When the marine biologist Rachel Carson was a young girl, she discovered a fossilized shell while hiking around her family’s hillside property in Springdale, Pennsylvania. Those who knew her then would later contend that this relic sparked such intense reverie in her that she instantly felt a tug toward the sea. What was this ancient creature, and what was the world it had known?

Though Carson had never seen the sea herself, she threw herself into its study. She studied biology, then zoology, eventually taking a job as a writer for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. All of this was incredibly rare for a young woman in the 1920s and ’30s, but Carson’s trajectory was a demonstration of the expansive potential of curiosity. It also reflected the tireless tutelage of her mother, Maria, who had instilled a love of the wild in her children by regularly taking them on walks to learn about botany and birds. Carson absorbed these lessons and, throughout her life, maintained a deep conviction that wonder had to be at the foundation of any relationship with nature.

In her final months, Carson, age 56, sickened from cancer treatments and in constant pain, still had a couple of remaining projects in mind. One of these was what she called the “wonder book.” By that point, Carson had already written four best-selling books, most famously Silent Spring, which documented the dangers of pesticides, including DDT, and is now widely credited with catalyzing the modern environmental movement. Yet Carson felt she had one more thing to say. The “wonder book”—published posthumously as The Sense of Wonder—was based on a lyrical essay about the importance of cultivating wonder in children. Perhaps because of her early experience, Carson placed great faith in this emotional response that, once found, could serve as “an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantments of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things that are artificial.” Wonder led to a sense of the beautiful, which led to the pursuit of knowledge about the object that triggered the feeling in the first place. Children possessed this “clear-eyed vision” innately, but it had to be kept alive. Adults could awaken this quality in themselves too. With enough attention, she argued, anyone could “feel the rain on [their] face and think of its long journey, its many transmutations, from sea to air to earth.”

[Read: Swimming in the wild will change you]

Why did Carson feel so strongly the need to proselytize the wonders of wonder? Perhaps she sensed that, without it, an emotional connection with nature would be impossible; without it, the environmental movement had no hope. “The more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe,” she once said, “the less taste we shall have for the destruction of our race.” Today, we remember Carson for her crusading spirit and moral clarity; we cite Silent Spring as an example of a political book that spurred public outrage and prodded the government toward action. However, we far less frequently remember Carson for this other thing she spent her whole life doing: helping the public cultivate a sense of awe about nature. To see this facet of her sensibility most clearly, we need to return to her first three books—The Sea Trilogy.

It was April 1936. Dust storms thundered across the plains of Texas and Oklahoma, Nazi Germany had reoccupied the Rhineland a month earlier, and the Spanish Civil War would soon erupt. Meanwhile, in Washington, D.C., Carson had just turned in a draft of her latest essay, titled “The World of Waters.” Her assignment at the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries had been to write an introduction for a government brochure on fish. The year before, she had helped write a radio series informally dubbed “seven-minute fish tales,” a deceptively difficult job that had confounded other employees who either knew hard science or knew how to write but couldn’t merge the two. Rachel Carson, it turned out, could. As her supervisor, Elmer Higgins, read the draft, Carson sat quietly in his cramped office and nervously awaited his verdict. “I don’t think it will do,” she later recalled him saying when he looked up again, with a “twinkle in his eye.” These pages were not suitable for a government brochure on fish, he continued. No. This was literature. He passed the pages back to her and said, “Better try again. But send this one to The Atlantic.”

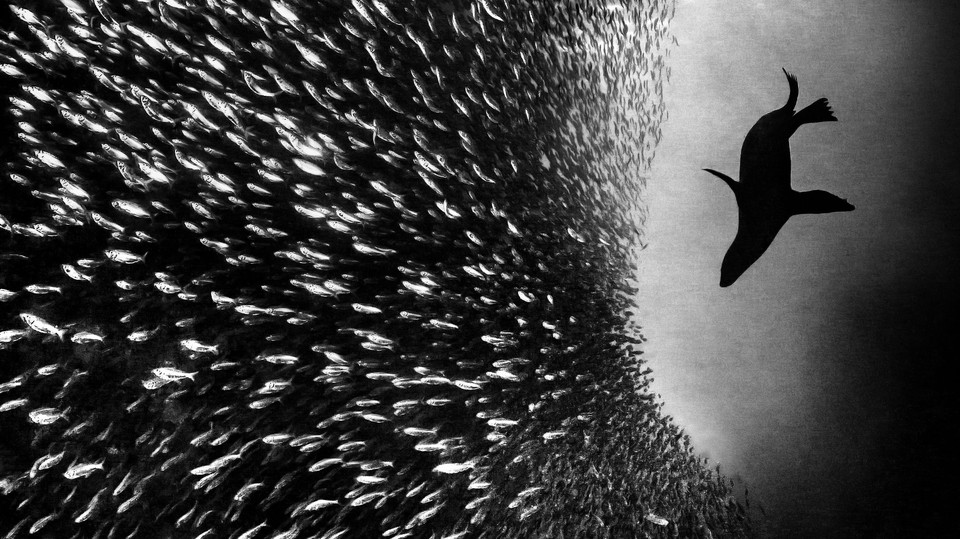

A version of that essay was published in this magazine a year later, titled “Undersea.” The editor who accepted Carson’s essay praised it for illuminating science “in such a way as to fire the imagination of the layman.” Lively, lyrical, and exactingly researched, the essay showcased what would soon be recognized as her signature style to a national audience. Here was her abiding emphasis on ecology and life cycles—and her commitment to making the reader feel something. She strove to educate, and to astonish. She deftly manipulated sound, rhythm, and atmosphere. Life on the ocean floor was described as in a moody noir, bathed in perpetual “bluish twilight” where “swarms of diminutive fish twinkle through the dusk like a silver rain of meteors, and eels lie in wait among the rocks.” The mid-ocean lulled with its “lilt of the long, slow swells,” while at the shore, the aptly accented “foam and surge of the tide” beat relentlessly upon its sturdy little inhabitants. Determined to avoid what she later called the “human bias” of popular science writing, Carson sought to portray the world of waters solely from a creaturely perspective, urging readers to “shed [their] human perceptions.”

By Carson’s own estimation, from the publication of “Undersea,” “everything else followed.” Her career as a poet of the sea unfurled. Carson went on to write three best-selling books about the sea: Under the Sea-Wind (1941), adapted from “Undersea”; The Sea Around Us (1951); and The Edge of the Sea (1955). These three books make up her Sea Trilogy, recently reissued by Library of America. Under the Sea-Wind was, Carson thought, her “first real act of literary creation.” It stands out in her body of work for its genre-breaking creative daring—reading more like an adventure novel than a book of science. Written from a close-third-person omniscient point of view, interweaving the perspectives of different (named) animal characters, it animates the life stories of Rynchops the skimmer, the sanderling couple Blackfoot and Silverbar, and Anguilla the eel. We see them struggling to survive, making a life, battling harsh weather, feeding, fleeing, and embarking upon their final journeys to mate and then die. Today we are familiar with the high-definition, IMAX version of what Carson conjured through language—the swoops of riveting pursuit and slow-motion escapes of the nature documentary. That she honed her storytelling chops while writing the public-service equivalent of bingeable TV is unsurprising. About 80 years later, Sea-Wind still reads like a scintillating adventure tale. Reviews from scientists and nonscientists alike praised it for its “lyrical beauty” and “faultless science,” “so skillfully written as to read like fiction.”

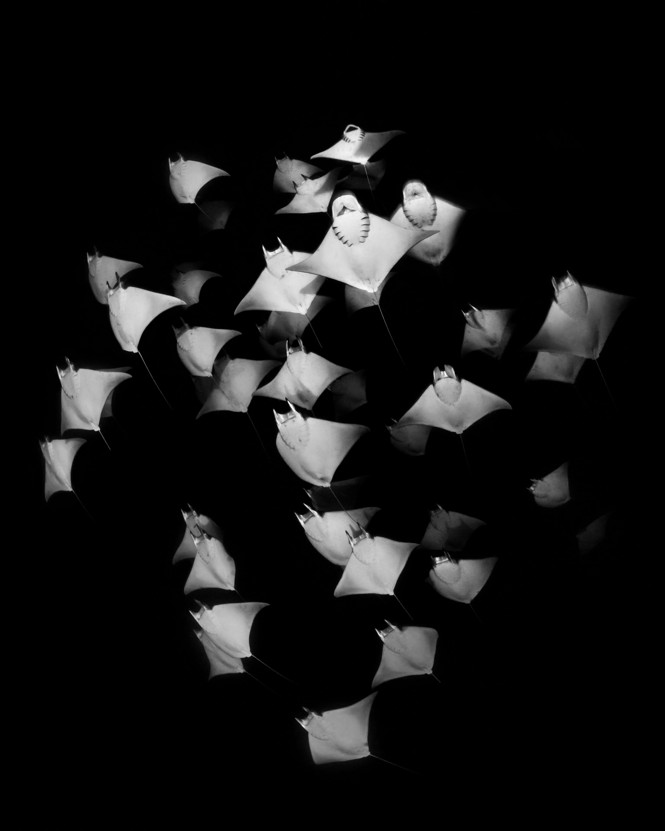

Carson wanted not just to entertain but also to impart an abiding sense of interconnectedness. In a section of Sea-Wind about the reawakening of life on spring seas (yes, seas have seasons too, I learned), Carson pulls us in to witness the great seasonal mackerel spawn, a “sprawling river of life, the sea’s counterpart of the river of stars that flows through the sky at the Milky Way.” There, we are introduced to one mackerel, whom Carson cheekily names “Scomber.” (Scomber is a genus of fish, known as one of the “true mackerels.”) We see Scomber’s conception, his development from an egg floating passively on the sea, his formation of a backbone. Alone, he must evade the hungry mouths of anchovies who are themselves hunted by larger bluefish. Crossing the murky depths, he’s soon caught in the grasp of a “shimmering oval globe”—the comb jelly Pleurobrachia. But before he’s sucked into its pulsing mouth—nail-biting tension here!—the comb jelly and Scomber are both unexpectedly trapped in the mouth of a sea trout, who fortunately spits them both out after a few experimental bites.

The sequence is thrilling, while showing in immersive detail the workings of one food chain among innumerable others in the ocean. Though there is little sentimentality here about the death of any particular creature—everything, whether plankton or fish or mollusk, is always eating or being eaten—there is a sense of horror at human plunder. The sheer scale of what humans took for themselves is what made them monstrous. Carson opts to portray the ravage of resources indirectly, through mood and insinuation. We zoom in—something is amiss. Coming over the plateau, Scomber and his companions see some large haddock caught, “turning and twisting slowly on the hooks that they had swallowed.” Narrowly evading this gruesome scene, the mackerel then confront another threat looming from below: a trawl net, a “cavernous bag” scooping up thousands of pounds of life from the ocean floor.

[Read: Netflix’s Our Planet says what other nature series have omitted]

After spending all of Scomber’s life with him, how could the reader not feel for him, root for him? Narrating from the point of view of animal protagonists is a classic technique that builds empathy bridges, but in this case it’s done without the purely commercial manipulations of, say, Disney movies. Instead, a different political agenda is at work. The violence inherent in extractive capitalism and the particular logic that allows for some lives to be rendered utterly dispensable is intimated rather than stated. Can Scomber persist? At the end of the mackerel chapter, Carson floats away from the besieged mackerel’s mind and into the mind of a young fisherman on the deck of a boat, who’s been at sea for only two years:

He sometimes thought about fish as he looked at them on deck or being iced down in the hold. What had the eyes of the mackerel seen? Things he’d never see; places he’d never go. He seldom put it into words, but it seemed to him incongruous that a creature that had made a go of life in the sea, that had run the gauntlet of all the relentless enemies that he knew roved through that dimness his eyes could not penetrate, should at last come to death on the deck of a mackerel seiner, slimy with fish gurry and slippery with scales.

What had the eyes of the mackerel seen? How was it that this mackerel, who had “run the gauntlet” of the sea, should end life in this ignoble way? The young fisherman is confronting these ecological questions firsthand, asking the questions that Carson would like us to ask. And now that we’ve experienced what the mackerel saw and the fisherman wondered—what follows?

If Carson’s sea books can serve a “utilitarian” purpose today, guesses Sandra Steingraber, an environmental activist and the editor of the new Sea Trilogy edition, they mark a “disappearing natural baseline” that describes “how the all-creating ocean functioned, how its creatures lived and interacted.” As I read, I noted, sadly, all the past-tense verbs in that sentence. Is it already too late to know the sea as Carson once did? In her introduction, Steingraber goes on to list the currently unfolding catastrophes that Carson never lived to see: “industrial overfishing, or news of the potential collapse of the Gulf Stream, or massive floating garbage patches, or icebergs the size of states breaking off Antarctica, or micro-plastics replacing plankton in the water column, or plans for deep-sea mining.” To that list one might add ocean acidification, hypoxic dead zones, sonar testing, and coral die-off. Steingraber strains for some silver lining: “But her words fortify us for battles” and—she sums things up waveringly—“inspire curiosity and care about what we are in the process of losing.”

Is wonder still possible, given our climate crisis? Wonder implies some degree of leisure and time; it requires slow, sustained, and contemplative attention—a luxury that, perhaps, we can no longer afford. Even Carson, when she wrote the new preface for the revised 1961 edition of The Sea Around Us, couldn’t help but inject an urgent warning about the practice of dumping nuclear waste into the ocean. She called the previous assurance that the sea was so large as to be inviolate a “naive” belief. Today, as dire emergencies unfold, rationalizing time spent merely appreciating the natural world seems even more difficult. During the COP26 climate conference, protesters held up signs spelling doom and chanted: “If not now, when? When?” Greta Thunberg summarily declared the conference a failure, dismissing it as a meaningless PR event for “beautiful speeches.”

[Read: The dark side of the houseplant boom]

The climate crisis requires urgency on a global scale: Countries need to act, policies need to be set in motion. But slowness is needed as well. As the writer Naomi Klein points out in On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New Deal, our “culture of the perpetual present” is not equipped to deal with the generations-long nature of the crisis. Market forces compel us to speed up precisely when we need to take a beat; to insulate ourselves from the physical environment precisely when we need to develop a more intimate connection. Modern life guarantees the atrophy of important “observational tools,” Klein writes; rather than stopping someplace to get to know its rhythms and cycles, we sever and uproot ourselves by living through screens and portals. All of this helps maintain the harmful illusion that if one environment gets destroyed, there will always be some other “away” to escape into.

In our day-to-day lives, pure enjoyment of nature can seem somehow suspect or unproductive, and the justification of such time spent is often couched in utilitarian or economic terms. Walks are for clearing heads; hikes are good exercise. Carson anticipated this line of thinking. In The Sense of Wonder, she asks rhetorically, “What is the value of preserving and strengthening this sense of awe and wonder … ? Is [it] just a pleasant way to pass the golden hours of childhood, or is there something deeper?” Though we tend to think of the American mid-century as a time of prosperity and advancement—perhaps they had time to wonder, but we don’t—it was, in fact, equally plagued with existential emergencies: the Cold War, McCarthyism, segregation and intractable racism. Stopping to wonder seemed frivolous back then too. Carson’s rebuttal, rousing and powerful, argues that wonder provides no less than joy, hope, and inner strength in the face of despair and annihilation:

Those who dwell … among the beauties and mysteries of the earth are never alone or weary of life. Whatever the vexations or concerns of their personal lives, their thoughts can find paths that lead to inner contentment and to renewed excitement in living. Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts. There is symbolic as well as actual beauty in the migration of the birds, the ebb and flow of the tides, the folded bud ready for the spring. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature—the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after the winter.

Trusting in wonder’s resonant effects is something akin to faith. Fear can be motivating, but so can love. Taking a cue from Carson, I’ve been trying to take more walks with open eyes and an open heart, unpracticed as I may be. I treat myself like a child and go around with a pair of binoculars. After reading that the spring migration of birds is again in full swing, one night during a full-ish moon, I took my binoculars and sat out on the stoop. One of the fun activities that Carson recommends is to point the lens to the moon to see if you can catch the silhouettes of migrating birds as they pass across its shining face. I also listened hard to detect the “wisps of sound,” the “sharp chirps, sibilant lisps, and call notes” of eager flocks. Instead, I heard trucks clattering down I-95 and my neighbor wheeling his garbage out. After about half an hour, I brushed off my pants and headed back inside. It hadn’t been a spectacular experience by any means, but, maybe because I had strained so long to hear them and see them, I dreamed of the birds that night. In my mind’s eye, an endless, exuberant procession of birds passed high above the sleeping city, dipping in and out of the moonlit clouds, calling to one another from darkness to darkness. They were sure of their destination, unwavering.