appetite for risk — wrought by the strong dollar and higher US interest rates.

“Risks to global financial stability are an increasingly known unknown for the outlook,” Kasman said.

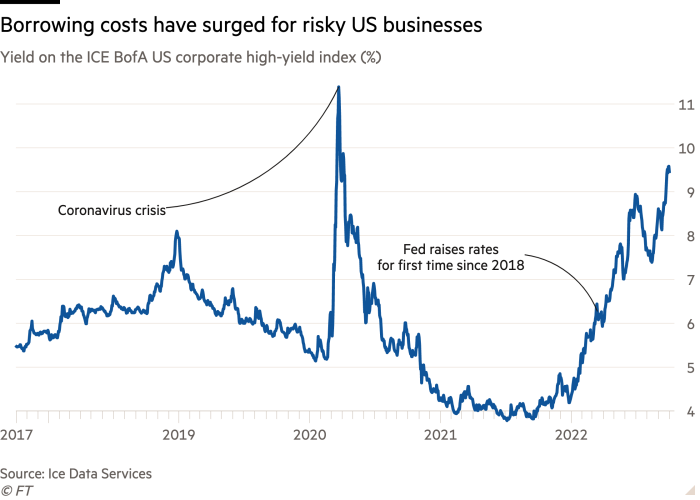

The corporate bond market is also showing increasing signs of strain, according to Marty Fridson, chief investment officer at Lehmann, Livian, Fridson Advisors.

Fridson noted that the premium investors demanded to hold risky, junk-rated corporate debt over haven Treasuries has increased significantly over the past month. By his calculations, the junk bond market now reflects a 22 per cent chance of recession, up from just 2 per cent in mid-September.

Corporate defaults more than doubled from July to August, according to rating agency Moody’s. Strategists with Bank of America warned on Friday that their gauge measuring stress in the credit market was at a “borderline critical level” and that “market dysfunction starts” if it rises much further.

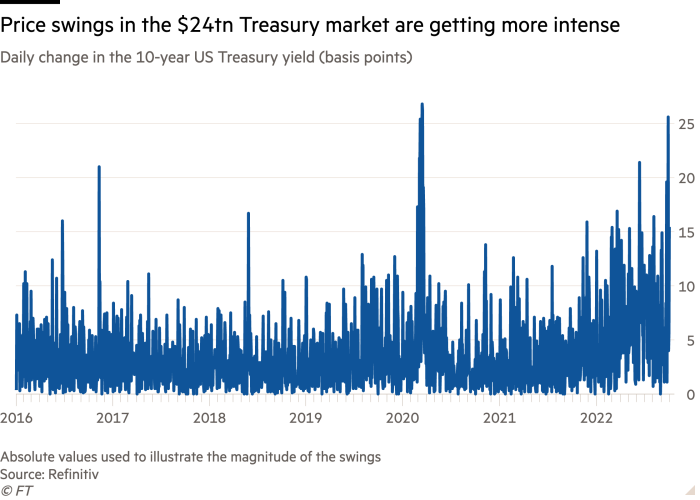

Separately, a Goldman Sachs index that measures market impairments and dislocations is being driven higher by stress in funding markets as well as heightened volatility in the $24tn US government debt market.

The 10-year Treasury yield, which is a benchmark for borrowing costs worldwide, has risen this year from about 1.5 per cent to 3.6 per cent — and last week it briefly breached 4 per cent for the first time in 12 years.

Volatility in that market has also reached the highest level since the coronavirus-induced ructions of 2020, according to the Ice BofA Move index.

The volatility can also be seen on a day-to-day basis: the biggest move in the 10-year Treasury in 2021 was a 0.16 percentage point drop on November 26. There have been seven days so far this year with bigger moves.

While policymakers at the Fed remain steadfast in raising rates, they too are on the lookout for potential dangers from the market drawdown.

“As monetary policy tightens globally to combat high inflation, it is important to consider how cross-border spillovers and spillbacks might interact with financial vulnerabilities,” Lael Brainard, the Fed’s vice-chair, said on Friday. “We are attentive to financial vulnerabilities that could be exacerbated by the advent of additional adverse shocks.”