At first glance, Noha looks like a frail toddler drowning in a pair of brightly coloured pyjamas that belong to an older sibling.

But the Yemeni girl is actually seven years old and so starved that her organs have begun shutting down one by one.

Noha is among an estimated 2.4 million children in war-torn Yemen that the United Nations fears will be pushed to the brink of starvation by the end of the year, because of the conflict and unprecedented shortages in humanitarian funding during the pandemic.

Like many, Noha is suffering from a deadly mix of afflictions. She has rickets, limb spasms and convulsions due to calcium deficiency, according to Yemeni doctor Ashwaq Muharram, who is helping to treat her.

“She looks like a starved baby – not a child,” Muharram tells The Independent from Hodeidah, home to some 300,000 people.

Noha’s flesh is drawn tight across her skull. Without assistance, she struggles to sit up on her hospital bed, which nurses have strewn with Disney bedsheets to cheer her up.

Earlier this month, when she was finally brought into Thawra hospital in Hodeidah, a coastal city among the worst hit by Yemen’s hunger crisis, medics feared she would not make it.

Her family say they had to wait until the last minute because they had no money to pay for transport to a hospital or any treatment.

“Mostly we eat bread, and some rice donated from friends or a charity. We never have any protein,” says Noha’s mother, who also appears malnourished and frail. They can only very occasionally get hold of vegetables like tomatoes.

“We have had no money coming in because of the war and the restrictions imposed because of the coronavirus, so we cannot afford to eat,” says the mother, who asks that her name not be published.

The whole family is going hungry, but became increasingly alarmed when Noha started suffering from diarrhoea that left her severely dehydrated and malnourished.

“A basic basket of goods costs over $45 now (£34), which is a month’s salary that we haven’t had in years,” the mother continues.

“We do not have enough money to feed any of the children properly.”

A gynaecologist by trade, Muharram has for years been running a mobile nutrition clinic from the back of her car that tours the more remote areas of Hodeidah.

Despite a critical lack of medicine and doctors, Hodeidah’s Thawra hospital is treating several critical cases, having long been the front line of Yemen’s five-year war. The city is among the hardest-hit by soaring food prices, as well as diseases such as cholera, which only exacerbates malnutrition cases.

“The situation was already terrible because of the war but made worse by the coronavirus, which has meant any work [people had] has now halted,” she tells The Independent.

Before the pandemic reached Yemen’s shores, more than 15 million people – over half the country’s total population – were already relying on humanitarian food aid to survive, according to the UN.

The arrival of Covid-19, which shuttered businesses and disrupted supply lines, has only made that hunger crisis more acute.

Vanessa Roy, from Famine Early Warning Systems Network, tells The Independent that 2020 could be a record bad year for hunger in Yemen.

“This year will be the worst in terms of the total population anticipated to be in need of food aid,” she says.

This week, the UN sounded the alarm about another potential famine.

Speaking to the Security Council on Tuesday, the UN’s humanitarian chief, Mark Lowcock, said that without more funding and an immediate ceasefire, there would be a surge in hunger, malnutrition, cholera, the coronavirus and “above all, death”.

Despite the fact the country is on “the verge of collapse”, he said the UN was only able to raise 18 per cent of the money needed to run their programmes this year after a failed funding drive.

They have already had to close vital programmes, including those treating malnourished children like Noha.

Just a few days before Lowcock’s statement, several UN agencies said that an additional 1.2 million people in the largely government-held south of Yemen will be acutely food insecure by the end of the year.

The joint report describes how Yemen is in the eye of a “perfect storm” of economic shocks, conflict, floods, a plague of desert locusts – and now the coronavirus.

“We are witnessing a very alarming deterioration and we don’t see anything allowing us to stop this current decline,” Annabel Symington, a spokesperson for the UN’s World Food Programme, tells The Independent.

“We need to act now, or it will be too late”.

Yemen has been ravaged by a ruinous civil war since the Iran-backed Houthi rebels swept control of the north of the country in late 2014, ousting the president, Abedrabbo Mansour Hadi.

In response, Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies launched a bombing campaign in March 2015 to try to reinstate the internationally recognised government.

Five years on, there is little hope of an end to the fighting. Adding to the country’s multitude of woes, a second civil conflict has erupted within the anti-Houthi alliance between the southern separatists and the recognised Yemeni government.

In this tornado of violence, the country was ill-equipped to deal with the arrival of the coronavirus, which has infected at least 1,700 people and killed almost 500 more, according to official figures. A lack of testing means the real numbers are expected to be far greater.

But experts fear that, while the deadly virus has piled immense pressure on Yemen’s crumbling healthcare system, hunger may still be the biggest threat to civilians.

In fact, Oxfam says that more people in Yemen may die this year from hunger linked to Covid-19 than from the disease itself.

Soaring food prices are among the main reasons for hunger in Yemen. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) told The Independent that the cost of staples such as flour has increased by 40 per cent since last year alone, while the cost of food in general has tripled since the start of the war.

This is driven in part by a sharp decline in food and aid coming into Yemen, a country that relies on imports for 90 per cent of its supplies.

But there are other factors piling pressure on families.

New reports shared with The Independentindicate that the destruction of Yemen’s agricultural sector, which employs half the country’s workforce and is responsible for 15 per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP), will also push more people into food insecurity this year.

The FAO said last week that cereal production this year is forecast to be just 365,000 metric tonnes – less than half of pre-war levels.

The crops that are among the hardest hit are the country’s palm trees. According to public reports and local journalists investigating the issue, half the country’s more than 4 million palms have died since the start of the war.

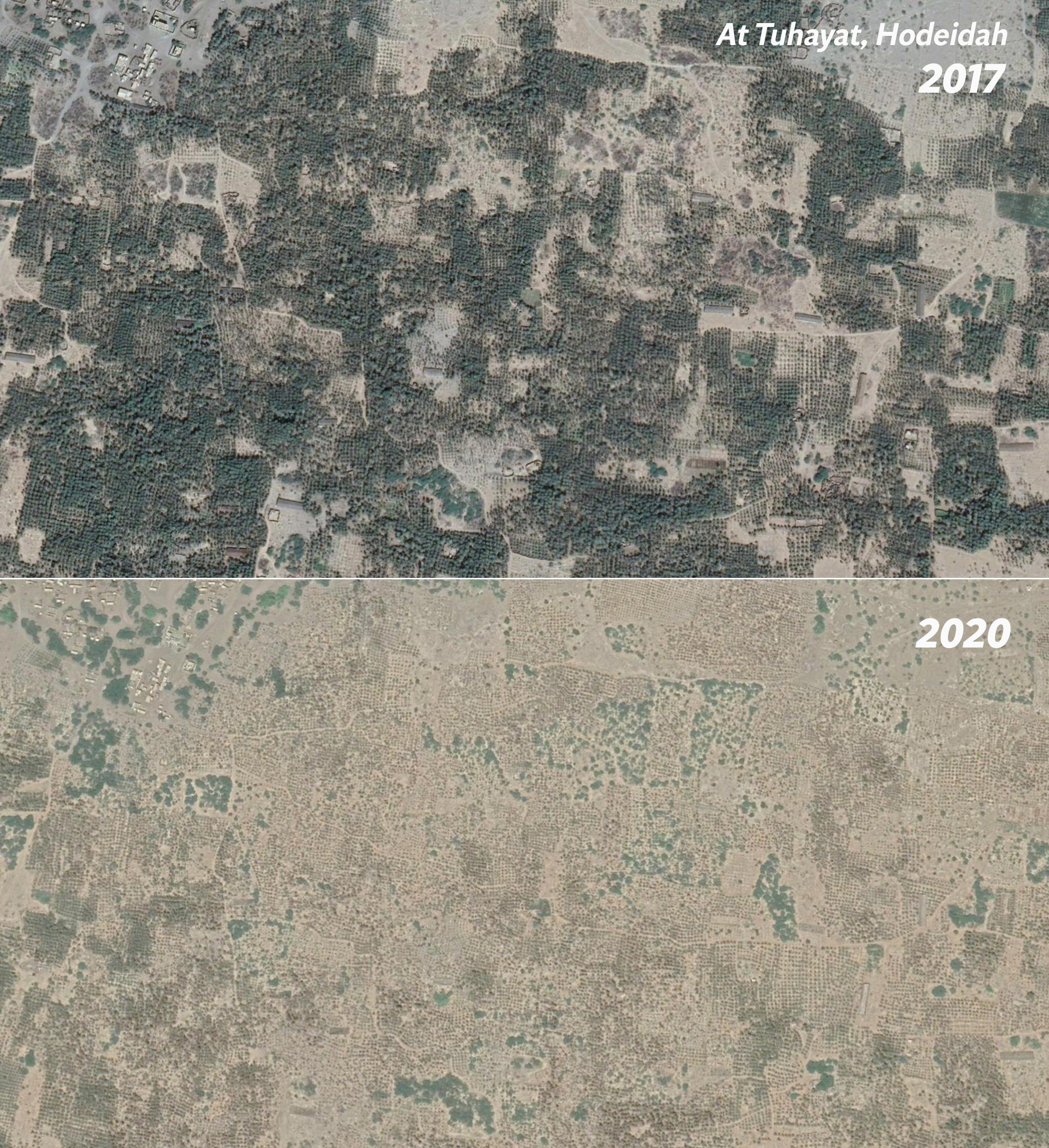

In Hodeidah alone, the agricultural hub where Noha lives, a million fruit palms are believed to have died over the last five years, devastation tracked by Bellingcat and Dutch peace organisation Pax using satellite imagery.

“We found that in the three locations, date palms have been disappearing over the last three years. In certain areas, more than half can be seen on the satellite imagery to have dried out,” says Wim Zwijnenburg, the author of the report.

He explains that attacks on farms and water sources, combatants’ land-mining plantations, as well as drought and a lack of fuel to power water pumps have all ravaged the area.

“It shows you the secondary impact of conflict on food security. Date palms are just one aspect. There is a loss of agricultural yields across Yemen over the last five years”.

The Yemen Data Project, which tracks airstrikes in the country, told The Independent that since the start of the war there have been over 680 air raids on farmlands across the country, killing and injuring nearly 400 civilians, and disrupting agricultural production. At least 153 of those strikes have battered farms in Hodeidah alone.

Caught in the crossfire, farmers have had to abandon their plantations to drought, disease and destruction, says Yemeni journalist Mohammed al-Hakimi, who has done extensive research on the topic.

“Palm plantations in places like Hodeidah are at risk of extinction as a result of drought and desertification, which is swallowing up areas.”

The full impact of this on the local communities has yet to be properly quantified, but the destruction of crops such as date palms removes a source both of income and food at a time when families like Noha’s are already below the breadline.

Back in the hospital, Noha’s mother has little hope for a brighter future.

“We have no money, no way of getting money and most aid has already dried up,” she says, keeping watch over her little girl.

“I just hope my daughter can survive this.”