Young voters feeling left behind by runaway home prices and anemic wage growth are set to become the decisive force in South Korea’s presidential elections on Wednesday.

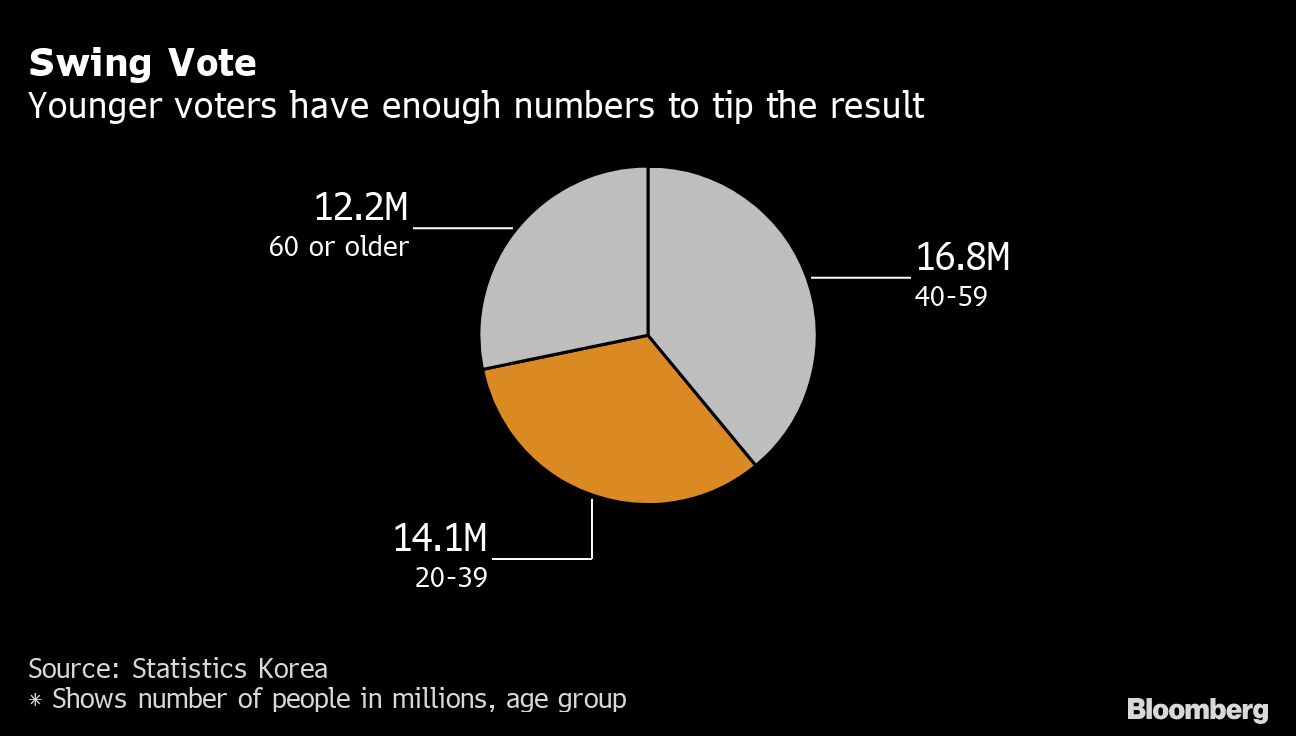

Financially battered by the pandemic, people in their 20s and 30s have emerged as the biggest block of swing voters in the race with fewer precedents for how they will vote compared with older generations in the world’s fastest-aging nation.

Both Lee Jae-myung of the ruling Democratic Party and Yoon Suk-yeol of the People Power Party see the potential for swinging the election with the support of younger people and the danger of losing it if they don’t engage sufficiently.

The two main rivals are reaching out to YouTubers, routinely unveiling campaign pledges via Instagram and even using deepfake technology to deploy artificial-intelligence versions of themselves in the hope of impressing the younger, tech-savvy generation.

For Kim Min-jeong, a 25-year-old makeup artist in Seoul, none of these efforts matter when real estate prices have shot up so “absurdly.” Kim is certain that she and her boyfriend won’t be able to afford a house on their own if they get married.

That kind of frustration suggests the risk of losing the younger vote is larger for Lee as the representative of the ruling party and the status quo.

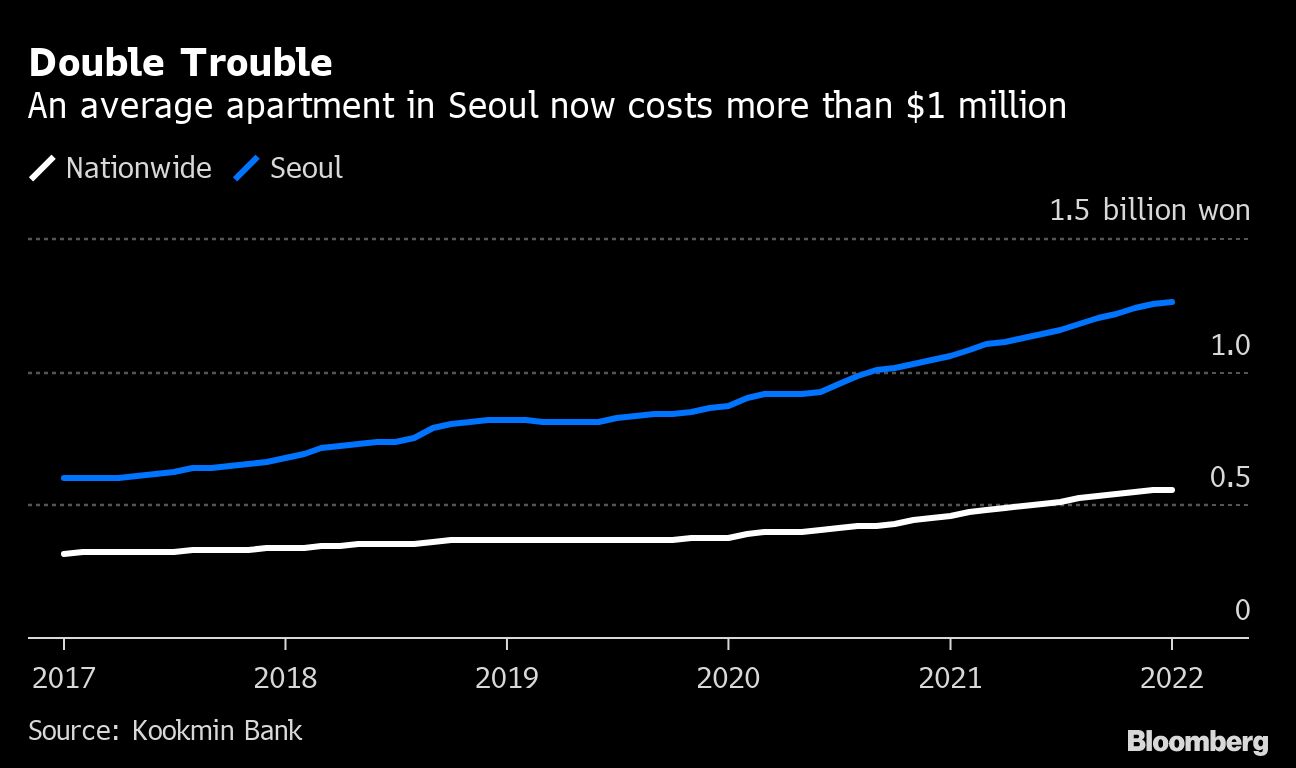

In the last five years alone, the average price of an apartment in Seoul has doubled to reach more than a million dollars, while a wave of price escalation is palpable across the country.

“It’s now better to live alone than struggle together, my friends say,” she said. “There’s no room for hope. Not even for fairy tales.”

Kang Mi-hyun, a 23-year-old university senior, feels the main candidates lack a genuine understanding of the jobs situation facing younger voters.

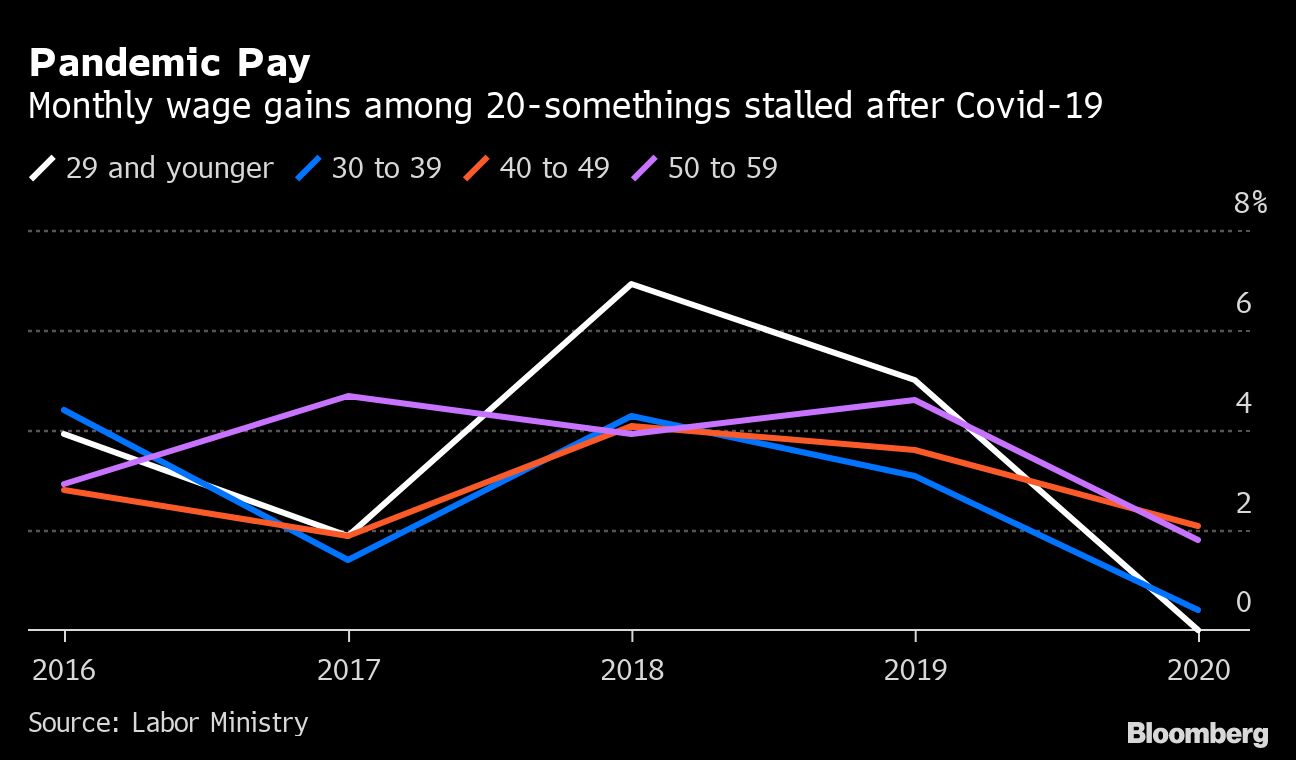

Wages remain so chronically suppressed it now makes more sense to settle for a lower-paying job than stay unemployed and risk waiting for a job that may never come, she said.

At this point, even a perk such as free coffee might be enough to prompt people to take positions they don’t want, she said.

Lee’s universal income proposal has failed to resonate as much as expected with people like Kang. A January poll showed that a majority of people in their twenties and thirties disagreed with the idea of blanket income support.

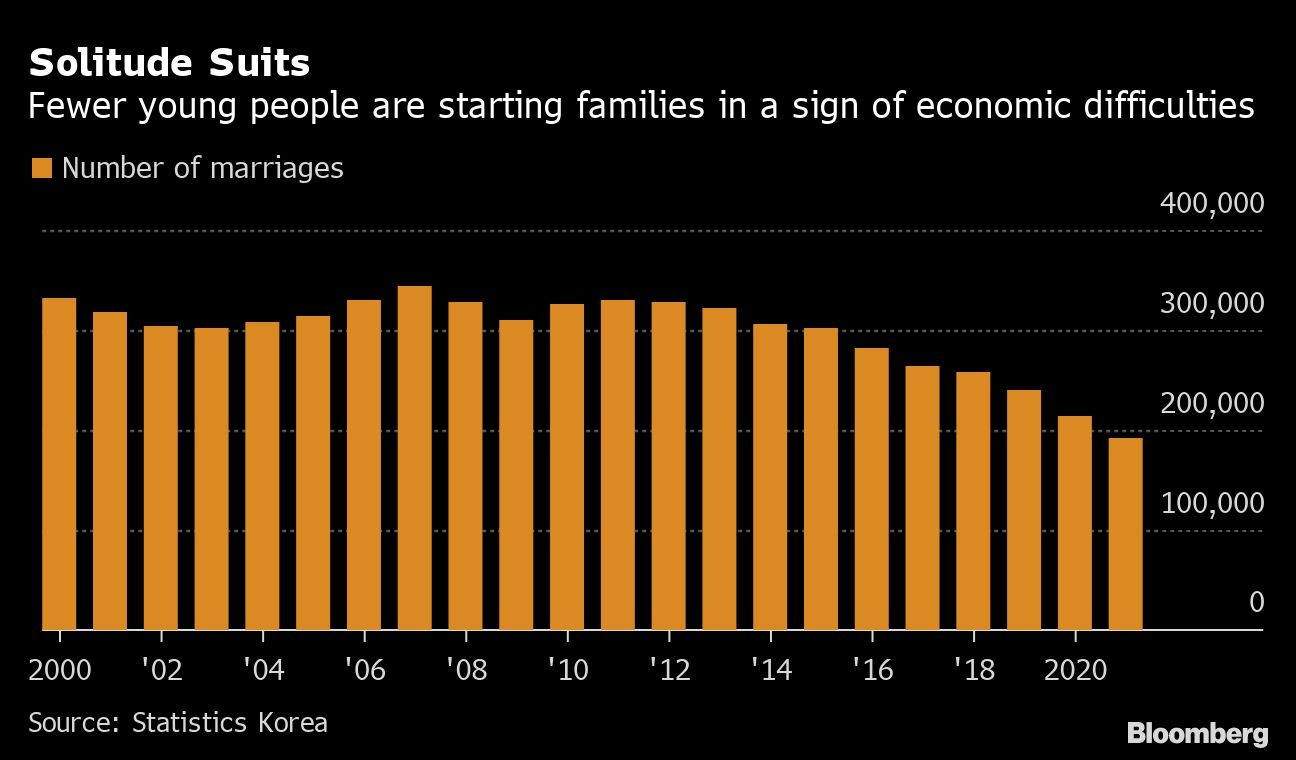

Still, the pandemic has largely wiped out wage growth for the under-30s, adding to the reasons why more people are putting off, or giving up on marriage. That is pushing the world’s lowest fertility rate down each year.

The decline was already accelerating before Covid-19 made it harder for people to meet, date and wed.

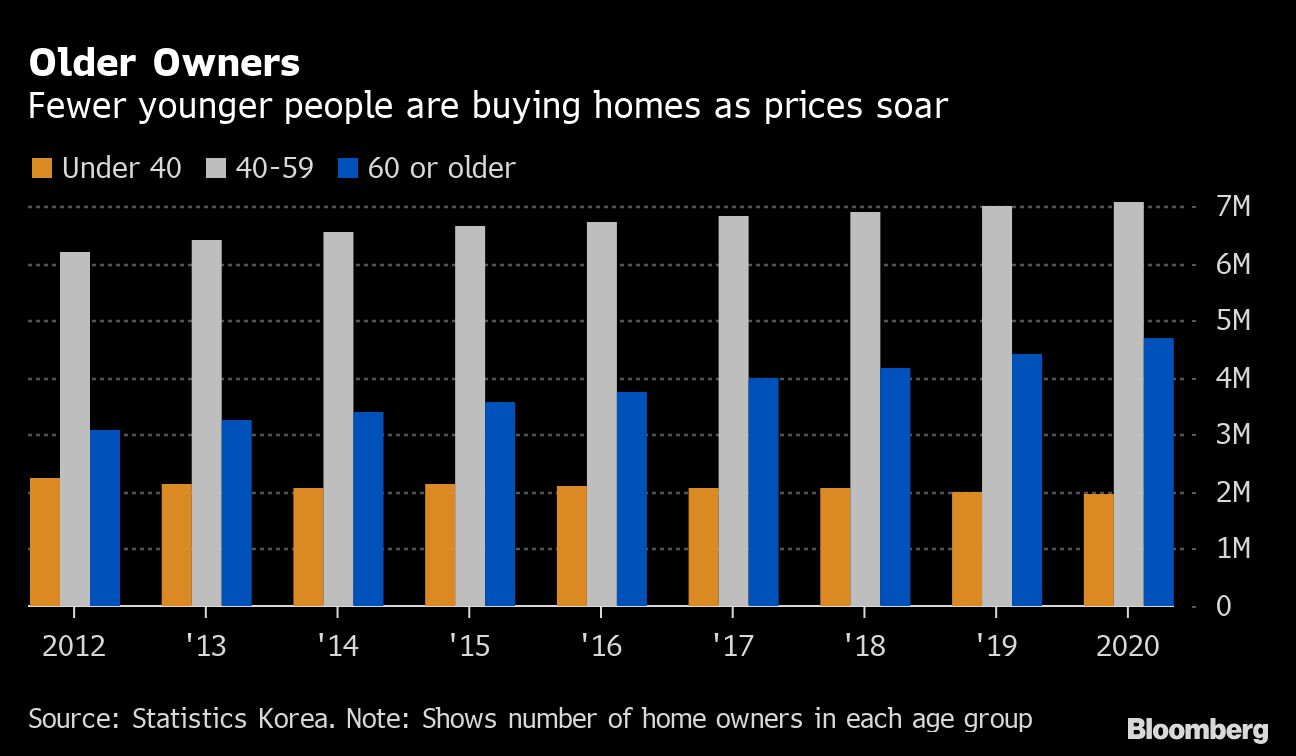

With fewer new families and slower wage growth, the share of home ownership among young people has also been shrinking.

In contrast, middle-aged and older citizens are snapping up more homes each year, with many relying on credit that is driving up household debt to record levels -- and apartment prices along with it.

“The gap between those who own a home and those who don’t has widened enormously and the sense of deprivation is huge among those who don’t,” said Jeong Keun-sik, professor of sociology at Seoul National University. “The property issue has aggravated the problem facing the give-up generation.”

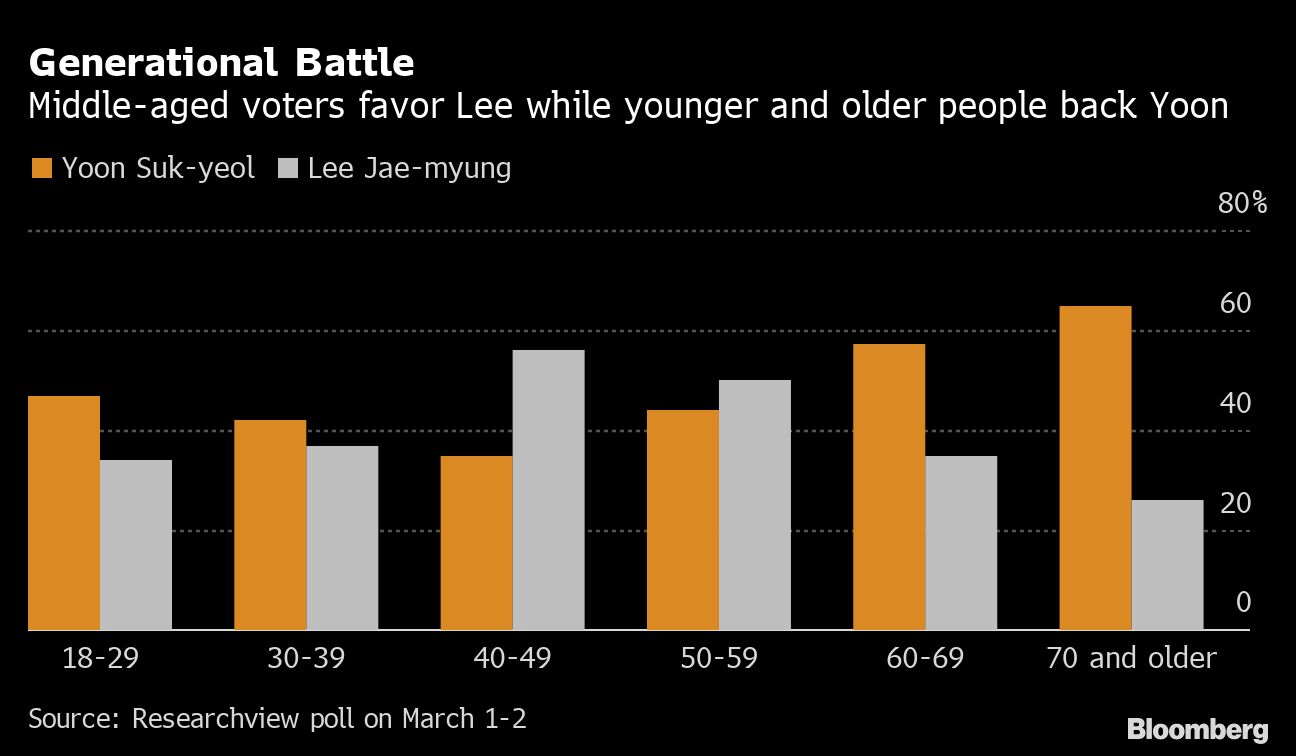

So far younger voters are more likely to side with Yoon than Lee, giving the opposition candidate a slight lead whereas middle-aged groups remain the mainstay of support for the ruling party candidate.

“The issues of housing and jobs have triggered the feeling in young people that they aren’t being taken care of and that the government should be held responsible,” says Lee Hyeon-Woo, political science professor at Sogang University in Seoul. “Their anxiety about the future is what’s driving them.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.